Capturing the Light of the Nile, Egypt's First Photographs

- Arts

- History

Written by Jeff Koehler

“To copy the millions of hieroglyphs that cover even the exterior of the great monuments of Thebes, Memphis, Karnak, and others would require decades of time and legions of draftsmen…. By daguerreotype, one person would suffice.”

—François Arago, January 7, 1839, during his announcement in Paris of the invention of photography by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre

Speaking as an astronomer, physicist, member of parliament and secretary of the Académie des Sciences, François Arago’s words resonated throughout the land. Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt had ignited a national passion for all things pharaonic when, from 1798 to 1801, he brought not only occupying soldiers but also more than 150 savants—scholars, cartographers, artists, naturalists, draftsmen and even a musicologist—who recorded the details of ancient sites and modern customs. The result was the mammoth Description de l’Égypte, published between 1809 and 1829 in some two dozen volumes with around 900 plates of engravings. It revealed an Egypt full of more wonders than ever had been imagined, and it left its readers clamoring for more.

Arago even lamented that photography had not yet been invented during Napoleon’s time in Egypt. “Everyone will imagine the extraordinary advantages which could have been derived from so exact and rapid a means of reproduction during the expedition to Egypt,” he told the Académie.

There was little visual record beyond etchings, watercolors, drawings and oil paintings. And no objective record. These were artists’ renderings, observed us scholar Andrew Szegedy-Maszak. “No matter how accurate, paintings, drawings, and prints are always acknowledged as interpretations shaped by the artist’s hand and eye. A photograph, on the other hand, was initially thought to offer a direct, unmediated slice of reality,” he wrote in Antiquity & Photography: Early Views of Ancient Mediterranean Sites. At the time, Daguerre’s invention wasn’t regarded as a process by which humans reproduced nature, but rather one by which nature reproduced itself, quickly and objectively.

