Pakistani Art Trucks on a Bridge of Culture

- Arts

12

Written by Dianna Wray

Photographs courtesy of Art 120

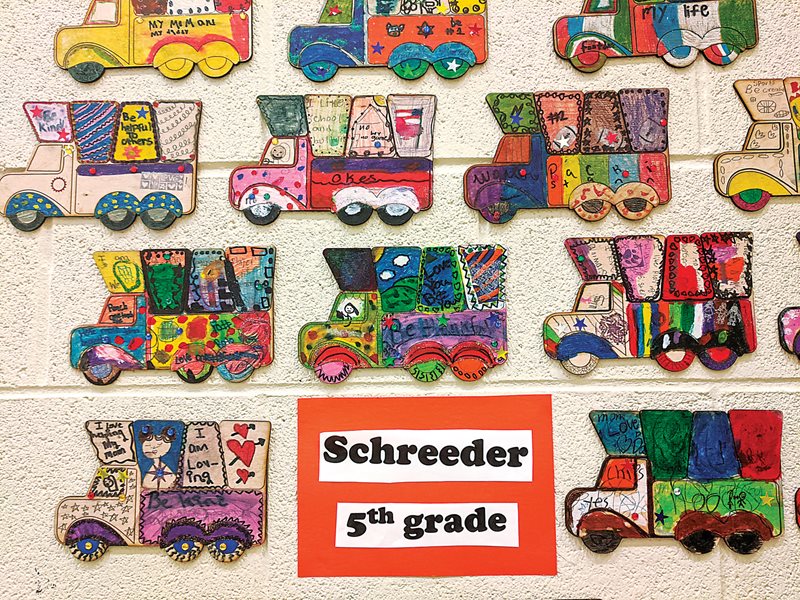

On one of the last few clear winter days in early 2020, only weeks before the global pandemic began to shutter educational institutions worldwide, a clutch of students from Orchard Knob Elementary in Chattanooga, Tennessee, approached a vibrantly painted Chevrolet truck. Bouncing on the balls of their feet, students waited in turn to climb up on a stool to better see two enormous owls emblazoned on the pickup’s hood ringed by pink and magenta roses and intricate geometric designs.

Standing alongside the once-white utility truck, which she had commissioned world-famous Pakistani truck artist Haider Ali, 41, to paint the year before, Kate Warren, founder and executive director of the Chattanooga-based nonprofit Art 120 and creator of its year- old Jingle Truck Program, watched the children approach. The truck was the key to the entire program, an arts-based outreach Warren established with a grant awarded by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. But the truck art had been created in a world that bore little outward resemblance to the one these children inhabited, one of the poorest schools in the region, set down between the Tennessee River and the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. A quiet reticence loomed: Would the kids be open to it? Warren soon learned they would, indeed.

“It’s so pretty,” a girl in a raspberry pink sweatshirt whispered, her large brown eyes drinking in the creature painted with such care that it seemed almost possible either birds’ amber eyes might blink before the detailed feather-covered wings would flap it away from view.

“See the owls,” said Sadaf Khan, the lead instructor for the program, seizing on the moment to explain how truck art works, “how they are lined with orange? You can design anything.”

Watching the girl’s face, Warren began to relax. The first challenge was always simply getting the kids interested in the art. Now she and Khan, a local artist who immigrated to Chattanooga from Karachi, Pakistan, more than a decade ago, could move on to the larger challenge: helping students fully connect to this art form that has flourished in the country as a means of advertisement, celebration and self-expression.

Barely out of its first year, the Jingle Trucks Program flourished using lively, interactive, in-person approaches. Warren and Khan had no way of knowing that everything would be upended by COVID-19—and that circumstances would end up giving them the chance to reach even more children through equally creative approaches online.

The idea for Jingle Trucks, which has held roughly 20 events a year since its 2019 launch and has served more than 2,000 area students, stems from one of the darkest events in Chattanooga’s recent history: the 2015 fatal shooting of five US Marines and one Naval reservist by a young naturalized US citizen born in Kuwait to Palestinian parents. The shootings sparked anti-Muslim sentiment, and while Chattanooga’s mayor had already formed a civic council to address a rise in hate crimes, Warren pondered how she might help.

“I thought to myself that there was another conversation out there that we could be having about this,” she said. “I started looking for ways to do that.”

It was then she thought of Ali. Warren had worked for Watermark, one of the top art galleries in her hometown of Houston, Texas, where she had also developed ties to Houston’s art car scene, which boasts the US’s largest annual parade of ornately decorated vehicles. In 2011 she had brought the first art car to Chattanooga as a way of creating opportunities for connections between local artists and the rest of the town, just a year after founding the Chattanooga-based nonprofit Art 120. She began helping local artists visit schools to help students learn to express themselves through art cars, art bikes, and more.

Decorating modes of transport—from camel saddles to river boats—is a tradition that in Pakistan dates back centuries.

“I was amazed by it,” she recalled. “It looked unlike anything I had ever seen.”

An idea for a partnership began to take shape in her mind.

“I wanted to give kids an understanding of this culture that would focus on whole different aspect of this predominantly Muslim country,” Warren said. “Most of the children growing up here won’t get a more nuanced view of the country otherwise.”

