On September 27, 1822, 31-year-old Egyptologist and philologist Jean-François Champollion stood before the members of Paris’s Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres and proclaimed that “after 10 years of intensive research … we can finally read the ancient monuments.”

I have … a firm basis on which to assign a grammar and a dictionary for these inscriptions used on a large number of monuments and whose interpretation will shed so much light on the history of Egypt,” Champollion informed his astonished audience.

Among those seated was Champollion’s chief rival and former collaborator, English physician and polymath Thomas Young. Since parting company in 1815, Young and Champollion had engaged in a contentious race to unlock the tantalizing secrets of the hieroglyphs.

Yet the two linguists were competing in a race that had already been run by medieval Arab scholars and scientists. While Champollion’s discoveries were groundbreaking at the Académie, previous European scholars were familiar with a 10th-century Arabic work attributed to an alchemist and historian from what is now Iraq, Ibn Wahshiyya al-Nabati, titled Kitab Shauq al-Mustaham fi Ma‘irfat Rumuz al-Aqlam (Ancient Alphabets and Hieroglyphic Characters Explained). In it, he exhorted, “Learn then, O reader! The secrets, mysteries and treasures of the hieroglyphics, not to be found and not to be discovered anywhere else … now lo! These treasures are laid open for thy enjoyment.”

Though pharaonic Egypt is one of history’s most enduringly popular periods among scholars, study of medieval Arabic texts concerning what we now call “Egyptology”—including the hieroglyphs—remains sparse. This attracted El-Daly’s curiosity.

El-Daly’s research raises intriguing questions: Were 19th-century Western scholars indeed the first to unveil the “secrets” of the hieroglyphs, and to what extent were hieroglyphs already known to their medieval Arab counterparts?

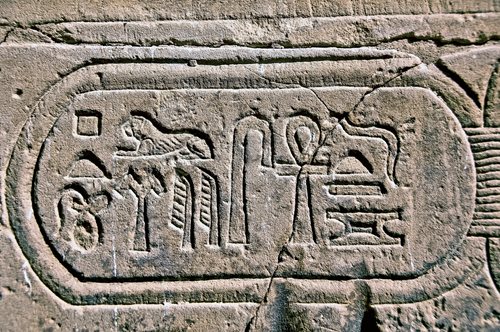

The earliest hieroglyphs, dating to the end of the fourth millennium bce, appear on pottery and ivory plaques from tombs. The last known inscriptions date from 394 ce, at the Temple of Isis on the island of Philae in southern Egypt. “But the glory of hieroglyphs,” observed the late Michael Rice, author of Egypt’s Legacy: The Archetypes of Western Civilization: 3000 to 30 bce, evolved during the Old Kingdom (2686–2181 bce), achieving their highest level of development in the Middle Kingdom (2055–1650 bce). This was a monumental age when the walls of Egypt’s palaces, temples and tombs were awash in hieroglyphs rendered in the vibrant colors of the natural world: Nile blue, palm-frond green and the dusk-reddened sky of the western desert, where mummified pharaohs awaited their journeys into the afterlife.

“The beauty of the colouring of these intaglios no one can describe,” observed Florence Nightingale on her visit to the richly decorated tomb of Seti i in 1850. “How anyone who has time and liberty, and has once begun the study of hieroglyphics, can leave it til he has made out every symbol … I cannot conceive.”

[T]he wise men of Egypt … did not go through the whole business of letters, words, and sentences. Instead, in their sacred writings they drew signs, a separate sign for each idea, so as to express its whole meaning at once.

By this time, there were fewer and fewer native-born Egyptians who could read the hieroglyphs. As Egypt became increasingly Romanized after the fall of Cleopatra in the first century bce, hieroglyphs were gradually replaced by the Roman alphabet.

Still, what Plotinus and his classical predecessors did not grasp was that hieroglyphics are more than simple ideograms, that is, pictures representing concepts or ideas, much as a circle with a red bar across a smoldering cigarette indicates “No Smoking.” Rather, they build their meanings off three elements: logograms, representing words; phonograms, representing sounds or groups of sounds; and determinatives, marks or images placed at the end of a word to clarify its meaning.