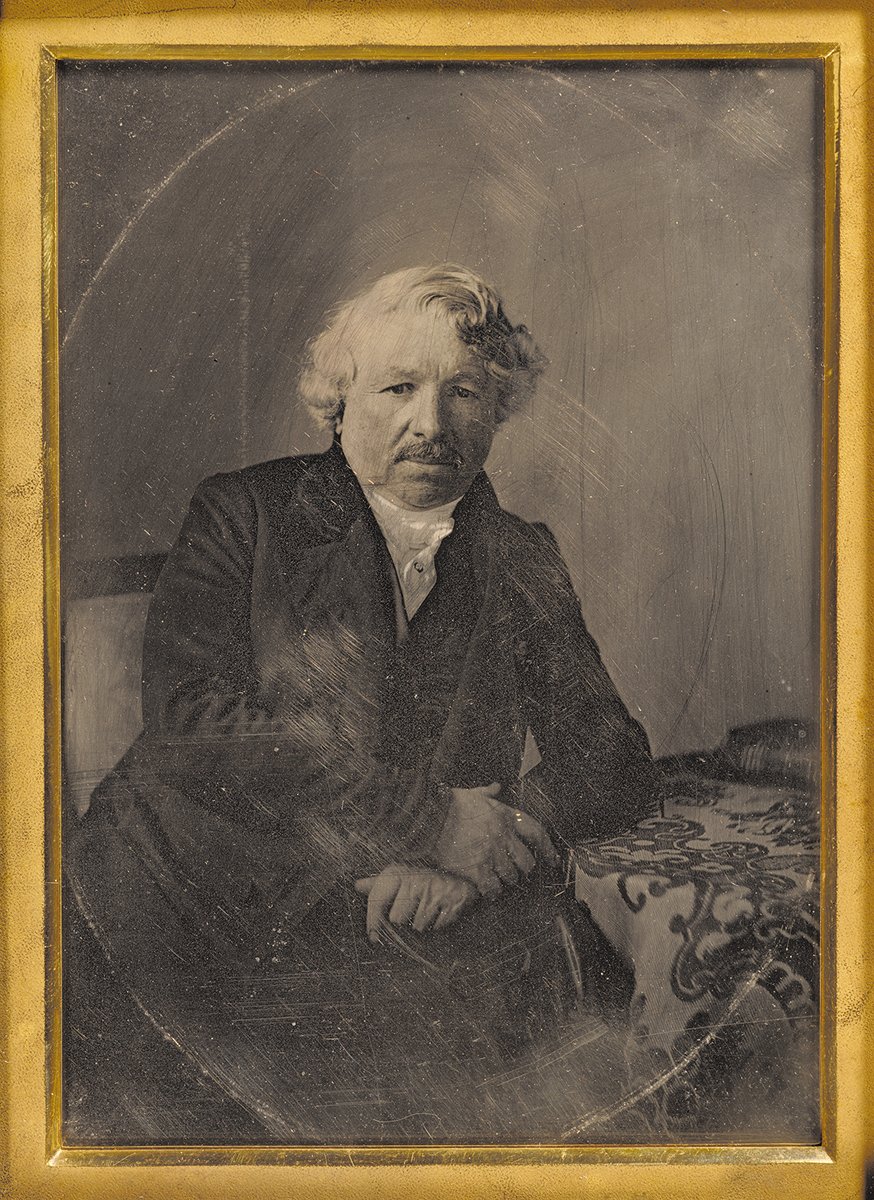

Daguerre was a painter and stage designer who had created the diorama, a theater of illusion without actors that employed large painted scenes and clever lighting. But his obsession was to capture and fix an image using mechanical means.

Battling his own lack of scientific training, he spent years compulsively experimenting alone, to the point that his wife feared for his sanity. “He has for some time been possessed by the idea that he can fix the images of the camera,” she told a Parisian pharmacist. “He is always at the thought, he cannot sleep at night for it…. I am afraid he is out of his mind. Do you, as a man of science, think it can be done, or is he mad?”

In 1826, Daguerre learned from an optician that another amateur scientist, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, was conducting his own secretive investigations into a light-capturing process he called “heliography.” Daguerre immediately wrote to him, and they met a year later. At first, Niépce was reluctant to divulge details of his work, but at the end of 1829, they formed a partnership.

