The Dialogues of Don Quixote

- Arts

- History

Written and photographed by Tom Verde

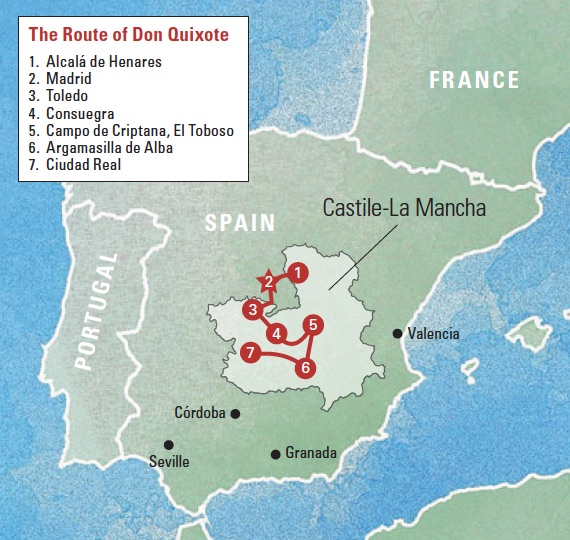

Several chapters into Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote, the fictional narrator takes a hard detour from the action, in which the hapless hero has been battling windmills and other imaginary foes on the rolling plains of La Mancha, and deposits the reader in the city of Toledo’s central marketplace, the Alcaná.

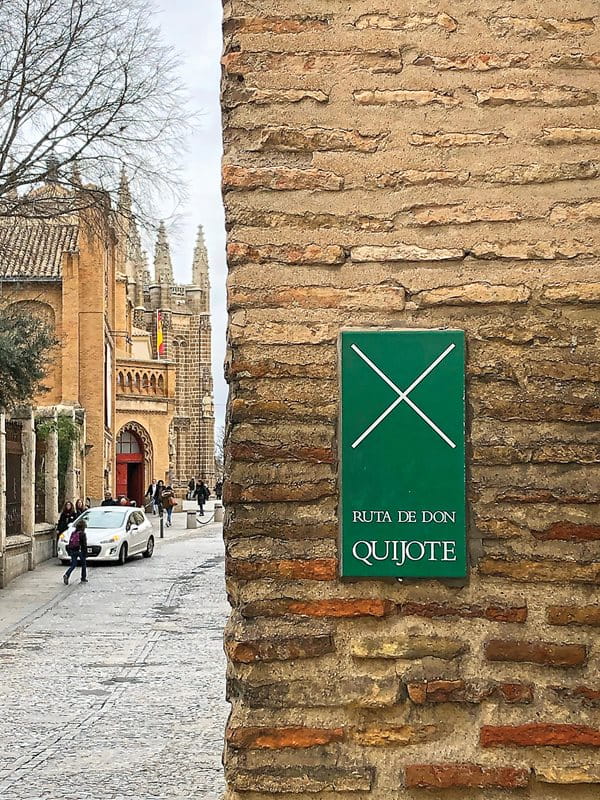

Four centuries later, I wandered the labyrinthine streets of Toledo’s old quarter and ended up, like most pedestrians, in the Alcaná, a name that comes from the Arabic al-janat, meaning “the (market) stands.” It is still a bustling center of commerce, and a plaque, inconspicuously tucked beneath a second story window, commemorates the spot’s connection to Don Quixote. Along my way, I passed historic city gates and buildings awash in horseshoe arches, decorative tiles and intricate plasterwork, all reflecting the medieval and early Renaissance Christian enthusiasm for designs that flourished in al-Andalus, or Muslim Spain. Overshadowing the lot loomed the massive profile of Toledo Cathedral, a glorious synthesis of Gothic and Islamic architectural styles. During the 12th and 13th centuries, Jewish, Muslim, and Christian scholars from various parts of Europe flocked here to translate philosophical and scientific works from classical Arabic into Latin, Hebrew, Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) and vernacular Castilian. Centered in and around the cathedral cloister, the collective effort gained fame as Toledo’s “School of Translators.”

