Via Egnatia to Rome and Byzantium

- History

Written by Louis Werner

Photography and video by Matthieu Paley

Interactive Timeline

KM1

The way abruptly leaves the Shkumbin River at Mirakë village, and its first switchback comes just before the Ottoman-built crossing known in Albania as Ura e Kamares, or Bridge of Niches. It quickly gains some 300 meters over the valley floor, here subject to frequent washouts and thus the reason for its higher route, before settling onto a steady contour line heading almost due east.

Shepherds and mule-driving woodcutters pass frequently in these mountains, and their animals’ hooves clatter on smooth stones, polished and almost gleaming from long use. It is a joy to hike these best-preserved kilometers of the path, at times four meters wide and still well paved, the path that here they call Rruga Egnatia, which is Albanian for Egnatia Road.

Two thousand years ago, just as today, the shortest distance between Rome and the Bosporus was a straight line, mostly over land. From Brindisi near the southeast tip of Italy’s bootheel, that line crossed the Adriatic Sea’s Strait of Otranto to the Albanian shore. From there it passed through the mountains of ancient Illyria, Macedonia and Thrace to arrive, more than 1,100 kilometers later, in Byzantium, as Constantinople was called before Roman Emperor Constantine gave it his name in the fourth century ce, and before it became Istanbul in 1930.

This line is traced by two of Rome’s most famous roads: the Via Appia, from Rome south through Italy, and the Via Egnatia, east through the Balkans to Istanbul. If the Via Egnatia was the Roman Empire’s main route east, in use long after the empire fell, it gained new life under the Ottomans—even before their 1453 conquest of Constantinople—who reversed traffic and made it one of their primary corridors west, especially during the Balkan conquests of the late 14th century. As a result, today many mosques, markets, charitable kitchens (imarets), caravansarais (hans) and baths (hammams) along the route date from this time, when in Turkish it was known as Rumeli Sol Kol, literally “Balkan Left Arm.”

Geographers use the word dromocracy or “rule by road”—from the Greek word dromos (by which English gets aerodrome and velodrome)—to describe the Ottoman Empire’s deep reliance on its road system. West of Constantinople, these included the Orta Kol (Middle Arm), northwest to Belgrade, and Sağ Kol (Right Arm), north to Ukraine. Mehmet the Conqueror, upon leaving Constantinople with his army toward the Balkans, was once asked where he planned to lead it. His response— “If even a hair of my beard knew this answer, I would pull it out”—indicates not only the secrecy of his mission but also the choices these roads offered.

KM7

The road winds past farmsteads with hay stacks in the yards and rough enclosures for sheep and goats. Mussolini’s repairs during Italy’s occupation of the 1940s make it difficult to discern Roman from Ottoman from Italian stone-setting, but each seems to have learned from its predecessor, and all is of solid workmanship. The steep slopes and their cascading streams, however, mean regular upkeep is required, and where there is none, the road becomes a washed-out, narrow track. The British painter and poet Edward Lear’s diary entry of “frightful paths” and “formidable precipices” written during his trip this way in the summer of 1848, is not far off.

What we know about Via Egnatia begins with Roman records that include tabulae, Latin for route maps; itineraria mutationum, or lists of stations, also called menzilhaneler in Turkish, where drivers could change horses; mansiones, or inns; and civitates, towns. The Ottomans, in addition to the lists of post stations, kept records of arrivals and departures of official couriers in registers known as menzil defterler. Both empires erected stones inscribed with the distance yet to travel among intermediate stops along the way.

One of the most complete records is in the Bordeaux Itinerary, written in the early fourth century by a Christian pilgrim headed to Jerusalem. It records almost 50 stations between the Adriatic and the Evros River on the modern Greek-Turkish border. Similarly, an Ottoman tax register lists 15 stages between Constantinople west to Thessaloniki, a distance of 600 kilometers, and another seven stages, covering 380 kilometers, onward to Elbasan, Albania—now a modest municipality of 125,000 along the Shkumbin River. The post-house book for Keşan, in eastern Thrace—today northwestern Turkey—records 690 official departures for the year 1703, including 131 destined for Thessaloniki but only two as far as Elbasan.

