The Ottoman Carpets of Transylvania

Written by Louis Werner

Photographed by Matthieu Paley

Its central plateau open only to the Great Hungarian Plain to its west, Transylvania could be likened, on a geographical scale, to a walled city: To get there from any other direction, one must cross the high passes and navigate the labyrinthine valleys of the Carpathian Mountains. Perhaps it is this relative inaccessibility that lent Transylvania—literally “beyond the woods”—a reputation as a land of mysteries both romantic and real. It is famously the haunt of the fictional 19th-century Count Dracula, as well as, infamously, that of the factual 15th-century Prince Vlad Ţepeş (the Impaler). More curiously, even surprisingly, this region of north-central Romania is home to the world’s finest collection 16th- and 17th-century Ottoman carpets—some 400 of them.

Inhabited in antiquity by Dacians, the region had long been a prize contested by outsiders. Romans, Hungarians and Turks were the most powerful players, even if often from a remove. Romans left behind their Latin-based language, Hungarian kings sent their princes to rule in their stead, and the Turks collected tribute for protection and nearly complete internal autonomy. German Saxons from the southern Low Countries and Rhineland arrived in the 12th century at Hungarian invitation as a population buffer against inruding tribes from the east.

Instead of serving as Hungary’s buffer, however, Transylvania ended up a few centuries later serving as an Ottoman vassal. A 16th-century miniature captures the relationship as Hungarian King John ii Sigismund Zápolya kneels in fealty before Ottoman Sultan Suleiman (the Magnificent) in 1556. This would have been the heyday of Transylvanian Turkophilia, as reflected in the carpet collections of today. Although the demand for Ottoman carpets appears to have dampened by the early 18th century, when the Hapsburgs took control of the region and several Anatolian manufacturers closed, it endured through the early 19th century.

