Could Phoenicians Have Crossed the Atlantic?

- Arts

Written by Tristan Rutherford

Photographs by Yuri Sanada

For the better part of a thousand years, all over the Mediterranean Sea, one power dominated maritime commerce: Phoenicia. Based along the coast of what is today Syria, Lebanon and northern Israel, Phoenicians wrote down much less of their own history than did the Romans, who gradually overwhelmed them by around 200 BCE. In addition to advances in boatbuilding and navigation, Phoenicians pioneered the production of metals and blown glass, and they were most famous for making purple dye from the murex seashells that could be found on the eastern shores of the Mediterranean. Their network of ports, trading stations and city-states included locations all over the Mediterranean and along the Atlantic coasts of what are now Morocco, Spain and Portugal. There is evidence also attributed to them even farther, in the Azores as well as in coastal France and the UK, leading some to the question: Did the Phoenicians discover the Americas?

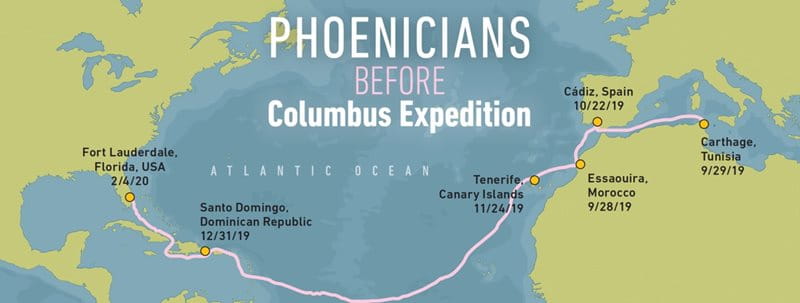

In late 2019 a crew of 30 explorers, hailing from as far afield as Norway, Indonesia, Tunisia, the UK, US and Canada, set out to demonstrate that 1,000 years before the Vikings and some 2,000 years before Columbus, Phoenicians had the ability to also reach the Americas. The crew sailed a replica, single-mast Phoenician ship, built in Syria and captained by a Briton, while being filmed by a Brazilian of Lebanese descent. Braving sharks, storms, fickle winds and looming container ships, they docked Phoenicia in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, five months after departing Carthage, Tunisia, once the leading Phoenician port in the central Mediterranean.

The Phoenicians Before Columbus Expedition was captained by Philip Beale, who had already smashed a couple other historical, maritime presumptions. In 2003 the former Royal Navy sailor recreated an eighth-century-CE double outrigger based on a temple relief in Java, Indonesia. Sailing the “cinnamon route” from Southeast Asia to the Seychelles, Madagascar and mainland Africa, Beale’s Borobudur Ship Expedition successfully challenged the idea that Europeans had been the preeminent explorers of the Indian Ocean. In 2008 he led Phoenicia on its two-year maiden voyage: a westward circumnavigation of Africa that corroborated Greek accounts of such voyages by Phoenicians.

Crossing from the Mediterranean to the Americas, Beale believes, would have posed little problem for Phoenician seafarers.

“Phoenician boats sailed easily from Tyre and Sidon,” two leading Phoenician cities that produced murex purple dye, both now in modern Lebanon, to Gibraltar and Tangier, says Beale. “That 2,000-odd-mile voyage is about the same distance as across the Atlantic.”

Beale points out that first-century-CE Greek historian Strabo estimated that beyond the Strait of Gibraltar, the Phoenicians had some 300 settlements along the Iberian and African coasts.

Greek historian Strabo estimated Phoenician settlements on the African and Iberian coasts numbered 300.

“Even if that figure was an exaggeration,” Beale says, “that’s a lot of contacts not to have sailed out into the Atlantic.”

There also may also have been serendipity—or catastrophe—at work. Phoenician boats were square-rigged, which means they could sail only with the wind. By the time of Columbus, Europeans were rigging their boats with one or more types of triangular lateen sails, which had been developed by Arab mariners in the seventh century CE. The shape of the lateen sail allows it to act like an airfoil when it is turned at an angle toward the wind. Here is Beale’s key point: “A modern yacht can sail 30 degrees into the wind,” Beale says. “But on a 2,600-year-old boat, once you’ve been pushed out into the Atlantic, you can’t come back” until the wind shifts. And amid the Atlantic, that can be a long time.

