Arwad, Fortress at Sea

- History

Written by Robert W. Lebling

Photographs and video by Kinan Ibrahim

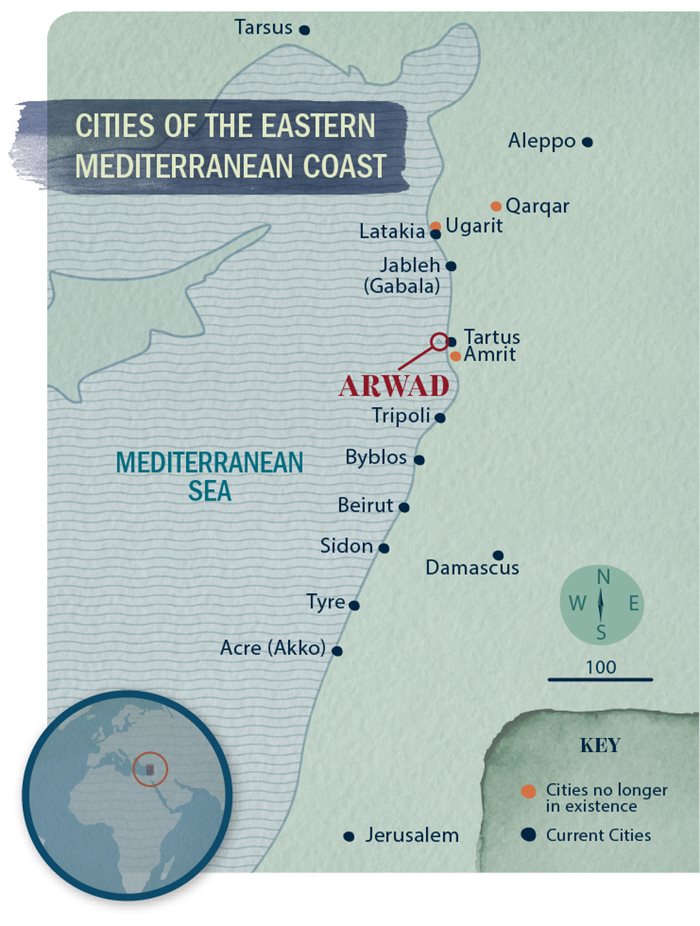

Along the entire eastern coast of the Mediterranean, there is only one inhabited island: Arwad.

Not much more than a dot of rock off the coast of Tartus, Syria, it once dominated a goodly stretch of that coast, ruling the mainland like an offshore castle. War galleys of Arwad fought on the side of the Egyptians, the Assyrians and even the Persians when the tide turned for Greece in the early fifth century bce. More than a millennium and a half later, the island became the last bastion in the entire Levant for the crusading Knights Templar before their final, dramatic expulsion. Though Arwad today is a quieter place, the remains of its massive stone fortifications have many a tale to tell.

In the 1970s, when Syria was at peace, a small group of journalists drove up the coast from Beirut through Tripoli and across the Syrian border. It was a carefree weekend jaunt on a crystal-clear, sunny day. We stopped for a cold seafood lunch at a beach hotel, then headed north to the coastal city of Tartus, where we negotiated passage with a fisherman. He ferried us in his wooden boat that jounced us through the chop as salt spray invigorated our faces. Far above, seagulls swooped, tracking our progress across the channel that for millennia had served as a great natural moat, at times protecting and at times isolating the island that was small enough to appear to float on the sea. About three kilometers west of the port, we reached our destination, a warren of narrow streets and seaside restaurants crowned with a massive fortress: Arwad.

Remnants of ramparts that once circled all but Arwad’s harbor side, these few weathered blocks likely date back at least as far as the Seleucid era that followed Alexander the Great.

It was not unlike other small Mediterranean port towns. Its population ranged between 5,000 and 10,000 depending on the season, all living atop 20 hectares of rock. Fishing, boatbuilding and tourism kept everyone going, as it has for much of the last century, although recently all three have declined with the war on the mainland.

The Greek geographer and historian Strabo wrote that the island he called Arados was founded by exiles from the Phoenician city-state of Sidon. (Arwad’s Phoenician residents are thought to have called their island city Aynook.) Arwad also appears as Arvad, and its people Arvadites, at least twice in the Old Testament, where they are noted among the tribes of Canaan. After Alexander the Great conquered the Eastern Mediterranean in the fourth century bce, coins minted by the islanders bore the Greek legend “Arados.”