Given this long multilingual and multinational history, it comes as no surprise that Cervantes chose Toledo for what happens next in the novel. Stumbling upon an intriguing Arabic manuscript being sold for scrap among the Alcaná’s warren of shops, the narrator seeks out a translator. Upon locating an obliging, Castilian-speaking Morisco—a descendent of Spanish Muslims forcibly converted to Christianity—he learns the author of the text is a fictional Arab historian named Cide Hamete Benengeli.

Here, as he does elsewhere, Cervantes signals links to Arab-Moorish identities. Cide is equivalent to Señor, derived from the Arabic sayyid, meaning “sir.” Hamete comes from Hamid, a popular Arab name. Benengeli, or berenjena in Spanish, means “eater of eggplant,” a vegetable associated with the diets of both Moriscos and Conversos, Spanish Jews who were likewise forced to convert. The narrator is further delighted to learn the manuscript is entitled History of Don Quixote of La Mancha, a purportedly historical account of the very book the narrator has been, thus far in the novel, describing to the reader.

Paying for the manuscript with a half-reale coin, the narrator then retires with the interpreter to the cathedral cloister and has him translate more. Ultimately, he hires the Morisco to spend the next month and a half under his roof, translating “the entire history, just as it is related here.”

So from this point on, the primary narrator of one of Western literature’s seminal masterpieces—a work the late literary critic Harold Bloom identified as the world’s “first modern novel”—is in fact an Arab chronicler. While a figment of Cervantes’ imagination, Cide Hamete Benengeli is equally the product of Spanish literary, political and cultural history. He is also not the only character with Muslim roots to appear in the novel. Throughout Don Quixote, Cervantes makes frequent references to Islamic culture, the Arabic language, and the longstanding relations that existed among Spain’s various ethno-religious groups.

“The point Cervantes is making with the Morisco interpreter is that there are still people running around Toledo who know Arabic or Hebrew, and so he is pushing back against the idea that Spain has somehow become a purely Catholic country that doesn’t bear traces of its long history of the presence of Jews and Muslims on the peninsula,” Barbara Fuchs, professor of Spanish and English at UCLA, told me before I left for Spain. Controversially, Cervantes also took issue with the fate of the Moriscos, whose exile from the Iberian Peninsula in the early 17th century ended 900 years of convivencia, or coexistence. Yes, Don Quixote is a famously funny novel, Fuchs acknowledged. But it is also, in her opinion, “a very subversive book.”

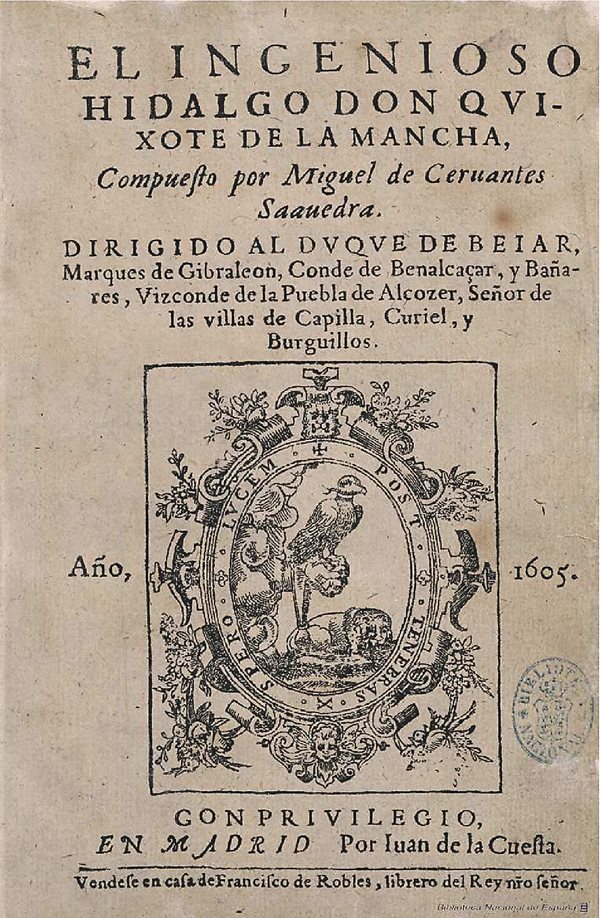

Published in two parts, in 1605 and 1615, Don Quixote was written during a turbulent era of deeply divided loyalties. After the Nasrid emirate of Granada, the Iberian peninsula’s last Islamic kingdom, fell in 1492 to Spain’s King Ferdinand ii and Queen Isabella i, Muslims were initially promised they could continue their way of life “para siempre jamás,” (“forever and ever”). But following local uprisings provoked by forced conversions and public burnings of the Qur’an, the Crown reneged.

