The Muralist–Teakster

- Arts

- History

- Painting

6

Written by Matthew Teller

Photographed by Andrew Shaylor

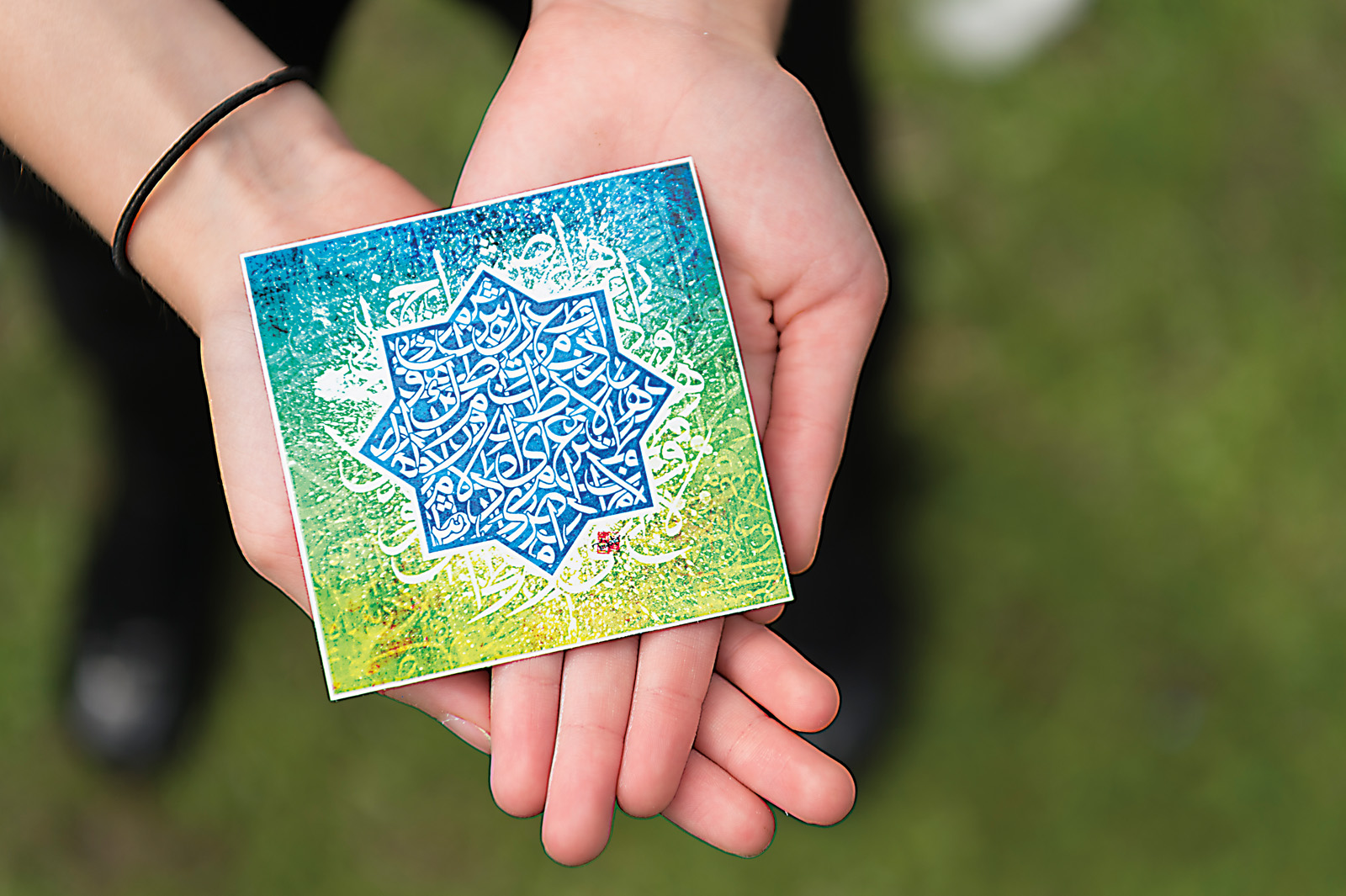

Kneeling on an outdoor drop cloth speckled with blue and green paint, Hatiq Mohammed—known better as the artist Teakster—tapes a star-shaped stencil against a wall.