Physically, Arwad is a low, barren slab of rock, bereft of arable soil, natural springs or any other water resource, some 800 meters from northwest to southeast and about 500 meters wide. Always densely settled, its multi-story buildings gave rise to its sobriquet, “five-story city,” and its inhabitants in Strabo’s Roman-ruled times (when the island was called Aradus) lived in “houses of many stories,” the geographer tells us.

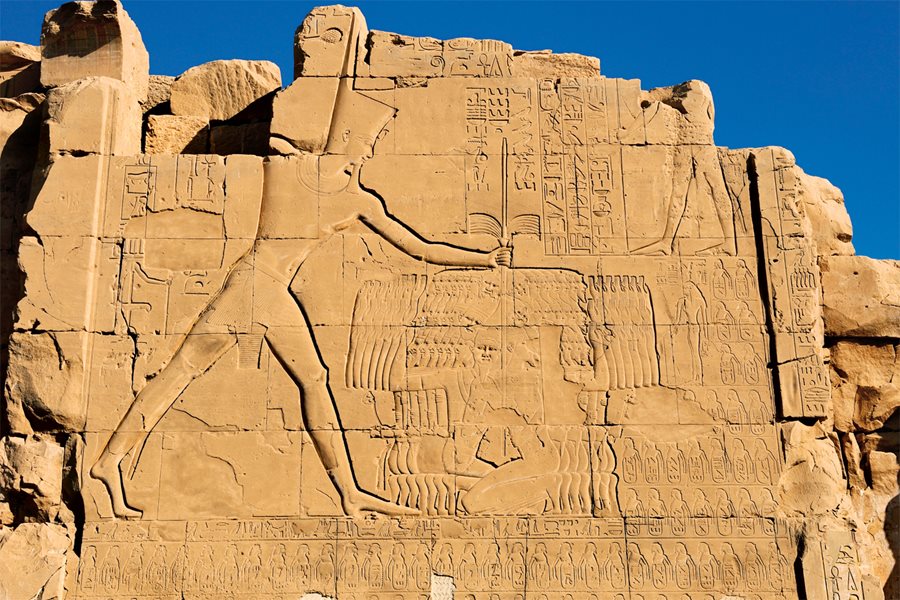

Bereft of resources, it was Arwad’s strategic position along the Levantine coast that made it attractive to the powerful. In Karnak, Egypt, on the seventh pylon at the Temple of Amun-Ra, hieroglyphics from the early 15th century bce chronicle Pharaoh Thutmose iii’s victories during his fifth campaign against the northern Syrian city-states, which included the island of Arwad.

Near the center of the island protrudes the Citadel of Arwad, a rectangular fortress raised sometime in the 13th century but now largely Ottoman, though it retains Mamluk and Crusader features. Two thousand years before its first stones were laid, on this site stood the palace of the Phoenician kings. On the eastern side, facing the mainland, a smaller, square Ayyubid Arab castle, dating from the late 12th century, overlooks the two natural harbor areas that, side by side, once hosted naval fleets, but now are filled with fishing boats, yachts and the ferries that ply to and from the mainland.

The island was once insulated also by a massive outer city wall made of gargantuan stone blocks. As historian Lawrence Conrad describes it, in Byzantine times “the great walls surrounding the island on all but the harbor side were at least 10 meters high in places and were built of tremendous blocks up to six meters long and two meters high.” The walls, according to Conrad, dated at least to the Seleucid era that followed Alexander the Great, and probably even to the Phoenician era before. Much of this protective structure was razed after the Arab takeover in 650 ce; other parts of the walls were brought down after the Mamluk expulsion of the crusading Knights Templar in the autumn of 1302. Only a few segments of the great wall survive, and they tower dramatically near the water’s edge, relics of a seemingly impossible feat of engineering.

Under Ottoman rule when this aquatint was produced in 1810, Arwad’s 12th-century Ayyubid castle lay largely abandoned, though commerce continued from the shore and harbor, visible in the background.

Yet we know that Phoenician architects and masons routinely worked with incredibly great blocks of stone. In their earliest monumental structures along the Eastern Mediterranean, foundations of buildings were hewn straight from native rock, squared off and smoothed, followed by courses of detached blocks whose dimensions often exceeded several meters and sometimes reached five meters or even more—as with the wall of Arwad.