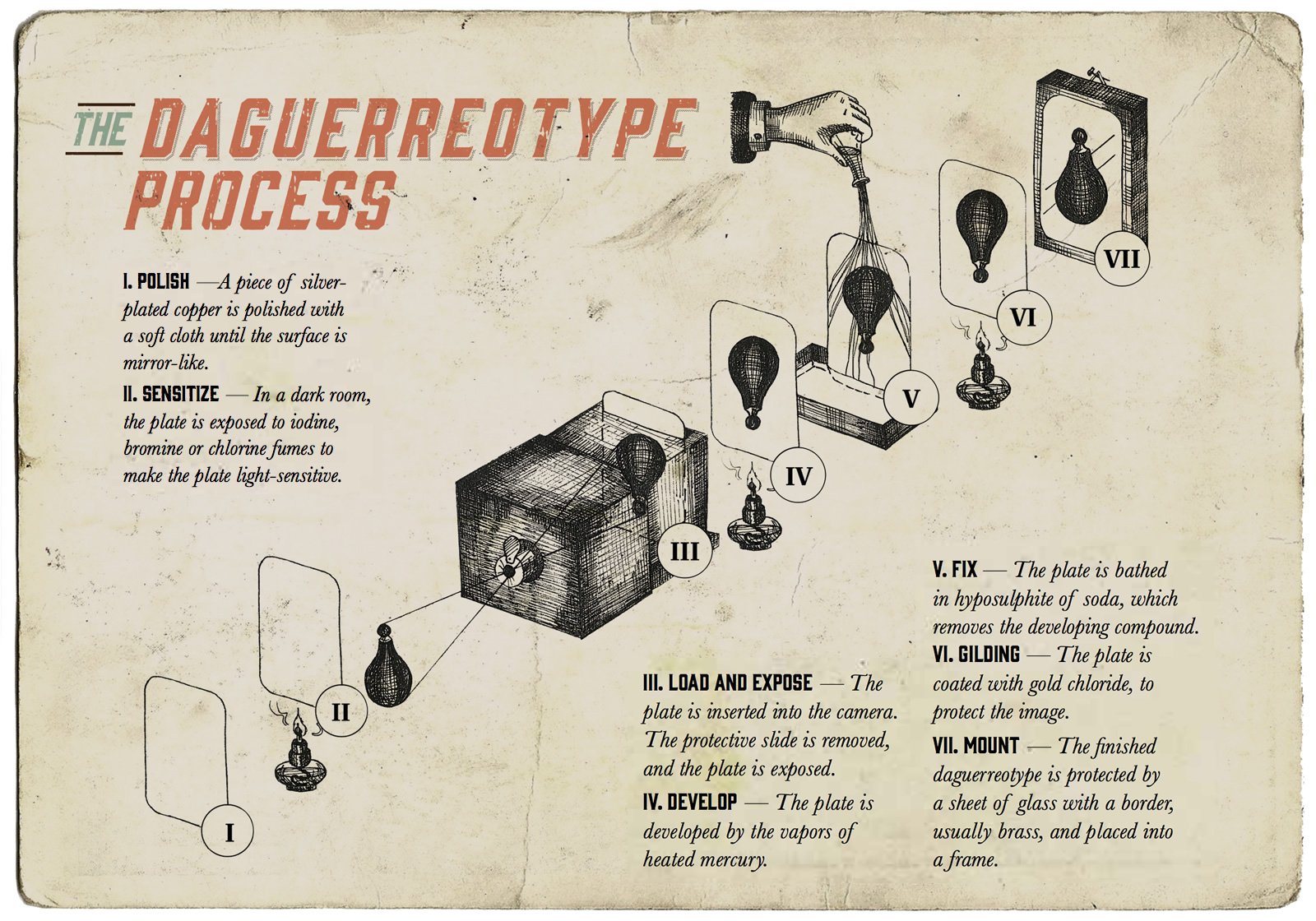

When Niépce died suddenly in 1833, his son took over the partnership. Daguerre carried on experimenting until, in 1837, he managed to capture an image by sensitizing a silver-coated copper plate with the fumes of iodine, placing it in a wooden box camera, exposing it to the light and then developing it in mercury fumes. He claimed he happened upon this idea when he accidentally left a spoon on an iodized plate onto which light was striking: When he picked up the spoon later, he saw a perfect shadow of it on the plate.

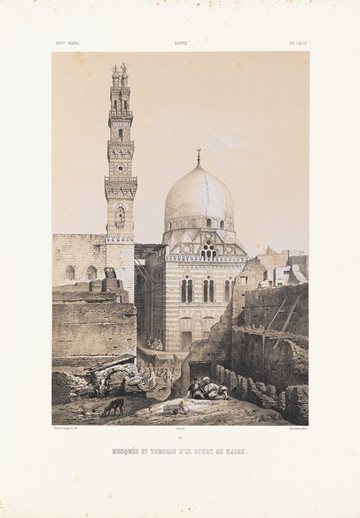

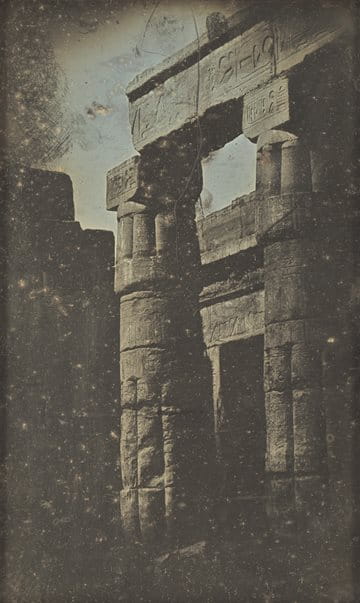

Coming to Egypt two years after Vernet and Goupil-Fesquet, Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey spent several years making more than 800 daguerreotypes of monuments throughout the eastern Mediterranean. Some, such as his view of the Sultan Qansuh al-Ghuri madrassah and mosque in Cairo, above, were published as lithographs; many of his other plates, however, lay forgotten until the 1920s and became publicly known only recently, including a daguerreotype of the pillars of the mortuary temple of Seti below.