Scholars have been trying to locate the entire, precise route by linking each known mutatio, mansio and civitas ever since the time of the German philologist Gottlieb Lukas Friedrich Tafel, whose 1842 study of the Via Egnatia is still untranslated from its original Latin (and who never bothered to leave Germany for his research). Most recently, a guidebook published by the Netherlands-based Via Egnatia Foundation provides the best guesses available, along with tips for hiking on the best sections of its original pavement, which total less than one percent of the route today and which lie mostly in Albania.

A milestone found in 1974 outside Thessaloniki, dated to the middle of the second century bce, shows an inscription in both Latin and Greek containing the name Gaius Egnatius, the proconsul who is thought to have built the road after the Roman conquest of Macedonia at the Battle of Pydna in 146 bce. (Later milestones were often inscribed in honor of the reigning emperor.)

Connecting one of the region’s oldest livelihoods with one of its newest relics, a shepherd, top, leads his flock to shelter in a concrete bunker built by Italy in World War ii near the village of Babjë, east of Elbasan.

This wedding reception took place in the village of Dardhë.

Thus it is as much history lesson as it is road trip to walk and ride by taxi, bus and car the full 1,120 kilometers of the Via Egnatia, which is more than twice the length of the Via Appia. From the Adriatic coast to Istanbul, the route passes through four modern countries—Albania, Macedonia, Greece and Turkey—and several dozen towns—some in ruins, others still thriving. The road today is considerably less busy than it was in the time of the Roman orator Cicero, who delayed his departure from Thessaloniki for Rome in order to let a multitude of travelers clear from the overcrowded mansios. Yet the quality of its construction and periodic repair is still evident, and lines written by Procopius, chronicler of the reign of the sixth-century ce Byzantine Emperor Justinian, ring true today: “The paving stones are very carefully worked so as to form a smooth and even surface, and they give the appearance not simply of being laid together at the joints, or even of being exactly fitted, but they seem to have actually grown together.”

KM9

Views to the north across the Shkumbin valley take in even higher mountains. Most are tree-stripped due to high local demand for firewood. The road largely keeps to about 700 meters, and it soon passes through Babjë village, where the first motor vehicle can be heard as it climbs the steep flanks on a road far below. Down there is another early Ottoman bridge, named Ura e Golikut. Its unusual, ramp-like shape, with one side higher than the other, resembles the one on the cover of a popular novel by the prolific Albanian writer Ismail Kadare, The Three-Arched Bridge.

Distances on the Via Egnatia were calculated in some cases by Roman miles, each equivalent to .93 modern English miles, or in other cases, often with the Ottomans, by hours of travel. Firmin O’Sullivan, who traveled the route in 1970 by bicycle and wrote The Egnatian Way, estimated that a Roman soldier could have walked the 700-Roman-mile road in 45 days at a comfortable pace or ridden a horse in half that time; a fast courier could have completed the entire trip, including the sail between Albania and Italy and the Via Appia, in three weeks. By contrast, traveling by sea, all the way around the Peloponnese in southern Greece and up or down the western coast of Italy, would have taken, even in the best of seasons, two to three months.

Today, few names of places or features accord with those of earlier times, as might be expected in a part of the world where much linguistic, religious and imperial change has occurred since Greeks first colonized the region. It is not surprising that the Via Egnatia’s western terminus has changed its name from its original Greek of Epidamnos, a colony of Corcyra (modern Corfu), to Dyrrachium in Latin, to Dıraç in Turkish, to Durazzo in Italian and finally to the Durrës of today.

The beachfront in Durrës seems to belong, or perhaps aspire, more to the Italian Riviera than to the rough uplands of the Albanian interior, but a Roman amphitheater, a Venetian tower, a Byzantine forum, an Ottoman mosque, an Italian colonial culture palace and a wall plaque commemorating a communist uprising against the fascist army of World War ii all attest to Durrës’s checkered history. The facelift given the city by the native-born fifth-century Emperor Anastasius seems not to have lasted: Just beyond the seaside espresso bars and börek bakeries, Durrës turns a bit scruffy. The 17th-century Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi, who was clearly underwhelmed during his visit, noted the lack of bazaars, hans, gardens and vineyards or even a bathhouse. “In brief,” he wrote, “it is a noteworthy tax farm, but not a very flourishing town.”

