The Long Wandering of the Damascus Rose

- Arts

15

Written by Tristan Rutherford

Photographed by Rebecca Marshall

Delka Kirova has lived a life in roses. Grandmother, community organizer and lifelong rose picker, she works from a modest office alongside a centuries-old library in the Bulgarian village of Rozovo. The scent is almost overpowering but each rosy object in Kirova’s office has its purpose. On her office table sits a jug of roses, which Kirova uses to demonstrate how to pick rose buds. On her desk are vials of rosewater, which she once used to massage her children to protect their skin against eczema and mosquito bites. On her sagging shelves are books of rose poetry, from which she treats her guests to a reading. “Roses are everywhere,” Kirova explains. “This flower is everything for us.”

Kirova may be a grandmother with a slow gait, but her delicate face is as vibrant as a bloom. Perhaps that is because, like almost all of Rozovo’s 1,000 residents, she started picking roses young.

The prickly process began at 5 a.m., but her 1970s memories are redolent of fragrance and friendship. “The morning was so clean, the petals were laced in dew, the birds made a song. From our home we took tomatoes, cheese, coffee and bread.” Kirova and her young colleagues worked hard to “pluck the pink petals on the first day a bud begins to open,” before their life-giving oils, which can regenerate cells and act as an antiseptic, dissipated in the mid-morning heat.

Kirova’s memories blossomed in Bulgaria’s 100-kilometer-long Valley of Roses, one of the best places on earth to grow roses. Bulgaria is nestled in southern Europe, ringed by Romania, Serbia, North Macedonia, Turkey and Greece. Four centuries ago, roses brought wealth and health, before the rise and fall of communism dented the blooming industry. Today a rose resurgence is under way despite changing demographics and climate concerns. And right outside Kirova’s small office a rejuvenated park has been planted with fresh rose shrubs, turning a morning stroll into an olfactory sensation.

The story of how Kirova’s “pink petals” arrived outside her office in Rozovo, via Samarkand, Rome and Syria, is even more flowery. The petals belong to the Damascus rose, a two-meter-tall hybrid with the botanical name Rosa x damascena, that was born by chance on the Turkmenistan-Uzbekistan-Afghanistan border an estimated 7,000 years ago. Following the last Ice Age, Rosa gallica—one of Rosa x damascena’s three parent species—was blown east to Central Asia. Rosa fedschenkoana—an even rarer species—migrated north over the Himalayas as the climate warmed. Here Rosa gallica and Rosa fedschenkoana met a wild Himalayan rose, Rosa moschata, and together they produced a hybrid—indicated today by the “x” in its scientific name—that produced a uniquely fragrant perfume.

Robert Mattock, who holds a doctorate in biological sciences and is a world authority on the hybrid’s botanical and horticultural history, has traced the origin and passage of Rosa x damascena across the world. He started on the Silk Road, checking Uzbek carpets and very old Central Asian manuscripts.

“We found records of distillation in a crude form of petals that went back to about 4000 BCE on the Afghanistan-Uzbekistan border,” Mattock explains. Stone presses used for making rosewater from petals were found near Samarkand dating from 4,500 years ago. Around 4,000 years ago, the cuneiform tablets, written in the East Semitic language of Akkadian, became more specific.

Mattock also explains that from Kazanlak to anywhere Rosa x damascena grows, generations of women have known that rosewater can ease menstrual cramps and reduce inflammations—conclusions recently backed up by research. Midwives have long administered rosewater as a muscle relaxant for childbirth, and it is marketed today as a skin softener. “Of course, these women talked to their sisters,” says Mattock, “and it passed down the line, from Samarkand to Rome.”

In pre-Christian Rome, rosewater was also served in sweets, and roses featured in frescoes and even had a festival, Rosalia, held in its honor. From the 10th century CE, Syrian growers began to cultivate the flower in greater quantities. The 12th-century-CE geographer Ibn Khaldun noted that one province of Syria “was required to give a tribute of 30,000 bottles of rosewater annually to the caliph of Baghdad.” The European Crusades had one fragrant silver lining: Christian combatants carried the rose back with them to Europe—with its “Damascus” prefix.

Through war and peace, love and recipes, the Damascus rose has undertaken one of botanical history’s greatest migrations. That is partly because of its fabulous fragrance and life-affirming properties, and partly because it is incredibly tough. Mattock, who runs Mattock Rose Science, a rose research subsidiary of the company Saint Fiacre Ltd, explains: “If you keep a rose sucker damp, wrapped in hessian sacking, it can survive harsh arid climates and rough terrain.” Evidence suggests that one form of the Damascus rose was able to transmigrate from Central Asia to Morocco via Egypt, Libya and across the northern Maghrib.

