Spice Migrations: Cinnamon

- Food

- Arts

6

Written by Jeff Koehler

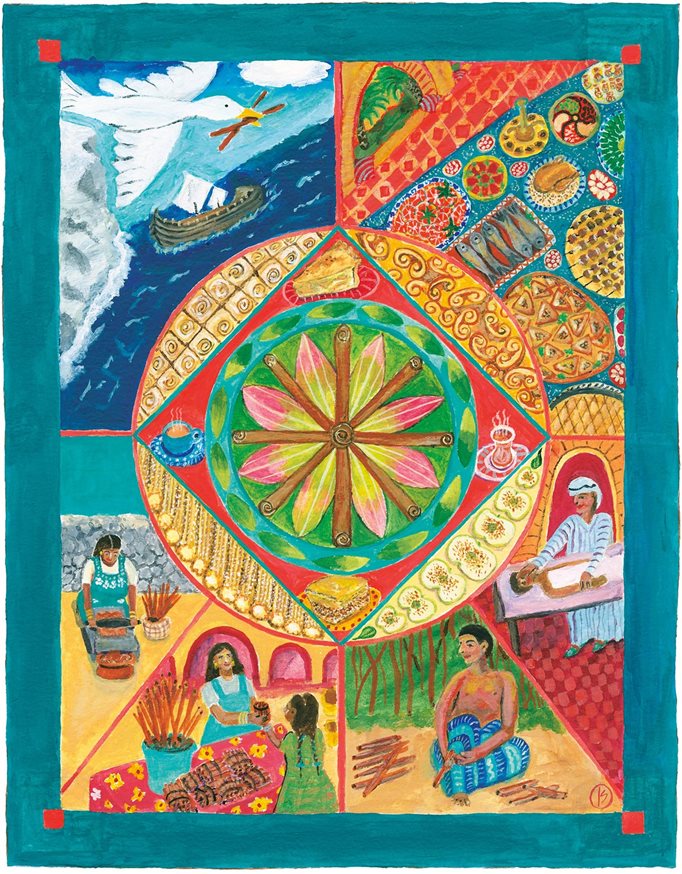

Art by Linda Dalal Sawaya

“The prince named Vijaya, the valiant, landed in Lanka,” recounts the Mahavamsa, the epic-poem history of Sri Lanka composed in the fifth century CE. Vijaya was, the account goes, expelled some 2,600 years ago from the Sinhalese royal court in India, and he sailed south from the Ganges Delta with some 700 soldiers. When he and the troops landed on the northwest coast of the island country, they “sat down wearied,” and their hands “were reddened by touching the dust.”

Vijaya called the kingdom he founded Thambapanni, “Copper-hands.” According to Sri Lankan historian Dilhani Dissanayake of La Trobe University in Australia, panni can refer also to leaves—specifically young leaves of the Cinnamomum verum (“true cinnamon”) tree native to that part of Sri Lanka.

An unassuming evergreen that, when cultivated, is a bush as much as it is a tree, says Marryam H. Reshii, author of The Flavour of Spice (Hachette India, 2017), cinnamon’s value lies not in its leaves, but in its inner layer of bark. The English word “cinnamon” comes from the Phoenician and Hebrew qinnamon, via the Greek qinnamomon, which may have come from a Malay word related to the Indonesian kayu manis, “sweet wood.” It’s the Greek that lends itself to the current botanical genus, Cinnamomum, of which verum is one of some 300 species. Cinnamon’s first scientific name, Cinnamomum zeylanicum, refers to Sri Lanka’s former name Ceylon.

Together with its close but coarser relative cassia (Cinnamomum cassia and several other species), which originated in southern China, cinnamon was carried to Egypt as early as 2000 BCE by merchants who, while trading throughout the Middle East and Arabia, kept their Sri Lankan source a secret. It isn’t surprising, therefore, that Greek historian Herodotus wrote around 430 BCE in The Histories that cinnamon grew in the land where Dionysus, the Greek god of harvest, was brought up—that is, somewhere to the east—and that it was gathered in Arabia. Arab traders, he wrote,

say that great birds carry these dry sticks, which we have learned from the Phoenicians to call cinnamon, and that the birds carry the sticks to their nests, which are plastered with mud and are placed on sheer crags where no man can climb up.