Although the daguerreotype did not reproduce colors, it produced an image with rich tonal gradations that gave it almost a 3-D feel. It was a one-shot process that produced a positive image—in the manner of a modern Polaroid—on a highly reflective, polished surface. Daguerre showed the results of his work to the telegraph inventor Samuel Morse, who was awestruck at the fine detail.

“[The images] are produced on a metallic surface, the principal pieces about 7 inches by 5, and they resemble aquatint engravings, for they are in simple chiaroscuro, not in colors. But the exquisite minuteness of the delineation cannot be conceived. No painting or engraving ever approached it,” Morse wrote to his brother, who published the letter in The Observer, the New York newspaper he edited.

Daguerre found a steadfast champion of his invention in Arago, one of France’s most respected scientists. Arago not only understood the implications of Daguerre’s invention but was also well placed to promote it. He saw its potential to be an important part of French intellectual life and lobbied the government to buy the invention outright and make it freely available.

“France should nobly give to the whole world a discovery that could contribute so much to the arts and sciences,” which would demonstrate France’s supremacy in these fields, he told the Académie.

On August 1, 1839, under a bill passed by the chambers of deputies and signed by King Louis-Philippe, the French government purchased Daguerre’s invention, patent and all details regarding it. In return, Daguerre and Isidore Niépce, his late partner’s son, received pensions. The government gave Daguerre just three weeks to draw up a plan for manufacturing the daguerreotype and to prepare an instruction booklet before making the process public. Daguerre quickly made an agreement with his brother-in-law Alphonse Giroux, whose family business made furniture and cabinets, to produce a slightly improved, commercial version of the apparatus.

The mystery and suspense around the method had been building since January. On August 19, at a joint session of the Académie des Sciences and the Académie des Beaux-Arts packed with some 200 spectators and several hundred more who stood outside, Daguerre’s photographic process got its first public showing.

Daguerre was a born showman, but perhaps a case of nerves at the prospect of explaining the science behind his invention to a room full of scientists prompted him to let Arago make the historic presentation.

The British magazine The Spectator had reported a few months earlier that the invention was “more like some marvel of a fairy tale or delusion of necromancy than a practical reality.” Now the public saw that simply “making light produce permanent pictures” was not fantasy, reported a German attendee. “The crowd was like an electric battery, sending out a stream of sparks,” he noted. “A few days later, you could see in all the squares of Paris three-legged dark boxes planted in front of churches and palaces.”

The first models of the Giroux daguerreotype camera were ready for sale by the August deadline, and an advertisement for it appeared in the La Gazette de France on August 21. The price: 400 French francs—an average worker’s annual salary.

The kit consisted of a wooden box measuring 30 x 38 x 51 centimeters, with a brass lens mount. At the rear, a box where a ground glass viewing plate would be slid in to allow composition and focus could be switched out for a holder with the prepared, light-sensitive plate. It came with other boxes to hold the chemicals for sensitizing plates and developing the images. Within weeks, the 79-page instruction manual had been translated into both English and German.

Daguerreotypists raced to capture the world’s wonders with their new medium. Egypt was among their first and most desired destinations—along with Greece and Rome—but Arago’s lofty goal of photographing all of the country’s hieroglyphics remained a scholar’s wish amid newly fervent commercial competition.

Aiming to be the first to collect and publish images of the world’s great monuments, the wealthy Parisian optician Noël-Marie Paymal Lerebours equipped a handful of amateurs with cameras and chemicals.

In addition, he offered a commission to the Orientalist painter Horace Vernet, director the French Academy in Rome, and his nephew Frédéric Goupil-Fesquet—the latter to make photographs to complement his uncle’s sketches. The two traveled to Marseille and departed for Egypt on October 21, 1839. They stopped in Italy, Malta and Greece before landing in Alexandria on November 4.