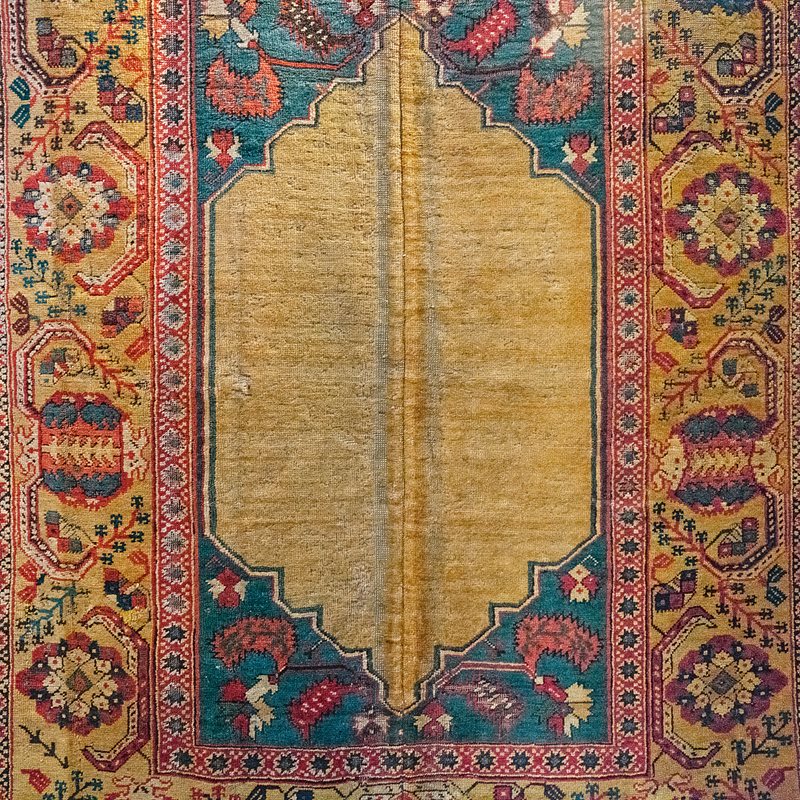

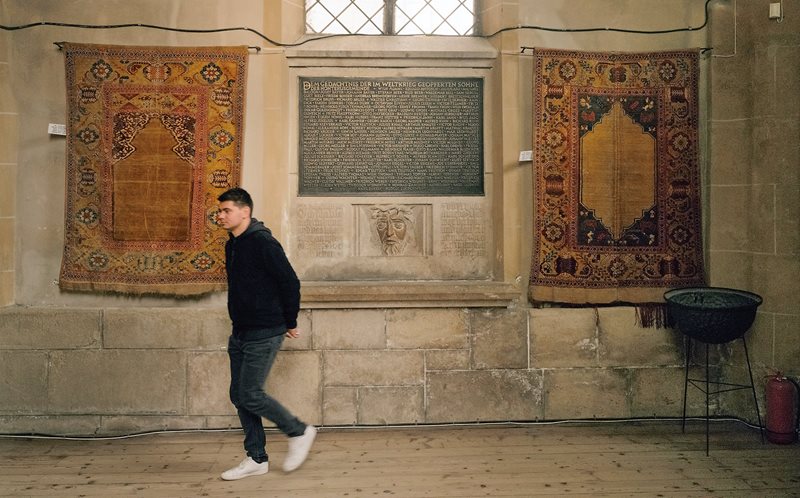

Among the wares were carpets. A Braşov customs register from 1503 recorded that 500 carpets passed through the town in that year. While Western Europeans were accustomed to placing carpets under foot, Transylvanians often used their carpets to adorn walls—nowhere more than in churches, where they were also frequently placed on pew fronts. There was reason for this: The Reformation came to Transylvania in the late 16th century. Its reformers whitewashed or destroyed Catholic frescoes, some dating from the 14th century, while the new Lutheranism did away entirely with figurative images and icons inside its places of worship. In their places, for decoration, they hung Ottoman rugs, many of prayer niche or arabesque designs, including distinctive white-background designs known as Selendis, after the Anatolian village of their manufacture.

Indeed, as art historian Agnes Balint-Ziegler pointed out, Ottoman carpets were a means by which a church “was stripped of the everydayness and imbued with a sacred character.” In this essentially public setting, Ottoman carpets donated by artisan guilds became equivalent to corporate status symbols, and those given by patrician families became a similar “means of private posturing.”

Bucharest’s National Museum captures well Romania’s multiethnic society at the time. There hang portraits of men with such titles as serdarul, or cavalry officer, a word derived from Persian via the Ottoman language; negustorul, or merchant, the name taken from Latin; and voievodul, or prince, this one from Old Church Slavonic. (For each, the Romanian suffix –ul, denotes a definite article, just as the name Dracula, from drac, means the devil.)

“In the church itself,” Gerard observed further, “hang some of the most exquisite Turkish carpets I have ever seen—such tender idyllic blue-green tints, such gloomy passionate reds, such pensive amber shades, as to render distracted with envy any amateur of antique fabrics.” Unfortunately, Gerald continued, these masterpieces were not “purchaseable for even the untold sums of heavy gold.”

Awestruck by the value and beauty of the carpets, Gerard wrote, some foreigners coveted them, yet their longings were in vain, for they were not for sale. “There was ein verrückter Engländer (a mad Englishman) here some years ago,” a churchwarden informed Gerard, “who would have given any price for the pale-blue one up yonder, and he remained here a whole month merely to be able to see it every day; but he had to go away empty handed at last, for these carpets are the property of the church, and not even the bishop himself has power to dispose of them.”

Not until 1898 were the rugs catalogued, and Romania’s 50-year period of communism further isolated them from scholars and enthusiasts. Only recently has an Italy-based Romanian independent scholar named Stefano Ionescu taken on the task of cataloguing, protecting, replicating as necessary and generally defending the carpets as one of Transylvania’s most beautiful artistic treasures, one that should stay in its historic place.

Ionescu, along with a Lutheran church administrator named Frank Ziegler and a handful of pastors in nearby towns, work as the carpets’ foremost champions. Ionescu calls the survival of these carpets a “fascinating intercultural phenomenon” and attributes their number to more than mere trade—not just in carpets, but also tenting, blankets, towels and fine clothing. (Local Hungarian nobles and urban Saxons, with Greeks and Bulgarians, were among the first Europeans to adopt articles of Eastern dress.)