He wears a dark-blue painter’s jumper, and he’s slung an industrial-grade filtration mask around his neck, ready to protect him from clouds of spray paint. Soft-spoken amid a boisterous group of students, he is guiding the painting of a mural near their school’s playground. It’s the same playground at the same Elmhurst School Teakster himself attended when he was a primary student in Aylesbury, England, a town of about 70,000 northwest of London. Now in his late 30s—he’s reluctant to be more specific—he’s sharing street-smart art with a message of cultural dialog on the walls, streets and galleries of his hometown and the rest of the world.

“Teakster stands out because he values his British heritage and culture, as well as his Muslim culture. He puts the two together, which works really well for our children,” says Elmhurst teacher Viv Woon, who assisted with the mural collaboration.

Elmhurst Co-Head Kirsty Needham, who commissioned Teakster earlier last year, says his involvement at the school excites the students, even though they may not realize how acclaimed the artist is throughout the world. To them, he’s simply an art teacher guiding them on color contrasts and pattern placements.

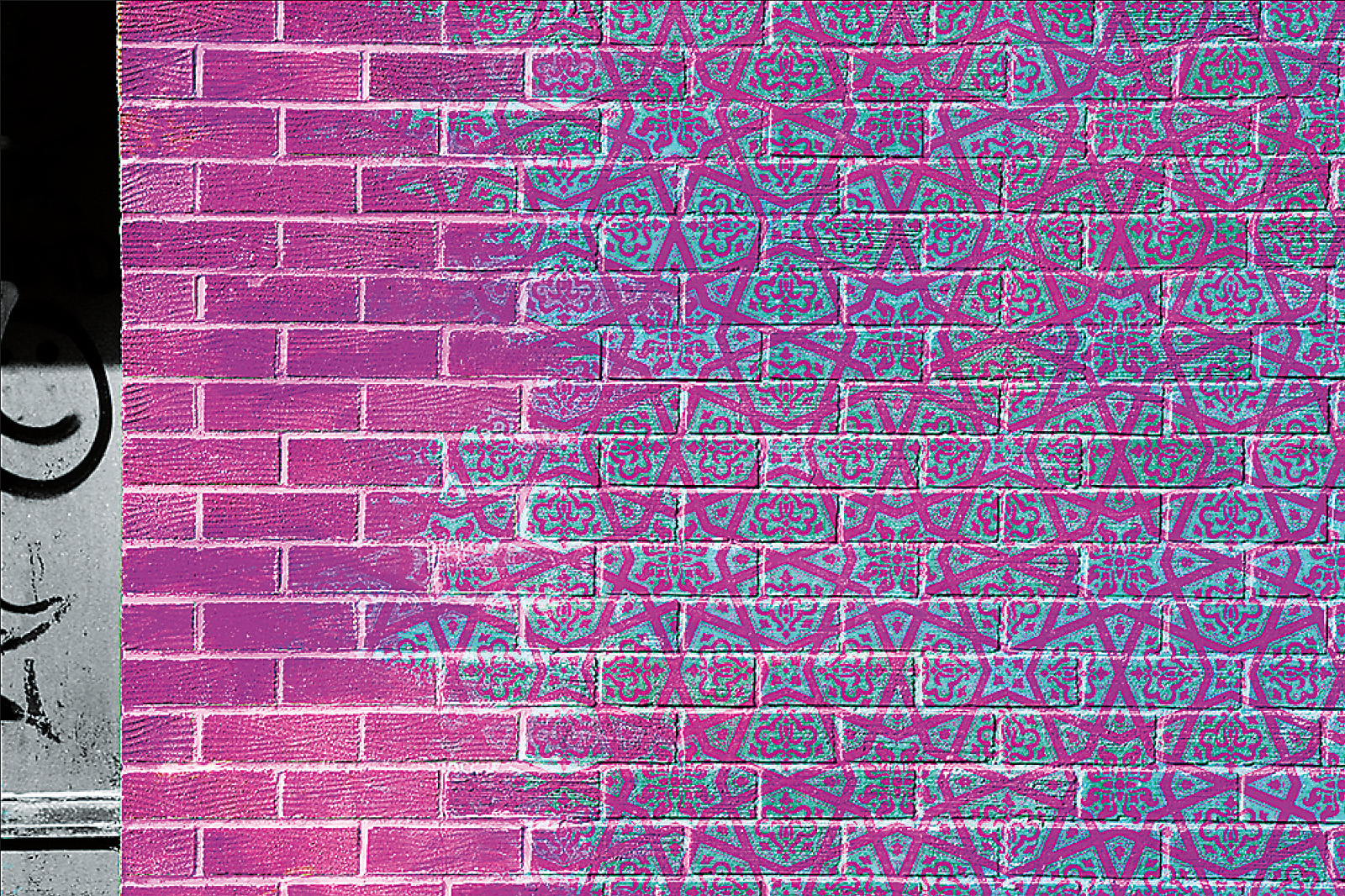

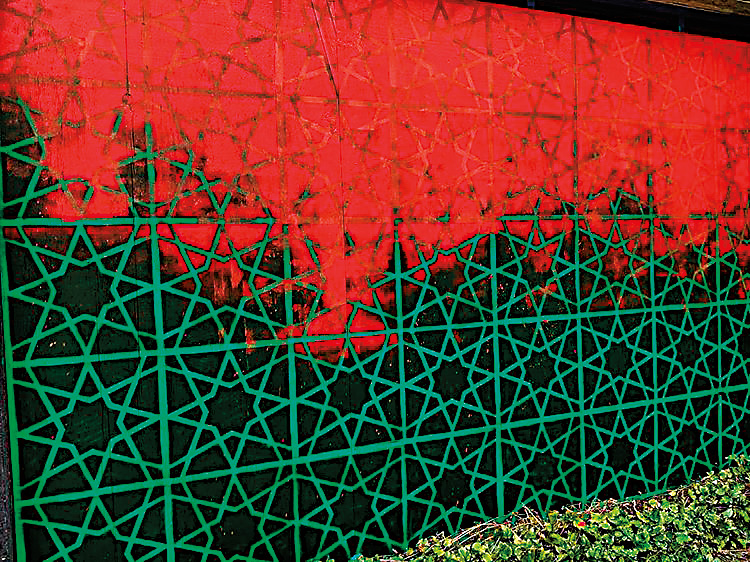

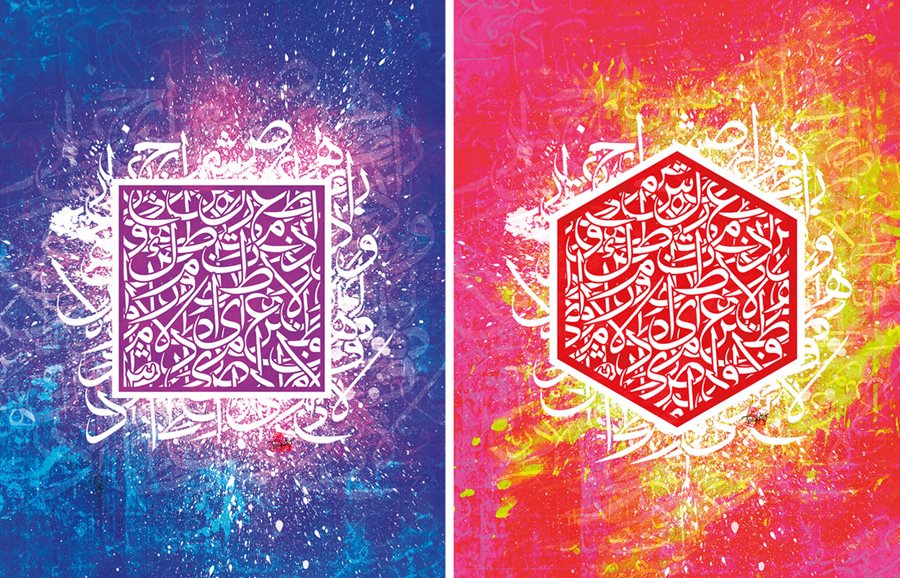

Teakster’s work has been noted for its playful yet disciplined use of classically based Islamic-themed patterns and explosions of color that draw onlookers’ eyes to details of his mixes of Arabic calligraphy, street-style “calligraffiti,” arabesque and geometric patterns that at their edges often fade, appear torn, sliced or set in relationship to solid colors or other patterns.

“My job as an artist is to join communities together, to get people to work in cross-cultural conversation,” he says, speaking carefully, responding only when spoken to, as diffident with words as he is brash with colors.

His designs fuse the raw creative energy of urban graffiti with the poise and heritage of traditional Islamic art.

He takes inspiration, he says, from the traditions and complexities of Muslim artists from past centuries.