Arwad’s lack of water presented the island’s most serious challenge to habitation. Strabo recounts that Phoenicians collected rainwater and channeled it into cisterns, and that they shipped containers of fresh water from the mainland. Perhaps the most resourceful solution came from the fortuitous discovery—probably by sponge and coral divers—of an undersea freshwater spring, not far from the island in the channel between Arwad and the mainland. This spring, says Strabo, was exploited as a last resort when war or other crises interrupted water supplies from the mainland:

… into this spring the people let down from the water-fetching boat an inverted, wide-mouthed funnel made of lead, the upper part of which contracts into a stem with a moderate-sized hole through it; and round this stem they fasten a leathern tube (unless I should call it bellows), which receives the water that is forced up from the spring through the funnel. Now the first water that is forced up is sea-water, but the boatmen wait for the flow of pure and potable water and catch all that is needed in vessels prepared for the purpose and carry it to the city.

Arwad first appears in recorded history in the 15th century bce, when the naval fleet of Egyptian Pharaoh Thutmose iii took control of the island. Egypt’s greatest conqueror, Thutmose followed an expansionist agenda that was aided by keen tactics and advanced weapons. He subdued Arwad (then “Arvad”) in 1472 bce, during his fifth campaign into northern Syria. On the walls of the Temple of Amun-Ra at Karnak, the pharaoh listed the conquest in a hieroglyphic account of the campaign that remains legible today.

But Egyptian rule did not last long, and by the 14th century bce, the post-Thutmose Canaanite mini-kingdom of Arwad was an important seaport and trade center along the route between Egypt to the south and the Amorite port of Ugarit up the coast, near Syria’s modern border with Turkey. This was an era of conflicts among small kingdoms, and the clay tablets known as the Amarna Letters recording Egypt’s dealings with nearby powers contain at least five references to “men of Arvad” as naval mercenaries whose ships had blockaded ports across the western Levant, including Sumuru (Simirra), Byblos and Tyre, according to Jordi Vidal, a historian at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. Like other scholars, he believes Arwad most likely furnished mercenary warriors and warships to whoever could afford them.

Tooled in bronze around 853 bce, this small relief panel is one of many chronicling the battles of Assyrian King Shalmaneser iii against coastal city-states. Although it may literally depict Tyre, which was an island a few hundred meters offshore until Alexander the Great’s successors built a causeway to the mainland, the ferrying of goods and soldiers from a fortified island to the coast is applicable no less to Arwad, whose ruler took part that year in a coalition rebellion against Assyrian domination.

A couple of centuries later, the 12th century bce was a time of chaos and unrest as the region dealt with migrating invaders of still-unknown origin called the “Sea Peoples.” Major powers, including the Mycenaeans and the Hittites, suffered collapse. Out of the ashes and turmoil emerged new powers, including the coastal Canaanites known to the Greeks as “Phoenicians”—skilled sailors and canny merchants so named for their trade in phoinix, the Tyrian royal purple dye coveted by fashion-conscious elites throughout the Mediterranean whose secret source was murex sea snails. The Phoenicians organized into independent city-states, built confederations and used their seafaring skills to dominate trade all the way to the western reaches of the Mediterranean, to Morocco and Iberia. (It was from these people that the world’s first alphabet emerged in about 1000 bce, soon spreading to the Greeks and, eventually, the Romans.)

Among the Phoenicians, their four leading city-states were Tyre, Sidon, Byblos and Arwad. Historian Philip Hitti calls the quartet “a brilliant cluster whose names glitter through the pages of the Iliad and the Bible.” Two of these were built on islands: Arwad and Tyre, which the Greeks first connected to the mainland by a causeway (today, it is fully filled in). Of the four, Arwad was the northernmost, and it was the only one oriented culturally and economically toward northern Syria.

Details are sparse on how Phoenician culture first flowered in the 12th and 11th centuries bce. We do know from the Amarna Letters that in this period Assyrian King Tiglathpileser I visited Arwad and boarded at least one of its ships. He accepted tribute from the city-states of Byblos and Sidon—and presumably from Arwad as well.

Up to the 11th century, Egypt, too, remained influential in the Levant. But around 1000 bce Egyptian power waned with the invasions by the Sea Peoples and the ensuing disruption of Late Bronze Age cultures. Trade throughout the region fell off.

A new geopolitical order emerged. Flourishing Phoenician settlements came into their own after centuries in the shadow of hegemons Egypt, Ugarit and Assyria. Where the Levantine coast had previously relied on imported Aegean goods and wares, now Phoenician cities began to reverse the flow and export to the Greeks and others such products as ceramics, cedar wood, blown glass and the avidly sought purple textile dye, as well as such valuable services as boatbuilding, navigation and construction of monumental buildings.

