There are those who say that Lawrence has received altogether too much “publicity” through me…. There may be something in this, though I doubt it. But, if there is, the blame should all be mine.

—Lowell Thomas, With Lawrence in Arabia, 1924

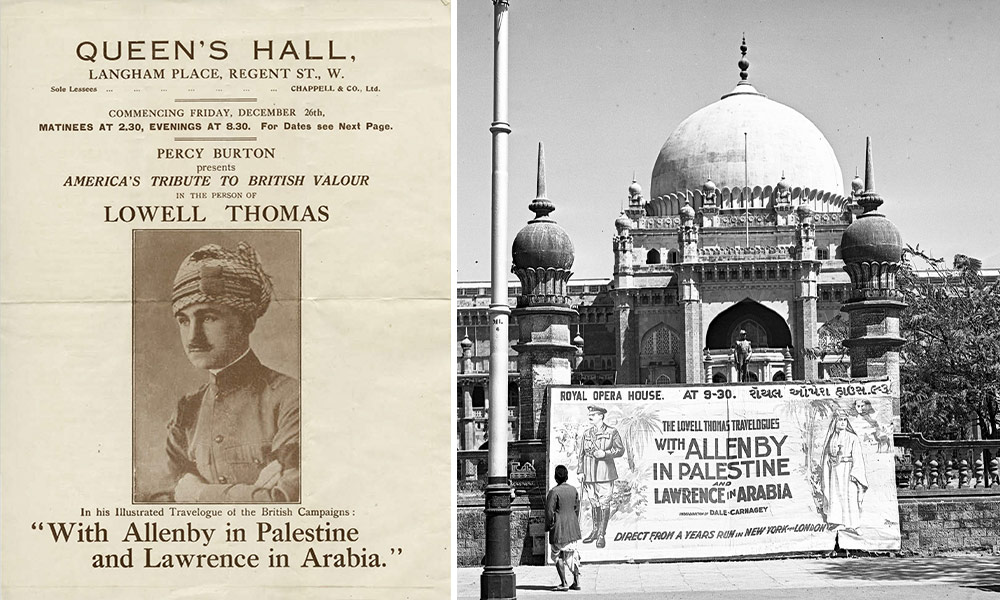

On the evening of August 14, 1919, a full house gathered at London’s Royal Opera House for a show about which they had heard extraordinary reports from New York society. So novel and so elaborate was the entertainment, now regarded as the world’s first multimedia event, that its producer, Lowell Thomas, had been invited to attend by King George v.

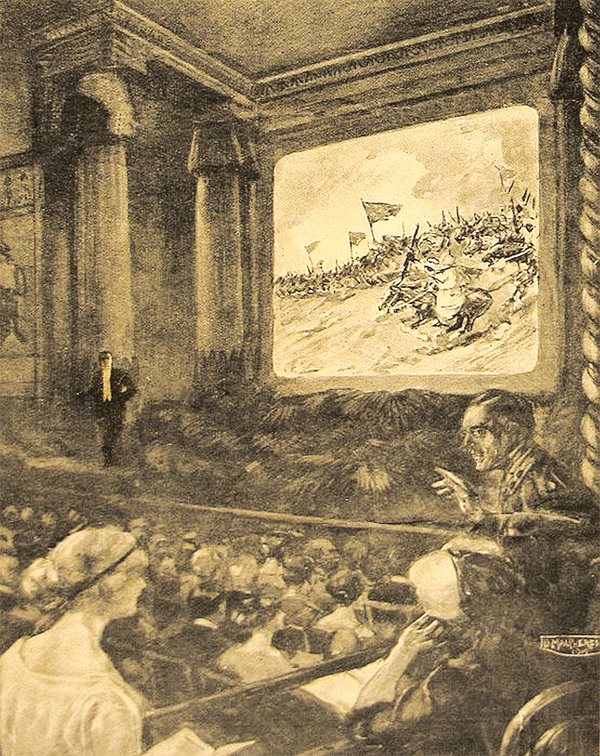

Those present were not disappointed. As the curtain rose, it revealed a scene that transported the audience to a place whose stereotypes loomed large in the popular mind—“the mysterious Orient.” Braziers of incense wafted musk across the stalls. A dancer swayed before backlit images of the Pyramids. Palm trees filled the orchestra pit, and the band of the Welsh Guards struck up a rousing musical accompaniment.