Calamitously and practically overnight, Islam, Muslim dress, the Arabic language and even Arab names were outlawed. Muslims faced baptism as Christians, or exile. Many acquiesced to the former. They became “New Christians” and were labelled Moriscos, a pejorative indicating not only a former Muslim identity, but also inferior social status. Others defied the edict to varying degrees, outwardly professing conversion while covertly practicing Islam. These “crypto-Muslims” became a leading target of the church’s Holy Office of the Inquisition, established under Ferdinand and Isabella. A second Morisco rebellion, from the Alpujarras mountains, in 1568 was brutally crushed and, in its aftermath, some 80,000 Moriscos were forcibly relocated north, mainly to the provinces of La Mancha, New Castile and Extremadura.

“The official way of thinking was that Moriscos were traitors and that they were hiding their religion and culture from the authorities,” says Fernando Luis Fontes Blanco, director of Toledo’s Museo de Santa Cruz. “On the other hand, there was a lot of tolerance of the Moriscos, especially in La Mancha, where many Morisco families were able to integrate into society.”

At the same time, Spain was jockeying for New World dominance against a host of Old World colonialist rivals including England, France and The Netherlands, while waging war on European soil against all three. To the east, Spain faced Ottoman encroachment and hostility, especially to its maritime trade interests in the Mediterranean. The Crown’s fears of collusion (not entirely unfounded) among the Ottomans, European Protestants and aggrieved Moriscos meant the latter became an even greater target of suspicion and bigotry. This gave Spanish Christian nativists opportunities to spread rumors that all Moriscos not only imperilled national security but also threatened to overwhelm Spain’s Cristiano Viejo (Old Christian) majority and contaminate what they believed to be its purely Spanish-Christian limpieza de sangre (purity of blood).

During his years in captivity … [Cervantes] had the opportunity to get to know first-hand the life and customs of the Ottomans, of the Moors, of the Jews, of the renegades.

—Celsa Carmen Garcia Valdés

Like the times he lived in, Cervantes’ own relationship with Islam, Moriscos, and the idea of limpieza de sangre was complicated. He was born in 1547 in the university town of Alcalá des Henares in Castile, about 35 kilometers northeast of Madrid. He achieved fame, though not necessarily fortune, as a freelance writer, poet and playwright. Freelance writing being what it is and always has been, he supplemented his income with stints as a farmer, accountant, bureaucrat, and tax collector, most of which proved dead ends. If there was one endeavor at which he excelled, aside from writing, it was doing time in jail.

In 1575, after fighting the Ottomans in the Mediterranean crippled his left arm, Cervantes was captured by Barbary pirates. He endured five years in prison in Algeria, where he was beaten, tortured, and, after numerous unsuccessful attempts at escape, eventually ransomed and released. Yet in Algiers he also experienced another layer of multiethnic, multicultural existence, one in which Muslims, Jews and Christians were more or less coexisting—in contrast to what was happening back home in Spain.

“During his years in captivity … [Cervantes] had the opportunity to get to know first-hand the life and customs of the Ottomans, of the Moors, of the Jews, of the renegades (and) of the Christian prisoners,” observed the University of Navarra’s Celsa Carmen García Valdés in her 2005 article, “Life and Literature: Tolerance in Cervantes’ Work.”

Back in Spain, Cervantes was jailed for embezzlement, a relatively understandable offense since skimming off the top was often the only way a collector of royal taxes could get paid. In between jail and work, he wandered: Rome, Madrid, Valladolid, and Esquivias in Castile-La Mancha, where he lived on his wife’s family farm with Moriscos as neighbors. He also spent time in Seville, where, in addition to working as a purchasing agent for the Armada, it is also said he began to write Don Quixote—in jail.

