Artists Answer COVID-19

- Arts

- Painting

- Photography

- Textiles

Written and curated by Beliz Tecirli

Inspiration, comfort, challenge, reflection, discussion—at no time do creative arts offer us more than during crisis. Faced with the closing of so many doors through travel bans, museum and gallery closures, lockdowns, quarantines and social distancing, artists of all kinds are responding with new ways to make new connections on new platforms to articulate this moment in history.

For visual artists and their artistic practices, the challenges of covid-19 have inspired everything from revisiting previous works while in lockdown to creating something entirely new in direct response to the crisis. Here, we look at a selection of artworks, all undertaken since February by artists of Middle Eastern heritage or residence, that pertain loosely to themes of isolation, lifestyle, access, environment and healing. The artists are only a few of the many who, amid coping with their own personal obstacles, continue to create, collaborate and encourage art that, as the works here show, proves both culturally particular and universal.

Coming to Terms with Isolation

While quarantines and social distancing may be our best defenses against the virus, even surveys conducted earlier this year by the medical journal The Lancet Psychiatry and the uk Academy of Medical Science forecast “profound” and “pervasive” impacts on mental health that research since has borne out. With the global economy forecast to contract as much as 1.75 percent in 2020, it is increasingly clear that the effects of the pandemic will be with us for some time.

Artistic responses arose almost instantaneously, such as the quick, iconically virus-themed napkin sketch, penned by Almigdad Aidikhaiiry, and a painting of a face-masked man by Salah El Mur (both coincidentally from Sudan).

The uncertain boundaries between fever dreams and reality, as well as cell biology became themes for the Dubai-based design studio Apical Reform, known for its kinetic works and founded by Amrish Patel. The several resulting pieces, which use a “digital canvas” to display gently moving, digital images, all showed the tendency of early covid-themed art to address the general fear of an unknown and novel coronavirus.