Farther inland, some things cause other surprises. Says Lorenc Bejko, a professor of archeology at Tirana University who has written on the Albanian reach of the Via Egnatia, “Despite what might look like the provincialism of our mountain culture, in fact our mountain people are as world-wise as those on the coast.” When you walk on the Via Egnatia from village to village, he explains, they may well ask, “Are you headed to Istanbul?”

Between the mountains of Albania and Macedonia, the road skirts the placid northern shore of Lake Ohrid, whose circumference, noted the geographer al-Idrisi in the 12th century, was about three days' walking.

As Evliya wrote about the mountain people, “All the young men go about armed because—God help us—this is Albania and no nonsense about it. They swear only by their shpatë, their sword. Those who are not soldiers or sailors but peasants generally leave town and go to Istanbul where they serve as professional attendants in the bathhouses.” Some, however, did better: At least 26 Albanians became grand viziers in the Ottoman Empire. Given Turkey’s strong economy today, it is no wonder that Albanian adolescents still dream of going to the city at the end of the long road.

And so nearly still within sight of Italy, one begins to plot the journey, following what classical historian Max Carey has called Albania’s best road until the 20th century, then through Macedonia and Greece, parallel in part to a new, €7- billion expressway called Odos Egnatia. Stretching about 300 kilometers, or about one-third of the Via Egnatia, it passes finally under Istanbul’s Golden Gate, a three-bay triumphal arch erected by Theodosius i 40 years after Constantine.

The Roman poet Ovid knew this route well, and he wrote about it from his Black Sea banishment in the year eight ce with his eyes turned longingly west toward home. His route into exile was partly by sea and partly by road after landing at Tempyra, just west of the Evros River near Traianopolis (modern Loutra). Listed as a civitas on the Via Egnatia, it has the largest surviving Ottoman han in the Balkans, and a double-domed and still-steaming kaplıca, or thermal bathhouse.

As the poet wrote in Book Four of his Black Sea Letters, which he probably sent back to Rome along the Vias Egnatia and Appia:

It is a long road; your feet, as you go, are uneven,

and the land lies hidden under winter snow.

When you’ve crossed frozen Thrace, and the cloud-capped Balkan ranges,

and the waters of the Ionian Sea,

then, in ten days or less, without hurrying your journey,

you’ll reach the imperial city.

He was right to mention the winter snow of frozen Thrace, for the road passes Mt. Pangaeon, which at 1,956 meters is certainly high enough to trap travelers caught in a storm. An Albanian proverb states a hard truth about its unforgiving landscape: “If you start on a journey, you will also cross plains, mountains and rocks.”

The route up the Shkumbin River valley in central Albania passes first the town of Peqin, identified as the mansio Clodiana. Its Ottoman clock tower and mosque were both noted by Evliya Çelebi. Here, a spur of the Via Egnatia, running north from the now-deserted Roman town of Apollonia (one of many towns of that name all over the Roman world), joined the main branch. True to a traveler’s guidebook, outside town one spots a Roman bridge as well as the first intact Roman pavers since leaving Durrës.

Fatmir Muho is a 43-year-old taxi driver living in the next town on, Elbasan. A former long-distance trucker, he knows all the region’s roads, both the better and the worse. His derogatory description of some of them is not far from that of the 19th-century German scholar Tafel, who, with unintended irony, had this to say about the old trans-Balkan Roman routes: “These great roads do not seem to have rendered to civilization all the services that civilization may derive from roads today.” Yet it was Anna Comnena, an 11th-century Byzantine princess, who put it best and most simply in the Alexiad, the chronicle of her father Emperor Alexios’ reign, when she wrote about “those winding paths through that impassable region.”

Muho tells of days not so long ago, under communism, when horses were driven across the Macedonian border for sale. Albanian horses, he explains, were for working, and they commanded higher prices in Macedonia, and less fit, less expensive Macedonian horses would be brought back across the border for slaughter. Customs control would have not noticed if the same horses that had previously been taken across had not returned, so Albanian traders made a good living selling their own stock dear over there, buying the stock of others cheap and bringing it back—and not paying a penny of duty.

This professional chauffeur fails to mention if the horses had been driven on the left of the road, as ox carts were driven in Roman times. Some say that left-side drive in the uk is a holdover from its occupation by the Romans.

