A League of Their Own

- History

- Sport

- Migrations

Written by Dianna Wray

Photographed by Lisa Krantz

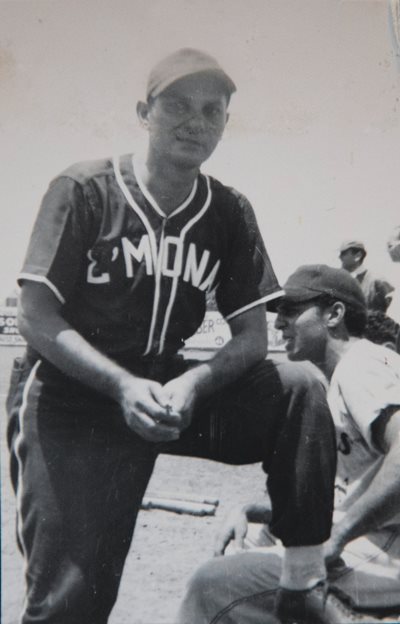

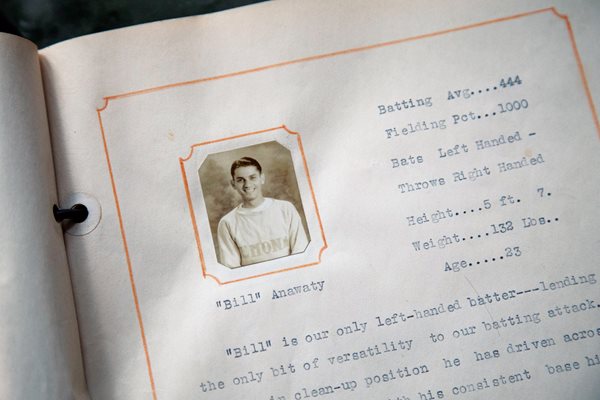

As he stepped up to the plate and turned to face the pitcher, everything else—the noise of the crowd, his work back at the newspaper, the parents and sisters he was supporting—dropped away that July day in 1931. On most days William “Bill” Anawaty was preoccupied with the business of life as a first-generation Syrian Lebanese American in the small oil town of Port Arthur, Texas. But as the slim 21-year-old waited for the ball to zip out of the pitcher’s hand, he was only a baseball player, the star of the Young Men’s Amusement Club Port Arthur, one of dozens of Syrian Lebanese baseball teams that had sprung up across the country in the 1910s and 1920s.

Maybe the pitcher from the Young Men’s Syrian Association team of Houston thought that he might strike out Port Arthur’s only left-handed batter, but Anawaty’s eyes were sharp as the ball sailed toward him. A satisfying pop as wood and leather-bound rubber connected, and Anawaty was off, legs pumping toward the bases whether he’d knocked the ball out of the park or not. The crowd, all from Syrian Lebanese communities across Texas, roared its approval. Many in the stands that day may not have grown up with the game, but they knew a great player when they saw one.

“It was the children of the first-generation immigrants who really played baseball,” says George Murr, a Houston lawyer and current president of the Southern Federation of Syrian Lebanese American Clubs whose dad played for the ymac team in Houston. “Their parents had all come over here, an abrupt baptism by fire of immigration, but the children, like my dad, were born here, and they had a true passion for the game.”

No one is entirely clear how the first teams came together, although each probably started in a similar way: as a casual game to spend an afternoon. Baseball was the national pastime, and players like Babe Ruth in the 1920s and ‘30s and Joe DiMaggio in the ‘40s and ‘50s dominated the sport—and captured the imagination of Anawaty and thousands of other Syrian Lebanese boys along with the rest of the country.

Anawaty’s parents had come in the 1890s, part of a wave of migration that saw the departure of nearly half the population of the Mount Lebanon region in what was then part of the Ottoman Empire. (The modern countries of Syria and Lebanon were established in 1920 and 1943, respectively.)

An estimated 60,000 Syrian Lebanese immigrants, most of them Christians, settled across the us from the 1880s to the 1930s. As the first generation of Syrian Lebanese Americans was born over the following years, the community would more than double in size.

