Bahrain's Pearling Path

Written by Sylvia Smith

Photographs and video by Richard Duebel

It’s 9:30 on a Saturday morning, and already the usual crowd is building up outside Saffron, a café on Muharraq, the second-largest island in the archipelago of Bahrain. Locals and foreigners chat congenially while they wait for tables to open. Parents distract restless children by pointing out to them the 400-year-old date press sunk into the ground that extends under the café, visible through glass panels in the floor.

It’s a typical weekend rush at Saffron, one of the most successful of the restored and repurposed historic buildings on the island that was once the capital of Bahrain during its centuries of pearling prowess. It’s also a fine place to take on sustenance before setting out on the 3½-kilometer “Pearling Path” to view 17 restored historic buildings that celebrate Muharraq’s heritage—part of a string of local sites that in 2012 unesco placed on its World Heritage List.

The most popular meal, Kamber says, is the eight-dish, “full Bahraini” breakfast, which is served “in small pots all on one tray, tapas-style,” she tells a table of first-timers. And, she adds, “We can easily make it vegan.”

Among the offerings are sweet vermicelli cooked in rosewater, cardamom and saffron; beans slow-cooked in a spicy tomato sauce; thin bread brushed with an anchovy-like fish paste; a vegetarian kebab; and a subtly spiced potato dish served with milk tea. All are enhanced by music playlists Kamber has compiled from childhood memories of hearing folk songs hauntingly sung by local artists. “Youngsters often ask me if they can download,” she says with a laugh.

“We enjoy eating here because of the atmosphere,” says a young regular named Abdulla, who is tucking into a “full Bahraini” breakfast. “And the food tastes great!"

The heavy, 100-year-old wooden door at Saffron’s entrance is another relic of the past, and it is a portal to the future for Muharraq—a link between the island’s rich history and its newfound modern identity as a culture hub.

In the early 1930s, Bahrain had to recalibrate its economy to account for both the discovery of oil and the arrival, from Japan, of the cultured pearl. Together these collapsed the old pearling culture, which had developed over millennia and provided prosperity, social cohesion and identity. Bahrainis—from ship captains to pearl divers, chandlers to knife sharpeners—had to leave pearling behind as Bahrain’s capital moved a couple kilometers west to Manama.

Shaikha Mai’s effort was, she says, born out of her respect for Shaikh Ebrahim, her grandfather, and her determination to keep his memory alive. Born in the mid-19th century, he was recognized in the region as a man with a thirst for knowledge and debate who attracted the best minds to his majlis, or salon, until his death in 1933.

Among his guests were Farida Mohammed Saleh Khunji, one of Bahrain’s most prominent religious and literary intellects; Yusuf bin Ahmed Kanoo, a leading businessman in the Gulf region; Hafez Wahbah, an educator and author who moved to Riyadh and served as Saudi Arabia’s ambassador to Great Britain during World War ii; and Louis P. Dame, md, a physician at the American Mission Hospital in Bahrain who was known for his work in the region.

The center, Shaikha Mai explains, was never planned in isolation. Her vision was to build on—not over—Muharraq’s pearling past.

In the case of Shaikh Ebrahim’s house, architects, engineers, planners and designers, all mainly from the Arab world, turned the house—for the second time around—into a new kind of magnet for intelligentsia, one featuring a 300-seat auditorium with a research library upstairs. On its walls, photographs portray the hundreds of personalities who have lectured, read poetry, performed music and provided other cultural stimulation since the building’s reopening 15 years ago, including Zahi Hawass, Egypt’s former antiquities minister, and Zeinab Badawi, a British television and radio journalist who was born in the Sudan.

This year’s anniversary provided a chance to assess the area’s changes, and the baca celebrated and promoted it with “15/15,” an art exhibition spread among 15 restored houses. Hala Al Khalifa, director of Culture and Arts at the baca and an artist herself, stepped back in time with an installation called “Light” that projected, on the center’s façade, the names in Arabic of leading figures who had visited the house during Sheikh Ebrahim’s time. “I wanted to highlight the legacy of my great-grandfather on the spot where he met many forward-thinking personalities from countries throughout the world,” she explains.