The captain also cites the relatively recent discovery of the Viking settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, Canada, as evidence of other pre-Columbian voyages.

“The proof that the Vikings arrived about 1000 CE was only discovered in the 1960s,” says Beale, and it was backed up in 2016 by a replica voyage in a hand-built Viking longship from Norway to Newfoundland.

While settlement evidence supports Viking arrival in the Americas, to date archeologists have found no material evidence that points toward Phoenician landings. For Beale there was only one immediate way to test the hypothesis that Phoenicians too could have beaten Columbus: Sail a carbon copy of a 2,600-year-old Phoenician trading ship from the Mediterranean to the Americas.

That meant, first, locating a sufficiently intact Phoenician ship to replicate.

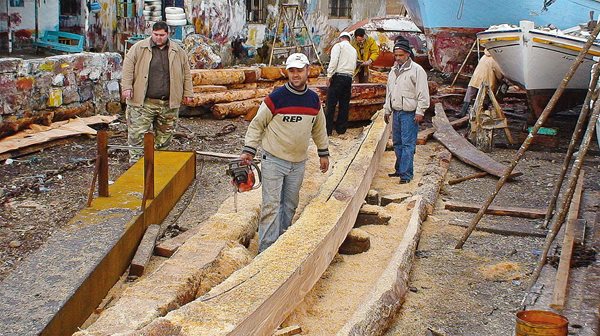

“Building the ship in the ancient Phoenician way was a difficult task, but we were full of enthusiasm.”

—Khaled Hammoud

“We wanted one dated around the sixth century BCE,” explains Beale. That was when the historian Herodotus, also Greek, recorded the most far-reaching known Phoenician voyages, including those around Africa.

Beale’s network of contacts elicited a call from maritime expert Harry Tzalas of Greece.

“He started by saying, ‘We know about the Jules Verne 7,’” Beale says, a Phoenician trading vessel newly discovered in good condition on the seabed off Marseille in southern France. Beale adds, still quoting Tzalas, “‘The wreck has not been published yet. But we can get you access.’”

Jules Verne 7 proved the perfect model, dating to exactly the period cited by Herodotus. Its planks had been dovetailed together using mortise-and-tenon joints made from olivewood pegs, a technique of joinery that was known by the Romans as a coagmenta punicana (Phoenician joint). It’s still used in shipbuilding and carpentry today. More importantly Jules Verne 7 is “probably still the only Phoenician wreck that’s been excavated and lifted from that period,” says Beale, mentioning that Marseille served as a significant Phoenician trading center, along with Cádiz in Spain and Carthage, just north of Tunis in Tunisia.

“It is considered a hereditary profession,” says Hammoud. “Building the ship in the ancient Phoenician way was a difficult task, but we were full of enthusiasm,” he says. “In Syria there is still the appropriate wood that was used to build Phoenician ships,” including Aleppo pine, cypress and cedar, as well as olivewood for the thousands of pegs that secured the planks.

“If anyone could have done it before Columbus, it was the Phoenicians.”

—Captain Philip Beale

In 2008, crowds lined Arwad’s stone quays to cheer on the departure of the ship—with with her purple-striped, rectangular sail—as it embarked on her maiden voyage, around Africa. Eleven years later, in September 2019, the scene was similar as spectators, some in period costumes, and members of the heritage group Club Didon de Carthage joined Tunisian government ministers to wave off Phoenicia once more, this time as it set a westward course for the Dominican Republic, the country in which Columbus had first come to shore.

On board also was environmentalist, diver, film director and Explorer’s Club member Yuri Sanada, who came with his own Phoenician history: Along with 6 million fellow Brazilians, Sanada claims Lebanese descent.

“My grandfather was from Bechara in the Mount Lebanon Range, where you have the cedar trees,” he explains.