The motives for immigration, says Akram Khater, a professor of history who specializes in diaspora studies at North Carolina State University, came mainly from the deteriorating Ottoman economy, which started a long downturn after the Suez Canal opened up in 1869. “This flooded markets with Japanese-made silk, and while there might have been other factors, like religion, the main reason people left was to go make some money. You could do that in America, so they came here, worked as peddlers or in factories. Then if they were successful—and a lot of them weren’t—they brought more family over.”

The first Syrian Lebanese immigrants to arrive in Texas stepped ashore in the 1880s, just a decade or so after baseball itself had showed up in the Lone Star State. (The first game in the state was reportedly played in Houston in 1867.) By the turn of the century, today’s National League and American League had been established, and the professional teams were making stars of gifted players like Ty Cobb, nicknamed “the Georgia Peach”; Walter “The Big Train” Johnson; Christy Mathewson, known as “Big Six” after a fire engine of the time; and baseball’s first true superstar, “the Sultan of Swat,” Babe Ruth. Anawaty and the rest of the boys, who were learning how to handle dual identities idolized the stars just like all the other kids, regardless of backgrounds.

But life in the us was far from simple. Much of the country, still segregated by race, often didn't know how to classify the Syrian Lebanese newcomers, who spoke Arabic, prepared their foods from home, often worked as peddlers and tended to settle together in cheaper areas of town.

“Wherever our people lived back then, they’d set up their own communities,” Peggy Karam, Anawaty’s daughter, recalls. “My dad’s family lived across the tracks in Port Arthur, with other Lebanese families.” They were, she adds, “so poor, and people treated them like dogs outside of their circles, so they kept to themselves. But the kids who were first born here, like my dad, they were American kids, and American kids played baseball.”

The Port Arthur team was formally created as part of the ymac, the organization established by Anawaty and his fellow teammates in 1925. “Assimilation happens both ways,” says Khater. Baseball itself “is arguably an assimilated form of cricket,” which came from England, he explains. “In games, in architecture, in so many different ways, this process isn’t so much a melting pot as it is a weaving together of disparate influences. So, of course the children of immigrants pick up baseball and make it their own.”

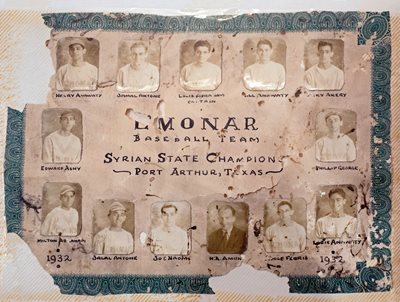

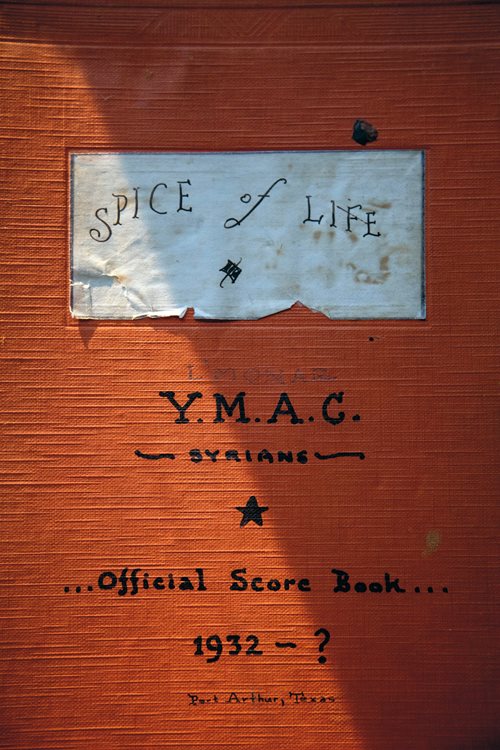

Soon the ymac began competing against teams from other Syrian Lebanese American organizations across Texas, and gradually those events became an excuse to hold tournaments that would bring teams from cities all over the South together to compete—and then dance, eat and socialize. “The competition was fierce, but the whole system was very casual at first,” says Peggy Karam’s husband Richard, whose father was also an avid player—for the team in San Antonio. “Just some games and then a picnic. But over time the picnics became parties and then banquets, a way for people to get together.” The Port Arthur team, which adopted the name L’Monar, meaning “guiding light,” in 1932, “was always the best team though. They dominated.”

