Three kilometers long and less than one wide, the island of Pulau Rhun is so tiny, says Indonesian photojournalist Muhammed Fadli, that it doesn’t even appear on many older maps.

Ringed by reefs rough enough to shatter a ship, the volcanic atoll is the smallest and most isolated of the 11 Banda Islands, which cluster loosely amid the more numerous islands of the Indonesian province of Maluku (Moluccas). Collectively the Maluku Islands became known in the West as the Spice Islands, a maritime trading zone blessed with—and exploited for—its endemic, uniquely aromatic plants. In the Bandas, this mainly meant mace and nutmeg. And in Palau Rhun in particular, this led to a curious kinship with a very distant American island whose fortunes turned out very differently.

People in the Bandas today descend from traders, laborers and slaves who came to the islands both willingly and not, mostly from Mainland and Maritime Southeast Asia. Bandanese today refer to their islands as tanah banda (land of Banda) and tanah berket (blessed land). Legend has it that Banda islanders were the first in the Indonesian archipelago to become Muslims. In a report written in 1512, Portuguese pharmacologist Tomé Pires noted, “It is thirty years since they began to be Moors.”

Islam had come with sailors who had come looking to buy what Rizal (“Abba”) Bahalwan, owner of the hotel and restaurant Cilu Bintang Estate on Banda Neira, the largest of the Banda Islands, describes as the fragrant seeds of the yellow-orange fruit of the tall, willowy nutmeg trees, with their laurel-like leaves and bell-shaped flowers.

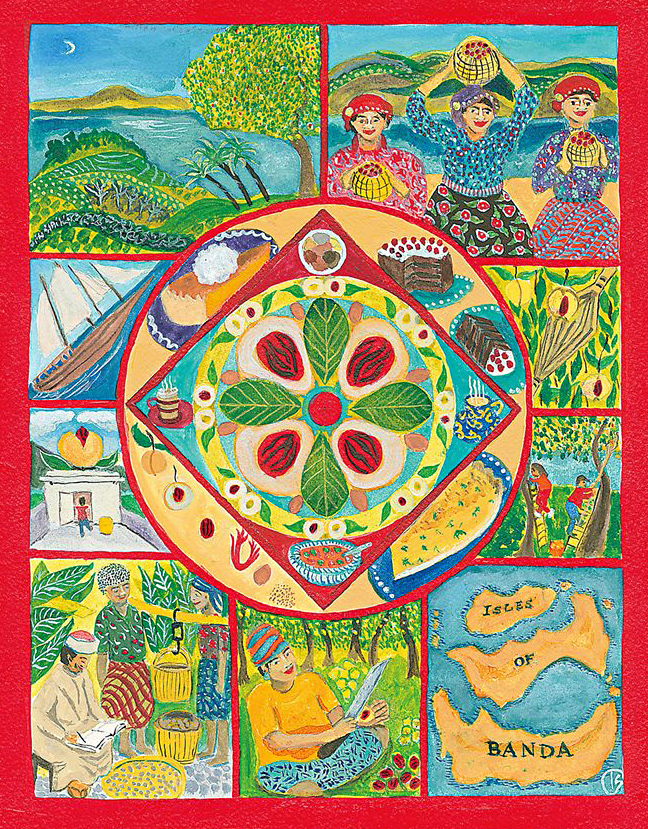

Bandanese, he says, refer to nutmeg as pala, a word derived from the Malayalam pāl and generally applied to many plants with a milky sap. Harvests of nutmeg come twice a year. Harvest workers use a gai pala (nutmeg picker), a wicker basket on the end of a long bamboo pole, to pull down the fruit that is, botanically speaking, a drupe. They then slice away the outer protective shell to reveal a glossy, dark-brown nugget wrapped in a bumapala, a saffron-red aril, or net-like caul: mace. It gets peeled away, dried, ground and sold as a separate spice.

The seed is the nutmeg.

“Nutmeg takes about a week and a half to dry, and the inner nut rattles,” says Bahalwan, a descendant of Arab spice traders who settled in Banda in the 17th century.

The unique flavor of the Banda nutmeg comes from volcanic soil, sea breezes and plenty of rain.

