The Gown That Steals Your Heart

- Arts

Written by Kay Hardy Campbell

Art by Leela Corman

When the head of the house, or a son, returns from a long journey or the pearlbanks, the woman of the house hangs up on a pole … one of her best and most brilliantly coloured thaubs. Among townswomen, this is hung up on the roof.

—H.R.P. Dickson, The Arab of the Desert, 1949

This custom, known as al-raayah (“the banner”), centered on a woman’s holiday gowns: colorful, often ceremonial garments at the top end of her ensemble. Similarly to the coastal and townsfolk Dickson described, Bedouin women, too, would place a brightly colored thobe on a pole in front of the tent to welcome home a traveler or “when an important shaikh or personage is expected to arrive at or pass a camp,” wrote Dickson, one of the foremost Western experts on Bedouin life of the early 20th century.

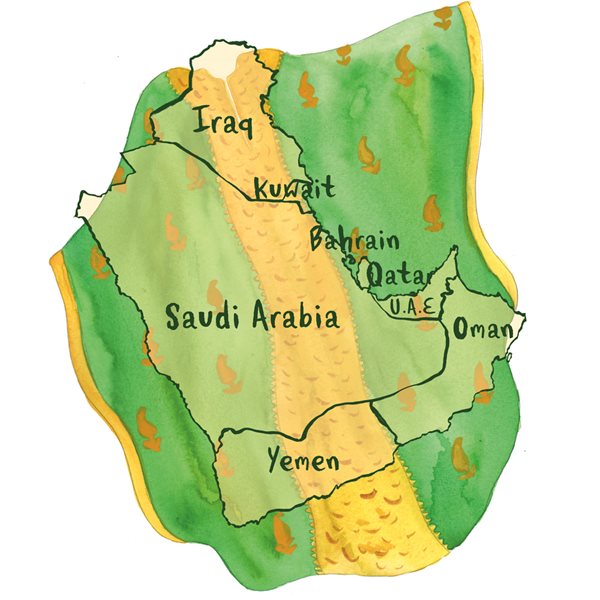

In English, the Arabic word thobe translates simply as “garment.” Today, although it most often refers to the floor-length shirts, often of plain white, worn by men throughout the Arabian Peninsula, it is used also for what is nearly that shirt’s opposite: amply cut, colorful, often highly decorated robes worn by women inside the home or at parties of family or friends. Once commonly worn in almost as many styles as there are regions of the Peninsula, the women’s thobe is enjoying a fashion revival from Iraq and Kuwait down into eastern and central Saudi Arabia, as well as the coastal states of Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates (uae) and parts of Oman.

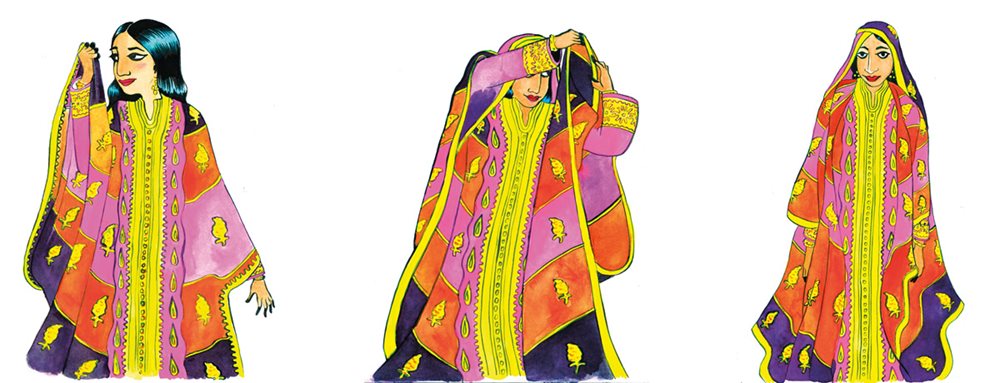

All women’s thobes share a few basic characteristics: cuts that are large and square, or nearly square; side panels that open to form billowing sleeves (some with beautifully decorative gussets); and, in many varieties, length in back enough to trail on the floor.

During the holy month of Ramadan, thobes can be popular at nighttime gatherings. Thobe styles old and new appear here, left to right: Kuwaiti-style thobe with V-neck opening; modernized and belted version of a thobe based on a Faisal Alrayes design; young woman checking her smartphone in a striped mufahhah thobe; pink thobe al-nashal with its signature full floor-length front panel of embroidery; thobe with crescent moon and stars, also based on a Faisal Alrayes design; sambusak–style thobe covered with gold triangles, based on a design by Mohamed Saleh; and a vintage Iraqi thobe known as a hashmi.