Expectations primed, the audience watched as the screen at center stage came to life. Black-and-white motion picture film opened a world of majestic desert and mountain landscapes filled with rifle-bearing Arab tribesmen, camels and horses mixed in with British-supplied armored cars, uniformed soldiers and tented encampments, all wrapped in an air of noble purpose. Thus it was that a century ago, the story of what was called the “Arab Revolt,” and its part in helping win a distant war, began to unfold. As it did, the character at the heart of the story was British Army officer and former archeologist Thomas Edward Lawrence, who began his journey into the public imagination, establishing his legend as “Lawrence of Arabia,” the most enduring icon of heroism to emerge from World War i.

The mastermind of the show was Lowell Thomas, a us journalist, publicist, filmmaker and adventurer who, that evening, took up the live narration from a lectern on stage. He calibrated his script to deliver a hero: “At this moment, somewhere in London, hiding from a host of feminine admirers, reporters, book publishers, autograph fiends and every species of hero-worshipper, is a young man whose name will go down in history beside those of Sir Francis Drake, Sir Walter Raleigh, Lord Clive, Charles Gordon, and all the other famous heroes of Great Britain’s glorious past.”

With the craft of a master storyteller, Thomas drew his audience into the scenes unfolding on the silent film. The production was made more thrilling and immersive by the novel use of three synchronized projectors that Thomas’s cameraman, Harry Chase, had configured to realize combinations of motion pictures and still images in full color alongside sound effects.

With Allenby in Palestine and Lawrence in Arabia proved as successful as it was ambitious. The Strand Magazine hyperbolically endorsed it as “the greatest romance of real life ever told.” The show, complete with its two-tonne projection booth and three carbon arc projectors soon relocated to play at the far larger Royal Albert Hall in London. More showings around the world followed and the film ultimately pulled in a total of four million people. Thomas and cameraman Chase earned $1.5 million, worth around $22 million today.

The show was spectacular enough for its era, but what made it so authoritative, riveting and convincing were Thomas’s direct experiences of the events he had filmed, which he went on to describe with oratorical brilliance. The combination created something altogether new and potent, a mix of news reportage, documentary record and propaganda tract with immediate significance in the ongoing political realignment of the post- World War i Middle East.

Supporting the us Entry into the War

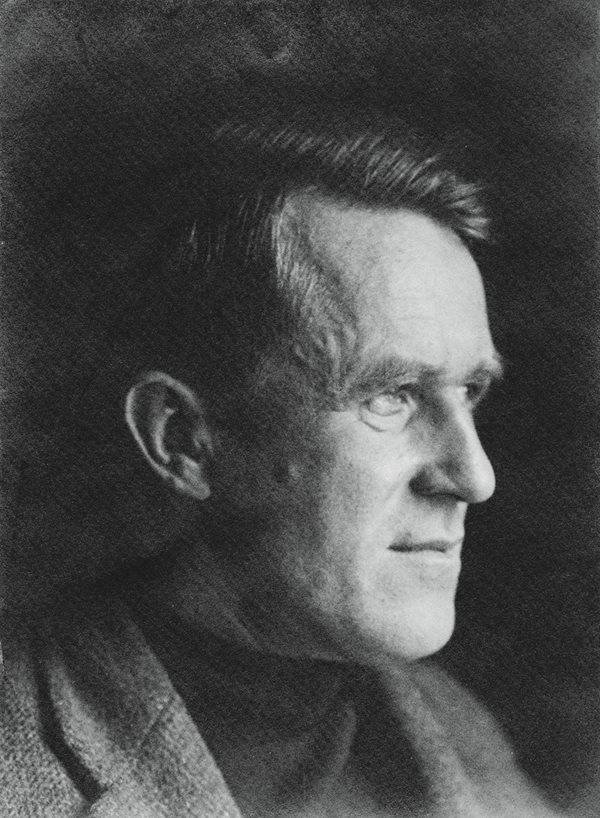

The us entered the war on April 6, 1917, but as its soldiers headed for the Western Front, us public opinion was not widely supportive. To help sell the case for joining the war, the us War Department approached Thomas with a request “to gather material and stories that would encourage the American people’s support” for the war.