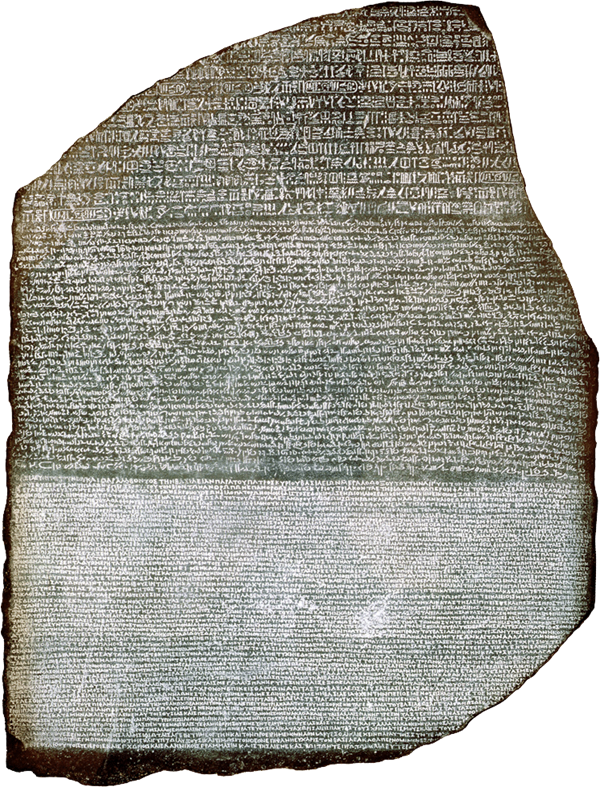

The key to Champollion’s understanding was his knowledge of Coptic, which is the linguistic descendent of the spoken Egyptian of the pharaonic era. Coptic uses Greek letters together with a handful of colloquial, or demotic, characters. Associating spoken Coptic with the written hieroglyphic script gave him his missing link. This was how Champollion deciphered the now-famous Rosetta Stone, a fragment of a second-century-bce stele inscribed with a royal decree issued by Ptolemy v. The inscribed decree was written in each of hieroglyphic, Demotic (Coptic’s grammatical cousin) and Greek. Champollion’s breakthrough came by comparing the scripts and realizing that the hieroglyphs were phonetic.

What Ibn Wahshiyya’s classical predecessors did not grasp was that hieroglyphics are more than simple ideograms, that is, pictures representing concepts or ideas.

“They wandered around, looking at the Pyramids, looking at the monuments, looking inside the beautifully decorated tombs, and if you are a scholarly person, you must have wondered, ‘How did they build them, what was their function?’” says El-Daly.

They also could not help but be intrigued by the hieroglyphs, and they speculated on their meanings. By inference, the first known Muslim scholar to pry into their mysteries was late eighth- and early ninth-century alchemist Jabir ibn Hayyan. Although nothing of his work on hieroglyphs is known to survive, we know of his interest through other, later alchemists who refer to it. Among them was his contemporary, Egyptian-born Dhul-Nun al-Misri. Al-Misri directed those interested in learning more about ancient alphabets to Ibn Hayyan’s book Solution of Secrets and Key of Treasures.

El-Daly notes another early scholar, Ayub ibn Maslama, also had “knowledge of deciphering the letters of the hieroglyphs.” This we know, he explains, through the writings of the 12th-century geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi, who had a deep interest in Egypt. Al-Idrisi recorded in his book Secrets of the Pyramids that during a visit in 831 to Egypt by Abbasid Caliph al-Mamun, Ibn Maslama “translated for Al-Ma’moun what was written on the Pyramids, the two obelisks of Heliopolis, a stela found in a village stable near Memphis, another stela from Memphis itself, [as well as writings found] in Bu Sir and Sammanud. Everything he translated is in a book called al-Tilasmat al-Kahiniya (Priestly Talismans).”