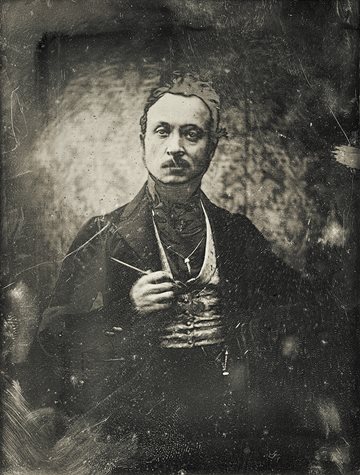

Two days later, the French consul presented the pair to the pasha, Mohammed Ali, an Albanian who had become Egypt’s de facto ruler after the French withdrawal. Mohammed Ali was “lying on his divan in the corner of the living room,” Goupil-Fesquet wrote in 1844 in Voyage d’Horace Vernet en Orient. He questioned his guests on the state of the arts and sciences in Europe and expressed an interest in seeing how the new photographic instrument worked. Vernet and Goupil-Fesquet returned to Ras el-Tin palace on the edge of Alexandria’s harbor the next day at seven a.m. to demonstrate the daguerreotype.

The operation lasted some minutes, and Mohammed Ali was wary. After being exposed, the sensitized, polished mirror was fumed with mercury in a wooden box. The fixed image was then bathed in a solution of hyposulphite of soda and rinsed in distilled water. Although it was a mechanical process that applied science to the arts, it had a whiff of magic about it.

That image from November 7, 1839, is the first documented photograph of Egypt, and indeed of the African continent. The original plate is long gone, but an engraving from it (see top-most banner image) shows an ornate outer gate with two men, perhaps a guard and a doorman, lounging in the open doorway. Behind, with tall windows and low-peaked roofs, stands the palace harem. A couple of trees lean over the fence.

Like the crowd in Paris, Mohammed Ali was awestruck. “His Highness gave way to the increasing sense of wonder and amazement,” wrote Goupil-Fesquet. “‘It is the work of the devil!’ he cried out.”

Nevertheless, Mohammed Ali soon embraced the camera enough to pose for it: a plump, white-bearded ruler with a broad sash, bejeweled belt and an apprehensive expression. According to Goupil-Fesquet, Mohammed Ali even learned to use the camera.

Egypt, it turned out, was an excellent place to work as a daguerreotypist, especially in the cool of winter. It offered photographers good and ample light, which was important for the long exposures daguerreotypes required. Most importantly, it had an abundance of historical places of the highest public interest to capture. Other photographers were not long

in arriving.

That November, Vernet and Goupil-Fesquet met another daguerreotypist in Alexandria, Pierre Joly de Lotbinière. Born in Switzerland, raised in France and, at age 41, a wealthy landowner living outside Quebec, Canada, he was in Paris at the time of Daguerre’s announcement. He was about to embark on a tour of the eastern Mediterranean, and he was fascinated by the new photographic process. Caught up in “daugerreotypomania,” he, too, had secured a commission (as well as equipment) from Lerebours. En route to Egypt, Joly de Lotbinière had stopped in Athens, where in mid-October he had made the first photographs of the Acropolis.

Soon after meeting, the three daguerreotypists made their way south to the splendors of Cairo. “We have been daguerreotyping like lions,” Vernet wrote to a friend. The trio arrived in neighboring Giza to photograph the Sphinx on the same November day. There were just two cameras in all of Egypt, and the photographer behind each was jockeying for the best angle of the same famously enigmatic antiquity.

On November 20, Goupil-Fesquet captured another iconic monument, the Pyramid of Cheops, working from outside a gate that surrounded the complex. The scene, which is known today only through a subsequent engraving (see top banner image), is bucolic, with a saddled camel and three people quietly lounging in the foreground, the pyramid rising behind it in brilliant light. The exposure took 15 minutes.

While Vernet and his nephew began their journey back to Europe soon after that, Joly de Lotbinière traveled up the Nile to photograph landmarks like the temple of Karnak, the Colossi of Memnon, the palace of Medinat Habu and other sites around Thebes, as well as the temples at Kom Ombo, Philae and Abu Simbel. His view of the last shows the 1200 bce monument to Ramses ii buried partially in sand.

