Spice Migrations: Pepper

- Food

- Arts

6

Written by Jeff Koehler

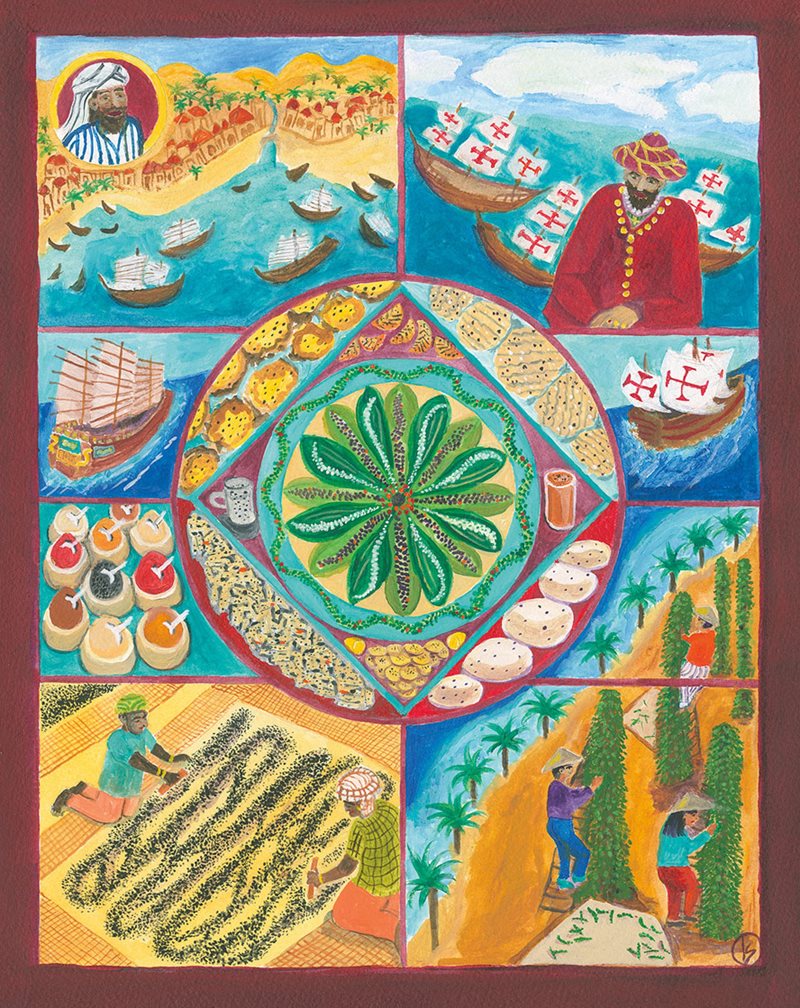

Art by Linda Dalal Sawaya

This is pepper country, the Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta declared of Malabar, India’s southwest coast along the Arabian Sea. Admiring the tropical forests and hills made bountiful by monsoon rains, there was “not a span of ground or more but is cultivated,” he observed. “Every man has his own separate orchard,” and these extend down the coast for the distance of “a two-month march” (about 400 kilometers).

Among the many ports in Malabar he visited in the 14th century, thee “flourishing and much-frequented” Kozhikode, known then as Qaliqut (and later Calicut), today in the state of Kerala. stood out. In its harbor, he wrote, “gather merchants from all quarters,” such as China, Java and Sri Lanka to the east and the Maldives, Yemen and Persia to the west.

Many of them traded in spices—especially cloves, nutmeg and cinnamon from further east and cardamom, ginger and cassia from Malabar itself. But one spice was king, anchor of the city’s success: Piper nigrum—black pepper.

Black pepper was then the most widely used spice in the world, and it still is, says spice writer and Times of India food critic Marryam H. Reshii. “You’d be hard pressed to find a single family around the globe whose kitchen or dining room dresser does not have black pepper,” she says. So commonplace is pepper that it frequently regarded as unassuming and humble. That’s deceiving. “Modest appearance notwithstanding,” she says, the spice that “has led world history for much of the last millennium is a giant.”