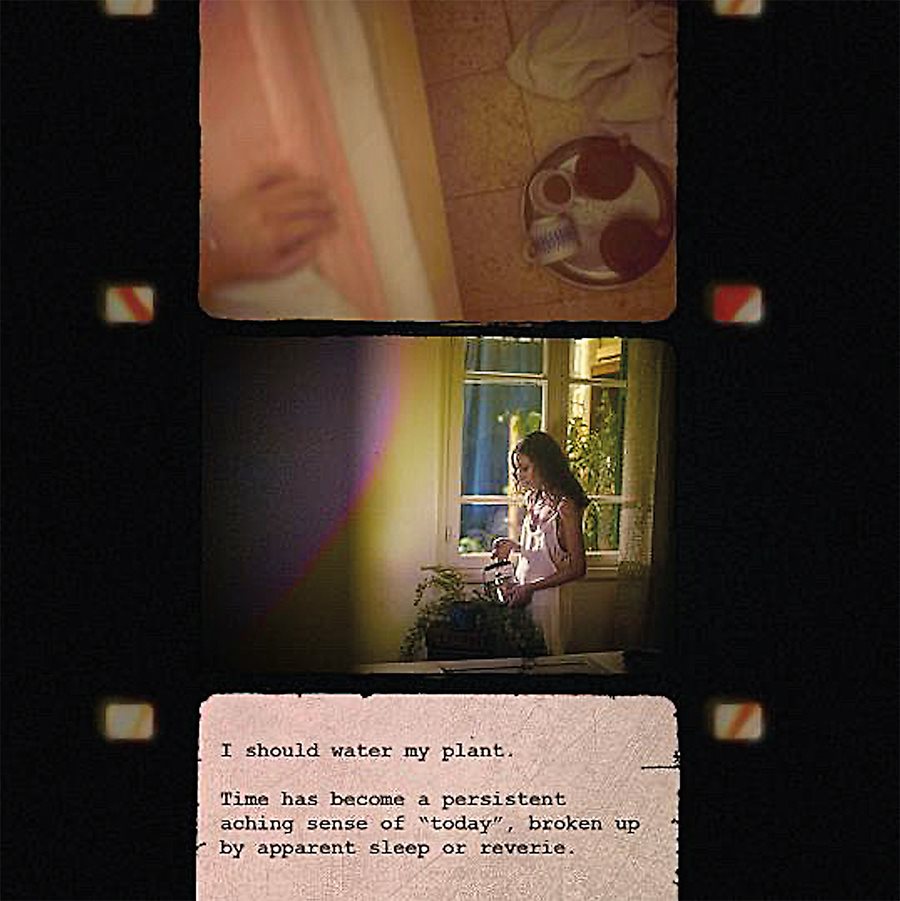

For some, however, isolation played to existing specialities. Lebanese photographer and filmmaker Omar Sfeir looks often at intimacy and human relationships. His most recent work, carried out in collaboration with poet Nadia Hassan, hones in on the psychological pressures of isolation. Hassan’s poetry feels raw and unedited, inspiring in Sfeir a complementary, seemingly spontaneous photographic esthetic, producing together effects greater than either could alone.

For Saudi acrylic artist Jassim Al Dhamin, “Art was the only way to escape,” he says, from both isolation and worry. Tapping his emotions, Al Dhamin’s covid-fueled work focuses on the ambiguously similar physical sensations of flying and falling, employing his signature palette and expressive linage to evoke instability.

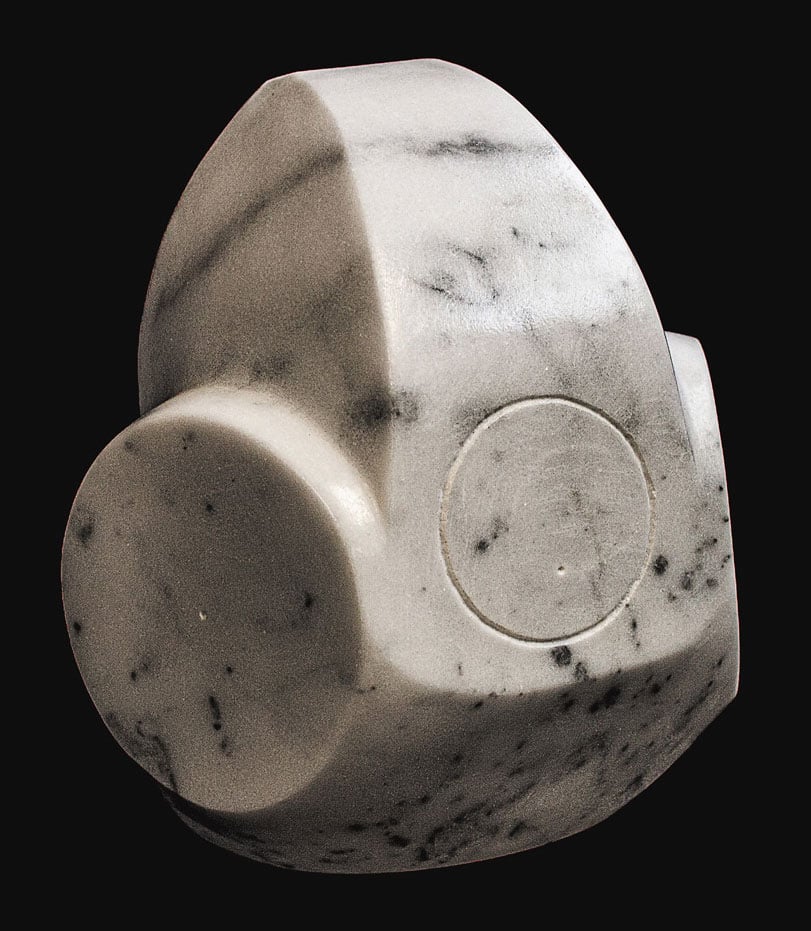

For others, isolation led to outreach. Renowned sculptor Athar Jaber, born to Iraqi parents and currently living in Antwerp, Belgium, says he asked himself, “How can art and artists directly contribute to society?” This motivated him to mobilize his stone-working skills to carve from marble 10 different interpretations of face masks, sell them and donate the proceeds to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. He dedicated the project, which he titled A Mask for Life, to the people who often have little or no physical space for the social distancing covid-19 demands, “making them among the most vulnerable people” around the world, he says.