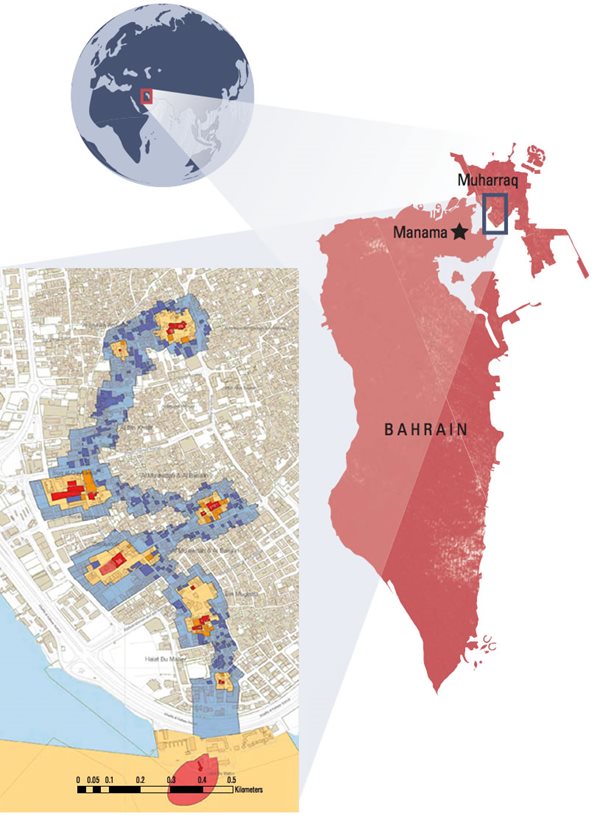

Visitors to the three-month-long celebration could walk along the new, winding, pedestrian-only “Pearling Path,” which zigs, zags and wiggles through the southwest part of Muharraq. Officially it starts northbound from Bu Maher Fort on the island’s southern tip, which was the historic departure point for pearl divers as they left for a four-month season every summer. Opalescent, pearl-round streetlights guide visitors from a simple pearl diver’s house, Bayt al-Ghus (from ghawwas, Arabic for diver)—now a small museum displaying the basic tools of the trade (a nose clip, a knife and a string bag for the oysters)—to the grand houses of the pearl merchants, several now endowed with new purpose.

Other stops include a coffee shop where pearl traders used to chat and play carom, a traditional board game, and the Mohammed bin Faris House for the local, traditional sawt music, where every Friday night there is a free concert. The standard of craftsmanship in all the buildings makes the restorations stand out, says Sophia Delobette, a local guide. “There is imagination in the way each building has been envisaged to suit another era,” she says. “What I really like is the attention to detail and the meticulous finish.”

One of the largest and most elaborate buildings on the trail, the two-story Bin Matar House, reflects the importance of that family in the pearl business, explains its director, Melissa Enders-Bhattia. “This magnificent early 20th-century house was constructed as a family home,” she says. “Now that it’s been fully restored, we have an art gallery space for temporary exhibitions.”

It was here that, for the “15/15” event, photographer and artist Camille Zakharia showed his series of black-and-white images of Muharraq’s narrow streets, “Stories from the Alley,” which use photographs, collage and calligraphy. “I have recorded the rich, traditional Bahraini architecture,” Zakharia says. “I am hoping to encourage people to appreciate and preserve their architectural heritage, rather than just being part of this globalized world.”

Shaikha Mai, he says, has been “a force behind all these traditional houses here to ensure they remain standing, and you can see the quality of restoration that has taken place to regain their beauty.” The costs of the restorations have been borne by both public and private sectors through Shaikha Mai’s sponsorship initiative called “Investing in Culture,” which brings Bahrain’s cultural sector into partnership with its banking and financial institutions.

As more houses were restored, the Ministry of Culture took the project further, winning unesco approval for the 17 Muharraq buildings, three oyster beds that lie north of the island, part of the shoreline and Bu Maher Fort to all be placed on the World Heritage List. The agency’s report called the places “the last remaining complete example of the cultural tradition of pearling and the wealth it generated ... from the second century to the 1930s,” adding that collectively they represent an “outstanding example” of how human interaction with the environment shaped the economy and society. “We are proud that this final expression of the pearling industry has been recognized internationally,” Shaikha Mai says.

The listing has become the springboard for the restoration of the entire old city of Muharraq, which is now one of the best-preserved historic cities in the Gulf region, with another 600-odd buildings to be restored.

According to Noura Al-Sayegh, a Lebanese architect who works closely with Shaikha Mai on the renovations, the importance of the creation of the Pearling Path goes beyond rebuilding. “We hope to improve the economy by creating cultural tourism as well as making Muharraq a more pleasant place in which to live,” she says.