A big reason for this was Anawaty himself. In addition to having a way with a bat, he also had no less of a way with words. Desperate for work during the Great Depression, he’d shown up on the doorstep of the editor of the Port Arthur Daily News after reading they were seeking to hire a copy boy. Thinking of his parents and six sisters at home, he’d refused to leave until the editor hired him.

On the field Anawaty was a gifted athlete, the team’s star. He was soon using his position at the paper to further celebrate his team’s exploits, making sure the stats for their games were recorded, from their few losses to, especially, their many victories.

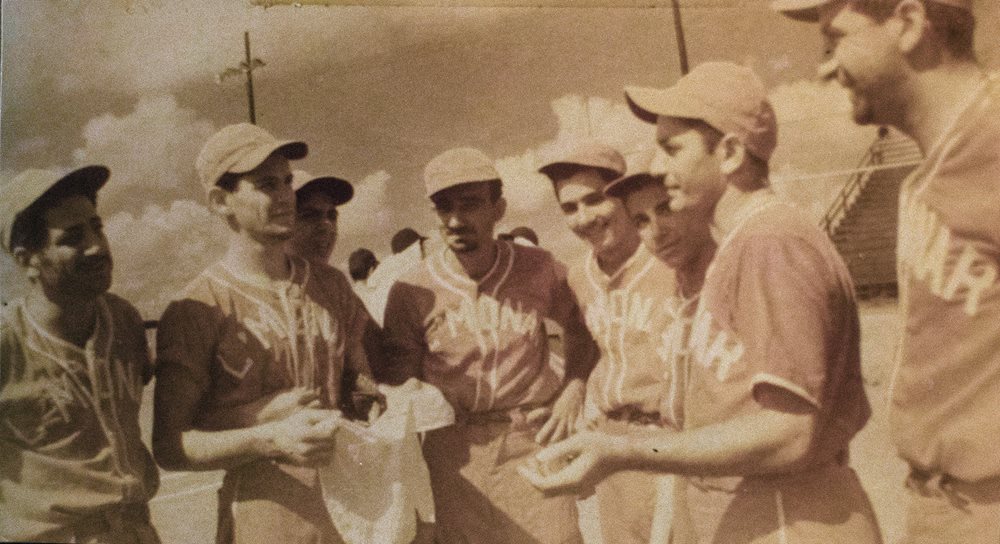

“I think it was because they were so poor,” Peggy Karam says. “But they could get together, and they could play on a team, and they could win. It was something they could achieve. They lived on the wrong side of the tracks in these towns, but on the field they were superheroes. They were strong. They might still speak Arabic and be newcomers to the American experience, but on the field they were as American as anyone else.”

That feeling of camaraderie also led Anawaty to ride his team’s popularity—they were nearly unbeatable, and who doesn’t love to cheer for a winning team?—to more formally connect the clubs that, by the early 1930s, were playing each other in regular tournaments across the South. There’d been talk of starting a federation to unite these clubs for years by then, but it had never taken off. Anawaty and his teammates hit upon a plan to draw enough potential members together in one place so they could hammer out the details. They mailed out invitations across Texas, Louisiana and the rest of the Gulf Coast inviting young Syrian Lebanese men and women to a Fourth of July celebration in Port Arthur. There’d be dancing and entertainment, of course—that was a given at any Syrian Lebanese gathering.

But the real draw? A game between Houston’s Young Men’s Syrian Association team, clad in mustard-yellow outfits that made them look like enormous bees, and Port Arthur, attired in simple white uniforms with the red caps of L’Monar, the team that compensated for a lack of funds with the prowess that had seen them lose only one game so far that season.

