Key to a Kingdom: Ronda’s Secret Water Mine

- History

- Arts

16

Written by Ana M. Carreño Leyva

Photographed by Richard Doughty

“One of the most invincible … a fortress that melts with the clouds, belted by freshwater rivers and springs.”

—Abu al-Fida, early 14th c. CE

Approaching the region of the Serranía de Ronda, just inland from the Mediterranean’s Costa del Sol, one passes through mountains and rugged surroundings that have challenged settlers, merchants, travelers and invaders for thousands of years. Over the last ridges, a broad valley opens, circled around by hills and hazy massifs.

Near its center, set like a jewel in this natural crown, a small tableland rises some 200 sheer meters above the fields: Ronda, spectacularly cleft by its famous Tajo, a narrow, nearly vertical gorge cut over five million years ago by the river Guadalevín, a name that comes from the Arabic wadi al-laban (valley of milk), after the prosperity its waters brought to the grazing lands below.

The city appears precarious, perched along the rocky crests of the ravine and surrounding cliffs. Picturesque today, for centuries this setting made Ronda one of the most strategic natural strongholds in a frequently contested, borderland area.

While its spectacle gives the town “a legendary character that still persists,” says Virgilio Martínez Enamorado, professor of medieval history at the Universidad de Málaga and a specialist in al-Andalus, or Muslim Spain, this is a region that has been settled since even before Neolithic times. Iberians, Phoenicians Celts, Romans, Visigoths, Arabs and Berbers have all predominated at different times, each making here a center stage thanks to Ronda’s defensive qualities.

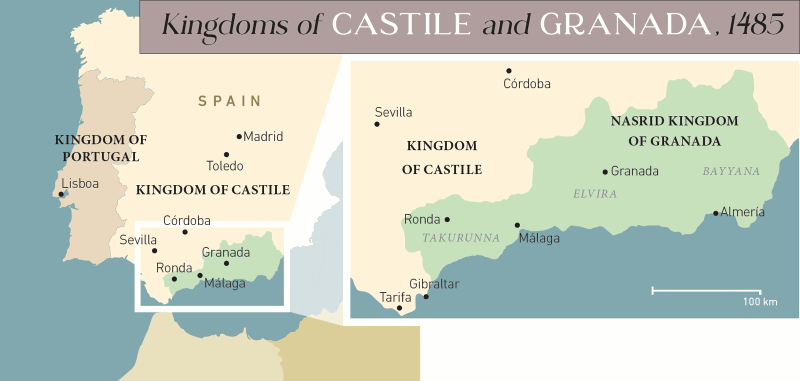

“Its urban history goes back to antiquity, to Neolithic times, in nearby Acinipo, where Romans settled later, as recorded by Pliny and Ptolemy,” says Martínez Enamorado. By the 11th century CE, the Banu Ifran, a Berber tribe, made Ronda capital of the district they called Takurunna. That name, he explains, embodied the cultural layers that characterized the region: It compounded the Berber article ta- with an Arabicized pronunciation of the Latin word for crown, corōna. Also in the 11th century CE, Ronda became capital of a taifa, or independent kingdom; by the 14th century, Ronda had joined the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada and became its westernmost realm.

Iberians, Phoenicians, Celts, Romans, Visigoths, Arabs and Berbers have all predominated at different times in Ronda.

Around that time, Kurdish historian and geographer Abu al-Fida wrote about the town in his Tarikh al-mukhtasar fi akhbar al-bashar (Concise History of Humanity): “As for the district of Ronda, it is one of the most invincible ma’qal [shelters] in al-Andalus. It is a fortress that melts with the clouds, belted by freshwater rivers.”

A century before him, in the mid-1220s CE, Yaqut al-Hamawi, born in Constantinople, wrote Kitab mu‘am al-buldan (Dictionary of Countries), which drew upon earlier works by Ptolemy and Mohammed al-Idrisi. He noted that “Takurunna in al-Andalus is located in a very mountainous area and has countless inaccessible wells and castles.”

Around this same time, Takurunna native son al-Himyari called his home region “a very old city, with a great number of vestiges”—and his words closely echoed ones written in the earliest-known Arab-based account of al-Andalus, the 10th-century Crónica del moro Rasis (Chronicle of the Moor al-Razi).

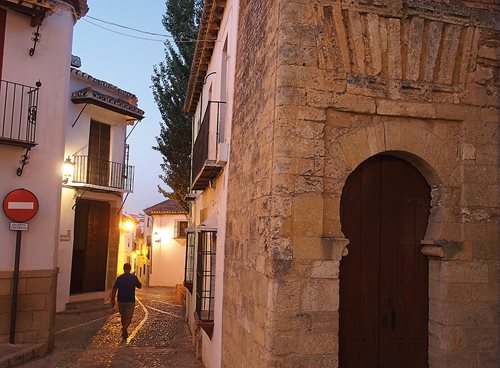

For the town today, this history is much overshadowed by the marketable pleasures of Ronda’s rugged beauty and small-town appeal. Spanned by stone bridges, the drama of the Tajo and the surrounding cliffs make Ronda one of southern Spain’s leading tourist destinations. It has been this way since the 18th and 19th centuries, says Ronda Municipal Delegate for Culture Alicia López Dominguez. It was in this era that it became a favorite on the itineraries of so-called “Romantic travelers,” generally writers and artists from Europe and the Americas seeking inspiration from both natural beauty and the exoticism of remnants of Hispano-Muslim culture.