KM18

The paving stones, often like risen loaves of fresh-baked bread, reappear from time to time through more fields and meadows. The way dips and the houses thicken again into Dardhë village, where sheepfolds are protected by tough Illyrian sheepdogs, a breed of tawny-coated and black-headed guardians known in Macedonia as Šarplaninec, or the Šar Mountain dog. After a day’s hike, a bed in the local school is welcome even if the dogs do bark all night under a full moon.

The town of Ohrid is north of Dardhë, sitting beside the 700-meter-high, mountain-fringed lake of the same name, and the elevations beyond rise more than three times as high. Ohrid is the Lychnidos of the Romans, with an amphitheater and a hilltop castle, and today in summer it receives a large number of northern European sun-seekers who arrive not on the Via Egnatia, but via air.

The 12th-century Arab geographer al-Idrisi wrote of Ohrid, “The town is remarkable for the significance of its prosperity and commerce. It is built on a pleasant promontory not far from a large lake where they fish on boats. There is much cultivated land around the lake, which is to the south of the town. Its circumference is slightly more than three days.” Edward Lear’s description of the main square—“White minarets and thickly grouped planes studded over the environs”—echoes the view today, which he captured also in a watercolor set just outside the Ali Pasha mosque near a still-thriving plane tree.

From Ohrid on to Bitola, the route was known to the Ottomans as Manastir and to the Romans as Heraclea Lyncestis. It cuts through the heartland of the Vlach people, who today still speak a Latin-based language descended from Roman settlers. According to Fotini Tsimpiridou, a Greek anthropologist at the University of Macedonia in Thessaloniki and a specialist in Balkan ethnic minorities, the Vlachs are as open to outsiders as the Pomaks, Slavic Muslims in Bulgaria, are reclusive. It seems fitting that the Via Egnatia, built by their own globe-trotting forebears, should run through their home territory.

Upriver, past an Ottoman bridge that could be the twin of the more famous one in Mostar, Bosnia, one reaches the Macedonian Republic’s border at Qafë Thanë—a mountain pass just east of Lake Ohrid and perhaps the “Pons Servilii” listed on the The Peutinger Map. The journey continues into the lexically confusing region of Greek Macedonia. This is the land of Alexander the Great, his father Philip ii and the family’s Argead dynasty. But not to be outdone by the Greeks are the Turks, who claim this region as the seat of an esteemed lineage of their own, the Evrenosoğuları, headed by Gazi Evrenos Pasha, the ucbey, or march lord, who conquered the Balkans in the late 14th century as general under the grandson of the Ottoman dynasty’s first sultan, Osman i. Evrenos founded the city Yenice-i Vardar, “newish [town] of the Vardar [River],” now called Giannitsa. His tomb today has been rebuilt as a whitewashed and frilly neo-classical confection. Some biographies give the age of the man buried there to be 129 years old, but all that is certain is that he died in 1417.

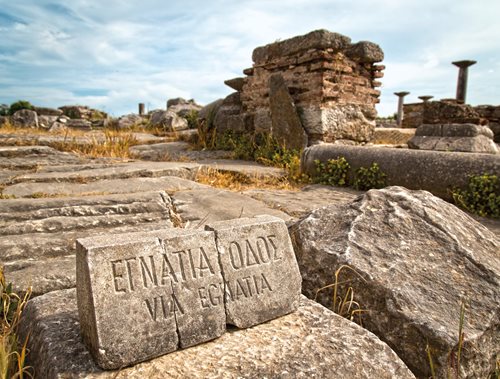

Inscribed in Latin and Greek, this detail of a milestone found near Thessaloniki shows the name of Gaius Egnatius, the second-century Roman senator and governor of Macedonia who led the construction of the Via Egnatia in the second century bce.

Farther east, in Kavala, this Ottoman-built aqueduct was commissioned by Suleiman the Magnificent in the 16th century.

This was an important stop on the Ottoman road system. Built some 1,500 years after the Via Egnatia, Yenice-i Vardar’s center is some distance from the Roman-built thoroughfare, with no signs of it nearby, although its Ottoman monuments, including a clock tower dating from 1753, the Ilahi Mosque with its still-standing minaret—rare in this part of Greece—and hammam are still there, despite being in poor condition.