Joly de Lotbinière wrote in his diary that he made 92 images on his trip back to France, via Jaffa, Jerusalem, Damascus and Lebanon. By modern standards, that is few for such an extensive journey, but the process to capture a daguerreotype, especially “in the field,” was laborious and demanding.

Daguerreotypists had to carry more than 50 kilograms of equipment, including the camera, plates, a developing box, bottles of chemicals, dishes for mixing, buffs for polishing and a heavy wooden tripod. Taking daguerreotypes was full of disappointments and failures. Plates would not always develop well or at all, due to mistakes on the part of the photographer, extreme heat that changed or neutralized the effects of the chemicals, lack of sufficiently clean water, even insects. Once finished, a plate was highly susceptible to scratches and to deterioration in light: It had to be stored in a velvet-lined case. Today, none of the original plates from either Joly de Lotbinière or Vernet and Goupil-Fesquet survive, and we see their work only through engravings based on them.

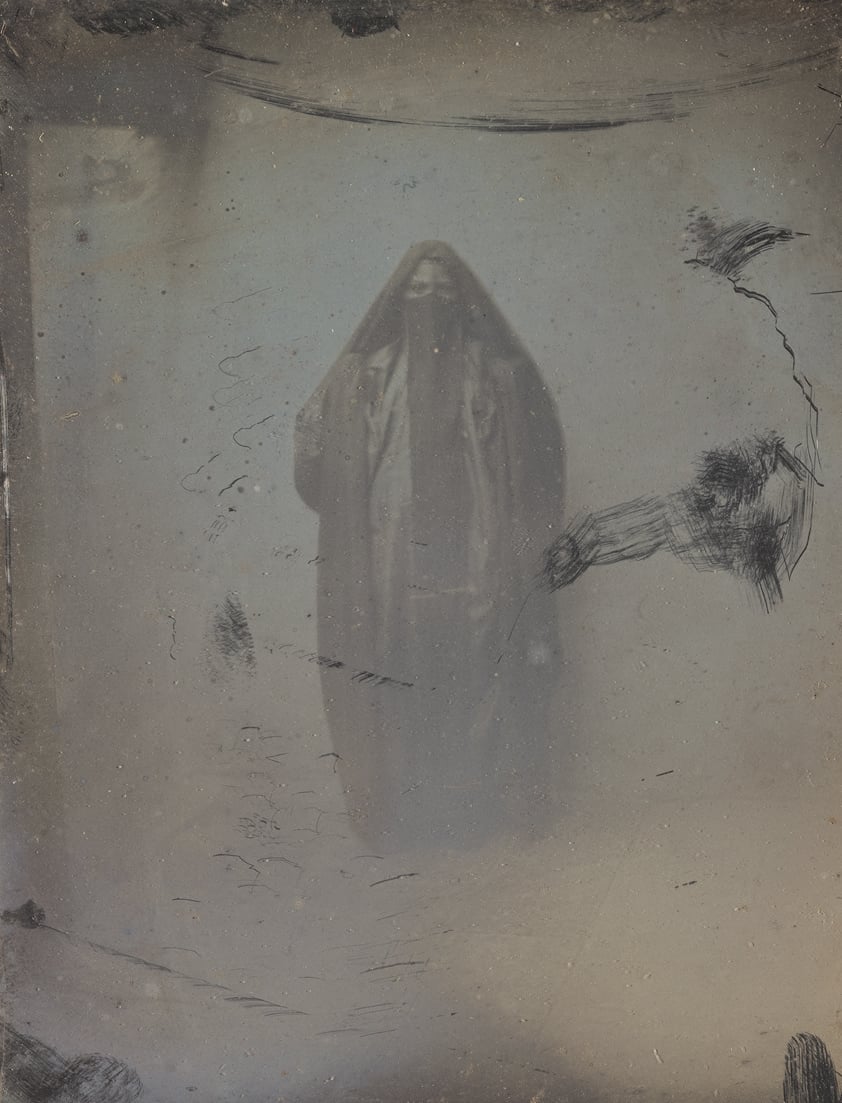

Because daguerreotypes were positive images on metal, they could not themselves be reproduced. The pictures had to be hand-copied by artists onto copper plates or engraved onto separate printing plates. Sometimes lines were engraved directly onto the daguerreotype plates.

