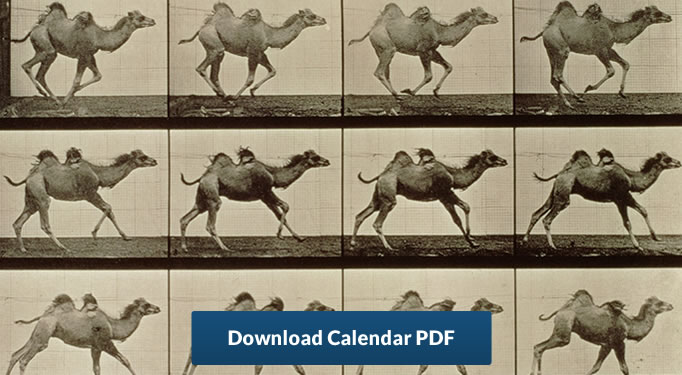

2019 Gregorian-Hijri Calendar – Camel

- Science & Nature

Introduction by Peter Harrigan

“DO THEY NOT LOOK AT THE CAMELS,

HOW THEY ARE MADE?

AND AT THE SKY, HOW IT IS RAISED?”

—QUR'AN 88:17

(ENGLISH BY YUSUF ALI)

Ever since camels gradually fell into the service of people in the arid lands of Arabia, Africa and Asia about 4,000 years ago, they have evoked wonderment. Their domestication, late compared with other species, had a profound influence on the societies of these vast territories through the exchange of ideas and the interaction of languages as well as culture both intangible and material. They provided, for the first time, an effective means for long-distance overland travel for merchants and the seasonal migrations of tribes. By the coming of Islam in the seventh century ce, a complex network of trade and pilgrimage routes had developed that connected the far reaches of the known world.

The consequences were as significant then as those experienced more recently with the advent of the telegraph, the internal combustion engine and, most recently, the Internet.

There are two domesticated camel species, and they can be identified with ease. The one-humped species numbers some 27 million worldwide, making it by far the most populous. It has also the greatest variety of breeds, numbering at least 90. Known as the dromedary (Camelus dromedarius), it inhabits the hot desert lands of the Arabian Peninsula, Levant, North Africa and the Horn of Africa. The two-humped species, the Bactrian (Camelus bactrianus), numbers around three million. It populates the colder deserts and steppes of Central Asia with 14 recognized breeds.

The wild predecessors of both the dromedary and the Bactrian camels are extinct. Archeologists and geneticists are now using ever-more-sophisticated technologies to unpick often scant and elusive evidence of the story of its evolutionary migration, domestication and ancestral species extinctions. Today the only surviving wild species of camel is the two-humped Camelus ferus, whose critically endangered population of about 1,000 lives mainly in the Gobi Desert.

Studies of all three species continue to reveal wonders of adaptation, characteristics and potential. Wild camels, for example, can drink slush with more salt in it than seawater. (They also appear to have been unaffected by decades of nuclear tests conducted in their now-protected habitat.) Milk from camels contains an insulin-like molecule, and it is replete with antibodies and enzymes. It lowers cholesterol in humans, and it can be consumed by people with allergies to cow’s milk. Studies are currently examining camel-milk immunoglobulins for cancer-fighting potential.

The camel’s environmental adaptations include blood-temperature range not unlike that of reptiles, and this helps camels endure extreme temperatures. In addition, as dehydration thickens a camel’s blood, its red cells elongate, which enables them to flow continuously. To help the camel hold water, the cells can expand to more than three times their original volume—far more than those of any other mammal. (This is what allows a camel to drink up to 120 liters in 10 minutes—more capacity than the fuel tank of a large utility vehicle, and not much more time in “refueling.”) As for its range capabilities, a watered camel can travel, with time for grazing, up to a week or more without water, and it can cover more than 600 kilometers.

The rider’s experience is also unique. Explorer and writer Eldon Rutter traveled on camelback in western and northern Arabia in 1926. During hot months, desert travel was often best during the cooler hours of darkness, and Rutter describes the mesmerizing experience with the patient camels pacing forward until dawn. “It seems to the rider borne at such a height aloft, that he is silently gliding or swimming over a yielding unstable surface,” he wrote in his acclaimed book, The Holy Cities of Arabia.

In contrast, much other Western literature has stereotyped dromedaries as either whimsical or aggressive and ill-tempered, whereas anyone who has come to know and work with them invariably regards them as intelligent, sociable and gentle.

These characteristics and qualities of the dromedary have been deeply known in Arab lands for thousands of years, where camels have been a major motif in Arabic poetry, stories, vocabulary, metaphors, proverbs and humor. Camels literally enabled the transmission of an oral tradition. Traditional poems often include a description and elaborate panegyric that describes the fine mount that brings the poet or storyteller to audiences far and wide.

Today the dromedary is increasingly celebrated throughout the region for this cultural legacy, and for providing such a rich, productive and symbiotic relationship with its herders, breeders and keepers.

Globally, the camel population today accounts for fewer than one percent of domes- ticated herbivores. (Cows and cattle number two billion.) It is in the arid lands of Africa—and particularly in the Horn of Africa—that camel populations are highest and rising, as they are bred and tended as valuable, sustainable sources of food and materials: Estimates cite as many as 20 million, or roughly 80 percent of the dromedary population worldwide. The Arabian Peninsula has a dromedary population of around 1.5 million, and scientists in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are spearheading a growing field of research.

With its adaptability highly suited to face today’s emerging challenges of climate change, says Bernard Faye, a camel expert with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, camels “represent a fabulous biological model for scientists from different disciplines.” He argues that the camel’s place in the world deserves to be re-evaluated in light of trends and potential, including the qualities of their milk and meat, as well the promise of new derivative products. Little wonder, Faye contends, that no other domesticated animal has offered humans so much utility, pleasure and value.

About the Author

Paul Lunde

The late Paul Lunde authored more than 60 articles for AramcoWorld. He was a senior research associate with the Civilizations in Contact Project at Cambridge University and also co-author, with Caroline Stone, of Ibn Fadlan and the Land of Darkness: Arab Travellers in the Far North (Penguin, 2012).

Peter Harrigan

Peter Harrigan is a contributing editor and writer for Aramco World. As founder and editorial director of Medina Publishing, he has authored books on Riyadh and Diriyah. He is also commissioning editor for Arabian Publishing whose recent titles include Across Arabia: Three Weeks in 1937 by Geraldine Rendel.

You may also be interested in...

Reflections of Knowledge

History

Science & Nature

Part 3 of our series celebrating AramcoWorld’s 75th anniversary highlights the magazine’s emphasis on experts and institutions that push the boundaries of present-day knowledge while paying homage to historical figures and writings that paved their way.

Reviving Eden

History

Science & Nature

Until the 1990s, the reed marshes of Iraq were Eurasia's most extensive wetlands, with a unique ecology that supported the Marsh Arabs' distinctive way of life. Then the marshes were drained and the people scattered. Azzam of Alwash, the emigré son of an Iraqi hydrologist, now works with international aid groups and Iraqi authorities to restore the desiccated marshlands. Reeds are sprouting, birds and fish are returning-and so are people. "A 7000-year-old culture doesn't die in a decade, he says.

Jute, The Future’s Golden Fiber

Arts

Science & Nature

Jute grows in tropical wetlands worldwide but nowhere as organic and plentiful as the deltas of Bangladesh and India, where its golden-hued fibers are inspiring a new generation of biodegradable products from carpets to car seats, clothing to “bioplastic” grocery bags.