The merchants, he continued, set large chunks of raw meat near the nests of this cinnamologus, or cinnamon bird. “The birds swoop down and carry off the limbs of the beasts to their nests, and the nests, being unable to bear the weight, break and fall down, and the Arabians approach and collect what they want.”

A “fabulous story,” scoffed Roman naturalist and philosopher Pliny the Elder nearly 500 years later, told by traders to keep prices high and sources shrouded. And while Pliny was right—the world did value cinnamon for both rarity and mystery—scarcely anyone in the Mediterranean or Europe could answer where it came for nearly another 1,000 years.

While today cinnamon is on nearly every spice rack, and it is used mostly to flavor food and drinks, its history shows it has had a range of other, mostly health-related roles, as Jack Turner noted in his 2005 Spice: The History of a Temptation. In addition to Egyptians who used it as a perfume in embalming, the Bible’s Old Testament mentions it as an ingredient in anointing oil. From India to Rome people burned it in cremation. The voluminous 10th-century Kitab al-Hawi fi al-Tibb (Comprehensive book on medicine) by polymath al-Razi recommends cinnamon to help “prevent sweat from armpit and feet, so there will be no stink.”

Medieval Islamic physicians used cinnamon to treat wounds, tumors and ulcers. They influenced European physicians such as Italian Matthaeus Platearius, whose 12th-century The Book of Simple Medicines recommended cinnamon to help form scars on wounds and relieve ailments of the stomach, liver, heart and more. Dissanayake points out that in Sri Lanka the fourth-century CE medical books of King Buddhadasa introduced the cinnamon tree as a medicinal tree or herb and that, still today, Ayurvedic medicine prescribes cinnamon to aid digestion and oral hygiene.

It was not until the 10th century that glimmers of the connections between Sri Lanka and cinnamon began to appear. In Aja’ib al-Hind (Marvels of India), traveler al-Ramhormuzi wrote, “Among remarkable islands, in all the sea there is none like the Island of Serendib, also called Sehilan [Ceylon]. … Its trees yield excellent cinnamon bark, the famous Singalese cinnamon.”

By the 13th century, naturalist and geographer Zakariya ibn Muhammad al-Qazwini had written in Athar al-bilad (Monuments of the lands) that “the wonders of China and the rarities of India are brought to Silan. Many aromatics not to be found elsewhere are met with here, such as cinnamon, brazilwood, sandalwood, nard, and cloves.”

Ibn Battuta, the most well-known global traveler of his time, came to the island in 1344 CE and wrote—or perhaps exaggerated—that “the entire coast of the country is covered with cinnamon sticks washed down by torrents and deposited on the coast looking like hills.”

Hieronimo di Santo Stefano of Genoa, traveling in the late 15th-century, noted that “after a navigation of twenty-six days we arrived at a large island called Ceylon which grow the Cinnamon trees.”

Still, the origins of cinnamon did not become widely known until after 1505, the year a storm blew a Portuguese fleet to the shore of Sri Lanka. The Portuguese departed with nearly six metric tons of the spice that whetted their appetite for more. Over the next hundred years, variously through force and local alliances, they gradually took control of the centuries-long Arab and Muslim trade monopoly. A century later Ceylon’s king allied with the Dutch to evict the Portuguese, only to have the British wrest control near the end of the 18th century. However, by 1800, Cinnamomum verum transplants were thriving commercially in India, Java (now in Indonesia) and the Seychelle islands off East Africa. No longer as scarce, cinnamon’s value declined, on its way to becoming a worldwide grocery-store spice staple.