It was written to appeal to the maximum number of people and offers a positive, sympathetic view of those on the margins of society.

—Jose Manuel Lucia Megias

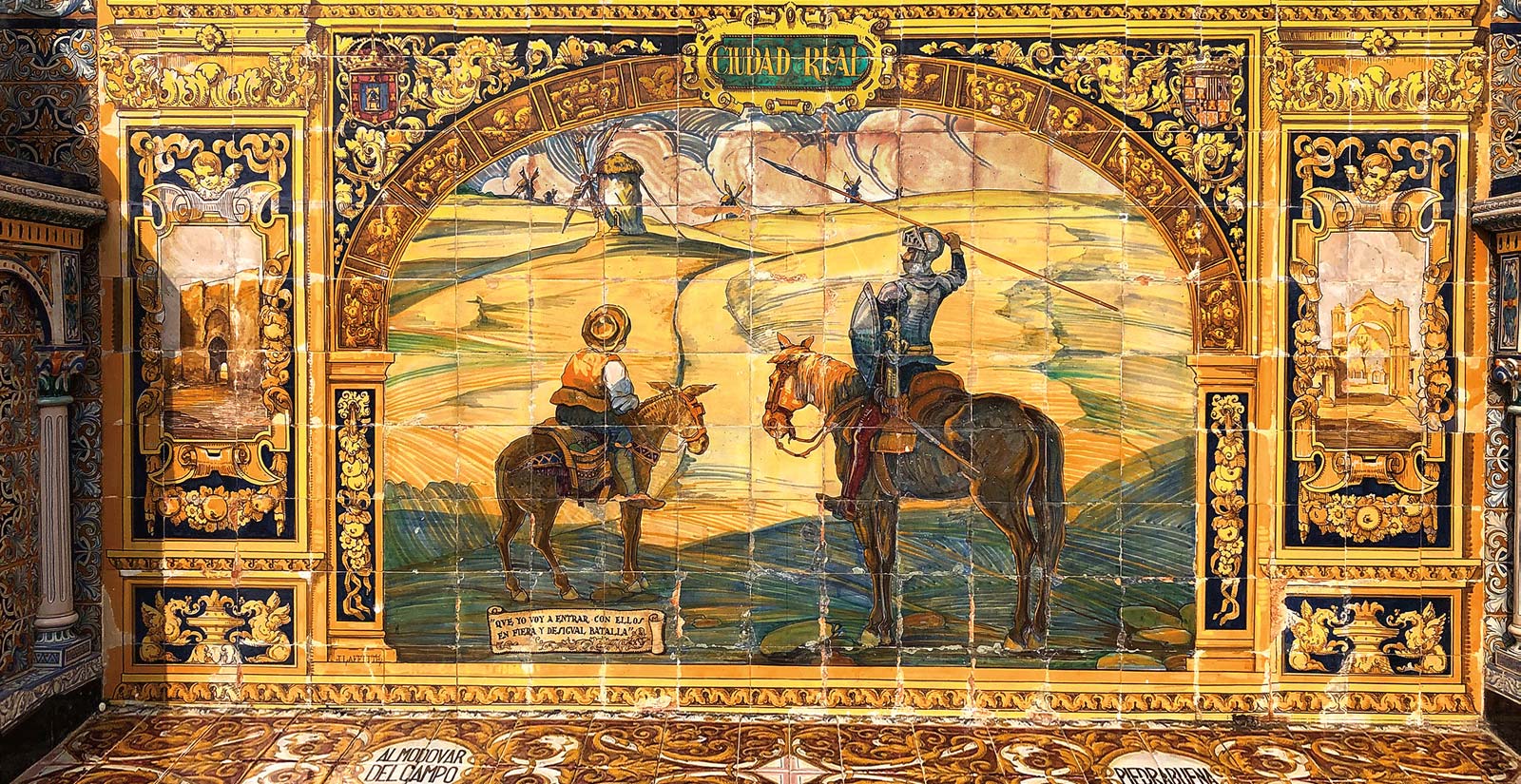

Gracious palm trees now shade a nearby bust of the author clutching a manuscript on which is inscribed the novel’s memorable opening line, “En un lugar de La Mancha” (“Somewhere in La Mancha”). I gave the statue a respectful nod on my way to meet with the University of Seville’s professor of Arab and Islamic Studies, Rafael Valencia, one of Spain’s most eminent scholars of al-Andalus. (Tragically, Valencia suffered a fatal heart attack just four months later.) We sat in a cafe sheathed in vibrant azulejo tiles, boisterous testaments to the city’s historic fame as a pottery and ceramics center. Traditionally produced by Moriscos just across the Guadalquivir River in Triana, a busy commercial neighborhood, the tiles harken back to the multiculturalism of al-Andalus.

“An important thing to understand is that Cervantes and Don Quixote were living among two worlds. On the one hand, Don Quixote is the most Christian, the most Spanish figure in Spanish literature, but he is also the most open to the Moors, to the Arabs,” says Valencia.

Cervantes, like his characters, may have occupied two worlds himself. Scholars speculate that he was perhaps of Converso ancestry. Even though he was a devoted Catholic, the Cervantes name was among those discovered in an official 15th-century document listing families with Converso bloodlines. His grandfather’s work in the cloth industry and his father’s profession as a barber and surgeon put them among trades dominated first by Jews and subsequently by Conversos. This background may have stymied Cervantes’ career, at least in the civil service, where ancestry carried political clout. Thus, his obsession with limpieza de sangre and the challenges and frustrations of what it is to live outside looking in—be it as a Converso, a Morisco or a silly old man who thinks he is a knight in armor—became important subtexts of Don Quixote.

“When the Moriscos were expelled by Philip iii, Cervantes had to take the official position that they needed to be expelled. He never publicly objected to the edict. But secretly, he felt sorrow and sympathy for them,” says museum director Fontes Blanco.