Shifting Lifestyles

As contemporary artworks are being conceived and brought into existence in relative isolation, covid-19 is providing a moment to reflect upon artistic practice and lifestyles as a whole.

Syrian-born artist Osama Esid, who now resides in Minnesota, has used the slower pace of pandemic life to re-edit and compile old works in his usual medium of painted photographs in colored oils while developing new techniques. These include the use of a filament pen to draw directly on celluloid and then printing the images using either silver gelatin photographic paper or a printing press.

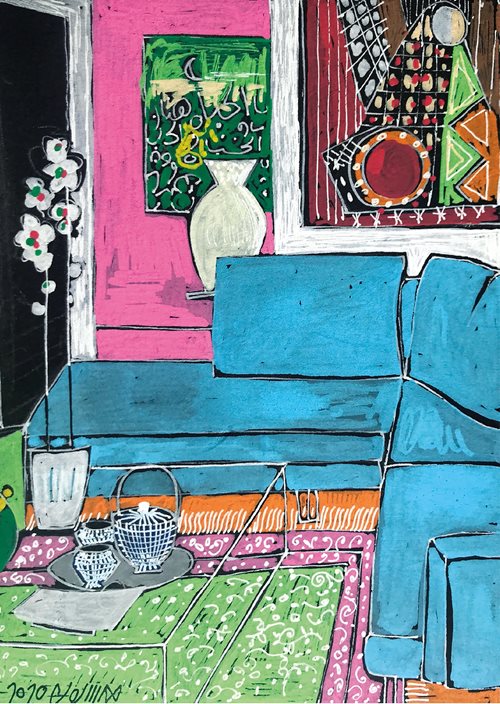

Similarly, Beirut-based painter Tagreed Darghouth says the quietude of social distancing offered “an opportunity to focus” while retaining her usual routines of long days in her studio.

Also working in Lebanon from a home and studio he calls his “little island” amid the mountains above Beirut, Nadim Karam says he has welcomed the opportunity quarantine has given him to invite members of his family into his practice through direct participation in creating some of his large-scale works.

On August 4, for Darghouth, Karam and thousands of others in Beirut, the explosion in the city’s port shattered far more than just the windows and glass doors of studios and homes. “Hundreds and thousands, friends and acquaintances, dead, injured and displaced. This disaster has changed our lives forever,” Karam laments before shifting to resolution. “Although coronavirus created a definite change, this disaster brings forward a wind of fresh energy”—energy he says should be mobilized as “creative power” to push for political and social change.

Shifting Accessibility

With museums, galleries, theaters and other arts venues largely shut down, the ways artists interact with audiences has shifted, too. Many artists have taken this as an opportunity to utilize the Internet more than ever to invent new collaborations and reach new audiences.