Women wear such thobes over other layers, light or heavy depending on the season. (Wearing layers is a hallmark of Arabian women’s traditional dress.) For example, in the Najd region of central Saudi Arabia, as well as east to the Gulf coast, a woman would traditionally put on long pantaloons, gathered at the waist, called sirwal. On top of that, she wore a long gown with fitted sleeves but generally not “waisted” (tighter at the waist). These garments, too, have many regionally distinctive names: dishdasha, dira’a, miqta’ and kandurah; those with more defined waists were nafnuf or just gawan—after the English “gown.” This layer could be of sturdy cotton, lightweight wool, satin, polyester or silk, depending on the season, a woman’s social position, her lifestyle, and the fashion of the time and place.

It was on top of this that a woman pulled on the loose-fitting thobe. In some places, thobes did double duty both as holiday gowns and as more daily cover-ups. Designed for versatility, a thobe allows a woman to lift its neck opening to cover her head; alternatively, she can drape one or both sleeves over her head.

Like a living thing, fashion ebbs, flows and at times folds back on itself. The origins of the women’s thobe are unknown. Some look to its ancestry in the voluminous ceremonial over-garments worn in the courts of the Umayyad and Abbasid periods, and others look back even farther, to Byzantine times.

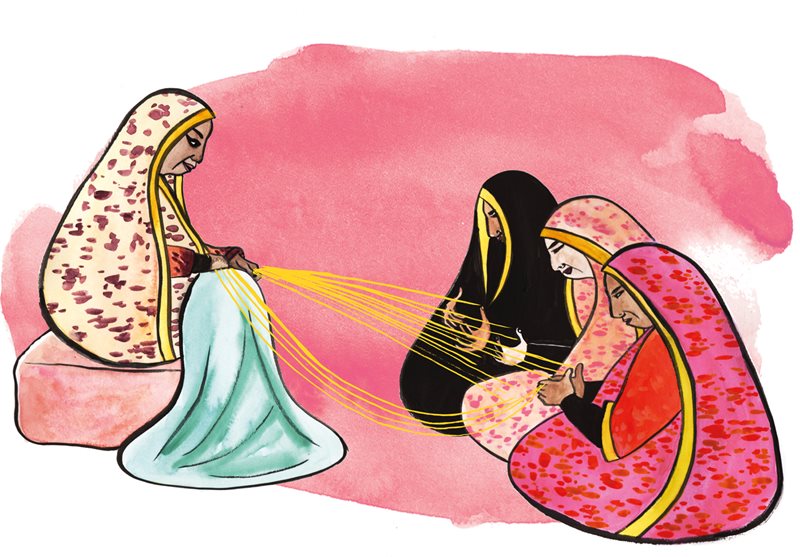

Women wore thobes in so many places in the Arabian Peninsula that, over time, several styles developed. Among the Bedouin of central Saudi Arabia’s Najd region, thobes were made of dark cotton, sometimes decorated with colorful embroidery and strips of colored fabric sewn in, including natural silks in cerise, turquoise and gold. In the Najd’s towns and cities, as well those east in Kuwait and southern Iraq, women wore thobes of finer fabrics, such as black or red silk, tulle and touches of lace, with lavish gold and silver embroidery and sequins at the neckline, sleeves and hem.

In the past, local tailors and women at home sewed and embroidered most thobes, while the more elaborate ones came from tailors in India. These days, most thobes for sale in the Gulf are imports from India or made locally by Indian tailors.

Left: Bahrain's female athletes wore thobes for the parade that opened the 2012 Olympics in London. Middle: Egyptian singing legend Um Kulthum visited Kuwait in the 1960s and donned a Kuwaiti-style thobe at a social occasion. Right: Mary Eddy, whose husband, William Eddy, translated at the historic meeting in 1945 between Saudi King ’Abd al-’Aziz Al-Sa’ud and us President Franklin D. Roosevelt, wore a thobe ensemble gifted to her by the King. It is now part of the collection at the Mansoojat Foundation in London.

Today in the Gulf region, if you stroll through malls, streets and markets where women’s attire is sold, you may catch a glimpse of an exceptionally brilliant-hued, heavily embroidered thobe. Whether it is a royal purple, a bright red or a rich lapis blue, it will be decorated in front from neckline to floor with a panel of intricate gold or silver embroidery: This is the elegant thobe al-nashal (or just thobe nashal), the signature women’s thobe style all the way from Kuwait into eastern Saudi Arabia, over to Bahrain and down to Qatar.