The mobilization of Lawrence as a propaganda instrument, and the projection of his personality to frame a wider imperial ambition, proved groundbreaking.

Thomas was already a successful publicist and promoter. Born in Ohio to professional parents, he had moved with the family to Colorado and attended the University of Denver, followed by a stint on the Chicago Daily Journal. Thomas went on to earn a master’s degree and teach oratory classes at Princeton University. At 25, he persuaded railroad companies to let him travel free in return for editorial coverage; he had also completed an Alaska travelog for a campaign initiated by us Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane, titled “See America First”—a line that would appear for decades promoting domestic tourism.

For the war project, Thomas raised $75,000 from a group of Chicago businessmen. With Chase, he made his way to France, seeking in the trenches a suitably heroic narrative. However, the mud and carnage proved far more tragic than inspirational. Thomas diverted to Jerusalem in November 1917 as an accredited war correspondent, intending to film the entry of the victorious British forces of General Edmund Allenby into the captured city at the start of December. It was there that on February 28, 1918, Thomas met Lawrence, who promptly agreed to allow him and Chase to film Lawrence’s irregular Arab forces. Thomas and Chase subsequently spent two weeks with Lawrence and the Hashemite Prince Faisal, son of British ally Sharif Hussein of Makkah. Chase shot six reels of film.

From the moment he met Lawrence, Thomas recognized that he was in the presence of a potential public-relations powerhouse. Recalling their encounter in his book With Lawrence in Arabia, Thomas quoted British Governor of Jerusalem Sir Ronald Storrs’ introduction: “I want you to meet Colonel Lawrence, the uncrowned king of Arabia.”

The mobilization of Lawrence as a propaganda instrument, and the projection of his personality to frame a wider imperial ambition, proved groundbreaking. Thomas’s blend of military prowess, distant-land romance and enigmatic heroism—all of which Lawrence offered—wove a cloak of glamor and intrigue for the raw material of battlefield success. It sold a vision of the war’s nobility of purpose that had been largely lost in the trenches of the Western Front.

In realizing these possibilities, Thomas showed himself a genius of populist publicity who understood the potential power of the moving image in the new style increasingly in demand from the Allied war effort. His firsthand, eyewitness accounts furthered the documentary medium that had been pioneered in 1916 by Geoffrey Malins’s film of the Western Front, The Battle of the Somme. Later, the power of frontline documentary was to advance in World War ii, in particular through us directors such as Frank Capra, John Ford and John Huston.

The Alliance of Convenience

As much as Thomas was using Lawrence as a vehicle for his ambitions, the reverse was no less true. The star of the show was by disposition introverted, complex and slow to reveal his deeper thoughts and emotions, and these were precisely the qualities that contributed to his celebrity mystique. Lawrence and Thomas developed a mutual respect for one another during their brief time in the desert, and Lawrence engaged directly with Thomas’s project in London in early 1919 in order to disseminate the facts of the Arab Revolt—and his own role in it—more widely.

He viewed the publicity generated by Thomas’s films as potentially influential both in promoting his own work and in the larger British negotiations for the postwar settlement of the former Ottoman Middle East, which began at Versailles in January 1919 and lasted through the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920. Lawrence’s interest lay in persuading leaders to favor Arab self-determination, both with an independent Palestine and with the interests of the Hashemite dynasty that had supported the British in their efforts to oust the Turks from the Arabian Peninsula. Secretary of State for War and Air Winston Churchill recalled his first meeting with Lawrence in Paris: “It soon became evident that his cause was not going well in Paris. He accompanied Faisal everywhere as a friend and interpreter. He scorned his English connections and all questions of his own career compared to what he regarded as his duty to the Arabs.”