Sadly this last book, like Ibn Hayyan’s, is now lost. Yet texts attributed to al-Misri have survived, and they offer unique, insider perspectives on the composition of the hieroglyphs. A contemporary of Ibn Maslama, al-Misri spent most of his life living in or beside one of the temples at Akhmim in Upper Egypt, El-Daly points out. There, surrounded by hieroglyphs and Coptic-speaking priests, he would have been perfectly positioned to learn “the language of the walls of the temple, i.e., hieroglyphs,” El-Daly says.

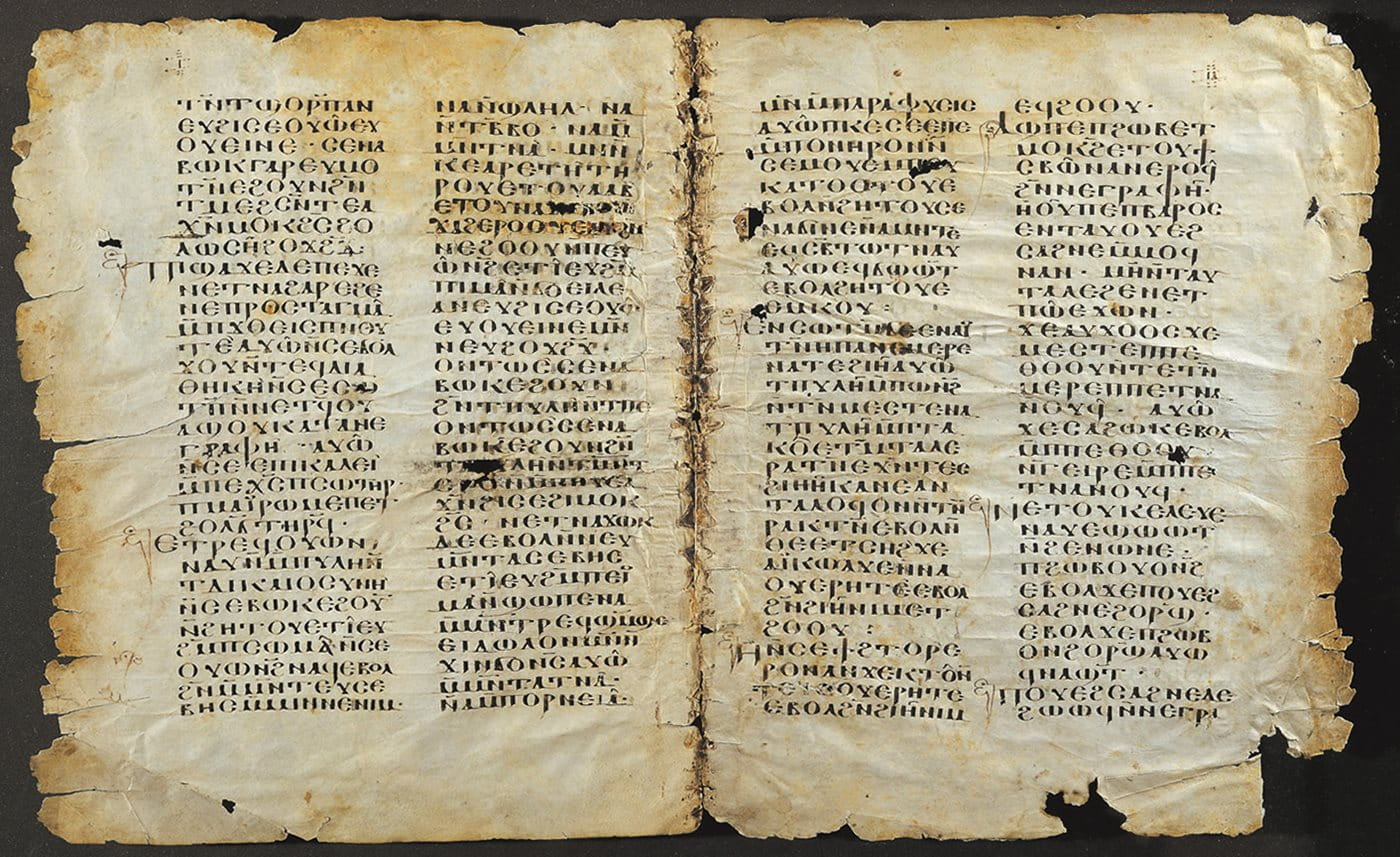

The closest linguistic descendent of Pharaonic Egyptian is Coptic Egyptian, which appears on this parchment manuscript from the eighth or ninth century. This script combines elements of Old Greek and Demotic characters derived from hieroglyphs. Ibn Wahshiyya, Kircher and Champollion, as well as others, knew this and used it to achieve their understandings of both Demotic and hieroglyphs.

This is more than pure speculation, he adds, because al-Misri himself indicated as much in his attributed al-Qasida fi al-San‘ah al-Karimah (Poem on the Noble Craft), in which he stated he was a student of the priests and was aware of the knowledge they possessed, still visible on the walls of temples. He also recorded that he made a connection between the spoken Coptic of his day and the ancient Egyptian language, and recognized that the hieroglyphs had phonetic value—the same connection Champollion would make 10 centuries later. He left behind a record of his research, Kitab Hall al-Rumuz (Book of Deciphering Symbols). Tellingly, al-Misri’s book included a table of Arabic letters and their Coptic equivalents, which proved a valuable resource for later medieval Muslim scholars who sought to translate the hieroglyphs.

It was no coincidence that these scholars practiced alchemy, which at that time constituted a broad field of pursuits. “Egypt was the epicenter of ancient wisdom, magic, alchemy, mysterious scripts and astrology,” notes Isabel Toral-Niehoff, a scholar of Arabic Occult Sciences at Germany’s University of Göttingen. “Whoever was interested in magic, astrology, mysterious alphabets, etc., in medieval Islam came automatically in contact with aegyptiaca or pseudo-aegyptiaca. This connection, harmonized with the popular perception of Egypt as the epitome of miracles, … inspired the everyday experience of inhabitants and visitors of Egypt.”