L’Monar dominated the game, and the dancing lasted until the early morning hours. By the end of festivities, the various groups had agreed in principle on a federation. It still took another year—and an evening of all the participants being locked in a ballroom at the Driskill Hotel in Austin, Texas, to settle the details. So began what is today the Southern Federation of Syrian Lebanese American Clubs, which today has chapters in more than 20 states.

“The kids who were first born here, like my dad, they were American kids, and American kids played baseball.”

—Peggy Karam

Over the following years, Anawaty married and had three children, but he stayed devoted to the team, saving records and stats and putting each of the annual team photos carefully in scrapbooks. He eventually wrote a book, The Spice of Life, that partly recalled L’Monar’s many triumphs. He even wrote poetry about those days, musing that it was fate that had provided them with talent for this game, a gift that “showered us with victory to increase our faith.” Their prowess on the baseball diamond, Peggy Karam says, helped them face the day-to-day challenges of belonging to a community often viewed with suspicion among publics whose politics often leaned isolationist. (The flood of Syrian Lebanese immigrants had abruptly slowed to a trickle after 1924 Immigration Act imposed strict quotas.)

“Some of my earliest memories are of watching Pop play baseball,” Peggy Karam says. She would go on to meet her husband of 44 years at one of the conventions of the Southern Federation. For a time the baseball games remained the group’s focus, with the honors of winning the tournaments fiercely prized. When Anawaty stopped taking the field himself, he became L’Monar’s manager. By the 1970s the teams were no longer the vital core of the expanding federations. “I think that maybe the need for them had passed after a while,” Murr says. “I knew my dad and my uncle played, but by the time I came along, the teams weren’t as important to the clubs as they’d once been.”

Still, in the 1980s there was an attempt to revive some teams, Peggy Karam recalls. “It was a nice try, with cousins and descendants of the original players out on the field, but everybody was a lot older by then,” she says, laughing a little. “Let’s just say the injuries were numerous, and after that, we tried bowling instead.”

The teams had served their purpose by then. “People don’t just abandon who they are even as they adopt being American. They transform as much as they are transformed by it. Baseball was another way for them all to come together, a way for them to connect and to reconnect with each other,” Khater says. “Outside of these games, they were different. They had to always be on their guard. But these baseball games were a way for them to just be, where there was nothing wrong with them just being themselves.”

About the Author

Dianna Wray

Dianna Wray is a nationally award-winning journalist and editor from Houston, Texas, and the current editor-in-chief of Houstonia magazine.

Lisa Krantz

Lisa Krantz is a staff photographer at the San Antonio Express-News and an adjunct professor at Texas A&M-San Antonio. She recently completed a year-long fellowship with the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University.

You may also be interested in...

Palermo's Palimpsest Roads

History

As the Mediterranean Sea's largest and most central island, Sicily has lured invaders, traders and travelers since antiquity, and each one has left its layers of legacy. From the ninth to the 12th century, Arabs and Normans dominated the island. Along its western coast, in its capital Palermo, the Arab-Norman royal court of King Roger I rose to become one of the most influential seats of power of its time. Since 2015 the UN has recognized a set of nine buildings whose syntheses of Byzantine, Arab and Norman designs epitomize the best of a time whose multiculturalism remains a foundation for Palermo today.

Muslim Perspectives on European Connections: A Conversation With Historian Ian Coller

History

It wasn’t until he found himself thousands of kilometers from his native Australia in September 2001 that Coller, a UCLA-Irvine professor of history, began to realize that his seemingly disparate early interests in French culture, Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, his longing to understand the Middle East and his determination to speak Arabic were all parts of his innate fascination with people.

The Staying Power of 4stay

History

As an 18-year-old from Tajikistan new to Washington, DC, Akobir Azamovich Akhmedov could barely afford the city’s high rents. A dozen years later, he is cofounder and CEO of 4stay, where his plug-and-play approach to long-term accommodations is reshaping the market.