Ionescu largely credits the religious tolerance of Transylvanians to explain the presence of the rugs’ frequent Islamic symbolism in a Christian setting, noting also the practical role that carpets play in everyday life—as a kind of bridge walked across, whether from one side of the room to another or from one culture to another. German Saxons certainly saw them in almost entirely secular, commodified terms—as prestige items—as painter Robert Wellmann showed in “The Adornment of a Saxon Bride,” an early 20th-century painting that shows, draped on a table beside a young woman being dressed, a Selendi “bird” carpet.

Similarly, it was not uncommon for 19th- and 20th-century Romanian painters to feature Ottoman carpets in their interior scenes. Nicolae Grant, whose English father was a diplomat and rug merchant, studied under the famous French orientalist painter Jean-Léon Gérôme in Paris. Modernist Gheorghe Petraşcu painted Transylvanian rooms in the style of Henri Matisse’s Moroccan tableaux, strewn with patterned textiles and upholsteries.

Ziegler notes that for some time it was a Transylvanian tradition to honor visiting dignitaries with gifts of carpets from the municipal guilds. In the 17th century alone, an estimated 1,000 carpets were given away.

Among Ziegler’s favorites, is a Lotto—so called after Lorenzo Lotto, an Italian painter who favored this style in his paintings. “Red, with yellow branches, and a narrow border, it represents 100 percent our uninterrupted heritage here,” he says. “It was never bought or sold again once it was given to the church, possibly after a funeral when the casket of the donor’s relative rested on it at the altar, or maybe it had dressed the church for a wedding or baptism. In any case, it transmits the value of past generations to all of us living today.

“We are not as much interested in holding copies as we are in maintaining the originals. Each bit of missing pile or stain speaks of our story too,” Ziegler adds. Some carpets have donation inscriptions written on the borders in black ink, “so we know the names and dates of the carpet’s donor.” For example, an early-17th-century prayer rug given to the church in Sibiu is noted with the date 1720 and “D. Mays.” Still vividly hued, a late-17th-century double-niche carpet was given to the church in Ghimbav in 1706 by Hannes Merglers. And more.

St. Margaret’s still holds the most exquisite of the collections, including four Holbeins and an Ottoman çintamani design marked by its tiger stripes: three dots and a squiggly line, lightheartedly translated into German as katzenpfoten (cat’s paw). The collection also comprises those with vogelkopf, a “bird-head” pattern, as the name implies. A replica carpet with an animal motif woven a few years ago in the Anatolian town of Konia, based on a 1930s photograph of a now-lost carpet, hangs next to a 16th-century Holbein fragment that first hung in a nearby church in Băgaciu; also there is a 17th-century, fully intact Lotto from Agârbiciu.

Such esteem goes a long way toward explaining why Teodor Tuduc, one of history’s greatest rug forgers (to the extent that carpet buyers often call any kind of fake “a Tuduc”), who worked in Braşov between the two world wars, chose to make and sell hundreds of fake Transylvanians before trying his hand at faking Persian, Caucasian and even Spanish carpets. As a result, there are still many unrecognized Tuducs in the market, and even some of those known for what they really are have become collector’s items in their own right.

An Ottoman fatwa dating from 1610 may help solve another mystery about Transylvanian carpets: Why are there among them so many “double-niche” carpets? These are carpets in the style of a traditional Islamic prayer rug, in which a pointed center field, designed after the Islamic mihrab that, in a mosque, points the direction of prayer. The double-niche carpets, however, show two points to the center field, as if the mihrab has two directions. This is no small question: According to a recent worldwide inventory, among 17th-century Ottoman carpets, 337 are double-niche designs, most in collections outside Turkey, and many in Transylvanian churches.

Ionescu believes there may be a connection between this and the 1610 edict by Ottoman Sultan Ahmad i that forbade the export of carpets with specifically religious patterns to Europe: By adding the mihrab’s mirror image on the opposite side, a carpet woven for export could not be considered—strictly speaking—a prayer rug.

At some point in Transylvania, one encounters Dracula. The northern town of Bistriţa figures in the first chapter of Bram Stoker’s novel. Protagonist Jonathan Harker heads there and, as he says in the novel’s opening, “The impression I had was that we were leaving the West and entering the East.” After spending a troubled night, “I did not sleep well though my bed was comfortable enough…. There was a dog howling all night under my window, which may have had something to do with it; or it may have been the paprika.”