“The thobe nashal is the queen of thobes, in terms of its splendor and the density of its embroidery,” explains Mohamed Saleh, head of the Bahrain-based thobe manufacturer Saleh for Zari, in a Ministry of Culture video.

His company is one of a handful that not only designs and sews high-quality thobes, but also has imported and manufactured women’s thobes since 1950. It has several workshops, all in Bahrain. Prices start around $500, and the most customized thobe might cost up to $10,000.

One spring day last year, the firm’s showroom in downtown Manama’s Yateem Center mall was bustling with customers ordering thobes for Ramadan nights that would be full of visits among friends and families. In addition, it was wedding season, and Saleh was arranging deliveries to brides and their families for events like the traditional henna night, when the bride’s hands and feet are decorated, and for the wedding-night party itself. Typically, the bride and female wedding guests don different ensembles each night; the bride usually wears a white gown on her wedding night.

Switching amid Arabic, English and Hindi, Saleh carries on multiple conversations with his customers and staff. When there is a rare lull, he expounds on the history and styles of thobes in the region.

The simplest, he explains, is called a korar, which is worn every day at home by Bahraini and other Gulf women. It is made from cotton and polyester fabric in all kinds of patterns with chain-stitch embroidery at the neck opening and sleeves. Older women wear korars for formal occasions, and younger ones use them more informally.

No one, he says, not even historians, knows the true origin of the term “thobe al-nashal.” One meaning of nashal, he notes, is “pickpocket,” and thus he says he likes to think that it’s the thobe “so beautiful it steals your heart.”

Dressed to greet important visitors, a Bedouin woman would often don her best thobe and bring a bowl of camel milk. The Bedouin thobe of the Najd region in central Saudi Arabia features the same inset stripes as the mutaffat style of the Najdi towns and echoes the al-mufahhah style thobe well-known in Bahrain.

Thobe al-nashal and her many cousins are worn from Iraq to parts of Oman.

And a “pure” thobe al-nashal just might do that, with its brilliant color and its front panel of dense gold and silver embroidery that reaches to the floor. But the name, he cautions, is tricky: There are endless variations. For example, in Najd, it might be called thobe mukhattam, a name that refers to its vertical bands of embroidery, but the cut is wider and the sleeves are longer, the easier to fold them back to show off the sleeve embroidery.

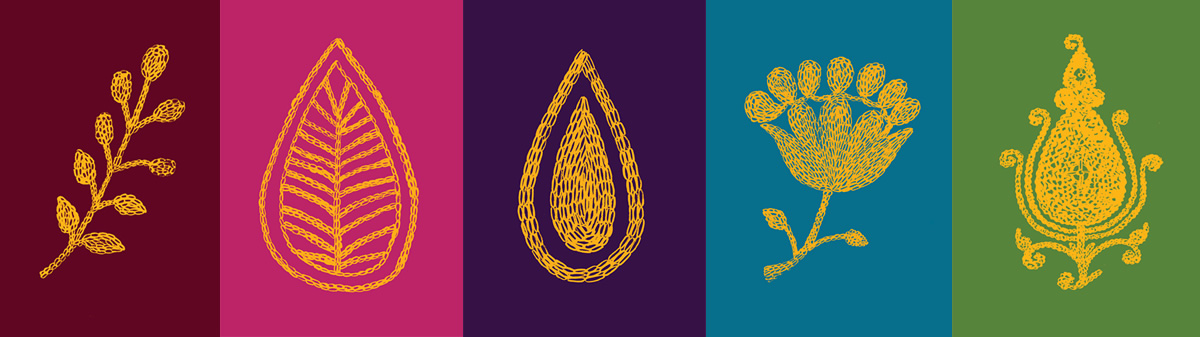

In Bahrain, Kuwait and Qatar, the manthur (“scattered”) style of embroidery is more common. Less ornate at the neckline, it drops down the front a meter or less. Since it uses less thread (which on the very best thobes is made of gold), and consequently less labor in ornamentation, it’s more affordable. The name actually refers to small embroidery motifs that are sewn all over the rest of the dress: paisleys, flowers, fanciful medallions, small circles or whatever a designer or customer fancies.

Bahrain is also famous for a striped thobe called mufahhah, named for the multicolored strips of fabric (fahhah) sewn together and embellished with embroidery and sequins. This echoes the style that townswomen and Bedouin in Najd sewed out of colorful remnants—only in the towns, they call it mutaffat, literally “taffeta’d,” or “the dress with taffeta.”