Ibn Wahshiyya’s achievement rested in distinguishing between hieroglyphic symbols that were phonetic and those that served as determinatives.

Foremost among these visitors was Ibn Wahshiyya al-Nabati. Born in the ninth century in Qusayn, near Kufa (now in Iraq), he was interested also in medicine, toxicology and agriculture.

His most important contribution is what El-Daly identifies as his tables of determinatives, the essential symbols that “determined” the meaning of words. For example, in an ancient Egyptian group of letters “p + r + t” can mean the infinitive of the verb “to go,” the winter season or the word for “fruit” or “seed”— depending on its accompanying determinative sign. If the scribe meant to communicate walking, running or movement, he added the determinative symbol of a pair of walking legs at the end of the word prt. A sun disc (a dot inside a circle) indicated the season, while a pellet symbol (a small circle) identified the agricultural product. Thus, without an understanding of the role of determinatives, Egyptian hieroglyphs remain hopelessly muddled. Ibn Wahshiyya’s achievement rested in pulling all these threads together, distinguishing between hieroglyphic symbols that were phonetic and those that pictographically served as determinatives.

El-Daly himself was uncertain about Ibn Wahshiyya’s claims until he compared the alchemist’s tables of determinatives to those in “Gardiner’s Sign List,” the modern, standard guide to interpreting the hieroglyphs, published in 1927 by renowned Egyptologist Sir Alain Gardiner.

“In every case I compared them, they were exactly the same,” said El-Daly.

“Even though the signs of [his] list are actual hieroglyphs, the values of the Arabic letters bear no relationship to the actual phonetic values of the hieroglyphs depicted,” she asserts.