“We always look at the history of Islamic art in a nostalgic way. I believe we should look at the past critically,” he says. “We must not ignore the masters of the past. We should use them as a foundation.” His sees his art as playing “an ambassadorial role.”

Teakster’s art has been featured in galleries and group shows in the US, UK, UAE, Malaysia and more. He’s collaborated with better-known artists, including noted Tunisian calligraffiti muralist eL Seed. Teakster, says eL Seed, is “always willing to explore a new medium and new tools” that result in “new narratives” for Muslim communities.

Teakster explains that his name is a play on Hatiq, his given name from his parents, who immigrated to Aylesbury from Pakistan in the 1970s. After settling, his father worked in a local factory to support the family.

Neither his father nor mother, he recalls, particularly supported his youthful artistic pursuits, at least not as a career path. But he persisted and found opportunities to create and showcase his work while working other jobs.

courtesy of teakster

“I had all this pent-up creative anger and energy,” he says, remembering nights when he would go home and reimagine designs he had completed for clients earlier in the day.

Through the years, Teakster has cultivated a personal style that fuses the raw energy of urban graffiti with the poise and elegance often found in traditional Islamic art. He views this careful synthesis of esthetics as an opportunity to embrace the past and couple it with contemporary styles.

“Islamic art is about the future. I evolve classic design techniques and give them a contemporary spin,” he says.

“I believe as an artist you have a social responsibility to bring people together.”

—Teakster

For years his work has garnered recognition for both the sophistication of technique as well as the messaging behind the symbols.

Teakster says he is motivated by the idea of unity, and the peace that comes with it, rooted in Islamic cultures and traditions.

Olu Taiwo, curator of last year’s exhibit I Matter, at Babylon Gallery in Ely, UK, chose Teakster as one of 15 showcased artists. He says it was a “fantastic experience” to see how Teakster “harmonizes Middle Eastern artistic traditions and modern techniques inspired by his British upbringing” to create not only visually striking public art, but art that “captures why religion should matter to those who may not be religious.” That, Taiwo says, “was an inspiration.”

Teakster has also collaborated with Chinese master calligrapher Haji Noor Deen Mi Guangjiang, and it’s through such international projects, with artists who share similar fundamental goals, that Teakster seeks to make the world more peaceful through artistic expression. And the more he can carry Islamic patterns and script into everyday visual culture, the better, he says.

“I want to really push this movement, this minirenaissance of Islamic art, reusing Islamic art for modern times,” he says. “I would love to see this art go mainstream, to see an ordinary ad for an ordinary product that uses Islamic design because it’s beautiful.”Art, he adds, “can break down barriers better than any interfaith dialog. Islamic art is not beautiful because it’s Islamic. It’s beautiful because it’s universal.”

“The best thing is everyone gets to collaborate, and nobody feels left out,” says one girl. Another adopts a serious tone: “I like using spray cans without it being illegal.”

“It’s inspirational,” says Needham, “to have such a great, positive role model of someone who’s gone out from here into the world and made it a more beautiful place.”

About the Author

Andrew Shaylor

Andrew Shaylor is a portrait, documentary and travel photographer based just outside London and has visited 70 countries. He works with a variety of magazines and has published two books, Rockin’: The Rockabilly Scene and Hells Angels Motorcycle Club.

Matthew Teller

Matthew Teller is a UK-based writer and journalist. His latest book, Nine Quarters of Jerusalem: A New Biography of the Old City, was published last year. Follow him on X (formerly Twitter) @matthewteller and at matthewteller.com.

You may also be interested in...

Why Collectors Matter: A Conversation with Arts of South Asia’s Coeditors

Arts

In Arts of South Asia: Cultures of Collecting, coeditors Allysa B. Peyton and Katherine Ann Paul draw us into the personal, institutional and political dynamics surrounding objects that have journeyed from South Asia India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Bhutan to museums abroad and, in one case, undergone repatriation.

Bibi Zogbé: The Flower Painter

Arts

Except for a rare self-portrait, Bibi Zogbé painted flowers—exuberant and confident, as well as modern and symbolic, her paintings reflect her life between her native Lebanon and three decades in Argentina.

Vibrant Portraits: A Conversation With Maliha Abidi

Arts

After growing up in Karachi, Pakistan, and moving to California as a teenager, artist and author Maliha Abidi found it difficult to find stories of women who looked like her or with whom she felt she could identify.