A handful of images of the travels of Vernet, Goupil-Fesquet and Joly de Lotbinière were published in 1840 and 1841, first in Lerebours’ Excursions daguerrienness: vues et monuments les plus remarquables de globe. Joly de Lotbinière’s images of ancient ruins also appeared in Héctor Horeau’s Panorama d’Égypte et de Nubie (1841).

The medium as a profession or considered as an art form remained in the future. These pioneering travel photographers were enthusiastic amateurs. Vernet and his nephew fulfilled their commission, but they were “primarily interested in gathering authentic raw material for their own paintings and etching,” noted journalist and historian of modern Egypt Max Rodenbeck. There is no record of Joly de Lotbinière taking another photo after he returned to Quebec.

While the daguerreotype’s importance was destined to remain in the history books, its role as the photographic medium of choice in Egypt was short-lived. By 1845, a new process that used calotype paper negatives, which could reproduce further images directly from the original, had already begun to replace it.

For the Egyptian traveler, paper negatives also were lighter and less bulky than the copper plates, and they could be sensitized weeks in advance. While daguerreotypes offered crisp and practically grainless images, the calotype paper negatives absorbed the light-sensitive chemicals and thus lacked the fine details of their predecessor. They looked like monochromatic watercolors in tawny oranges, sepia browns and grays. Yet today it seems that this made the process ideal for Egyptian subjects. The negatives’ paper fibers evoke the textured surfaces of stones and desert, giving a tactile quality to the image, and the overexposed, sulfuric sky lent a feeling of the heat—all without sacrificing the objectivity of a photographic image. Their name was fitting: Calotypes came from kalos, Greek for “beautiful.”

In his original announcement, Arago had pled for the daguerreotype in the service of science. But once the early practitioners had their tripods steadied on Egyptian soil, they seemed to have little interest in merely recording hieroglyphics. Instead, they captured the grandiosity and magnificence of the most famous monuments—and in doing so, they also captured the beauty of the region.

The technology continued to improve and diversify, and the paper negatives were soon superseded by glass ones in the wet-collodion process that combined the sharpness of daguerreotypes with the reproducibility of calotypes. In 1889, 50 years after Daguerre’s invention, a New York company owned by George Eastman marketed the first commercial, transparent roll film and the camera named Kodak No. 1, making photography accessible to the general public.

Ever since then, a camera has been an important traveling companion. “One of photography’s most exalted and dependable functions over the last 150 years has been to supply reports on the look and life of far-off lands,” wrote New York Times critic Andy Grunberg. Beginning with the Pyramids, “pictures have served as our first introduction to the splendid and the exotic.”

The early daguerreotypists enlarged the public’s sense of the world by offering the first mechanically objective images of Egypt’s unique patrimony. They captured the moment when its monuments and murals were beginning to offer modern clues about millennia of culture. They spurred interest in the region and, with it, mass tourism. They stimulated the desire to go and see for oneself—and to capture it with a camera.

You may also be interested in...

The Heart-Moving Sound of Zanzibar

Arts

Like Zanzibar itself, the ensemble style of music known as taarab brings together a blend of African, Arabic, Indian and European elements. Yet it stands on its own as a distinctive art form—for over a century, it has served as the island’s signature sound.

On the resilience of handicrafts in Bosnia-Herzegovina

Arts

The backstreets of Sarajevo’s old town are alive with the repetitive thud of metalworking. In this European capital, with its contemporary high-rise buildings and modern brands, you can still hear the heartbeat of tradition.

Nakshi Kantha: Tradition and Identity in Every Stitch

Arts

History

A traditional form of quilting in Bangladesh in which women embroider family history, love and memory into the fabric is blanketing markets locally and beyond.