Piper nigrum is native to India’s Western Ghats mountain range. In the shady, steamy heat of its forests, and on Malabar’s coastal plain and neighboring hills, pepper thrives. Ibn Battuta described the pepper trees as looking a lot like grape vines. “They are planted alongside coco-palms and climb up them in the same way that vines climb,” bearing dozens of peppercorns on each single, slender spike.

As soon as one or two of the berries turn red, the whole spike is harvested, generally in autumn. Workers separate the berries between their hands or even their feet, and they spread them out in low piles on coconut mats or large patios. There they dry in the sun, and workers rake them from time to time until, as Ibn Battuta wrote, “they are thoroughly dried and become black.”

The process is essentially similar today, says Australian spice trader Ian Hemphill. “When fresh, green peppercorns are dried in the sun, a naturally occurring enzyme in the skin turns the berries black and creates a highly aromatic oil that gives black pepper its distinctive aroma and flavor,” he says. “The taste is warm, and the flavor full-bodied, round.” And hot, in a clean, sharp way, thanks to piperine, the active ingredient in the white heart of the peppercorn.

“Black pepper drying in the sun is one of the distinctive sights of Kerala’s countryside,” Reshii described in The Flavours of Spice. She recalled how as a child in Kochi, south of Kozhikode along the coast, she could see men “raking tons of pepper set out to dry on coconut-leaf mats.”

She adds that at any table in Kerala, there is no avoiding pepper: “It is the one state where the sting of black pepper will catch you at the breakfast table in your idli steamed rice cake, in the incendiary chutney served with your fragrant lamb biryani at lunch and during the tea-time snack of banana chips sprinkled with black pepper,” she says. And if you manage to avoid it during dinner, it’s a deep mystery. “Its fragrance and tingling heat will grab your attention even if there are just one or two peppercorns sprinkled over your food.”

Pepper is endowed with more talents than simple taste. “The oils in black pepper create an appetite stimulant,” says Hemphill, who is also author of the authoritative Spice & Herb Bible (Robert Rose, 2014). Pepper’s aromas make us salivate in anticipation, and as its pungency warms the tongue, it also chemically activates our gastric juices.

Long before Ibn Battuta, pepper was one of the earliest and most-important commodities sold to southern Asia and the lands around the Mediterranean. While the Romans were not first to use pepper in cooking, they were first to do so with regularity, according to Jack Turner, author of Spice: The History of a Temptation (Knopf, 2004). Among the 468 Roman recipes compiled in the first-century-CE collection Apicius, 349 call for pepper.

During the Middle Ages, pepper continued to travel west across the Arabian Sea and north through the Levant, often ending up in Constantinople. Some also went to Jiddah and overland to Makkah, Madinah and beyond, and more continued onward still to Cairo, Alexandria and the greater Mediterranean.

When the physician ‘Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi visited Egypt in the 13th century, he observed how Egyptians used black pepper, cinnamon and coriander in sweet chicken dishes. The 14th-century Egyptian cookbook Kanz al-fawa'id fi tanwi al-mawa'id, (Treasure Trove of Benefits and Variety at the Table) backs up his observation, asserting that filfil (pepper) “is added to all the main dishes and it is indeed the spice to use.”

But there were yet larger markets than these for pepper both domestically, within India itself, and around Asia, especially in China. In 1320, just 22 years before Ibn Battuta’s visit to Malabar, Marco Polo wrote: “I assure you that for one shipload of pepper that goes to Alexandria or elsewhere, destined for Christendom, there come a hundred such, aye and more too, to this haven of Zayton,” which is now called Quanzhou.

Even Ibn Battuta, arriving in Qaliqut, made passing note of 13 Chinese vessels at anchor. While Polo may have exaggerated, says Michael Krondl, author of The Taste of Conquest (Ballantine Books, 2007), in 1500 China consumed three-fourths of the global pepper supply. Thus, it is an irony of history, Krondl maintains, that the relatively smaller volumes of spices that went west ultimately had an outsize impact on world affairs. “That minority trade in Europe motivated a trade system that did in fact lead to globalization and colonization,” he says.