Kirova lives at the heart of the Damascus rose’s latest cultural home. A few kilometers north of her village of Rozovo sits Kazanlak, the capital of the Valley of Roses. With 45,000 residents, the town is blooming. Local businesses include the Hotel Roza, Rosa opticians and Rozova Dolina Kazanlak, the town’s soccer team. Residents look like they have just stepped out of a facial salon—or a moisturizer commercial—with skins as radiant as blossoms. Flowering roses fire off so much scent that they stop travelers in their tracks. German General Helmuth von Moltke, not a man known for frivolity, visited Kazanlak in 1837 and noted: “The air is full of fragrance. Kazanlak is the Kashmir of Europe.”

In a flower-filled park sits a new museum dedicated to the history of roses. The Kazanlak Rose Museum documents the Damascus rose’s journey from Syria, across the Ottoman Empire, to Bulgaria in the 17th century.

A museum exhibit shows the alchemy of distilling rosewater into rose oil. This gives the product greater longevity and aromatic intensity yet a smaller volume, rendering it perfect for transportation. The process involves an alambik (from the Arabic inbiq), which is a copper cauldron topped with a snout, through which steam gets pushed through armfuls of rose petals. The scented steam then condenses and drips into a rosewater vat. The museum’s alambik might be recognizable by Ibn Sina, the father of modern medicine from Bukhara in Central Asia, who produced the first distillation of essential rose oil, also known as attar, in the 10th century CE by using the exact same method.

Another museum display shows konkumi (singular konkuma), round, flask-like iron vessels used to export rose oil. The biggest one was last used in 1947, yet it still exudes a glorious perfume. Even using the latest technology, it still takes 3,000 kilograms of Damascus rose petals to make 1 kilogram of rose oil. There are also tiny decorative containers, known as muscals, that each hold 5 grams of oil—a quantity that is priced today at about US$50.

It still takes 3,000 kilograms of rose petals to distill a single kilogram of rose oil.

“A lot of the terms in rose production, like konkuma and muscal, have Middle Eastern origins,” says Kazanlak Rose Museum Director Momchil Marinov, whose passion for roses led him to study the economic history of the Valley of Roses. The origin of the town’s name, Kazanlak, comes from an Ottoman Turkish word that means “field of cauldrons.”

In particular, the valley’s Muslim population used roses in their cuisine, explains Marinov. “The rosewater was also used in local Islamic customs and funerals,” and still is, in a nation that has an estimated 10 percent Muslim minority. Even the bottles of spring water that Marinov offers to guests are infused with rosewater. Today Bulgarian rosewater is exported to season scores of recipes across the Islamic world including Egyptian kunafa, Turkish delight, Indian lassi, Maghrebi ras el hanout and Indonesian sirap bandung. Locals like Kirova also consume roses in syrups and drinks. “Although we don’t eat too much rose jam because it’s bad for your teeth,” she explains.

Back in the 19th century, when Bulgaria pushed for independence from the Ottoman Empire, “the first Bulgarian producers marketed their oil internationally, starting with England,” continues Marinov. Exports did not have to go via Istanbul, the empire’s capital, to Western Europe. “Trading families started to individually establish businesses with France, the United States, United Kingdom and Austria,” says Marinov. Rosa x damascena was even reintroduced back to Turkey in the 1890s—by a resident of Kazanlak.

Planting in the Valley of Roses peaked around 1910 with 9,000 hectares of Damascus roses. After the fall of communism in 1989, “only 1,000 to 1,500 hectares were planted,” frowns Marinov. “These were the critical times.” Now statistics show around 4,500 hectares planted with Rosa x damascena. “Bulgaria is obligated to preserve this production.”

Though it has grown more than fourfold since the end of communism, total planting in the Valley of Roses is still only about half of what was grown at its peak around 1910.

To drive into the countryside around Kazanlak is to understand why the Damascus rose found a safe haven here. The Balkan mountains rise to nearly 2,400 meters, and even in May they remain snow-capped. Their cool breezes act like a refrigerator, giving rose buds extra time to swell their essential components each spring. The Balkans also raise the Tundzha River, which pours crystalline water into a plain packed with volcanic pumice. The resulting soil offers unrivaled depth and drainage—superb conditions for growing roses above all else.