While today most visitors come for the “astonishing landscape and exceptional gastronomy,” she says, they often find also “a surprising history with a monument unique not only in Ronda but nationally, la mina de agua,” the water mine carved in the 12th century CE from the Tajo’s edge down through 60 meters of rock to a spring-fed well and the river.

Historic Arabic sources refer repeatedly, if briefly, to Ronda’s strategic defensive role, but about the water mine, Martínez Enamorado says, “there are no concrete references. It’s a place that hardly appears in the Arab chronicles,” and only briefly in later Christian ones, too. Systematic archeology, by a team from the Universidad de Sevilla, began only recently.

“Hardly anything has been studied so far,” he says. As a result, “a halo of legends” has long since filled the gaps, most notoriously the story that the water mine had been a hiding place for treasure stashed away by Ronda’s King Abd al-Malik, who ruled from 1333 and 1339.

While no treasure of gold or gems has ever been found, the mine’s real treasure was always the water. Under attack, the only way for the inhabitants of the tableland town to get water for drinking or cooking was through the mine. “This was very hard work,” says Martínez Enamorado, because the water had to be carried up the mine’s stone stairs in one goatskin sack after another. This made the mine itself a kind of treasure, one that worked the other way around too: In 1485 the water mine was the decisive prize for the army of Rodrigo Ponce de León, Marquis of Cádiz, who led the army of the Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella into Takurunna in early spring of that year.

The water mine is a qawraja, a fortification built to protect a resource—often a well. Of hundreds across al-Andalus, it is the most elaborate one known.

Many doubted his forces could take over Ronda, so well was it garrisoned by its own army as well as its topography, walls and towers.

According to Castilian royal secretary and chronicler Andrés Bernáldez, the Christian forces deployed 20,000 infantry, 1,500 cavalry and 1,100 artillery carts that used gunpowder to fire cuartadao, the forerunner of the mortar. They surrounded Ronda, laid siege in late April, and on May 22 took possession of the city.

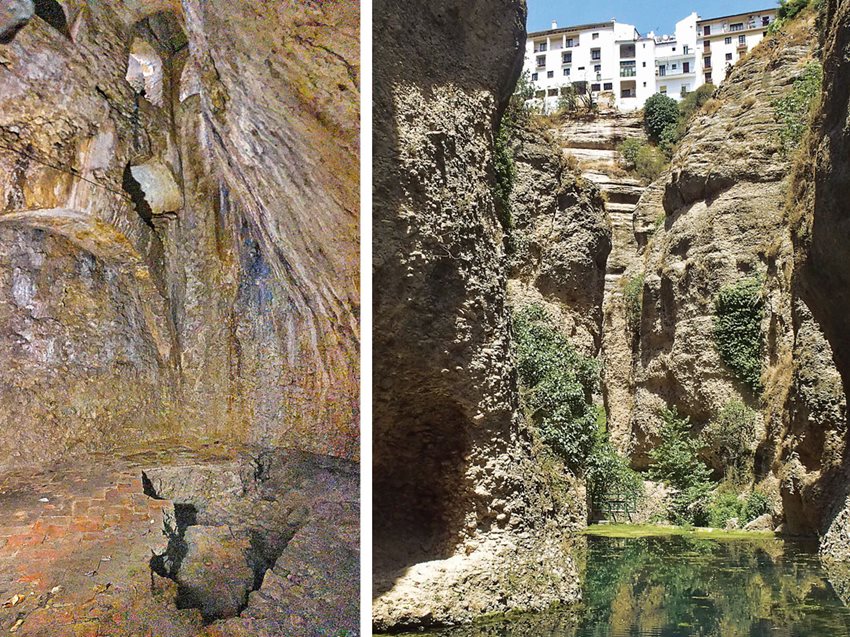

It has been open to the public only since the 1990s. The natural lighting from the windows has been supplemented with discreet electric bulbs, and tourists—unlike the slaves, servants and soldiers who bore water in goatskins—can steady their footing on each irregular step thanks to modern metal handrails.

With its organically winding, labyrinthine structure, the descending passageway looks phantasmagorical, a surreal staircase where light is filtered as slowly as the water that seeps down the walls and drips from the ceilings in this engineered, vertical cave. It has several bench-like resting niches along the way, some covered by arches and vaults, others pierced by windows, and recesses in the walls whose purposes, Martínez Enamorado says, remain uncertain—only one of the several enduring mysteries of the water mine. (See sidebar, above.)

Post-Reconquista Spanish accounts say the mine was constructed and manned by captive Christians who, in addition to hewing rock and carrying goatskins, would have also turned by hand the crankshaft of the noria, or waterwheel, at the heart of the mine, about three-fourths of the way down to the river.