It is odd indeed that Stoker, giving voice to Harker, should blame his insomnia on paprika. The Ottomans introduced the dried and powdered New World pepper spice to eastern Europe in the 16th century—just about the same time that the first Ottoman carpets arrived in Transylvania. From a purely culinary point of view, Harker might as easily have blamed other Romanian staple foods and beverages with names borrowed from the Turks—ciorbă, or soup; ceai, or tea; and covrig, a pretzel.

Bistriţa also provides its own tale, this a cautionary one on the nexus of community and patrimony, as told by Hans Dieter Krauss, the ebullient pastor of the town square’s grand gothic church. Pastor Krauss is trying hard to keep his flock intact despite its dwindling numbers in the latter years of the 20th century—first from the depredations of war, then communism and finally the call from the Federal Republic of Germany for ethnic Germans to return to the homeland. The 1910 census recorded 12,000 Germans in town, but that dropped to 5,000 in 1940, and by 1996 there were only 223 counted. (Since the fall of communism, some 1.5 million Germans have left Romania, leaving behind a national total of 36,000.)

Krauss, however, mourns more than the loss of community. In 1944, fearing the arrival of the Soviet Red Army, the town’s Saxons took 53 fine Ottoman carpets from the church for safekeeping in Germany, where they remain today in the Nuremberg Museum. Now he wants them back “because they are ours,” he says simply, “and they belong to their home parish.” He cites the principle of national patrimony as well as the basic property rights of Romania’s Lutheran Church and its Saxon culture.

Because Krauss stayed put when so many of his fellow ethnic Germans left, he feels a personal claim for their return. In the interim, Ionescu and others are arranging for authentic facsimiles to be made in the Sultanhanı weaving center and to donate to Bistriţa. Such work requires high-resolution photos and knot counts transferred to precise designs, and no fewer work hours as the originals. A red field-column carpet has already been donated to celebrate the church’s 500th anniversary.

Bruno Fröhlich is the senior pastor of the main German parish in Sighişoara, first recorded in 1298 as a Dominican church that later converted to Lutheranism. Among its 40 carpets is one with a donation inscription dated 1646. Pastor Fröhlich notes how in the 19th century the church took over from the guilds as the custodians of German patrimony, as industrialization displaced the highly skilled craft workers. As the laymen lost status, churchmen became the community’s symbolic representatives.

He muses about the carpets engaging in a kind of unspoken interfaith dialogue for the 21st century. “Romania is a meeting place of many faiths and ethnicities,” he says. “Go to Dobrogea [the Black Sea region], where prayer is called daily from minarets in Babadag, Constanţa, and Mangalia. And they are not just ethnic Turks and Tatars in mosques there. Many Arab students came to Romania during the Soviet period, and married and stayed on. Just as Braşov merchants controlled the Eastern trade routes, the physical distance—or should I say proximity?—has not changed in today’s times.”

Other pieces in the Brukenthal collection help close this story’s circle. A painting of St. Jerome by Lorenzo Lotto, whose painting of another saint, “The Alms of St. Anthony,” in Venice, gave his name to the most recognized design motif in all Anatolian carpets, hangs not far from a Lotto carpet originally from a nearby church. Just across the floor from this is a painting by the Romanian Theodore Aman, also born nearby, of an Orientalist room strewn with Ottoman rugs. Might his models have been some of the carpets now in the museum, once displayed in churches, one of them, perhaps, that very same Lotto?

About the Author

Louis Werner

Louis Werner is a writer and filmmaker living in New York City.

Matthieu Paley

Photojournalist Matthieu Paley specializes in documenting people and regions that are often misrepresented and is committed to issues relating to diminishing cultures and the environment. He is a regular contributor for National Geographic.

You may also be interested in...

A Fasting Journey Through Ramadan

Arts

What’s it like as a non-Muslim to fast during Ramadan? Writer Scott Baldauf shares his journey through the holy month where he uncovers resilience, empathy and the powerful unity found in shared traditions.

The Heart-Moving Sound of Zanzibar

Arts

Like Zanzibar itself, the ensemble style of music known as taarab brings together a blend of African, Arabic, Indian and European elements. Yet it stands on its own as a distinctive art form—for over a century, it has served as the island’s signature sound.

Sea Beans With Fava Beans and Dill

Food

This recipe serves up one of London-based food writer Sally Butcher's favorite lunches—a perfect mezze dish of beans.