The way reemerges some six kilometers past Giannitsa at Pella, where Alexander was born, Aristotle taught and Euripides wrote the Bacchae, considered one of the greatest classical Greek tragedies. By the time of the Roman conquest it had been much reduced in importance, and an earthquake in the first century may have made it seem not even worth a stop-over, given that the much grander city of Thessaloniki was nearby to the east.

Pella’s old museum now functions as a trinket factory suppling gift shops countrywide. Plaster copies of the Venus of Milo in all sizes bring to mind what the Roman historian Livy said about the war booty of Macedonia after its defeat at Roman hands: “set out on exhibition, statues, paintings, rare stuff ... manufactured with great pains in the Palace of Pella.”

KM22

They come as a jarring incongruity: concrete anti-tank bunkers built by the communist dictator Enver Hoxha, a response to his unfounded fear of invasion from the neighboring communist army of Yugoslavia’s Marshal Tito. Today, many of the bunkers have been smashed to the ground, their iron rebar picked out and loaded onto mules for recycling down in the valley. Others are used as sheep pens and hay sheds.

Old and new, the Via Egnatia links not only Western and Eastern empires, but also more than two millennia of history over 1,120 kilometers, witnessed by a marker found amid the ruins of Philippi, Greece, left, and a modern sign along the expressway, right, that now traces some 300 kilometers of the old road's path in northern Greece and southern Turkey.

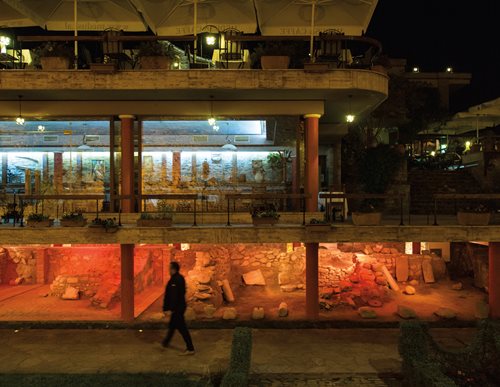

On from Pella, Thessaloniki is Greece’s second largest city. In Roman times it was the first, so crowded with urban traffic that the Via Egnatia was routed around it as a kind of beltway. But history still has a way of intruding into modern nomenclature, so naturally an odos, which is Greek for “road,” Egnatia runs east-west just four streets in from the shoreline, nearly passing under the Arch of Galerius, built by a Danube Valley peasant-turned-Roman emperor early in the fourth century. On the same street are two Ottoman monuments: the mosque of Hamza Bey, dated 1468 and now under restoration, and the locked Bey Hamami, or so-called Paradise Baths, dated 1444.

Thessaloniki is also the birthplace of the founder of the modern Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, and his family home is now a museum incorporated into the Turkish consulate. Greek-Turkish relations have long been difficult, but the mixing of cuisine, architecture and language in this city somehow seems all the more apt given the Via Egnatia’s role in bringing together so many people into a single place.

Anthropologist Fotini Tsimpiridou finds scholarly inspiration from her grandmother Efthalia, who relocated from Keşan, Turkey, to a village on the other side of the Evros River in the 1920s. “She was a simple woman,” says the professor, “but very wise, because she always knew the truth, despite what history tried to tell her. Turkey alone was her patriada—she called it that from nostalgia and cultural identification, because she came from Keşan and didn’t believe the officials when they gave names like Nea Kessani [“New Keşan”] to newly established villages on their side of the border.”

In the east, the road ended—or began, westward—in Istanbul, where the road passed through the city's walls, above, at a place called Porta Aurea, or Golden Gate. The section of wall above is in the area of Yedikule, Turkish for seven towers.

Tsimpiridou also cites the case of influential cookbook author Nicholas Tselementes, who in those same years tried to “Hellenize” what had always been considered as interchangeably Greek and Turkish recipes for basic home dishes. In fact, he “French-ified” them more and “de-Turk-ified” them less by adding béchamel sauce to moussaka, for instance, and astute Greek chefs have been trying to rid it from the recipe ever since.

