While Samira Jabeur practiced drills at the Tennis Club of Monastir in Tunisia, her then-3-year-old daughter, Ons, would toddle around nearby courts, watching, playing and picking up rogue balls as they settled along the green clay. She recalls herself as a kid who “loved anything to do with a ball.” Long before Ons Jabeur became the first Arab—male or female—to be ranked among the top 10 professional tennis players in the world, she was just an ordinary girl with a racket.

“I owe a lot of my success to my mother,” says Jabeur, 27, currently ranked No. 11 in the world by the Women’s Tennis Association. “She always wanted to play, and that was what got me started.”

Though Tunisia is just across the Mediterranean and east from France and Spain, countries known for tennis champions as well as prestigious tournaments, tennis in 1990s Tunisia, when Jabeur was a girl, wasn’t popular. What few courts existed were mostly in touristic cities such as Tunis, Hammamet and Jabeur’s hometown of Sousse. To play tennis required effort, means and dedication, and even today the game remains a niche sport compared to soccer, volleyball and even the newly popular handball.

By age 12 Jabeur was making a 150-kilometer trek north from Sousse to Tunis, the nation’s capital, where she trained with top coaches at the country’s leading athletic training center, Lycée Sportif El’Menzah. She also trained in France, which has consistently produced some of the world’s highest-ranking tennis professionals.

“I always dreamed I could be one of the best players in the world,” says Jabeur, whose first name means “removal of fear” and “to provide a comforting presence for another” in Arabic.

By 16 Jabeur had won numerous tournaments, and in 2010 she finished second in the Junior Grand Slam singles final at the French Open in Paris. She returned to the Roland Garros Stadium the following year and became the first Arab to win a Junior Grand Slam singles title since Egypt’s Ismail El Shafei won the Wimbledon boys’ crown in 1964.

“I always dreamed I could be one of the best players in the world.”

—Ons Jabeur

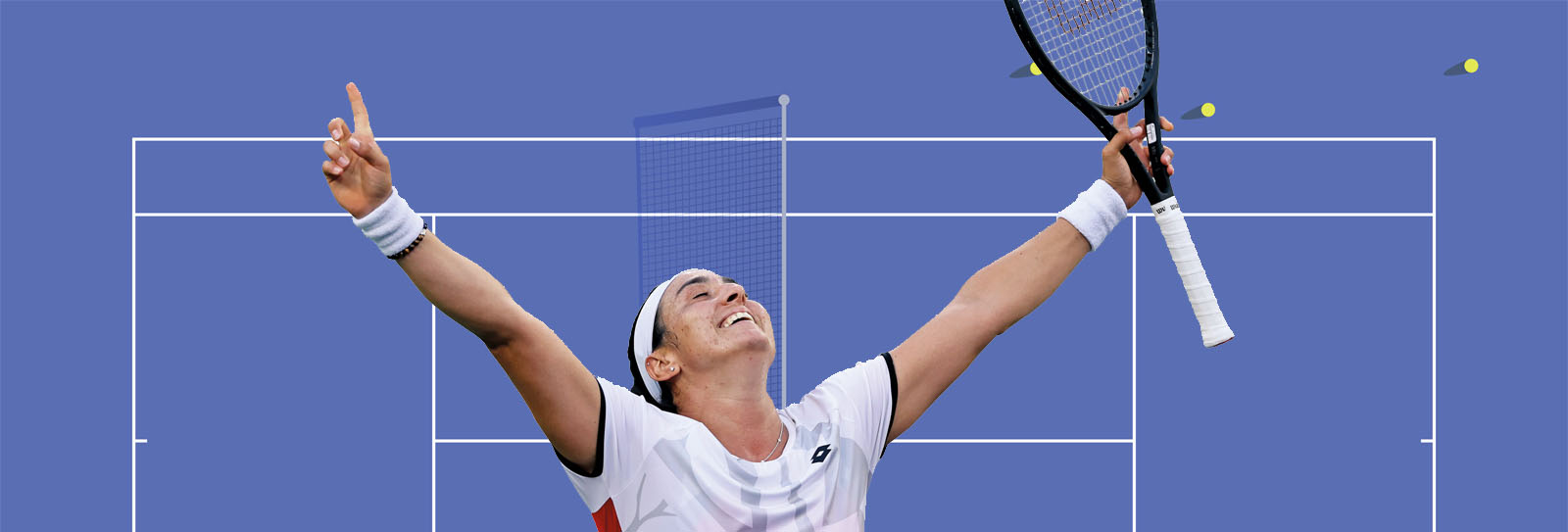

But it was last year in June, after defeating Daria Kasatkina of Russia at the Birmingham Classic in Birmingham, England, that Jabeur made history as the first Arab woman to win a major Women’s Tennis Association title.

“That victory in Birmingham felt so good because it was a long time coming,” says Jabeur, who puts in five or more hours on the court every day when not competing. “I know some people expected me to achieve a WTA title earlier, but injuries held me back.”

Her coach, fellow Tunisian and former pro Issam Jallali, succinctly assessed Jabeur and her long-awaited WTA title.

“She is very gifted and she works hard,” says Jallali, 41.

Jabeur’s Russian Tunisian husband, Karim Kamoun, a former fencer, also coaches her off the court, serving as her personal trainer.