During this time, Arwad exerted control over mainland settlements opposite the island. The closest colony was known as Antarados (“Opposite Arados”), from which comes the modern name Tartus. Arwad also founded, controlled and eventually absorbed the Phoenician coastal city of Amrit (Marathos to Greeks), some six kilometers south of Tartus.

Arwad and two other Phoenician powers, Sidon and Tyre, in a kind of joint venture, founded yet another colony some 50 kilometers south of Arwad, at a place they named “Tripolis,” or “Three Cities” in reference to the founders, and today this is Tripoli, Lebanon. Greek geographer Scylax describes Tripolis as literally three cities in one, noting that the colonists from the parent cities each kept a separate walled quarter. Strabo indicates that Arwad’s overall dominion extended from the northern Syrian city of Gabala (modern Jableh, near Latakia) south to the Eleutheros River, now al-Nahr al-Kabir (“the Great River”), which separates Syria from Lebanon.

Ever since the 13th century bce and up through the ninth century bce, the city-states often maintained varying degrees of autonomy by paying tribute (taxes) to the Assyrians, the regional superpower. Although records show Phoenician tribute to Ashurnasirpal ii in about 876 bce, Arwad soon balked, and in 853 bce the island joined 10 other kingdoms in rebellion against Assyria. Arwad’s King Mattan-Baal sent 200 soldiers to northern Syria to engage in the Battle of Qarqar in which the 11 rebel coalition forces set themselves against the army of Assyrian King Shalmaneser iii. In surviving inscriptions found in present-day eastern Turkey, notably on the Kurkh Monolith of Shalmaneser, the Assyrians claim victory, but the actual outcome is less clear-cut: All 11 rebel rulers, including Arwad’s Mattan-Baal, held onto their thrones.

In the late seventh century bce, Assyria’s regional power collapsed forever. Egypt made a brief effort to reassert control over the Levant, but it was the Babylonians who became overlords of the Phoenician coast.

In the sixth century bce, an unnamed king of Arwad appears in the official records as a regular at the court of Nebuchadnezzar ii of Babylon. In those days, carpenters from Arwad and Byblos were known for their skills in woodworking and boatbuilding, and they had found employment in the Babylonian capital.

Fishing and boatbuilding have been practiced on Arwad since Phoenician times; in the sixth century bce, woodworkers from Arwad were employed in the royal court in Babylon, now in Iraq. Though Arwad exports fish to the mainland, both its seaside restaurants and its population of up to 10,000 in the summer rely on ferries to import nearly everything else. Its economy today is depressed by the war in Syria, and it has accepted several hundred mainland refugees.

In 539 bce, Cyrus the Great, king of Achaemenid Persia, conquered the Phoenician city-states, and Arwad became a vassal. In 480 bce, warships from Arwad joined the ill-fated Persian fleet in battle against the Greeks and their allies at Salamis, which decisively thwarted Persian aspirations for further Greek conquest. Maharbaal, one of only two kings of Arwad whose names are known for certain during the Persian period, is assumed to have taken personal command of his kingdom’s ships during the fight.

It was about a century and a half after the Battle of Salamis that a Macedonian conqueror named Alexander swept through Asia Minor and dealt Persia another defeat at Issus in southern Anatolia, in November 333 bce. Alexander continued southward to subdue the Phoenician city-states and take command of their fleets before he turned east into Asia. When he arrived on the mainland near Arwad, it went like this, according to Arrian, a prominent Greek historian of the first century bce:

[He] met on his way Straton, the son of Gerostratos, king of the Aradians, and associates of Arados…. When he met Alexander, Straton crowned him with a golden crown and gave him the island of Arados, Marathos, the town located on the mainland in front of Arados, large and rich, Sigon [sic], the city of Mariamme and all their territory.

In other words, on behalf of his father King Gerostratos of Arwad, Straton surrendered the realm. After Gerostratos, Arwad’s monarchy lapsed.

With Phoenician power and dependence on the sailors of the island gone, Arwad began to slip from the larger stage of history for more than a thousand years. Its fishermen, however, continued to work their nets, bringing home boatloads of fresh seafood for generations of local markets. From their vantage point across from the mainland, the small population of Arwad became spectators to history’s tides. When the Greek Seleucids ruled Syria after the death of Alexander, Arados sided with them; when the Romans succeeded the Greeks in Egypt and Asia Minor, Arwad accepted their rule, too.

Literally depicting their attachment to the Eastern Mediterranean, Crusaders mortared this relief plaque of a lion chained to a palm tree onto the wall alongside the gate to Arwad’s citadel.