When viewed from this angle, the dualities running throughout Don Quixote—where windmills are giants, country inns are castles and barber’s basins are magic helmets—shift from comic effects to social commentaries. Like the Moriscos, crypto-Muslims or any of those whose pedigrees were iffy, Cervantes, on a personal level, was aware of what it was to inhabit multiple worlds in an era dominated by a monolithic and orthodox Hispano-Christian ruling class that called all the shots. And what’s more, he decided to push back.

“What is original, what is the genius of Don Quixote, is that it wasn’t a work devised to protect the prerogatives of those in power. It was written to appeal to the maximum number of people and offers a positive, sympathetic view of those on the margins of society,” said Cervantes scholar Jose Manuel Lucia Megias, professor of philology at the Complutense University of Madrid.

In Part Two of the novel, Cervantes dedicates Chapter 54 to Moriscos, a chapter he composed even as the convulsive deportations were still taking place. Ricote, a wealthy Morisco and former neighbor of Don Quixote’s companion Sancho Panza, has been expelled from the country, but he returns in disguise to retrieve some buried treasure he was forced to leave behind in Spain. (Again, Cervantes is playing with the names and language: Ricote translates as “rich man.”) Ricote is noticed by Sancho, who embraces him and expresses concern for his safety. “[I]f they catch and recognize you, it will go hard with you,” Sancho warns his old friend. Later, Ricote tearfully recounts the injustice of the expulsions.

“You know very well, O Sancho Panza, my neighbor and friend, how the proclamation and edict of His Majesty issued against those of my race brought terror and fear to all of us,” Ricote says. Yet despite the harshness of the edict, he concludes: “No matter where we are, we weep for Spain, for, after all, we were born here, and it is our native country.”

Cervantes’ road-trip duo discovers common ground by journeying together and, most importantly, listening to one another along the way.

As he speaks, Ricote gives voice to the hundreds of thousands of Moriscos who were similarly banished from what they considered to be their ancestral homes, an injustice Cervantes went out of his way to call out.

“Ricote is not necessary to the plot of the story, but Cervantes put him in there because he wanted to address the positive aspects of Moriscos, who have an important presence in the novel,” said Megias.