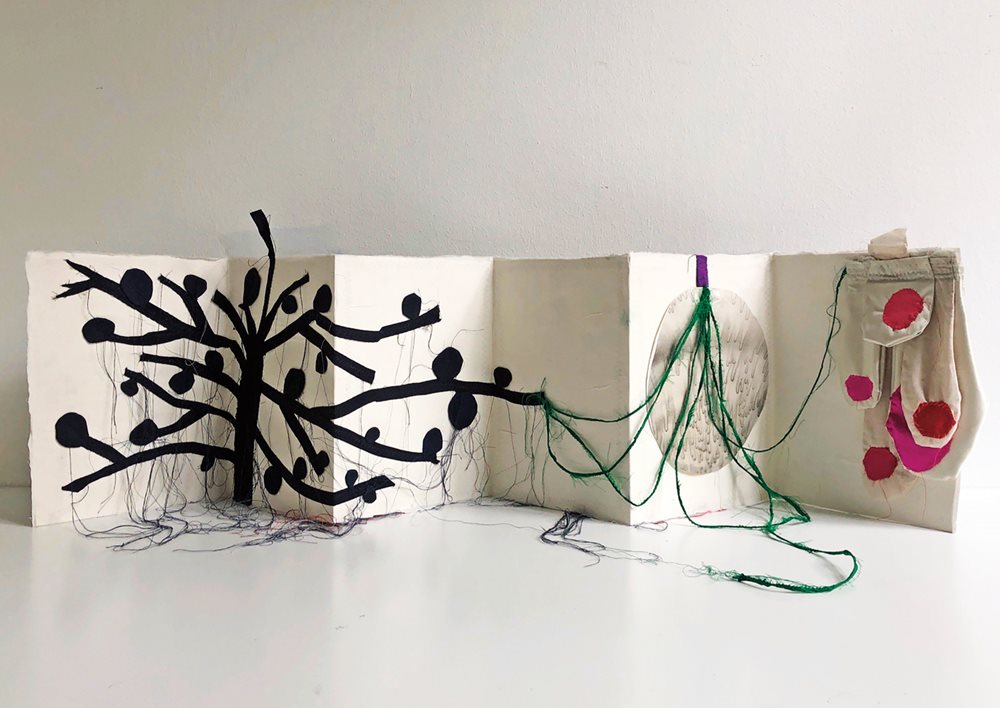

From April to July, The Mosaic Rooms, a nonprofit art gallery and bookshop dedicated to contemporary culture from the Arab world and beyond in London, worked remotely with local secondary schools on a four-week art project titled Together Apart: Lockdown Diaries. Artists Aya Haidar, Marwan Kaabour and Rosie Thwaites invited 60 students from The Cardinal Vaughan Memorial School and Kensington Aldridge Academy to respond to weekly briefs on social distancing, daily exercise, pandemic hygiene and remote relationships. The teachers expressed excitement at exploring “relevant new ground” using digital learning, and students enjoyed expressing freely and personally about their own relationship to the lockdown.