Lawrence saw Thomas’s show a number of times. He even posed in London in early 1919 for portraits in Arab dress by Chase in order to strengthen his personal story line. However, it was not long until his struggle with fame made him ambivalent toward Thomas’s project and his role in it. Thomas would famously articulate this growing contradiction in Lawrence’s nature with the remark that Lawrence “had a genius for backing into the limelight.”

Lawrence’s political vision for the region was eventually eclipsed by the British and French imperial agendas. So, too, was Thomas’s original purpose, as the war ended before his film could be deployed as an active tool in the battle for public opinion.

Today, Lawrence is seen largely through the no-less-seductive cinematic prism of the blockbuster epic Lawrence of Arabia, produced in 1962 and directed by David Lean, who cast Peter O’Toole as a tall, blond and blue-eyed version of Lawrence. The character of Thomas, and his role in lionizing Lawrence, figures into the second part of the film. (See box, above.)

The events that underpinned what became the legend of Lawrence of Arabia were extraordinary by any measure, but it was Thomas’s genius to use those events to tell a particular story, one that ultimately focused less on facts than on celebrating wider Western cultural values of individualism, courage, tenacity, loyalty and pursuit of grand purpose. Over time, however, this romantic characterization of Lawrence and his story has been understood alongside the contradictions of the vulnerable psyche. At its center, the ambitious yet self-doubting, reluctant yet vain leader is engaged in a struggle with his own nature that was as doomed as the political cause he advanced. This central fault line in Lawrence’s character led him to withdraw from public life in 1922, when he enlisted in the Royal Air Force under the assumed name of John Hume Ross.

Across the Atlantic, Thomas’s postwar story could not be more different. His ascent to fame and fortune seemed unstoppable. In the process of realizing With Allenby In Palestine and With Lawrence in Arabia, he had created a widely recognized masterpiece, an inspiring populist event and enduring cinematic milestone that drew the great, the good and the ordinary, including British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, Winston Churchill and even General Sir Edmund Allenby himself.

In his introduction to With Lawrence of Arabia, Thomas admits that he may have gone too far in praising Lawrence. Somewhat defensively, he wrote, “There are those who say that Lawrence has received altogether too much ‘publicity’ through me. They piously declare that this is not in accordance with military ethics. There may be something in this, though I doubt it. But, if there is, the blame should all be mine.”

Thomas went on to become America’s first iconic news anchorman, where at both cbs Radio and nbc his signature greeting, “Good evening, everybody,” was recognized across the country. On the way, he was to host radio shows, front travelogs and write numerous travel-and-adventure books. In 1939, he anchored the first us television news broadcast. He went into business in 1952 to develop the Cinerama surround-screen movie format—33 years after he had debuted the concept with the three-projector booth in Covent Garden. Thomas lived to 89 years old.

Lawrence passed the post-World War i years with increasing troubles. Living in self-imposed obscurity, in 1935 at age 46, he fatally crashed his motorcycle to avoid a local cyclist near his Dorset home in southwest England.

You may also be interested in...

Hijrah: A Journey That Changed the World

History

Arts

Avoiding main roads due to threats to his life, in 622 CE the Prophet Muhammad and his followers escaped north from Makkah to Madinah by riding through the rugged western Arabian Peninsula along path whose precise contours have been traced only recently. Known as the Hijrah, or migration, their eight-day journey became the beginning of the Islamic calendar, and this spring, the exhibition "Hijrah: In the Footsteps of the Prophet," at Ithra in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, explored the journey itself and its memories-as-story to expand understandings of what the Hijrah has meant both for Muslims and the rest of a the world. "This is a story that addresses universal human themes," says co-curator Idries Trevathan.

Animated Narratives for New Eyes

Arts

The Japanese style of animation known as anime is underpinned with narratives of community, loyalty and collective purpose. Its ubiquity feeds a growing appetite for the art form, becoming popular in the Middle East.

A Land and a Camera: The Legend of Sami Kafati

Arts

By tackling often overlooked societal issues, Palestinian-born Sami Kafati’s body of work has shaped Honduran cinema even years after his passing.