In the middle of the Valley of Roses, rows of Rosa x damascena shrubs are marked with labels in Cyrillic script that translate “experience” and “control.” (The Cyrillic script originated in Bulgaria.) Alongside sits a country villa that contains the Institute for Roses and Aromatic Plants. The scent around the institute is as intense as a department store’s perfume counter. Here a mission is underway to safeguard—and improve—the Damascus rose stock using a “gene fund” of hundreds of bushes plus tissue cultures stored in a nutrient soup.

Ana Dobreva, the institute’s deputy director, is a scientist of scent. Wearing a floral shirt and a huge smile, her passion for the Damascus rose is as infectious as the blousy blooms out front. “Rosa damascena is unique because no other rose has the same qualities,” says Dobreva, who also started picking the rose flowers as a schoolgirl before commencing her 30-year study into rose genetics.

“Rosa gallica has a good oil yield,” explains Dobreva. “Rosa moschata has a different profile of aroma volatiles.” Their hybrid offspring, Rosa x damascena, has the greatest number of identifiable essential oil components—around 300 in all—including terpenes, esters and aliphatic hydrocarbons, all of which grant stronger and longer-lasting scents than any other rose. “Plus a richer number of phenolic compounds,” adds Dobreva. “It’s the relationship between these compounds that makes the best aroma character.” Phenolic compounds also guard against aging and inflammation.

As Dobreva strolls through her latest line of experimental plantings, she distills her institute’s mission. “We select the best samples of Rosa x damascena and work to make them better”—more resistant to diseases, with a larger number of bigger buds, greater yields and improved essential oils.

Would a rose grower from a century ago recognize the institute’s latest cultivars? “Years ago I went to Taif in Saudi Arabia to help their rose production,” Dobreva explains, referring to the hill town in the mountains of western Saudi Arabia that is nicknamed Madinat al-Wurud—the City of Roses—and renowned for its cool, redolent springtime. “Taif has an old population of Rosa damascena and some differences can be recognized, like the number of branches and shape of the thorns. But the genotype is still the same. Rosa damascena is our treasure and we have worked with it for hundreds of years.”

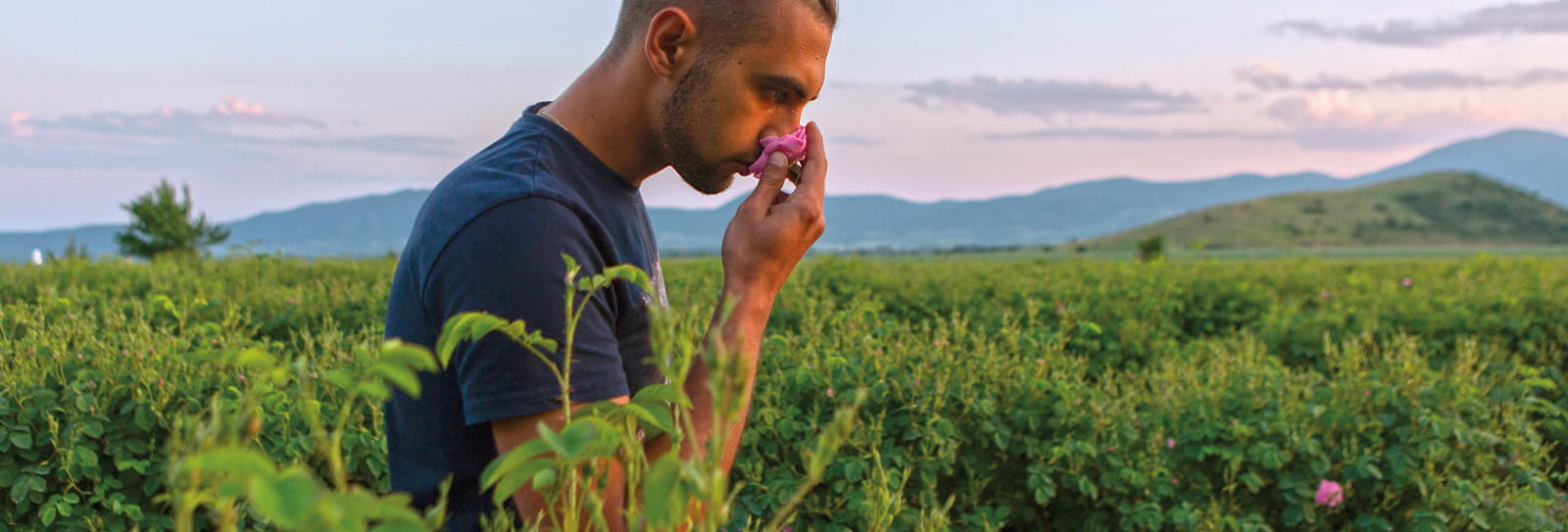

This season’s rose picking has already begun in the fields of Karlovo, a Valley of Roses town 50 kilometers west of Rozovo and Kazanlak. Pink balls of blossom look like party balloons snagged on a thorny forest. The harvest is two weeks later than usual. Climate change has brought erratic weather patterns over the last decade, meaning that picking might be condensed into 30 days rather than the customary 40.