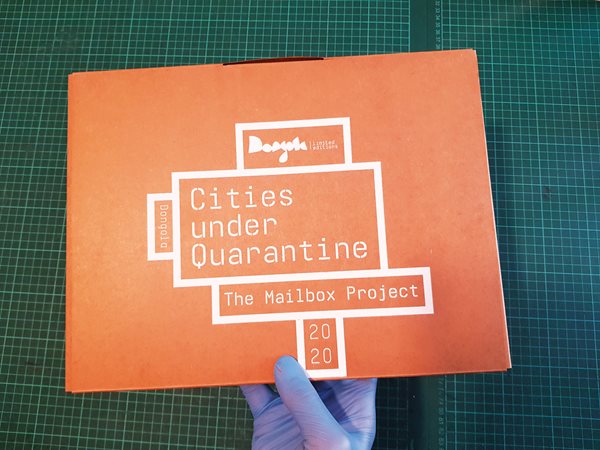

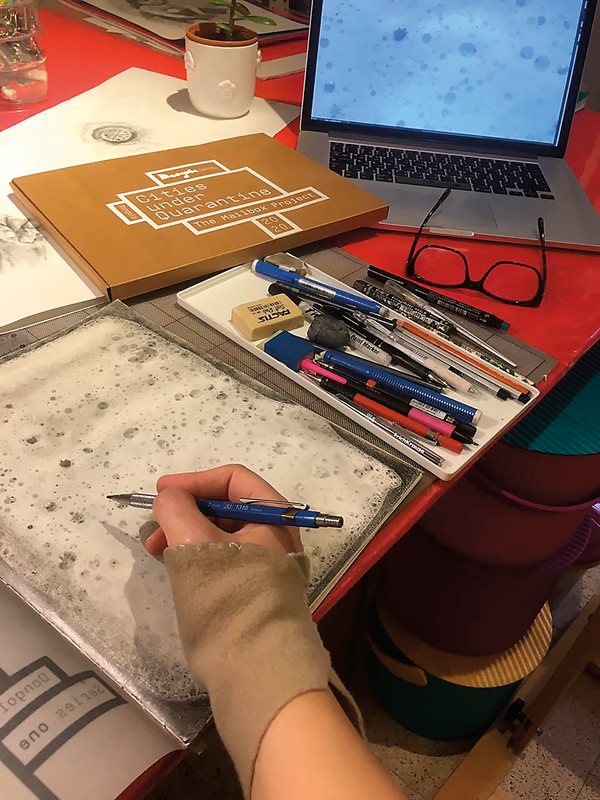

Similarly, Abed Al Kadiri—another Beirut-based artist who also lost work in the August 4 explosion—has promoted artist-to-artist collaboration through Cities Under Quarantine: The Mailbox Project. Responding to the closure of public places, he created and shipped identical, handmade art books, all pages blank, to 57 artists across the Middle East, North Africa, Europe and Asia. He invited each artist to fill the pages, which Kadiri plans to publish alongside essays in what he hopes will be “a common space for artists to express and explore this moment in history.” An exhibition, he says, may follow when galleries can reopen.