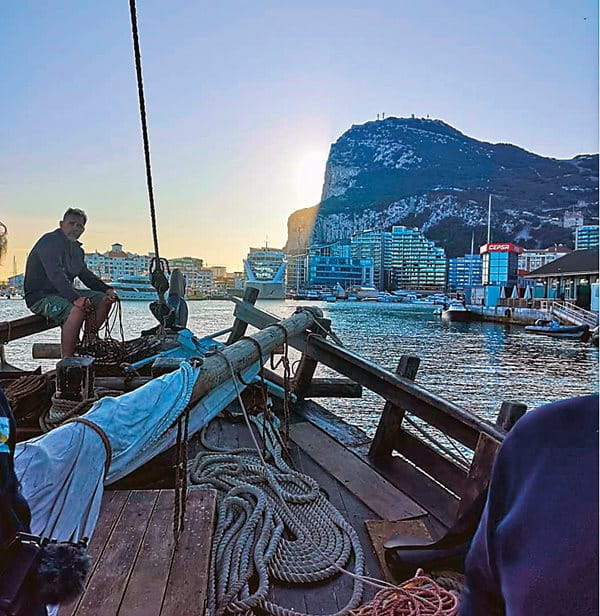

Sanada had sailed on Phoenicia’s Africa voyage, and he was equally keen to understand whether early civilizations could also have sailed to his native hemisphere. He soaked in the many cultural connections in Phoenicia’s ports of call on the way, each place a part of the Phoenician trade network. Phoenicians were the first to bring olive oil to trading posts like Cádiz, as well as to Sicily, Malta and into the Black Sea. Everywhere they went, Phoenicians had standardized the sizes of their amphora jars—the shipping containers of their day. Standardization added confidence to purchases ordered from other trading stations, as buyers could trust the quantity they paid for. In another seagoing first, the Phoenicians invented maritime insurance: If merchandise was lost at sea, other shipowners would contribute toward the shortfall. This encouraged more far-reaching, risky—and sometimes more rewarding—voyages.

For Sanada and the rest of the crew, life aboard Phoenicia was never dull.

Other days the sea was quiet and the days pleasant.

“With the ship becalmed, we’d often do some swimming,” he says. “Until somebody on deck saw a shark.”

Another port of call was at Essaouira on Morocco’s Atlantic Coast, where in centuries past Phoenicians had found another source of murex sea snails and set up a trading center to manufacture purple dye. Essaouira’s ruins may also have kept papyrus trading manifests written in Phoenician, the world’s first phonemic script and the first form of writing that would have been widely available to maritime merchants. Prior to the rise of the 22-letter Phoenician alphabet, writing involved clay tablets—not a particularly suitable medium for an essentially wet business—or hieroglyphs, whose numerous characters made them the script of elites, not merchants. Phoenician letters inspired both the Greek and Aramaic alphabets, as well as roots of both Hebrew and Arabic scripts.

Phoenicia’s final stop before crossing the Atlantic came on the island of Tenerife in the Canary Islands. Here the Phoenicians had found more murex—so much that they nicknamed the archipelago the “Purple Isles,” and they left pottery behind.

“It was like a one-way ticket. You can only sail with the wind behind you. There was no turning back.”

—Yuri Sanada

Firm evidence proved Heyerdahl’s theory seven decades after his expedition. In 2020 the scientific journal Nature published results of studies showing that DNA of South Americans had been woven into that of communities on Easter Island and other Polynesian islands somewhere between 1150 CE and 1230 CE.

Similar genetic studies may also help add evidence to the Phoenician question, where some research has made claims of pre-Columbian links between people from the Levant and Cherokee tribes, which lived mostly in what are now the coastal states of North Carolina and Georgia.

The Canary Islands also served as the port of departure for Christopher Columbus, as well as countless Spanish ships that followed. For Phoenicia, Sanada explains, when they unfurled their square sail off Tenerife, “it was like a one-way ticket. You can only sail with the wind behind you. There was no turning back.”

And danger was ever-present.

“We had some close calls with big container vessels, which move at 20 knots,” explains Sanada. Even though Phoenicia was outfitted with electronics to automatically transmit location, direction and speed to ships in the vicinity, “Phoenicia was visually very small. Sometimes you are moving at 1 knot.”

Currents and favorable winds usually allowed the vessel to average around 4 knots, with an occasional run of 7 knots, “which was supersonic for us,” Sanada says.

One of his most memorable moments, he says, came in the mid-Atlantic when the crew spotted a pod of 20 pilot whales. Sanada donned his mask and jumped in to join them.

“I swam within 3 meters of one whale. It looked right into my eyes,” Sanada remembers.