This began when Portuguese mariner Vasco da Gama reached India by sailing around Africa at the end of the 15th century. His exploratory visit was followed by a Portuguese fleet of 13 ships outfitted with cannons and crewed by more than 1,000 sailors who arrived in Qaliqut demanding exclusive access to the region’s resources—pepper chief among them. When they were rebuffed, says Manu Pillai, a Kerala-born historian and author, “the Portuguese took their business to Cochin [Kochi] instead—helping that port grow as the Arabs had helped Calicut—and began centuries of war” that broke both Indian and Arab control of trade for more than four centuries.

While pepper remains king of the world’s spice racks, India is today far from its largest grower. Pepper had spread long before Marco Polo, Ibn Battuta and Vasco da Gama saw it, and in their times Malabar produced about two-thirds of the world’s total. Siam (Thailand), Sumatra and Java (both now in Indonesia) grew substantial, competing amounts.

Today, Vietnam, Brazil and Indonesia produce more than 60 percent of the world’s pepper. And as pepper plants have proliferated, so too the aromas and various pungencies of the peppercorns have shifted depending on soil and climate conditions. For example, says Hemphill, “Vietnamese has a somewhat lemon-like profile, and to me, Indonesian is a little earthy and not as fragrant as Malabar.”

Experts generally agree that the south of India still produces the world’s most flavorful pepper. “I am often of the belief that the best spice is the one that comes from its country of origin,” Hemphill says. “As pepper is native to the south of India, and was traded from the Malabar Coast, I find Malabar Garbled number 1 [the highest grade of pepper] the most original.”

According to Reshii, this is perhaps to be expected: The hills of Malabar are drenched by the monsoon at exactly the moment the flower develops into the spice, she says, lending the region’s peppercorns their unique potency. Such conditions and traits cannot be duplicated, not even elsewhere in Kerala, she maintains. “I ask for Malabar Garbled Extra Bold,” she adds. “All I need to do is inhale the fragrance, and I can tell if it is what I am looking for.”

About the Author

Jeff Koehler

Jeff Koehler is an American writer and photographer based in Barcelona. His most recent book is Where the Wild Coffee Grows (Bloomsbury, 2017), an “Editor’s Choice” in The New York Times. His previous book, Darjeeling: A History of the World’s Greatest Tea (Bloomsbury, 2016), won the 2016 IACP award for literary food writing. His writing has appeared in the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, Saveur, Food & Wine and NPR.org. Follow him on Twitter @koehlercooks and Instagram @jeff_koehler.

Linda Dalal Sawaya

Linda Dalal Sawaya (www.lindasawaya.com; @lindasawayaART) is a Lebanese American artist, illustrator, ceramicist, writer, teacher, gardener and cook in Portland, Oregon. Her 1997 cover story, “Memories of a Lebanese Garden,” highlighted her illustrated cookbook tribute to her mother, Alice's Kitchen: Traditional Lebanese Cooking. She exhibits regularly throughout the US, and she is listed in the Encyclopedia of Arab American Artists.

You may also be interested in...

The Bengalis are famous for their “chops,” or potato croquets eaten as snacks with tea.

Food

The Bengalis are famous for their “chops,” or potato croquets eaten as snacks with tea.

Silk Roads Exhibition Invites Viewers on Journeys of People, Objects and Ideas

Arts

An evocative soundscape envelops visitors as they enter the Silk Roads exhibition at the British Museum in London. Huge screens along one wall project images of landscapes and oceans, while visitors are invited to experience the scents of balsam, musk and incense contained in boxes around the exhibition.

The Heart-Moving Sound of Zanzibar

Arts

Like Zanzibar itself, the ensemble style of music known as taarab brings together a blend of African, Arabic, Indian and European elements. Yet it stands on its own as a distinctive art form—for over a century, it has served as the island’s signature sound.