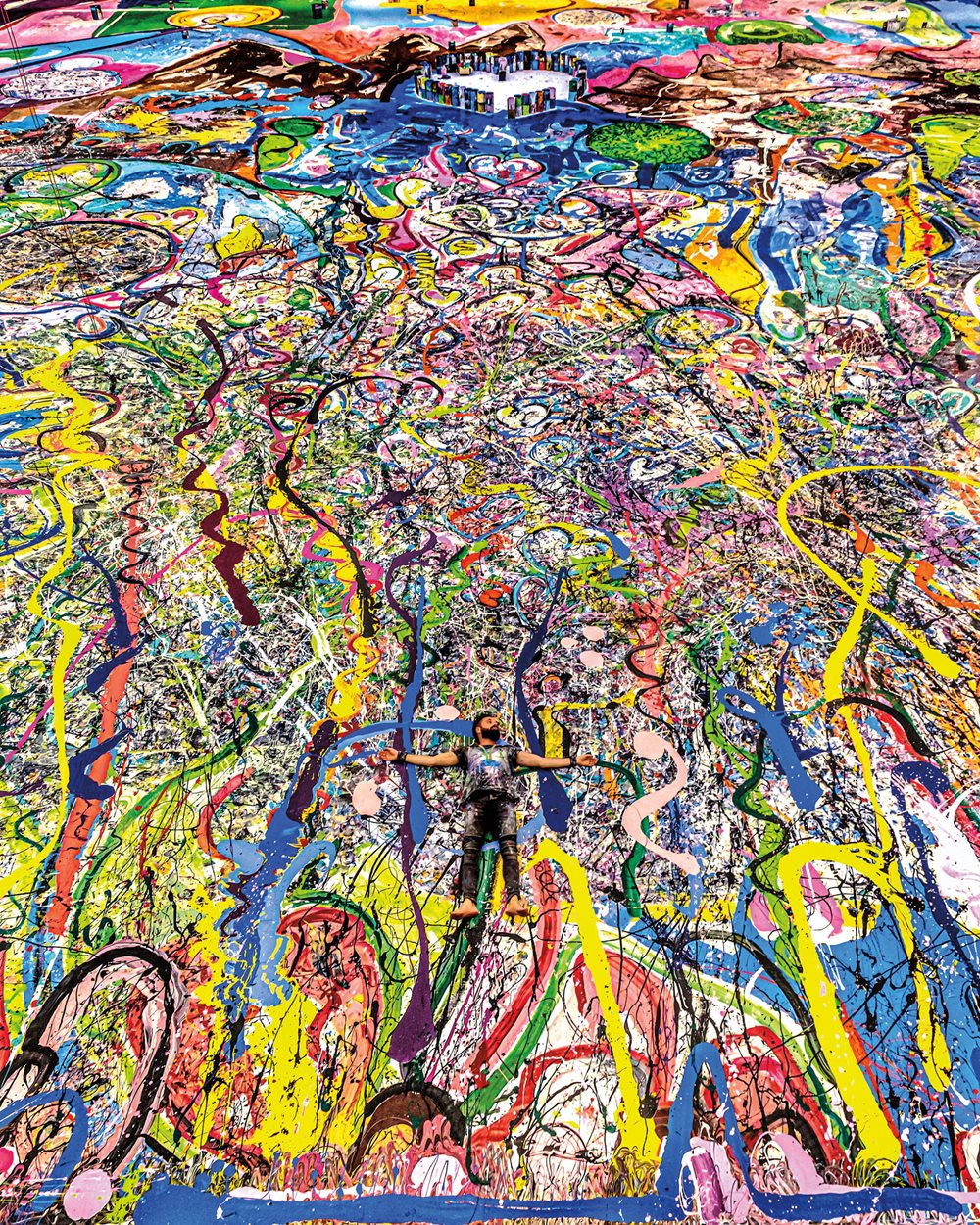

On a vastly larger scale, inside a great ballroom of Dubai’s iconic Atlantis hotel, painter Sacha Jafri has embarked on a record breaker: He is attempting to create the largest painting ever to cover a single canvas. Spreading over some 2,000 square meters, the work he has titled “The Journey of Humanity” is also both collaborative and charitable. While Jafri will complete much himself, through his website and social media he has invited children from across the globe to share their own artworks on the themes of “connection and isolation.” He will collage the children’s works within large circular “portals” set amid Jafri’s own expressionistic puddles, splashes and strokes of electric color. Upon completion, Jafri plans to auction the work as 60 individually framed pieces and donate what he hopes will be as much as $30 million to charities serving children in extreme poverty worldwide.

Other projects address our diminished relationships to public spaces, such as “Project 003278079060” by the artist called Neither and Marc Buchy. This turned a voicemail system into a space to host sound-based art, in turn establishing a virtual, interactive audio exhibition space without the Internet. Because the recordings eventually expired, the work created an ephemeral discourse between the recordings themselves and the memories of them.

Empty public spaces themselves have become creative material for Palestinian artist Jack Persekian, who has continued his series Gates of Jerusalem, in which he composites and superimposes historic and contemporary photos of the old city’s gates, towers and other well-known landmarks. Similarly, Madinah-based artist-photographer Moath Alofi is treating his city of birth as his studio and museum, exploring and documenting both its barren and urbanized spaces.

Shifting Environmental Concerns

While public spaces remain problematic, artists like Saudi photographer Dhafer Al Shehri remind us that even our forms of virus protection are having impacts in the public environment. With images that allude to the hazards of material pollution from predominantly plastic, nonrecyclable and nonbiodegradable personal protective equipment (ppe), he helps us consider whether such environmental pollution is a temporary nuisance we must accept when fighting a global virus, part of a long-term environmental disaster or both. With such waste already damaging the world’s oceans and the essential production of ppe continually increasing, such artworks are fundamental in transmitting an urgent message about our methods of disposal.

Others including Los Angeles-based Sudanese American artist Almigdad Aidikhaiiry approach covid-19 as an opportunity and indeed an alarm for “change in the direction of humanity.” Aidikhaiiry’s visual works often use playful colors and seemingly whimsical forms that captivate the beauty of the natural world to serve up compelling truths about climate change, deforestation and other threats to ecosystems alongside strategies for change—all of which he makes memorably clear in the title and motifs of his painting “Clarion Call.”