Already, passengers from cruise liners that dock in Bahrain are taken to the shoreline near Bu Maher Fort. At one of the stops on the Pearling Path, Kurar House, they visit a suite of rooms displaying traditional clothes sporting gold trimming still made there by a complex hand-weaving process. As she watches four women entwining the multiple threads, British tourist Anne Scott comments, “It looks a bit like the cat’s cradles we used to make as children, only far more complicated. The results are better too!”

The finished golden bands that emerge after the interchange of threads are put on sale as decorative edging for clothing. At around $25 a meter, it may be expensive, but Scott thinks it is a great value. “I have an evening dress that I can stitch this onto,” she says. “I think it will really add something exotic.”

As the group of visitors makes its way along one of the narrow lanes, members enter a small guesthouse that accommodates speakers, poets and singers who appear at the Shaikh Ebrahim Center. In its previous incarnation, the restored house was home for a merchant who traded in ropes and wood used to construct dhows, such as those that carried pearl divers, explains Delobette.

Next stop is Press House, the former dwelling of Abdullah Al Zayed, founder, in 1939, of the first weekly newspaper in Bahrain and the Gulf region. His 100-year-old home has been reborn as a place of both architectural and literary illumination dedicated to preserving Bahrain’s press heritage with displays and an archive of the country’s early journalism. Al Zayed’s typewriter, official letters written on it in English by the multilingual owner, his bed, photographs of the man himself, and back copies of the newspaper that ran until 1944, shortly before his death, all give texture and context to the restoration.

From one of its upstairs windows, a contemporary addition to the neighborhood is brightly visible: a wall filled with the colorful calligraffiti of French Tunisian artist eL Seed. It contrasts dramatically with its immediate neighbors, the understated Siyadi House, whose plain exterior belies an intricate interior, and the adjacent Siyadi Mosque, built by Ahmed bin Jasim Siyadi, a 19th-century pearl merchant, about the same time as the house. The mosque, too, has been restored for community use, and its 10-meter minaret will not be overshadowed anytime soon: Zoning laws now limit buildings in the historic area to two stories.

Not far away, Hamad Busaad, a young entrepreneur, runs his design business and Busaad Art Gallery in the house that belonged to his great-grandfather and where his father, now an artist, was born. “You need a good architect to retain the authenticity, the traditional look and feel, of an old house like this,” he says. “The restoration’s been quite a challenge. The building became a cold store, then a corner shop, after my family moved out. My father decided to get the house back after we had driven past one day. Seeing it made my dad decide to turn it into an art gallery.”

After all the quiet good taste of the earlier restorations, confidence has grown, and some of the most recent restorations and new buildings are near-riots of color and design innovation. Dar Muharraq, for example, has tangerine-colored walls and an outer “curtain” of metal chains that rises whenever dances are performed there and falls again afterward to close off the building. The new Al-Khalifiyah Library is entirely contemporary architecture: With a bronze sheen and gradually cantilevered upper floors, it’s like an inverted ziggurat—a design that takes creative advantage of a small plot of land.

One can only imagine the astonishment—and pride—that Muharraq’s divers and merchants might feel now if only they could see their old neighborhood again, a bit like old pearls, once forgotten but rediscovered, buffed and set on a string as a new national treasure.

About the Author

Richard Duebel

Richard Duebel is a filmmaker, photographer and art director who has been working in North Africa and the Middle East for more than 20 years. His interests lie in culture, the environment and the applied arts.

Sylvia Smith

Sylvia Smith makes radio and television programs from the Arab world as well as reports from Europe and elsewhere that explore connections with North Africa and the Middle East.

You may also be interested in...

Tima Abid's Fashion Forward

Saudi couture designer Tima Abid merges contemporary fashion with Arabian heritage. Her glamorous collections are earning recognition from Paris to Riyadh. With her latest designs Abid not only is making her mark on the runways, she is redefining bold elegance amid changing times in the Arabian Gulf.

Soaring Perspective on the Global Food Chain

Food

In his latest book, Feed the Planet, photographer George Steinmetz visits nearly every corner of the world to record diverse yet linked aspects of the global food chain—including aquaculture.

Cracked Wheat and Tomato Kibbeh Recipe

Food

Simply cooked line-caught fish with this beautiful tomato kibbeh. I don't know how you could top it.