Marchelo Valkov and his father own two hectares of roses. Both have been picking since dawn. “It’s very nice early in the morning,” says Valkov, with the pride of a man whose family have been growing Damascus roses for centuries. Following tradition, pickers often stick the first rose behind their ear, although that is where the romance ends. “It’s hard work because no one can do your job like you do it. You need to go and pick roses and earn your money.” Marchelo Valkov’s roses will be sold to a commercial rose oil distillery, “for around 1 lev per kilo, about 50 cents.”

Most commercial pickers are itinerant and seasonal, moving from one harvest to the next, of roses, cherries, apples, grapes and more. An astute picker can pluck 100 kilograms of buds in a single day. By mid-morning giant sacks will be rushed by tractor to Valley of Roses’s seven large distilleries, including Enio Bonchev, which carries the name of the trader who a century ago pioneered Bulgarian rose oil exports.

“Young people learn rose picking, [but] will roses become part of their family tradition?”

— Filip Lissicharov

The story of Enio Bonchev, now Bulgaria’s leading rose oil exporter, tells the tale of 20th-century rose production. It reads like a Hollywood script. “My great-grandmother ran the business from 1939 to 1947,” says Bonchev’s great-grandson Filip Lissicharov, the current president of the distillery. It was then requisitioned into a state-owned collective farm by Bulgaria’s communist government. In 1967 the distillery’s rose bud storage room, with its ornate stone walls, was turned into a museum. “Nobody in my family spoke about the distillery since 1947,” Lissicharov explains.

When communism collapsed, Lissicharov’s family moved to Los Angeles. “My father, a Bulgarian movie director, tried to find a job as a director of photography in Hollywood,” he continues. “I enjoyed the teenage life of a Bulgarian boy who had not seen Coca-Cola.” When news came in 1992 that the state-owned distillery had been restituted to Lissicharov’s family, “it was a shock.” Lissicharov, who dreamt of becoming an actor or a football player, was not initially pleased. “My parents moved back to Bulgaria and decided to turn it into a working rosewater and oil factory.” In 1997 Lissicharov also moved back to the Valley of Roses, “starting from the lowest level, putting the flowers inside the stills.” Enio Bonchev’s copper stills, which date from the early 1900s, were fired up once again.

Now Lissicharov has added three modern distillery buildings and accompanies government ministers on export trips to the Middle East. “The Gulf countries have big potential,” he says in a serious voice. His nation can undercut some overseas rivals, as Bulgaria’s average wage of 6 euros per hour is the lowest in the European Union. “However Bulgarian rose oil is renowned for its quality, not price,” asserts Lissicharov. “We are pioneers because there’s nowhere to steal ideas from.”

Lissicharov’s main fear is that “young people who learn rose picking from their parents have a telephone in their pocket with Instagram. My question is: Will roses become part of their family tradition like their grandparents? This isn’t like working in a gas station. It’s not a business, it’s our life.”

Alongside changing traditions and weather patterns, a declining population poses a challenge to a labor-intensive industry, where every step must be done by hand. Since 1990 Bulgaria’s population has fallen from around nine million to just under seven million. Many emigrated to the United States, United Kingdom and Germany. Few have returned. The fertility rate, which stands around 1.6, is not enough to sustain the population.

Can roses help rejuvenate a region? In the Valley of Roses, where rose production is the second-largest employer, it appears they can. In 2021 Kazanlak recorded 554 births, a number higher than that of some larger cities. Tonight the selection of a rose queen, part of the town’s three-week Rose Festival, will pack hundreds of guests into an auditorium in an event sponsored by vehicle manufacturers, beauty salons and the Enio Bonchev distillery. Kirova organizes another part of the festival in her village of Rozovo. All across the valley, roses are bringing hope—and cash.

“The rose queen event goes back to 1903,” shouts Galina Stoyanova over the auditorium noise. Stoyanova is Kazanlak’s energetic—and first female—mayor, as well as organizer of the Rose Festival. “In the early years, the event was held for charity, raising funds for the poor young girls of Kazanlak,” she explains. “In this way they received the opportunity to improve their lifestyle.”