Art as Therapy, Healing and Material Memory

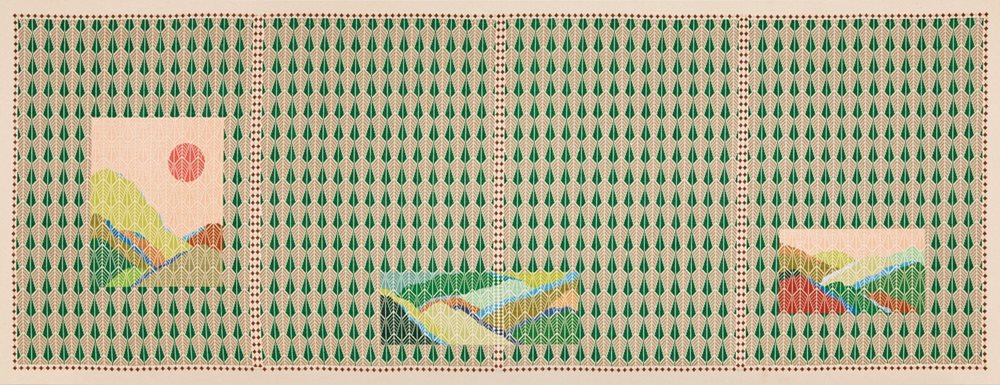

Let’s Tatreez!, another project spearheaded by The Mosaic Rooms, saw textile artist Jordan Nassar design cross-stitch patterns inspired by the rich history of Palestinian embroidery. He then provided the patterns for free download, alongside how-to tips so that audiences online could take on the traditional, meditative craft at home. The project encourages participants to improvise and embellish designs with personal flair, and then to post images of them on Instagram under #letstatreez. Seemingly simple, such work signifies so much in a time like ours, drawing to mind the long-running tradition of community-based handicrafts, which both replicate and innovate passed-down patterns but this time carried out by long-distance collaboration.

To a similar end of healing through meditative practice and textile art, Abu Dhabi resident Banu Çolak has drawn nature into her home by painting textiles and creating prints using natural paints handcrafted from herbs, spices and plant oils. As a result, these works feature repetitive patterns in earthy tones. They bring a breath of the natural world into the enclosed environments that we each inhabit in this crisis.

Beyond coping with new circumstances and seeking in creative practice relief from the stresses of the pandemic, art in the time of covid-19 is also the formation of collective memory. The concerns expressed, be they personal, social, spatial or environmental, together they are painting the greater picture of our time.

As many of these artworks have been exhibited only online due to a lack of alternatives, they have also thus proven to be part of one of the most sweepingly immediate and far-reaching artistic responses to global crisis in history. In this way, they are emotional touchstones for today and contributions to a shared global heritage for tomorrow.

Thank you to all the artists who shared work and experiences for this article. Thank you also to Omar al-Qattan, chairman of the board for the A.M. Qattan Foundation; Mahmoud Abu Hashhash, director of the foundation's Culture and Arts Programme; Flora Bain, manager of communications and outreach for The Mosaic Rooms; Stephen Stapleton, founder of CULTURUNNERS; journalist Rebecca Anne Proctor; and artist Ajax W. Axe. –Beliz Tecirli

You may also be interested in...

FirstLook: Ramadan Picnic

Arts

On a warm June evening, people gathered at a park in Bethesda, Maryland, for a community potluck dinner welcoming the start of Ramadan.

FirstLook: Ramadan’s Lanterns

Arts

In the March/April 1992 issue, writer and photographer John Feeney took AramcoWorld readers on a walk through the streets of Cairo during Ramadan.

Spider Silk Weaves Web of Intrigue in Middle East Debut

Arts

Creators Simon Peers and Nicholas Godley present three exquisite textiles and a cape made from the silk of golden orb-weavers found in Madagascar.