In a remote reach of the Sahara, near Egypt’s western border with Libya, it takes a scramble across dunes, scree and a cliff to reach the cave of Foggini-Mestikawi.

More an alcove in a rock wall, it is adorned with the 8,000-year-old rock art of the people and the animals they lived with and preyed upon: giraffes, ostriches, antelopes and gazelles, curiously headless lions, and handprints and depictions of the humans who painted them.

That was before the climate warmed and dried. The people moved east, to where the water was: the Nile Valley. Some 5,000 years ago, King Menes united the peoples of Upper and Lower Egypt, and the rest is quite literally history—which is also natural history.

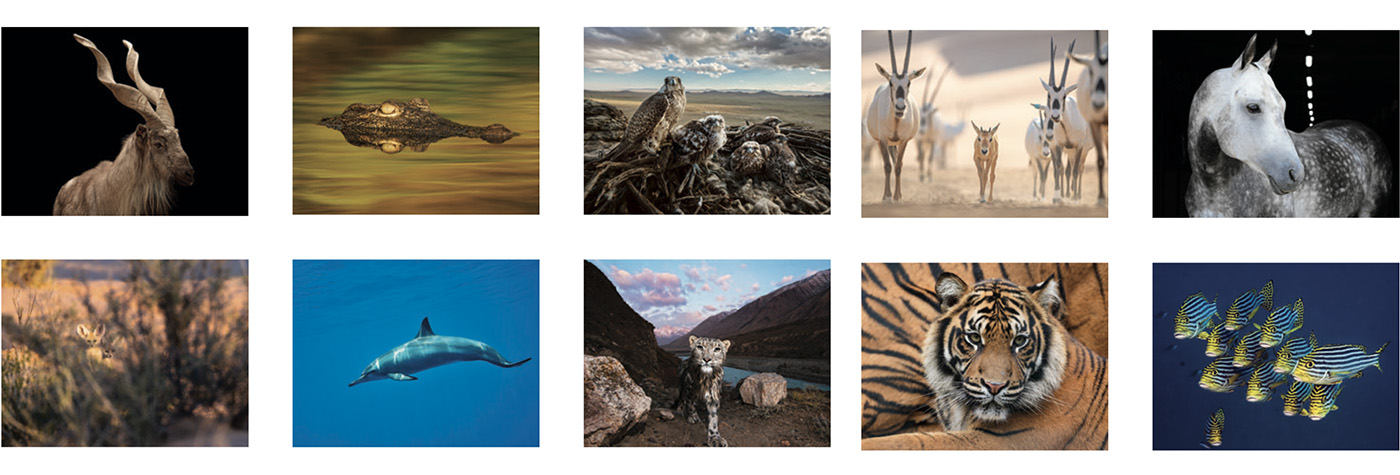

People in pharaonic Egypt continued to depict their animals, wild and domestic, with unprecedented accuracy. Animals were farmed, and they were also deified. There was Thoth, represented by the Sacred Ibis and the Sacred Baboon—both species now extinct in modern Egypt. There was Sobek, the crocodile god of fertility and the Nile, and there was Horus, the falcon-headed god: In the temple of Kom Ombo, in Upper Egypt, the two were, uniquely, celebrated together.

Today the Nile crocodile is limited to the human-made confines of Lake Nasser. But in the air, still widely resident are the raptors: the Kestrel, the Lanner, Sooty and Barbary falcons. There is also the Saker, renowned for its size and hunting prowess, that has been so extensively captured that it is now endangered. Dozens of species of other birds pass through: Each spring and fall, the greater Middle East plays host to birds by the millions as they make their way back and forth from breeding lands across Europe and Asia and wintering grounds in Africa.

It is not just birds that migrate. The waters of the Red Sea support some of the richest marine environments on the planet. The coral reefs equate, in terms of biodiversity, to tropical rainforests, and sea turtles, including loggerhead and green turtles, breed in the region. At the Ra’s al-Jinz Reserve in easternmost Oman, female green turtles haul themselves ashore at night to lay their eggs after years at sea. It is a moving experience to witness: No flash photography or mobiles are allowed, but in 2015, with my own pencil and paper, I was permitted to sketch with rapt impunity.

Like the Sahara, much of the Arabian Peninsula above the water might seem an austere, even lifeless, biome. But there are myriad species there, many of whose names stem from Arabic—jirds, gerbils, jerboas and more. Among the rare larger denizens, perhaps the rarest is the Arabian oryx, a species recently brought back from the brink of extinction.