The history of Pakistani truck art—known in Urdu as Phool Patti and dubbed “jingle trucks” only recently by US soldiers in the region—started in the 1920s with Bedford trucks that were imported from Great Britain, when what is now modern Pakistan had been under British rule for more than 60 years. The trucks soon became renowned, attaining popular cult status for their reliability, durability and power. The original truck featured only the cab, the chassis and the engine. The rest of it had to be added on, usually by means of wooden panels secured to each side, according to University of Karachi Professor Durriya Kazi, founder and head of the university’s visual arts program and an expert on the complex history of Pakistani truck art. It became standard to add on seven panels to the sides of the truck and a large wooden crown, called a taj, above the cab, with every visible part of the vehicle sporting some decoration.

In the 1940s, as the push for India’s independence from Great Britain and the movement for a postcolonial partition into two states increased, truck art continued to popularize along with the increasingly industrialized economies. It had been a natural artistic evolution, coming out of a long tradition of artists who specialized in painting shrines and palaces while others excelled at the intricate geometric patterns found in henna tattoos. Plus, there was an even older, millennia- long tradition of decorating your mode of transportation as a way of ensuring you would travel safely. “Transportation has always been a form of power and of superstition here,” Kazi said. “In the old days, other ways of getting around, from camel caravans to river boats, were decorated. So the tradition was already there. The bodies of the trucks were built here, and they were designed to be painted.”

Soon drivers began investing in their truck art, from local, rough-road rural delivery drivers to long-haul truckers traversing mountains deep into Afghanistan and Central Asia. They hired professionals, paying a significant portion of income to have the best artists create eye-catching creations to attract the attention of potential customers and bring the drivers luck and protection. “It grew out of Pakistan, out of the instability of the newly formed country,” Kazi explained. “When your country is very unstable and new, you don’t depend on the government or police for safety. You depend on prayers, on the fates, on luck, and that is all manifested in the truck art.”

By the 1990s when Ali was a teenager growing up in Karachi, truck painting was a viable career. His own father had been taught by pioneer truck artist Hajji Hussain, and Ali’s father made a good living painting politicians, animals and celebrities alongside jokes, talismans and the patterns of roses and shapes that together make the country’s truck art so distinctive.

Ali still resides in Karachi, and he has become an acclaimed truck artist since learning to paint at age 8. As he learned, he worked under his father as shagird, or apprentice, although he quickly became a Barae Ustaad ji, an experienced artist entrusted with painting images. In 2002 he painted a Bedford truck on the National Mall in Washington, DC, for the Smithsonian Institution, where it is now part of the museum’s permanent collection.

“I wanted to give kids an understanding of this culture that would focus on a whole different aspect of this predominantly Muslim country.”

—Kate Warren

When Warren approached Ali with her idea, he immediately agreed. Warren then enlisted the help of Sadaf Khan, who holds two bachelor’s degrees in art from the University of Karachi and taught art before moving to the US. Khan had been volunteering with Art 120 as a welding teacher since 2015. Warren knew that with Khan she would have someone on her team who could present the truck art and put it in the context of Pakistani culture. “I was thrilled,” Khan said. “I wanted to help bring the kids another view of my culture.”

Warren secured a grant through the Doris Duke Foundation’s Building Bridges program in 2018, which was aimed at increasing awareness of Islamic cultures throughout the US. This helped fund the program’s first truck, which Ali painted with animals native to Tennessee and Pakistan and scenes from Chattanooga and Pakistan such as the city’s Walnut Street Pedestrian Bridge and Pakistan’s iconic, sharply peaked mountain K2, the second highest in the world. The program emphasizes outreach in economically disadvantaged schools where students have less access to the arts.

“The kids had a lot of questions, not just about Pakistan, but about me. They wanted to know why I cover myself, what my family eats, if there is internet in Pakistan, if there are kings and queens,” Khan said, laughing at the memory. “It was beautiful. They were so curious, and once they knew they could ask, we really got to talk. And I was learning too. We were learning about each other’s cultures.”

Warren says the kids have started talking about their own cultural background, and some students even shared, shyly, that their own families were Muslim. “It has helped these kids talk about being Muslim in a way they otherwise wouldn’t have access to,” Khan said.

Once the pandemic halted in-person teaching, Warren and Khan joined the educational platform Nearpod, which supports Zoom and Google Meet. While in-person teaching is still better, she said, the program is now offered online and as a hybrid allowing the group to work flexibly depending on conditions. “Now we’re ready for anything,” Warren said, mentioning her excitement for being ready to reach deeply rural areas that previously were too distant to arrange programming.

“The main point I keep telling the classes,” she said, is that “we are all connected to each other, that we can connect with each other through art, and that’s part of why art is so important.”

You may also be interested in...

Polish Explorer's Manuscript on Arabia Helps Preserve Cultural Heritage

Arts

Nearly 200 years after his death, Polish adventurer and poet Waclaw Rzewuski’s manuscript documenting his experience in the Middle East has become important to advancing understanding of 19th-century Bedouin life and customs.

On the resilience of handicrafts in Bosnia-Herzegovina

Arts

The backstreets of Sarajevo’s old town are alive with the repetitive thud of metalworking. In this European capital, with its contemporary high-rise buildings and modern brands, you can still hear the heartbeat of tradition.

Moroccan Photographer Explores Oasis Culture at Sharjah Biennial

Arts

Moroccan photographer M’hammed Kilito explores richness of oasis culture at Sharjah Biennial