But with the Inquisition looking over the shoulders of writers during his era, Cervantes had to choose his words carefully to portray Moriscos in any positive light, often relying on double entendre and subtle, inside jokes.

When introducing us in Chapter 1 to the character of Alonso Quijana, the aging hidalgo whose immersion in too many “books of chivalry” delude him into believing he is a knight—Don Quixote de La Mancha—Cervantes catalogs the old fellow’s humble diet: hash most nights, the occasional stew, lentils on Fridays, and, on Saturdays, duelos y quebrantos.

This last phrase has posed particular challenges to translators. Literally, it means “trials and sorrows” or “trials and wounds,” of which Don Quixote certainly had his share. But it has also been variously interpreted as “scraps,” “tripe and trouble,” and “eggs and abstinence.” This last translation references Saturday Christian semi-fasts in Spain that commemorate the Spanish defeat of the Muslim Almohads at the Battle of Navas de Tolosa in 1212, which marked the beginning of the Christian Reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula from Muslim rule.

Yet, as scholars believe Cervantes was keenly aware, among Moriscos and Conversos, duelos y quebrantos, in the sense of “trials and sorrows,” was also a euphemism for bacon (or ham) and eggs. This staple fare among Christians in La Mancha was used as a way to force Moriscos and Conversos to prove the sincerity of their conversions by eating the dish in public—or face the Inquisition.

Such issues were on the mind of chef Paco Morales in 2016 when he opened the Noor restaurant in Córdoba. Offering diners modern interpretations of historic Andalusian dishes, the ingredients on Morales’ carefully curated menu all date to an age when what you ate (recall Cide Hamete’s cultural identification as an “eggplant eater”) pinpointed who and what you were.

“Food was an important part of culture and a way to manifest religious beliefs,” Morales said as I sampled delicate eggplant fritters with cane honey, sautéed spinach and sheep-milk cheese with basil, and an emulsion of pistachio, smoked herring roe and green apple. While it all tasted heavenly now, it was the “devil’s food” to the Inquisition owing to its historically Muslim associations.

“For example, we have on the menu a dish called caldillo de perro that in English means ‘dog gravy.’ This sauce, made with whiting and bitter orange, got this name because it was eaten by Muslims who the Christians called ‘dogs,’” Morales said.

Moriscos indeed had to publicly endure duelos y quebrantos of many kinds. When the Morisco translator in Toledo’s Alcaná randomly opens the pages of the manuscript by “Cide Hamete” and begins to translate for the first-person narrator, he is amused at a notation in the margin about one Dulcinea of Toboso. This is the high-society lady whom Don Quixote, in his distracted mind, has fabricated from the true object of his affection, a peasant woman named Aldonza Loronzo.

“This Dulcinea of Toboso … they say has the best hand for salting pork of any woman in all of La Mancha,” the Morisco reads aloud with a chuckle. The inside joke here is that Dulcinea/Aldonza is actually a Morisca whose reputation at curing ham was her way of deflecting suspicion away from her Muslim ancestry.

Toboso was one of the many towns in Castile-La Mancha where significant numbers of relocated Moriscos settled in the wake of the 1568 rebellion. Once a busy commercial crossroads, today it is a sedate, agricultural town surrounded by livestock and vineyards. Dulcinea may have been based on the real-life Doña Ana Martínez Zarco de Morales, whose stately, 16th-century farmhouse is now the Dulcinea del Toboso House Museum, where Fontes Blanco also serves as director.

On a tour through the meticulously restored villa, filled to its exposed wooden ceiling beams with authentic 17th-century furniture, he guided me to the estrado on the second floor, where ladies of the era would have gathered to talk, read, sew, and simply pass time sitting on a broad, raised platform strewn with pillows and Oriental rugs. It all still looks very Arab.

“It was a very important part of the house,” Fontes Blanco said. “Even as late as the 18th century in Spain, women sat in the Muslim fashion on carpets and cushions on the floor.”

On the one hand, Don Quixote is the most Christian, the most Spanish figure in Spanish literature, but he is also the most open to the Moors, to the Arabs.