At some 10 meters from floor to ceiling, the noria’s chamber is the tallest of the mine’s three excavated “saloons,” as Carter referred to them. The noria would have been attached to an axle mounted in the wall, Martínez Enamorado explains. It would have used a belt or ropes that dropped through the floor to the level of the spring close to the river level. Buckets attached to it would raise the water to a cistern from which skins could be filled, clamped or tied and then hauled up the stairs. Human traction was the only way to draw, load and carry the water, Martínez Enamorado says, since no draft animal could negotiate the stairway. The space shows a floor of brick, arranged in a herringbone pattern, that began to be uncovered in 2019 during the first of the four phases of excavations planned by the Universidad de Sevilla, each focused on a different part of the mine.

Almost at the same level, along the outside wall, a room with several vaults and a lower ceiling was made with windows wide enough to invite speculation that this may have been an armory for weapons, ammunition, or perhaps even at times a small prison.

Down another a few more meters is one of the most surprising places in the mine, popularly known as “The Hall of Secrets.” Actually a small, square room, its ceiling is a finely constructed qubba, or a hemispheric dome; in one wall is an archer’s slit of a window. Considering the traditional use of this type of domed constructions that resolve the corners of a square plan, the room suggests that the mine may have had other, as-yet-unknown uses, says Martínez Enamorado. “The qubba sacralizes the space, or at the very least, it implies that it was a multifunctional space,” he says. The Spanish accounts say it was here that in 1485 the Marquis of Cádiz posted his soldiers.

The room owes its popular name to the singularity of its acoustics, which allow a whisper from side to be heard across the room but not in the middle. Of course, this has helped amplify also the whispers of legend, such as stories of the room being a spa for Moorish ladies of the court, despite it not looking at all comfortable for this. Yet this also suggests why, down at the river’s edge, in the open air, the entrance to the mine appears not camouflaged but rather flaunted with a wide, rectangular door bordered with a stone frieze whose decoration seems out of place for military purposes. Today a metal deck offers visitors a view of the grottos of the river and the tapered stone of the Tajo that rises like buttresses, as if designed to keep the town from tumbling off the edge.

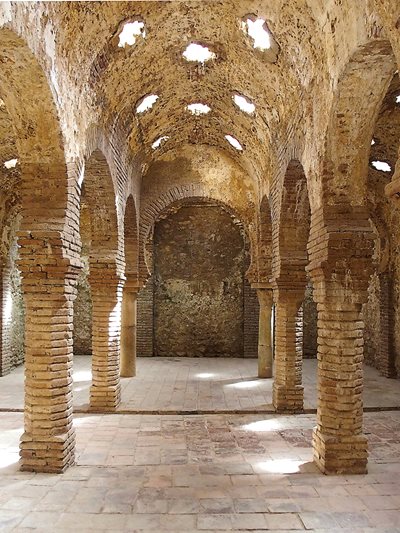

The growth of the city that followed the Catholic conquest took place mainly on the side of the Tajo opposite the old Arab city that today preserves its character amid steep, winding streets and scattered reminders of its centuries as capital of Takurunna. There is a single, modest, square, stone minaret and the best-preserved Arab bathhouse in all of Spain. A tall horseshoe arch, covered in elaborate Arabic calligraphy, carved in bas relief during the city's Nasrid era, lies tucked within the church of Santa María la Mayor: The arch originally framed the mihrab, or prayer niche, of the mosque Arabs built over a Roman temple. And on every side of Ronda, walls and turret-towers remind us that the citadel town was a ruler’s key to a rich and rugged region.

To those Berber and Arab people who first crossed the Serranía from the drier lands of the Mediterranean’s African shore “with the light sound of water, plotting the desert’s memories,” as wrote Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges, there would be no key to Ronda, no treasure of their Takurunna, greater than the water for which they would hew the rock in secret to ensure its blessings.

About the Author

Ana M. Carreño Leyva

Ana M. Carreño Leyva lives in Granada, Spain, where she is a translator of modern languages and a freelance writer who specializes in the diverse cultural heritages of al-Andalus and the Mediterranean region.

Richard Doughty

Richard Doughty is editor of AramcoWorld. He holds a master’s degree in photojournalism from the University of Missouri.

You may also be interested in...

Celebrating 75 Years of Connection Stories and Culture

Arts

History

Since its origins in 1949 as a company newsletter for Aramco, AramcoWorld has evolved to focus on global cultural bridge-building across the Arab and Muslim world and beyond.

Polish Explorer's Manuscript on Arabia Helps Preserve Cultural Heritage

Arts

Nearly 200 years after his death, Polish adventurer and poet Waclaw Rzewuski’s manuscript documenting his experience in the Middle East has become important to advancing understanding of 19th-century Bedouin life and customs.

Sara Domingos Investigates the Threads of Portugal’s Multilayered Heritage

Arts

In a cavernous studio beneath the Church of Saint Mary Magdalene, just a 15-minute walk from Lisbon’s Moorish Quarter, a cross-cultural interplay between the Portuguese city’s old Islamic and modern-day traditions manifests under the steady hands of Sara Domingos.