Moving on to the east, the Via Egnatia passes the mansio of Apollonia (not to be confused with Apollonia, Albania), where an Ottoman hammam and han stand in ruins. Then it’s on to the civitas of Amphipolis, where a recently excavated tomb has excited nationalist politicians with the possibility that it belongs to an offspring or general of Alexander the Great, which they hope would give Greece yet more claim to sole Macedonian heritage.

KM26

After we leave Dardhë uphill in a woodcutter’s truck at dawn, the Rruga Egnatia’s distinctive pavement is soon crossed and once again the eastward way is taken on foot. Shepherds, fields of maize and more haystacks piled up around a central spike lead to Qukës Skenderbej (Alexander Bey) village, after the 15th-century Albanian hero—a nobleman who served in the Ottoman army before breaking away to fight them for his nation’s freedom—named in honor of Alexander the Great. The Siege, another novel by Ismail Kadare, covers his story as seen through the eyes of the Turks, and his statue commands the capital city Tirana’s central square.

Through the foothills of eastern Macedonia and western Thrace all the way to the Turkish border, the Odos Egnatia superhighway cuts like a blade. It also charges hefty tolls. It makes it easy to speed past the old stops mentioned in the Bordeaux Itinerary—mutatio Rumbodona, civitas Empyrum, mansio Herconstroma and the like—without being tempted by the motorway’s exits. Not that it would do any good, because the exact locations of these places are still unknown. Highway construction did help to unearth some sites near the town of Asprovalta, probably the mutatio Pennana, but a nearby site at Syndeterios was covered over in 1980 by a motorcycle track.

The Via Egnatia was originally built only to the mansio Cypsela, modern Ipsala, on the Turkish side of the Evros River. Because the way was informally connected with other, older roads that were later upgraded by the Romans, we only know without precise dating that it was later extended to Byzantium through the dense network of new roads, some going straight along the Sea of Marmara’s coast, past Tekirdağ and Silivri, others running north through the city of Hadrianopolis (modern Edirne), to connect with the Belgrade road, or Orta Kol. In most cases, only the names are known of the stations between Cypsela and Istanbul. At the town of Marmara Ereğlisi, just 97 kilometers from Istanbul, inscriptions on four milestones all begin with the same simple salutation: “Good Luck,” as if to subtly warn travelers from the west to be wary of the big city’s temptations and hazards, of which there were as many then as today.

KM34

From Qukës Skenderbej, the route gradually descends back to the valley floor. Here the pavement’s vestiges disappear amid the detritus of communism’s industrial waste, closed factories and dreary housing blocks. The best way to continue from here forward, after this Albanian mountain trek through the most remote and intact section of the Via Egnatia, is by vehicle, to the Republic of Macedonia’s border and farther along finally to Istanbul, where so many young shepherds and woodcutters have always wished to go.

About the Author

Louis Werner

Louis Werner is a writer and filmmaker living in New York City.

Matthieu Paley

Photojournalist Matthieu Paley specializes in documenting people and regions that are often misrepresented and is committed to issues relating to diminishing cultures and the environment. He is a regular contributor for National Geographic.

You may also be interested in...

A Researcher Chisels New Perspectives on Ancient Art

History

Arts

Zainab Bahrani of Columbia University photographs ancient statues and reliefs carved into the rocks of remote Iraq to create a database for conservators and scholars. The effort is “decentering Europe from histories of art and histories of archaeology.”

The Bridge of Meanings

History

Arts

There is no truer symbol of Mostar, Bosnia-Herzegovina, than its Old Bridge. The magnificent icon of Balkan Islamic architecture was destroyed during the 1992–’95 war—but not for long. Like the multicultural workforce that produced the original hundreds of years earlier, a broad team of architects, engineers and others came together immediately to plan its reconstruction. This summer marked the 20th anniversary of the bridge’s reopening.

Pieces of the Past: Mértola, Portugal Rediscovers its Islamic Roots

History

Arts

Thanks to children who kicked up little pieces of red ceramics while playing on a hilltop in 1977, the town of Mértola, Portugal, has taken its place alongside much of the rest of the country as it rediscovers its Islamic past. Years of excavations have turned Mértola, which lies near the border with Spain, into a destination for both tourists and researchers, and officials have applied to make Mértola a UNESCO World Heritage Site.