But they were not exactly submissive all the time, particularly when it came to paying tribute. Fourth-century ce historian St. Jerome reports: “Curtius Salassus [a tax farmer and officer of Mark Antony] was burnt alive along with four cohorts on the island of Aradus, because he had collected tribute too harshly.” This took place between 44 and 41 bce, restive years due to the assassination of Julius Caesar and the ensuing power struggle of Octavian, Lepidus and Mark Antony whose effects rippled even into Asia Minor. By and large, Arwad remained peaceful under Roman rule. Strabo notes that although the doughty sailors of Arwad were invited by the Cilicians to join in unspecified “piratical” ventures, “they would not even once take part with them in a business of that kind.”

Later apocrypha maintain that Paul of Tarsus, apostle of Jesus of Nazareth, visited Arwad during his journey through Asia Minor to Rome, but Arwad does not appear in further chronicles until Rome had been replaced by Byzantium as a coastal power and it, in turn, was supplanted by Muslim Arabs. Around 650 ce, the naval fleet of the Arab governor of Syria, Mu‘awiya ibn Abi Sufyan, who later founded the Umayyad dynasty, conquered Arwad.

The Syriac Chronicle of 1234, a primary reference source for scholars of the Crusades, describes the Arab siege, made brief by the island’s lack of local food and water. After initial resistance, Arwad surrendered under Arab terms that allowed the Christian population to resettle either in mainland Syria or any other country. When the last citizen had departed, the governor ordered the walls razed and the city torched. Mu‘awiya was determined that Arwad would never again operate as a Greek naval base so close to the mainland. Arwad remained a “no man’s land” for nearly 500 years.

At the end of the 11th century ce, encouraged by the Pope in Rome, Latin Christian “Crusader” armies set out from Western Europe, and in 1099 they captured Jerusalem. They held the city and its surrounding territory as the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem for 88 years. Key components of the kingdom’s military power were the military-religious orders, particularly the Knights Templar, whose ostensible mission was to protect Christian pilgrims, and the Knights Hospitaller, or Knights of St. John, who ran hospitals and clinics in the Levant.

In 1187, Salah al-Din Yusef ibn Ayyub, known in the West as Saladin, commanded an Ayyubid army to defeat the Crusaders at Hattin on the western coast of the Sea of Galilee and take Jerusalem back under Muslim rule. The Crusaders retreated northwest to the port city of Acre (now Akko). The following year, Saladin’s army recaptured Tartus, opposite Arwad. Although the Templar headquarters there withdrew across the waters to Cyprus, a small number of Templars managed to hold onto the castle keep, which they continued to use as a base for the next 100 years.

The Crusaders continued, however, to lose strategic holdings. In May 1291, the Mamluks under Sultan Al-Malik al-Ashraf Salah al-Din Khalil ibn Qalawun recaptured Acre. Frankish King Henry ii responded by relocating with his nobles and fighters, including many Templars, to Cyprus. On August 4, Mamluk forces seized the Templars’ castle keep at Tartus. Ten days later, all that remained to the Crusaders south of the Syrian Gates in Turkey was the small Templar presence on Arwad.

Above: Now conserved as a historic site, Arwad's Citadel saw its last major military event in 1302, when its garrison of more than 1,000 men serving the Knights Templar was defeated by Mamluk troops who arrived in 16 ships dispatched from Alexandria, Egypt. Below: children play in front of a vaulted passageway that echoes the island’s past.

In the year 1300, Henry ii, now king of Cyprus, was plotting a return to the Syrian mainland using what remained of the forces of the Knights Templar, the Knights Hospitaller and an order of German warrior monks, the Teutonic Knights. Arwad would be his bridgehead for an attack on Tartus, which he devised in secret alliance with Ghazan, Mongol khan of Persia, who planned to attack Mamluk Tartus from the east. Ghazan, for his part, envisioned this as the first stage of a wider alliance with the Franks against the Mamluks throughout Syria and Egypt.

In November, some 600 Crusader troops ferried from Cyprus to Arwad. From there, led by Templar grand master Jacques de Molay and the king’s brother Amaury of Lusignan, the knights launched raid after raid on Mamluk Tartus, praying all the while for the promised arrival of the Mongols. Weather, it turned out, delayed their hoped-for allies, and Ghazan, sensing a plan gone awry, canceled his attack. The Crusaders withdrew again to Cyprus, leaving only a tiny garrison on Arwad.