The Arabian oryx may have been one of the origins of the legendary unicorn.

Half a century ago, this antelope of only the most extreme of deserts was reduced to a handful of individuals. Since 1972 it has been gradually reintroduced in protected areas such as Jiddat al-Harasis in Oman, Al Reem Biosphere Reserve in Qatar and several reserves in Saudi Arabia. Though large and white with dark, nearly straight horns, it is so elusive in the shimmering desert that the oryx, with its long, slender horns, may have been one of the origins of the legend of the unicorn.

Whether on land, in the sea or in the air, where there are fauna, there are predators, often in addition to human hunters. Where there are oryx, there are jackals; where there are markhors there are snow leopards, and where there are tigers there are sambars and sikas. There were cheetahs too, once widespread in the Middle East but now reduced to only a few in the wild, in Iran. But cats were worshipped in pharaonic Egypt as the lioness Sekhmet and also as the cat goddess Bastet. In Sumeria the King Gilgamesh was portrayed embracing the lion. On the Arabian Peninsula today, the leopard endures, clinging to the remote reaches of the southern mountains.

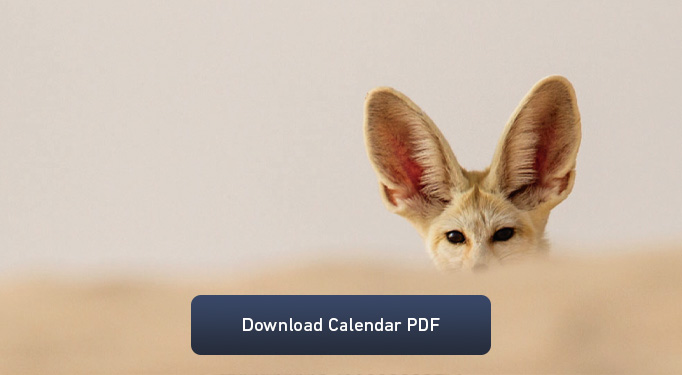

Perhaps the best-adapted of desert predators are the foxes. Within Arabia there are there are Blanford’s foxes, red foxes and Rüppell’s sand foxes, but from Morocco to the Sinai Peninsula, the “poster species” is the fennec fox, which appears on the cover of this calendar. You would be lucky to see one, but after a night out under the desert skies, on the sandy ground crisscrossed by the tracks of numerous nocturnal visitors, perhaps among them you would find those of the fennec.

Today, everywhere, our natural environments are threatened by climate change, habitat loss and the human footprint. Many fauna painted in the Foggini-Mestikawi cave have disappeared. Yet rejuvenations of species and increases in habitat protections by conservation-minded organizations continue to offer hope. The managed population of the Arabian oryx, the protection of the green turtles, and the recent reintroduction of the cheetah into Kuno National Park, India, are examples worth following. The November 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, gives opportunities for global attention to invigorating environmental resurgences.

About the Author

Paul Lunde

The late Paul Lunde authored more than 60 articles for AramcoWorld. He was a senior research associate with the Civilizations in Contact Project at Cambridge University and also co-author, with Caroline Stone, of Ibn Fadlan and the Land of Darkness: Arab Travellers in the Far North (Penguin, 2012).Richard Hoath

Richard Hoath is the author and illustrator of A Field Guide to the Mammals of Egypt and writer of the recently published The Birds of Egypt and the Middle East. He is a leading naturalist, ornithologist and long-time resident of Egypt who has traveled throughout the Middle East in search of varied, wonderful, and elusive wildlife. He is on the faculty of The American University in Cairo.

You may also be interested in...

Drones, Mangroves and Carbon Superpowers

Science & Nature

Mangroves have been drawing increasing global attention for a quiet superpower: the ability to store up to five times more carbon than tropical forests. While coastal development, uncontrolled aquaculture, sea-level rise and warming temperatures have all contributed to the 35 percent decline in mangrove forests worldwide since the 1970s, government agencies, scientists and local communities are increasingly rallying to protect and replant mangroves. One group is taking restoration to notably new heights.

Sustainability’s Dubai Beta Lab

Science & Nature

Expo 2020 Dubai closed in March after showcasing buildings and displays designed to maximize sustainability, one of the Expo’s top themes. Creative systems for power generation, water conservation and city planning all addressed global challenges.

FirstLook: A Mother’s Kiss

Arts

Science & Nature

For more than eight hours, we navigated the Sekonyer River in a wooden boat, cruising through Tanjung Puting National Park in the Central Kalimantan region of Borneo, Indonesia.