As a filmmaker he would also circle his drone camera overhead and around the vessel.

“Just a tiny ship moving through the waves,” he says.

A larger and less visible danger provided Phoenicia with a secondary mission. As part of the expedition’s partnership with the United Nations Clean Sea Campaign, each afternoon Sanada reached below the waves to collect a seawater sample and seal it in a vial marked with date, time and location coordinates. The Unicamp University in Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil, has offered to analyze the samples to track the levels of unrecycled microplastics at each point of the Phoenicia’s uniquely slow voyage.

On December 31, 2019, around 2,500 nautical miles and 39 days from Tenerife, the purple-striped sail of Phoenicia reached Santo Domingo harbor in the Dominican Republic. (Columbus took 36 days.) The ship’s log notes that Santo Domingo’s Lebanese-Syrio-Palestino Club welcomed and entertained the elated, exhausted crew. The Phoenicia sailed on to round Cuba, and on February 4, 2020, the crew docked it in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, where the boat awaits a permanent berth as part of a museum.

The question of Phoenician technical capability of reaching the Americas was no longer just a theory.

That leaves the question of evidence.

Archeologist Naseem Raad of the American University of Beirut uses archeology and marine science to understand human interaction with the sea. He is skeptical.

Raad points out that Phoenicia’s trading settlements in Spain and Northwest Africa generally include “evidence of shelter, pottery, a place to bury the dead, religious spaces,” and the like. No Phoenician evidence has been found anywhere in the Americas.

“There is evidence that Phoenicians did in fact make open-sea voyages and did not just hug coastlines,” he offers, adding that other types of Phoenician ships carried oars in case the winds died. This could be of help in areas like the Doldrums, the windless mid-Atlantic zone where sailing ships can remain becalmed for weeks.

For Raad the problem is motive.

“A transatlantic voyage doesn’t make sense financially,” he says.

The Phoenicians were commercially skilled sailors who “tried to maximize their cargo load. To have a large crew and extensive supplies for such a daunting journey would eat up space.”

Beale disagrees.

“I’m not saying there was a huge influence of the Phoenicians in the Americas, because there wasn’t,” he says. That’s because Phoenicians were sea traders, not colonizers like the Romans or the Spanish. Thus material evidence would be scant. In his opinion, that their brief visits did not result in stone temples or port constructions is about as important as the US landing on the Moon and not building a permanent base.

Sanada has a theory too.

“If Phoenicians arrived and found gold, the last thing they would do is shout about it,” he says. Instead, “they would spread rumors about sea monsters who would destroy your ship.”

The crew and ship of the Phoenicians Before Columbus Expedition showed that a transatlantic voyage was resolutely possible for Phoenicians. For now that is enough to add to an enduring historical question.

“If our volunteer crew could sail there, it would have been a walk in the park for the Phoenicians,” Sanada says.

About the Author

Tristan Rutherford

Tristan Rutherford is a 7-time award-winning journalist. His writing appears in The Sunday Times and the Atlantic.

Yuri Sanada

Environmentalist, filmmaker, television host and diving instructor Yuri Sanada is cofounder of Earth Odyssey and a Fellow Member of the Explorer’s Club. He lives near São Paulo, Brazil, in a self-built, environmentally sustainable home.

You may also be interested in...

A Reimagined Islamic Garden

Arts

The second Islamic Arts Biennale (Jan 24-May 25, 2025) in Jeddah explores multicultural expressions of faith, healing, regeneration and an appreciation of beauty..jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5&cw=480&ch=360)

FirstLook: A Market’s Port of Call

History

Arts

After the war in 1991, Kuwait faced a demand for consumer goods. In response, a popular market sprang up, selling merchandise transported by traditional wooden ships. Eager to replace household items that had been looted, people flocked to the new market and found everything from flowerpots, kitchen items and electronics to furniture, dry goods and fresh produce.

A Life of Words: A Conversation With Zahran Alqasmi

Arts

For as long as poet and novelist Zahran Alqasmi can remember, his life in Mas, an Omani village about 170 kilometers south of the capital of Muscat, in the northern wilayat (province) of Dima Wattayeen, books permeated every part of his world. “I was raised in a family passionate about prose literature and poetry,” Alqasmi recalls.