A year later, after vigorous appeals for support from De Molay, Pope Boniface viii officially bestowed Arwad Island on the Knights Templar. The Mamluks remained an ever-present threat to this last, now officially Frankish bastion, so its fortifications were bolstered, and Arwad received a permanent garrison of 120 knights and sergeants, 500 mercenary Syrian bowmen, and 400 squires and other non-fighting servants, all under the command of Templar marshal Barthélemy de Quincy. This was a sizable force: fully half the strength of the garrison that had held sway over Jerusalem.

In September 1302, the Mamluks attacked Arwad. On orders from their sultan, Al-Nasir Muhammad, Mamluk commanders dispatched 16 war galleys from Alexandria, landing their troops at two locations on their target island. The Templar garrison, defending from the Citadel and the fortress in the harbor, fought back, but they were besieged, and food and water quickly ran short. The Mamluks agreed to give the Templars safe conduct and let them seek refuge in any Christian country that would take them.

The surrender terms were a ruse. When the Templars emerged from their fortifications, the Mamluk forces attacked. Templar leader Barthélemy de Quincy was killed, and the remaining defenders were taken prisoner. Medieval Cypriot chronicles report that the Syrian bowmen were beheaded, the servants and other non-fighters were enslaved, and the surviving Templar knights, said to number in the dozens, were hauled off to prison in Cairo’s Citadel. Only a few, after years of negotiations, were ever freed.

Arwad’s dense settlement gave early rise to its sobriquet, “five-story city,” and inhabitants even in Strabo’s Roman-ruled times lived in “houses of many stories,” the geographer tells us. Across the water that has both isolated and protected Arwad for more than three millennia lies the city of Tartus.

Six hundred years passed. After World War i, the tiny island of fishermen and boat builders became subject to the French mandate over Syria. The dungeons of its old fortress were still usable enough to imprison Arab nationalists, as the captives’ still-visible graffiti attests.

Most recently, it was in June 2013 that three motor launches made the 20-minute sea crossing from Tartus to deliver relief supplies from the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (unhcr) for 119 of the island’s poorest families and 60 refugee families who had fled from the Syrian revolution and ensuing warfare, mainly from Homs and Aleppo.

The unhcr staff reported that the economy on the tiny island had deteriorated. Fisheries were suffering because fewer mainland families were coming to Arwad’s restaurants, fewer customers were buying seafood, and there were growing concerns among fishermen about their own safety on the water.

But the Syrian government had not given up on Arwad. In 2014, Syria’s tourism minister Bishr Riyad Yazigi and then-culture minister Lubana Mshaweh presided over the laying of a cornerstone on Arwad for a four-star hotel resort complex. Amid the ministers’ pledges to the islanders for archeological conservation and support for handicraft traditions on the one hand, and the tears of war flowing on the mainland, the next chapter of Arwad’s long history remains, rather like the tiny island itself, at sea.

About the Author

Kinan Ibrahim

Kinan Ibrahim (kinaneb@gmail.com) is a photographer and information technology professional living in Tartus, Syria.

Robert W. Lebling

Robert W. Lebling (lebling@yahoo.com) is a writer, editor and communication specialist who lives and works in Saudi Arabia. He is author of Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar (I.B. Tauris, 2010 & 2014), and he is co-author, with Donna Pepperdine, of Natural Remedies of Arabia (Stacey International, 2006). He is a regular contributor to AramcoWorld.

You may also be interested in...

When Metalsmiths Found Their Groove

Arts

History

Opulent pieces found from some 700 years ago are now understood to be made of a common metal alloy that, in the 12th century CE, metalsmiths in the Turkic Seljuk dynasty transformed into luxury ware. Today, such pieces are as iconic of Islamic art as lavishly illustrated manuscripts or tilework tessellated with arabesques and geometry.

The Bridge of Meanings

History

Arts

There is no truer symbol of Mostar, Bosnia-Herzegovina, than its Old Bridge. The magnificent icon of Balkan Islamic architecture was destroyed during the 1992–’95 war—but not for long. Like the multicultural workforce that produced the original hundreds of years earlier, a broad team of architects, engineers and others came together immediately to plan its reconstruction. This summer marked the 20th anniversary of the bridge’s reopening.

A Researcher Chisels New Perspectives on Ancient Art

History

Arts

Zainab Bahrani of Columbia University photographs ancient statues and reliefs carved into the rocks of remote Iraq to create a database for conservators and scholars. The effort is “decentering Europe from histories of art and histories of archaeology.”