“We have a lot of traditions that we show to our daughters and granddaughters.”

—Delka Kirova

The climax of Stoyanova’s festivities is the rose parade in early June. To mark the end of the Damascus rose harvest, residents don traditional dress to dance, sing and throw petals through town. Similar festivals take place in Kazanlak’s sister cities including Grasse in France and Fukuyama in Japan.

Sadly in Syria, rose production near Al-Mrah near Damascus has fallen to an all-time low. Recent conflict has kept farmers from their rose fields, where the Damascus-born poet, Nizar Qabbani, spoke of “tales of the Damascene rose, that depicts the history of all fragrance.” To help rejuvenate the industry, “craftsmanship associated with the Damascene rose in Al-Mrah” was inscribed by UNESCO in 2019. Some Syrians have carried their plants to the Bekaa Valley in neighboring Lebanon. Syrian refugees also harvest the flowers in Cyprus—with the habitual 5 a.m. start.

Back in the village of Yagoda, a short drive east of Rozovo and Kazanlak, there’s a timeless sunset. Rows of Damascus roses are serenaded by birdsong. Butterflies swerve above salmon-pink blooms. Rabbits hop through the wildflowers that tickle the rose bush stems. Alongside these roses sits a gleaming factory that could carry the Damascus rose to the farthest edges of the earth.

The factory belongs to Alteya Organics, a skincare company that in 2004 pioneered biodynamic planting in the region. Business operates on a closed circle. Buds are carried by hand to brand-new stainless steel distilling machines, which—by next year—will be entirely powered by a 100-kilowatt solar array. Over a 24-hour period, these machines spin and steam more oil from each bud than any other method. The remaining rose pulp is composted as fertilizer for next year’s crop. Exquisitely packaged cleansers, organic face creams, toners, lip balms and mother-and-baby products are crafted in a new skincare laboratory next door.

Alteya Organics’ senior sales and marketing manager, Tanya Valeva, translates Damascus rose magic to the Instagram-generation. “There are more than 7,000 different types of roses all over the world,” she explains. “Rosa damascena produces the highest quality of oil with the most complexity.”

Although Alteya Organics exports to over 75 countries, in stores like Whole Foods and Planet Organic, Valeva believes the future is social. “The visual materials are really important,” says Valeva.

Consumers in each country and social media channel are different. “For example, American users look for high-quality functional products with organic certification, but they want to know you’re real, that what you’re doing is not just for the money.” Valeva believes that local education in product development, packaging design and marketing would be beneficial for the Valley of Roses. Then the Damascus rose can complete its final passage around the globe.

Back in her office in Rozovo, globalization is far from Kirova’s mind. The former rose picker is organizing her village’s rose ritual next week. “We will dress in traditional Bulgarian costumes and sing special rose songs before the harvest,” Kirova explains. Another volunteer will clang bells to ward off evil spirits that might damage the ripening Damascus roses. “We have a lot of traditions that we show to our daughters and granddaughters,” concludes Kirova. Through blooms and busts, changing climates and winds of politics, the Damascus rose has been one constant in a life well lived. The future of one of the botanical world’s most successful migrants looks rosy.

About the Author

Rebecca Marshall

Rebecca Marshall is a British editorial photographer based in the south of France. A core member of German photo agency Laif and Global Assignment by Getty Images, she is commissioned regularly by the New York Times, Sunday Times Magazine, Stern and Der Spiegel

Tristan Rutherford

Tristan Rutherford is a 7-time award-winning journalist. His writing appears in The Sunday Times and the Atlantic.

You may also be interested in...

Moroccan Photographer Explores Oasis Culture at Sharjah Biennial

Arts

Moroccan photographer M’hammed Kilito explores richness of oasis culture at Sharjah Biennial

On the resilience of handicrafts in Bosnia-Herzegovina

Arts

The backstreets of Sarajevo’s old town are alive with the repetitive thud of metalworking. In this European capital, with its contemporary high-rise buildings and modern brands, you can still hear the heartbeat of tradition..jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5&cw=480&ch=360)

FirstLook: A Market’s Port of Call

History

Arts

After the war in 1991, Kuwait faced a demand for consumer goods. In response, a popular market sprang up, selling merchandise transported by traditional wooden ships. Eager to replace household items that had been looted, people flocked to the new market and found everything from flowerpots, kitchen items and electronics to furniture, dry goods and fresh produce.