That was some 600 years after Arab traders first began taking pala to markets in China and Europe. They dominated the nutmeg trade during the Middle Ages, and though they guarded the location of their source, even by 1000 CE the polymath Ibn Sina (known in the West as Avicenna), who came from Bukhara in present-day Uzbekistan, identified nutmeg as jansi ban—“Banda nut.”

It was leaders called orang kaya who consolidated the nutmeg market and established commercial solidarity in the Bandas, which allowed the Bandanese to trade freely, Fadli says.

“The unique flavor of the Banda nutmeg comes from volcanic soil, sea breezes and plenty of rain,” says Bahalwan, who began working as a tourist guide at 15 years old in 1989. After attending the University of Pattimura on nearby Ambon Island, he returned to the Bandas, and in 2005 he opened his first guesthouse.

As nutmeg’s botanical name Myristica fragrans indicates, the spice is deeply, even profoundly aromatic. Arabic speakers refer to it as al-jouz al-tib (the fragrant nut). Nawal Nasrallah, food historian and author of the 2011 Delights from the Garden of Eden: A Cookbook and a History of the Iraqi Cuisine, describes nutmeg as having “a warm scent, pleasantly rich and woodsy in a very subtle way, and homey. It is inviting and does not overwhelm the senses.” Mace, she says, is “more playful, lighter, more feminine in nature, kind of addictive.”

As they did with many other spices, nutmeg’s earliest consumers often sought it out less for cooking than for medicine. Arab physicians initially promoted nutmeg as a curative-preventive aid against digestive issues and liver problems, freckles and skin blotches. In his highly regarded Al-Qanun fi al-Tib (The Canon of Medicine, 1025 CE), Ibn Sina recommended “three-eighths of a dram of nutmeg with a small quantity of quince-juice” for “weakness of the stomach,” and he included nutmeg in a potent anesthetic concoction.

Nutmeg found its way into kitchens, Nasrallah maintains, during Baghdad’s “Golden Era” of the five-century Abbasid caliphate, from 750 CE to 1258 CE. As metropolitan Baghdad became the world’s marketplace, so too did Arab cuisine flourish. “They had the means to experiment with all kinds of imported spices, including nutmeg,” she says.

Yet cooks continued to keep an eye on nutmeg’s health benefits. “From the extant medieval cookbooks we have, we can see that it was used more often in foods and preparations that were more medicinally oriented,” says Nasrallah by email. For example, in Kitab al-Tabikh, written in the 10th century CE in Baghdad by Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq and translated in 2010 by Nasrallah as Annals of the Caliphs’ Kitchens, “its usage with savory dishes is very limited, once in a sandwich preparation and a chicken dish. The rest are all foods and drinks made for their medicinal benefits, such as digestives, drinks, jams, etc., and hand-cleansing preparations.”

The Bandanese, long established as boatbuilders and mariners, controlled their mercantile interests through their orang kaya, who also sent crews to set up shop in spice markets as far as Melaka, some 2,000 kilometers away. From the early 15th century, the sultanate in Melaka developed the most extensive trade network the region had known. It was through active exporting by the Bandanese at the port in Melaka that nutmeg became a global commodity. According to maritime historian Chin-keong Ng, “islanders from Banda would row their boats laden with spices to cover the long distance.”

Despite global demand, nutmeg trees on the island remained largely inaccessible to all but those whom the Bandanese allowed to drop anchor. Others they drove off, including the first Portuguese, who showed up in 1511, the same year the Portuguese took control of Melaka. For several decades the Portuguese had to settle on sporadic visits to the Bandas and purchases from Bandanese coming to Melaka.

Nearly a century later, in 1599, the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC, or Dutch East India Company) muscled its way into the region. The Bandanese initially received the Dutch as potential allies against Portuguese encroachments, but they soon discovered that the Dutch were a far more powerful adversary. The Bandanese endured a Dutch campaign of deportations, executions and enslavement that came to a head in 1621 when the Dutch slew more than an estimated 90 percent of the population.

“It is hard to pin down the real number, because there are almost no records,” says Fadli, “but from approximately 15,000, only 1,000 or so survived.” This year, after a four-year collaboration with the Indonesian journalist Fatris MF, Fadli published a documentary project called The Banda Journal on the 400th anniversary of the massacre.