In Iraq, the thobe also goes by the name hashmi, which is possibly a reference to the country’s early 20th-century Hashemite rulers. In Kuwait, the traditional style was to make the garment from more sheer netted fabrics like tulle, and to sew a smaller embroidered panel in front. The neck opening also tended to be more open, rounded or with an elongated V-shape.

In the Emirates, women’s thobes are often made from patterned fabric, and there is little embroidery on the thobe itself. Instead, there is fancy embroidery on the tight sleeves of the dress underneath, the kandorah; another distinction is that the neck embroidery panel of Emirati thobes is often square.

Just before her wedding, a bride wearing an Emirati-style thobe is being decorated with henna. The henna artist and her companions wear the korar, a less extravagant style usually made of cotton or polyester, often from printed fabric. Although the korar has been traditionally favored by older women, younger women are adopting it today as an informal cover-up.

On all types of thobes, the embroidery designs change much with the times. Decades ago, it was all about floral patterns and ornate medallions, as well as the crescent moon and star (hilal wa najmah). Today peacocks and butterflies appear on thobes. In the 1990s Saleh introduced fanciful curlicues called darb al-hayyah, or “snake trail.” These days, some customers even like to have a family name worked into the embroidery.

Paging through his photo album of custom orders, Saleh stops to point out one black thobe completely covered with small embroidered gold triangles. He calls this sumptuous (and very expensive, he adds) style sambusak, since the embroidery triangles are shaped like the savory pastries from which the name is taken.

Then he turns to a photograph of a rare gem: a thobe with a large triangle of gold embroidery at the base of the front. This, he says, is a thuraya (“Pleiades”) thobe. It is so named, he says, because the appearance of the star cluster in the sky in September marked both the end of summer and, more importantly for the woman wearing the thobe, the end of the pearl-diving season.

A century ago in Bahrain and Kuwait, diving for natural pearls took men to sea for several months each summer. When the pearling ships returned, the crews’ families greeted them on shore, the women and girls wearing their best thobes. According to Saleh, only the wives of the ship’s captains would wear a thuraya style, which was expensive; some even had gold coins sewn onto them.

The sleeves of thobes are extra-wide, in part so they can be draped over one’s head for a quick cover, but also to show off embroidery at the sleeves. This mufahhah, or striped thobe, is famous in Bahrain.

In recent years, women’s thobes of various kinds have been turning up in modern places. At the 2012 Olympics in London, the female athletes from Bahrain wore three types in the opening parade: a nationally colored red manthur and two versions of the striped mufahhah. The 2009 short feature film The Good Omen by Bahrain director Mohammed Rashed Bu Ali took its title from a variation on the al-raayah or “banner” tradition of hoisting a woman’s thobe on a pole above a house to celebrate the return of a family member: In this case, a despondent widower’s spirits are lifted when his wife’s ghost visits and he raises her thobe over his house. He calls it thobe al-bisharah, the “thobe of the good omen.”

Fine thobes are also beginning to appear in museum collections. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has at least two, and the British Museum is home to the thobes of Dame Violet Dickson, wife of H.R.P. Dickson. In London, the nonprofit Mansoojat collection of Arabian women’s dress features several striking examples, including one given by the founder of Saudi Arabia, King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz Al-Sa’ud, to Mary Eddy, wife of us Colonel William Eddy, who served as Minister Plenipotentiary to Saudi Arabia and translated between the King and President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the historic meeting of the two on the USS Quincy in the Suez Canal in 1945. Another fine, red thobe nashal in that collection was originally a gift to an American friend from Saudi Arabia’s Queen Effat, wife of King Faisal.

In addition to visiting shops, women now often buy thobes like any other clothing—online, often interacting with designers who post on Instagram and their own websites.

In Boston, the Museum of Fine Arts received several thobes from Dawn Nordblom, an American who lived in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province. In recognition of her gift, the museum’s Textile Society invited Arabian dress specialist Aisa Martinez to speak at the museum. Martinez is also a curator for the Zayed National Museum Project in Abu Dhabi.

Garments, she said, “are active participants in creating and fostering a sense of cultural identity … [and] a form of non-verbal communication,” one that “defines our roles in society” through “a language of personal adornment.” They show which group you belong to or which tribe you’re from, your wealth, status and social position.

Thobe customs are always changing, and popularity waxes and wanes. While weddings were once the principal occasion for a thobe, women today follow international fashion trends, or wear traditionally inspired gowns that mix and match old and new, Morocco with Pakistan and Paris. While in the past women often danced in their thobes at weddings, these days women and girls might don a thobe when performing folk dances at festivities such as national day celebrations.