—Rafael Valencia

Don Quixote also enables Cervantes to probe contemporary, often paradoxical attitudes toward Islam, Islamic culture and Moriscos. Idealized stories and ballads of noble, knightly “Moors” and their ladies from the medieval past—a genre collectively known as romancero morisco—were widely popular during Cervantes’ time, “even as Moriscos were increasingly persecuted,” Fuchs pointed out. Cervantes’ genius was to cash in on the familiarity of that genre while modernizing it and, along the way, demonstrating how fluid identities could be.

In Part One, Chapter 37, Cervantes introduces what is known to scholars as “The Captive’s Tale.” Perhaps the most autobiographical section of the novel, it tells the story of the fictional Ruy Pérez de Viedma, a Christian soldier who escapes an Ottoman prison in Algiers and returns to Spain with Zoraida, the daughter of “a wealthy Moor named Agi Morato.” Agi Morato was based on Cervantes’ own experience with the real-life Haci Murad, a renegade Dalmatian Christian who rose to power through service to the Ottoman sultans in Algiers and who was instrumental in saving Cervantes’ life. Murad’s real daughter Zahara never eloped with a Christian captive—let alone Cervantes himself—but she did marry Abu Marwan Abd al-Malik, who was none other than sultan of Morocco.

Cervantes writes that Viedma, wearing a “short blue woollen tunic … breeches of blue linen … ankle boots the color of dates and a Moorish scimitar” strapped across his chest—enters a tavern with Zoraida, who is similarly dressed in Muslim attire, “her face hidden by a veil.” He speaks to her in Arabic, but she knows enough Spanish to declare that now that she is on Spanish soil, she wishes to be addressed as “Maria.” When questioned by the innkeeper’s wife if she is Muslim or Christian, Viedma responds that she is a “Moor in her dress and body” but in her soul desires to become a Christian, and has delayed her baptism because she has not yet been properly instructed in “all the ceremonies” required for the service.

Here Cervantes jabs at the hypocrisy of both church and state: When Muslims were forced to convert, many were simply rounded up and baptized in churches (many of which were formerly mosques) with little or no theological instruction in the Christian faith. Under such circumstances, conversion rings hollow. Furthermore, if society can find a place for “the exotic Zoraida,” as Fuchs observed, “whatever her ethnic and cultural differences,” then it can surely find room for the far more proximate Moriscos who were at the time being herded onto ships and deported.

This episode is one of many throughout the novel that emphasize why dialogue, said Megias, is a key to understanding Cervantes and his most famous characters, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. They are figures from different classes and backgrounds, one educated, one not; one practical-minded, one not so much, who nonetheless find common ground by journeying together and, most importantly, listening to one another.

“Don Quixote is a minor noble who reads books. Sancho Panza is a laborer who has never read a book in his life, and whose understanding of the world comes from street smarts,” said Megias.

But as the novel progresses, they are each transformed. As they travel through the Spanish countryside, Sancho learns from Don Quixote just as if he were reading a book, and Don Quixote learns from Sancho what he would never find in his library.

What Cervantes is telling us, in an unintentionally modern way, said Megias, is that “change happens when we are willing to listen to and can accept and look positively upon someone who is different from you. And that’s why people of other cultures and other times have been able to read and identify with this book.”

The author gives special thanks to Duane Alexander Miller for research and translation and to Ana Carreño Leyva for logistical support.

You may also be interested in...

Covering 75 Years of Arts & Culture

Arts

Sharing connections in the arts and cultural heritage is reflected in AramcoWorld's cover stories about architecture, visual arts, photography, music, literature and more.

A Life of Words: A Conversation With Zahran Alqasmi

Arts

For as long as poet and novelist Zahran Alqasmi can remember, his life in Mas, an Omani village about 170 kilometers south of the capital of Muscat, in the northern wilayat (province) of Dima Wattayeen, books permeated every part of his world. “I was raised in a family passionate about prose literature and poetry,” Alqasmi recalls.

Celebrating 75 Years of Connection Stories and Culture

Arts

History

Since its origins in 1949 as a company newsletter for Aramco, AramcoWorld has evolved to focus on global cultural bridge-building across the Arab and Muslim world and beyond.