The Dutch took control of all the Bandas except isolated Pulau Rhun, which the English had taken. The VOC resettled the Bandas with settlers, slaves, convicts and indentured laborers from other parts of Indonesia and even India, thus seeding a new society in what became an agricultural colony of nutmeg plantations. Dutch attempts to transplant it outside the islands met with failure.

It was under these circumstances that Pulau Rhun became a powerful pawn in the Dutch-English rivalry over colonial resources, which erupted into war four times. The second of these conflicts settled in 1667 by the Treaty of Breda, named for a city in the Netherlands. Under Breda’s terms, England ceded Pulau Rhun, which gave the VOC a monopoly in the Bandas. In exchange, the Netherlands ceded a slightly larger, wooded island in North America that went by the Lenape name of Manhattan. The English gave a new name to Manhattan’s Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam: New York.

Back then, says Fadli, “no one would have imagined New Amsterdam would become this economic powerhouse. And if you see Rhun Island,” it is “really a backwater.” For Palau Rhun’s 2,000 people, electricity only runs a few hours in the evening, fresh water can be scarce, and many services basic to life on the other Bandas remain out of reach.

In 1667, however, the Dutch appeared to have come out with the better deal, and within a few years they were selling nutmeg at a 60,000-percent markup. Speaking by video call from his home in Jakarta, Fadli emphasizes that for the Bandanese, “it was misery.”

The Dutch monopoly was broken in 1772 by a Frenchman who smuggled nutmeg seedlings to Mauritius and produced the first successful transplant. English incursions to the Bandas during the Napoleonic Wars also allowed them the chance to grab seedlings and transplant them to colonial centers in Penang, now part of Malaysia, and Sumatra, Indonesia, as well as in Sri Lanka, off the coast of India.

Today Indonesia is the largest nutmeg producer in the world, but it is grown largely on the islands of Java, North Sumatra and Sulawesi. Of the 44,000 or so metric tons that Indonesia produces annually, according to Bahalwan only 372 metric tons—less than 1 percent—is grown in the Bandas. And although Palau Rhun’s contribution to that is only 50 metric tons, he says, the terms of trade are better than at any time in 500 years.

After gaining independence from the Netherlands in 1949, the Indonesian government nationalized nutmeg plantations in the Bandas. In 1982 residents of Pulau Rhun took over the state-owned enterprise and divided the groves among the island’s families. Each now sells to a collective, which in turn sells to a range of global wholesalers.

“Everything is back in locals’ hands,” says Fadli.

Rhun may not have an internet connection, and its electricity may be spotty, but the nutmeg growers can once again trade as they themselves choose.

About the Author

Jeff Koehler

Jeff Koehler is an American writer and photographer based in Barcelona. His most recent book is Where the Wild Coffee Grows (Bloomsbury, 2017), an “Editor’s Choice” in The New York Times. His previous book, Darjeeling: A History of the World’s Greatest Tea (Bloomsbury, 2016), won the 2016 IACP award for literary food writing. His writing has appeared in the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, Saveur, Food & Wine and NPR.org. Follow him on Twitter @koehlercooks and Instagram @jeff_koehler.

Linda Dalal Sawaya

Linda Dalal Sawaya (www.lindasawaya.com; @lindasawayaART) is a Lebanese American artist, illustrator, ceramicist, writer, teacher, gardener and cook in Portland, Oregon. Her 1997 cover story, “Memories of a Lebanese Garden,” highlighted her illustrated cookbook tribute to her mother, Alice's Kitchen: Traditional Lebanese Cooking. She exhibits regularly throughout the US, and she is listed in the Encyclopedia of Arab American Artists.

You may also be interested in...

Polish Explorer's Manuscript on Arabia Helps Preserve Cultural Heritage

Arts

Nearly 200 years after his death, Polish adventurer and poet Waclaw Rzewuski’s manuscript documenting his experience in the Middle East has become important to advancing understanding of 19th-century Bedouin life and customs.

Moroccan Photographer Explores Oasis Culture at Sharjah Biennial

Arts

Moroccan photographer M’hammed Kilito explores richness of oasis culture at Sharjah Biennial

A Fasting Journey Through Ramadan

Arts

What’s it like as a non-Muslim to fast during Ramadan? Writer Scott Baldauf shares his journey through the holy month where he uncovers resilience, empathy and the powerful unity found in shared traditions.