Women in one Iraqi family recall how the custom of wearing thobes changed over four generations. Nawal Barbuti grew up in Iraq in the 1950s and ’60s, and she recalls that her grandmother’s generation wore the hashmi and the sayah dress under plain black abayas when they went out. In her mother’s generation, women favored Western dress styles, and the only time they wore a hashmi was to put on a black one for a funeral. In the late 1970s, there was hashmi revival, led by the government-run Iraqi Fashion House. Barbuti’s daughter Sara remembers wearing a red hashmi made by a family friend when she attended henna parties as a child in the 1980s.

Flanked by mannequins displaying the manthur style, Mohamed Saleh runs Saleh for Zari in Bahrain. Manthur is popular all over the region, and it is distinguished by a smaller embroidery panel in front and embroidery motifs scattered throughout the garment.

One of the most active thobe-revival markets today, according to Saleh, is in Qatar. He flies the 280-kilometer roundtrip between Manama and Doha at least once a week. But now, instead of a suitcase full of samples, he packs maybe just one or two thobes, a pair of mobile phones and a laptop. More and more sales, he says, are coming through his posts on Instagram, and he takes orders over WhatsApp.

One of his Qatari customers, he says, recently ordered several dozen manthur-style thobes of tulle in a bouquet of colors for the guests at her daughter’s wedding, and she of course encouraged them to wear the thobes at the party.

Artist Hend al-Mansour recalls how growing up in al-Hasa Oasis in Saudi Arabia, she would watch her aunt make and embroider thobes on her sewing machine. Now an artist living in the us, al-Mansour maintains her family ties and says young women in al-Hasa have returned green and red thobes, after years of fashion neglect, to the henna-party tradition. Al-Mansour says she herself wore a green one at her own wedding in 2002.

It’s a key part of her identity, says al-Mansour, who says she always keeps at least one in her closet. She recalls that while studying at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design she once made a full-size self-portrait—dressed in her thobe.

Five details of the many hand-embroidered motifs used on the garments often worn with the thobe, sirwal (gathered pantaloons) and dira`ah (long-sleeved gowns), drawn from displays in the Bahrain National Museum.

Laila al-Bassam teaches a course in traditional Saudi women’s dress at Riyadh’s Princess Noura University in which her students cut and sew five traditional garments. A longtime collector of these garments and a fashion designer herself, al-Bassam wrote a book whose Arabic title translates to Traditional Inheritance of Women’s Clothing in Najd, about the women’s dress of her hometown of ‘Unayzah.

“People wear these gowns in Ramadan now. It is very important to attend evenings in Ramadan in this kind of dress—but new ones, not exactly the old ones,” she says. “People here are really interested in this kind of fashion. It looks nice and it gives the effect of the old gowns, with the cut lines and embroidery.

“For myself, sometimes I copy the old, but I use new colors since the traditional style was usually black. So I make a mutaffat [striped]-style thobe, but in all colors—red, fuscia, green—any colors I can find.”

Writing about late 20th-century traditions in the uae, Reem El-Mutwalli authored a beautifully illustrated, bilingual book, Sultani: Traditions Renewed. For her own part, she says that although she follows fashion in the uae, where she has lived for many years, she cherishes the thobes she inherited from her grandmother in Iraq, where she herself was born. Accordingly, she calls her own thobes hashmis, and she wears them for special occasions.

In the Emirates, she says, women still wear the thobe at festivities, religious holidays and wedding celebrations, and that “nowadays we have a tradition during Ramadan of people dressing up in Arab Islamic style … so they look for the thobe al-nashal and the new contemporary versions [from] new designers,” she notes.

“They interchange between the traditional, the new versions and the metamorphosed versions of those. It runs in circles. Every few years you start having a return to that style, then going away from it and then coming back.”

You may also be interested in...

Nakshi Kantha: Tradition and Identity in Every Stitch

Arts

History

A traditional form of quilting in Bangladesh in which women embroider family history, love and memory into the fabric is blanketing markets locally and beyond.

Sara Domingos Investigates the Threads of Portugal’s Multilayered Heritage

Arts

In a cavernous studio beneath the Church of Saint Mary Magdalene, just a 15-minute walk from Lisbon’s Moorish Quarter, a cross-cultural interplay between the Portuguese city’s old Islamic and modern-day traditions manifests under the steady hands of Sara Domingos.

Silk Roads Exhibition Invites Viewers on Journeys of People, Objects and Ideas

Arts

An evocative soundscape envelops visitors as they enter the Silk Roads exhibition at the British Museum in London. Huge screens along one wall project images of landscapes and oceans, while visitors are invited to experience the scents of balsam, musk and incense contained in boxes around the exhibition.