“It’s nice to have him around,” explains Jabeur, who says the couple hopes to start a family once she retires. That may not be far away, she says, as most tennis pros compete until they reach about 33.

“Honestly, I don’t know how long I’ll be able to play at this level, because it all depends on how your body deals with injuries and how your mind handles motivations,” she says. “But if I’m playing well at 34, I’ll be staying on the tour.”

Countries comprising the Middle East and North Africa account for more than 420 million people, yet they have only produced five top-100 tennis players, including Jabeur, in the sport’s history. The only other Arab woman to reach a similar level was also a Tunisian: Selima Sfar, who ranked 75th in the early 2000s. To date, Jabeur’s highest ranking has been No. 7, and as of the publishing of this article, she stands at No. 11.

“I tell young women, and boys too, that if they train and work hard to be a success, they may achieve their goals,” she says. “And not in just tennis, but in any other sport or activity where you want to prove yourself.”

Even though Jabeur has competed and trained all over the world, she has always been most comfortable in Tunisia, where she calls herself and her achievements a “100 percent Tunisian product.” She wants to use her celebrity to encourage young athletes to excel at life, whatever path they take.

“I especially hope Tunisian and Arab girls can be inspired by my story and my success. I am also getting inspired by them,” she says. “I hope I can have a positive influence for more and more generations. That would be the best thing I can do.”

While ascending in popularity over the past few years, Jabeur has become a fan favorite too for what she describes as her “crazy” drop shots and slices that can leave opponents baffled and off balance. Her fans have been known to enthusiastically wave red-and-white Tunisian flags before and after her matches and to sing chants that are usually reserved for Arab and Africa Cup soccer matches. Supporters have come together through multiple fan pages on Facebook, and Jabeur’s own professional page on Facebook has nearly 1 million followers.

Longtime fan and Tunisia native Hayfa Chine has been following Jabeur’s success for the last eight years. A tennis player herself, Chine has enjoyed watching Jabeur’s rise and has traveled to Montreal, New York and Chicago to watch Jabeur compete.

“I am very proud of her,” says Chine, who now resides in Ottawa, Canada. “She’s a real inspiration to me and others.”

Chine says she loves watching Jabeur’s footwork on the court.

“I really appreciate the way she moves, the way she plays and especially her drop shots. She is very smart, and she has amazing energy. Sometimes her shots are magical,” Chine says.

Chine, who has posed with Jabeur while holding a Tunisian flag at last year’s Chicago Fall Tennis Classic, says each time she’s conversed with her favorite athlete, she finds Jabeur engaging and humble.

“She also has a wonderful personality, and while she is quite focused in her matches, she’s friendly and kind off the court,” Chine says.

“I especially hope Tunisian and Arab girls can be inspired by my story and my success.”

—Ons Jabeur

In 2021 Jabeur was playing some of the best tennis of her career against top pros, including Spain’s Paula Badosa and Garbiñe Muguruza—both ranked in the Top 10—and US fan favorite Venus Williams, whom Jabeur defeated last summer at Wimbledon.

“I am learning every day and working hard every day, too. I want to stay positive and be more successful in all that I do,” she says.

With Jallali by her side, Jabeur has racked up 11 titles on the International Tennis Federation (ITF) circuit, a steppingstone to the WTA, and, as well as being the first Arab to reach the top 10, has garnered other firsts for the Arab world—including first Arab to reach a Grand Slam quarterfinal at the 2020 Australian Open and first Arab to break into the top 50 in the history of WTA rankings.

After winning Birmingham again last year, Jabeur received praise from childhood idols Andy Roddick and Kim Clijsters. She also heard from US tennis icon Billie Jean King, who won 39 Grand Slam titles, including six Wimbledon singles crowns. In an October interview with Dubai-based The National, King said she wouldn’t be surprised if Jabeur becomes No. 1. “I think she’s got the ability to go much higher,” King said.

Serena Williams, formerly ranked No. 1 and sister of Venus Williams, commended Jabeur at a Wimbledon press event for “breaking down barriers” and “inspiring so many people, including me. She gives 100 percent every time.”

Over the next few years, as Jabeur continues to compete, she hopes to continue increasing her professional ranking in pursuit of her dream of reaching No. 1. But once retired, she plans a quiet life in Tunisia, where she can work with youth, mentor young women and open a tennis academy in-country where she can nurture a culture of tennis excellence in North Africa and train future tennis champions—so she’s not the only one.

“That would be a good life,” she muses. “That is my ultimate goal.”

You may also be interested in...

A Life of Words: A Conversation With Zahran Alqasmi

Arts

For as long as poet and novelist Zahran Alqasmi can remember, his life in Mas, an Omani village about 170 kilometers south of the capital of Muscat, in the northern wilayat (province) of Dima Wattayeen, books permeated every part of his world. “I was raised in a family passionate about prose literature and poetry,” Alqasmi recalls.

Celebrating 75 Years of Connection Stories and Culture

Arts

History

Since its origins in 1949 as a company newsletter for Aramco, AramcoWorld has evolved to focus on global cultural bridge-building across the Arab and Muslim world and beyond.

A Fasting Journey Through Ramadan

Arts

What’s it like as a non-Muslim to fast during Ramadan? Writer Scott Baldauf shares his journey through the holy month where he uncovers resilience, empathy and the powerful unity found in shared traditions.