Yet El-Daly defends Ibn Wahshiyya’s work by pointing out that like any language, hieroglyphic symbols changed over time. Those seen by the medieval alchemist during his sojourn in Egypt were likely from the Greco-Roman period, El-Daly says, and differed from earlier hieroglyphs. He also stresses that the number of hieroglyphs Ibn Wahshiyya correctly translated is not the issue: What matters is that he realized the hieroglyphs were phonetic and that determinatives governed their meaning. Considering that none of this began to dawn upon European scholars until the mid-17th century, El-Daly thinks Ibn Wahshiyya deserves more than passing credit for working out as many symbols as he did.

“Do you know how many letters Champollion started with? Three letters. So, good for Ibn Wahshiyya, who had at least nine right,” remarks El-Daly.

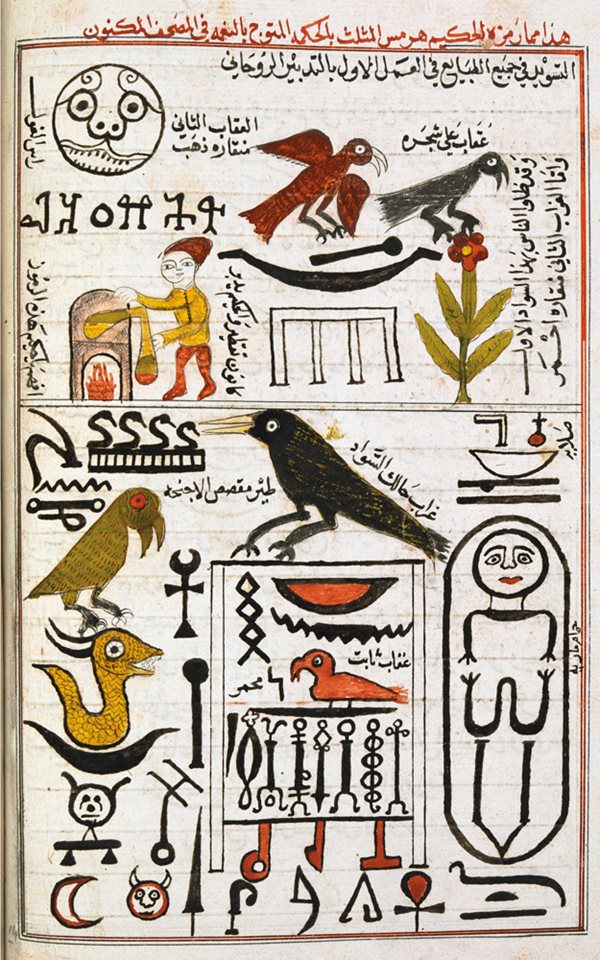

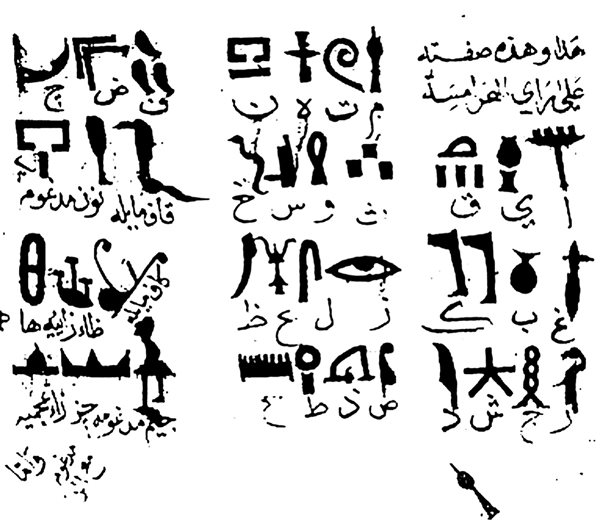

Later, Ibn Wahshiyya had his own followers. The 13th-century alchemist Abu al-Qasim al-Iraqi produced Kitab al-Aqalim al-Sab’ah (Book of the Seven Climes), a visually striking manuscript that includes the phonetic values of hieroglyphs (not always correctly) as well as colorful, at times fanciful, illustrations that combine hieroglyphs, Arabic and alchemical symbols.