Now twice a year, after Sri Lanka’s big and then small monsoon seasons, when high humidity makes production easier, wrist-sized cinnamon trees are cut, and skilled cinnamon peelers trim the branches and scrape off the outer bark. With blade-sharp knives they loosen and then remove the delicate inner bark, often only about a half-millimeter thick. They pack the paper-thin curls inside one another to form dense, cigar-like quills that are dried, graded and cut into lengths.

Traditionally, a peeler passed down the skill to an apprentice. According to Dissanayake, who wrote her doctoral dissertation on the subject, it took five to seven years to master the art. “The peeling process is really intensive,” Dissanayake says. It “relies on local knowledge, expert skills, dexterity and patience.”

Both in quills (cinnamon sticks) or ground to powder, true cinnamon has a highly fragrant aroma with a warm, woodsy flavor that is simultaneously delicate and intense, and its aftertaste is sweet. While in European and American cultures cinnamon features frequently in cakes, cookies, candies and hot drinks, in Sri Lanka, where cinnamon is pervasive in the national cuisine, cooks often add a quill to fish curries, for instance, and elsewhere cinnamon frequently compliments savory flavors such as Moroccan lamb tagines (slow-cooked stews), Turkish pilafs and Middle Eastern meat dishes, as well as curry powders, masala spice mixes and the essential Chinese five-spice mix.

Often what is on the shelf today is not Cinnamomum verum, true cinnamon, but its cousin cassia, which now grows both in southern China and in other parts of South Asia, like Laos and Vietnam.

Easier and cheaper to produce, cassia’s inner bark is darker, coarser and thicker—often too hard and thick to pulverize or grind by hand using a mortar and pestle. Cassia can be more pungent because it contains tannins, those protective polyphenols that make our mouths rough and dry. “The cinnamon of Sri Lanka is stronger, more sweet and pleasing to the palate, and not woody at all,” says Reshii. That sweetness, she adds, is why true cinnamon is so popular in desserts, breads and puddings, while cassia is popular among cooks for main dishes, from curries to kibbeh, especially across Asia.

Cinnamon has long been a key part of Sri Lanka’s cultural identity, and today it is one of the world’s most popular spices, a key to every cook’s pantry.

About the Author

Jeff Koehler

Jeff Koehler is an American writer and photographer based in Barcelona. His most recent book is Where the Wild Coffee Grows (Bloomsbury, 2017), an “Editor’s Choice” in The New York Times. His previous book, Darjeeling: A History of the World’s Greatest Tea (Bloomsbury, 2016), won the 2016 IACP award for literary food writing. His writing has appeared in the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, Saveur, Food & Wine and NPR.org. Follow him on Twitter @koehlercooks and Instagram @jeff_koehler.

Linda Dalal Sawaya

Linda Dalal Sawaya (www.lindasawaya.com; @lindasawayaART) is a Lebanese American artist, illustrator, ceramicist, writer, teacher, gardener and cook in Portland, Oregon. Her 1997 cover story, “Memories of a Lebanese Garden,” highlighted her illustrated cookbook tribute to her mother, Alice's Kitchen: Traditional Lebanese Cooking. She exhibits regularly throughout the US, and she is listed in the Encyclopedia of Arab American Artists.

You may also be interested in...

A Life of Words: A Conversation With Zahran Alqasmi

Arts

For as long as poet and novelist Zahran Alqasmi can remember, his life in Mas, an Omani village about 170 kilometers south of the capital of Muscat, in the northern wilayat (province) of Dima Wattayeen, books permeated every part of his world. “I was raised in a family passionate about prose literature and poetry,” Alqasmi recalls.

A Fasting Journey Through Ramadan

Arts

What’s it like as a non-Muslim to fast during Ramadan? Writer Scott Baldauf shares his journey through the holy month where he uncovers resilience, empathy and the powerful unity found in shared traditions.

Sea Beans With Fava Beans and Dill

Food

This recipe serves up one of London-based food writer Sally Butcher's favorite lunches—a perfect mezze dish of beans.