In one such rendering, al-Iraqi apparently copied a now-missing stela dedicated to the 12th Dynasty (early second millennium bce) pharaoh Amenemhat ii. The top line of the illustration, written in Arabic, credits the content of the page to the “hidden book” of the mythological Hermes Trismegistus (Hermes of Triple Wisdom). Hermes was an amalgam of the Egyptian god Thoth and the Greek deity Hermes who, as a messenger of the gods, was associated with communication and the written word. Medieval Muslim alchemists equated him with the prophet Idris mentioned in the Qur’an (and in the Bible as Enoch), and they respected him as not only the first alchemist, but also the originator of the hieroglyphs as well as a source of ancient, hidden wisdom.

![Excerpts from Hammer’s translation of Ibn Wahshiyya’s ninth-century manuscript also show the Assyrian scholar’s phonetic and ideographic translations of hieroglyphic characters. These Ibn Wahshiyya and other Arab scholars regarded as <em>qalam al-hakim hermes al-akbar </em>(script of the great savant Hermes [Trismegistus]). Ibn Wahshiyya divided hieroglyphs into four categories: celestial objects; figures of animals, actions and affections; trees, plants and produce; and words and ideas connected to minerals—an analysis that shows his alchemist’s orientation.](https://prodcms.aramcoworld.com/-/media/aramco-world/articles/2017/arab-translators-of-egypt-s-hieroglyphs-images/image-8.jpg)

Nonetheless, the trails they blazed were picked up by Renaissance European scholars who believed that Arabic manuscripts on Egypt might offer clues to deciphering hieroglyphs. Among the most influential was a 17th-century German Jesuit priest, Athanasius Kircher. In his seminal work, Lingua Aegyptiaca Restituta (The Egyptian Language Restored), published in 1643, Kircher correctly hypothesized that the hieroglyphs recorded an earlier stage of Coptic and that the signs had phonetic values. His sources included Coptic grammars, translated from Arabic and Coptic-Arabic vocabularies brought back from the Middle East by contemporary Italian travelers. By El-Daly’s estimation, Kircher had access to some 40 medieval Arabic texts on ancient Egyptian culture, including Ibn Wahshiyya’s. Though the Jesuit only got one hieroglyph right, his contribution, too, pointed subsequent scholars in the right direction.

“Only with the work of Athanasius Kircher, in the mid-17th century, did scholars begin to think that hieroglyphs could represent sounds as well as ideas,” writes Brown University Egyptologist James P. Allen in Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. “It was not until the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, in 1799, that scholars were able make practical use of Kircher’s ideas.”

While some believe El-Daly overstates the importance of medieval Muslim scholarship on the hieroglyphs, and they are thus doubtful of its Egyptological value, El-Daly himself says that he never set out to unseat Champollion or credit medieval Muslim scholars with as deep an understanding of the hieroglyphs as the French savant or his successors. He merely wished to add to the conversation “over a thousand years of Arabic scholarship and inquiry” that modern Egyptology has largely overlooked.

You may also be interested in...

2024 Calendar

History

Making positive connections has been the mission of AramcoWorld since its first edition 75 years ago. In the words of former Aramco President Bill Moore in Volume I, No. 1: “We hope this publication will enable us to get better acquainted with ourselves.” In the same way each month, we hope this calender connects to some of the people and stories we have highlighted over the past 75 years.

Reflections on Connections

Arts

History

In 2024 AramcoWorld is marking 75 years of transcending cultural barriers. From its early days as an intra-company newsletter seeking to enrich understanding between employees in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, and the original Aramco headquarters in New York, it evolved into a full-blown magazine focused on engaging external audiences around the globe. This first in a series of anniversary articles follows the timeline of a publication whose bridge-building mission continues.

Reflections of Knowledge

History

Science & Nature

Part 3 of our series celebrating AramcoWorld’s 75th anniversary highlights the magazine’s emphasis on experts and institutions that push the boundaries of present-day knowledge while paying homage to historical figures and writings that paved their way.