In The Marshes Of Iraq

- History

- Arts

- Photography

10

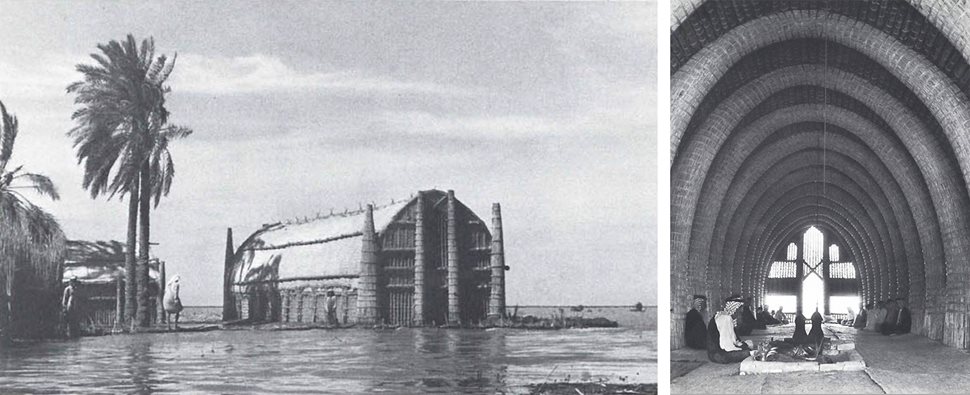

Written and photographed by Wilfred Thesiger

Originally published November/December 1966.

Wilfred Thesiger has never been at ease in today's world. As a boy in Ethiopia he couldn't wait to go wait to go into the jungle alone, As an adult he has spent most of his life in a restless quest for that deep, elusive satisfaction which for some men can be found only in those harsh, wild places of the world described by author William Mulvihill as "the great blank spaces where men died for uncomplicated reasons: thirst, hunger, heat and cold."

Thesiger first explored one of those blank spaces in 1931. On vacation from his studies at Oxford, he led a safari into the Danikil Desert in Ethiopia, an area where primitive tribesmen killed most strangers on sight and castrated the bodies. Later he served as a political officer in the wild Darhur area of the Sudan, During leave and on holidays he explored sections of the Saharan and Libyan deserts. Instead of satisfying him, however, those experiences merely whetted his appetite for more and aggravated his dissatisfaction with civilization. "I hated the calling and the cards, I resented the trim villas ... the meticulously aligned streets," he wrote. "I wanted colour and savagery, hardship and adventure."

Since adventure and hardship are rarely the lot of a political officer, Thesiger eventually resigned, frustrated and unhappy. Then, toward the end of World War II, the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations asked him if he would cares to try to track down the breeding grounds of the desert locust. These grounds, he was told, were thought to be in the Empty Quarter of Saudi Arabia, one of the largest, hottest and, at that time, most remote, deserts of the world. For Thesiger it was the answer to a prayer. "All my past," he wrote, "had been but a prelude to the five years that lay ahead."

As indeed it was. Only a man who had spent most of his life in the wilderness, a man who rejoiced in the challenges of a savage land, could have survived those next five years. Living and traveling with the Bedouins, Thesiger explored the Empty Quarter from one frontier to another. He crossed and recrossed the area from east to west and west to east. On foot and on camel-back he traveled some 10,000 miles. He was "always hungry, and usually thirsty." He knew exhaustion and fear and the constant demands of "an alien people who made no allowance for weakness."

It was, Thesiger wrote later, "a hard and merciless life." Yet for him it was not a "meaningless penance," but rather a deeply satisfying experience which gave him a "freedom unattainable in civilization" and "the peace that comes with solitude." Not only did he accept hardships; he was unwilling, perhaps even unable, to give them up.

As it turned out, however, Thesiger had not escaped civilization; he had merely outdistanced it. Toward the end of his wanderings it caught up with him in the form of seismic exploration parties searching for oil in the most remote corners of Saudi: Arabia. "I went to Southern Arabia just in time," he wrote. "If anyone goes there now looking for the life I led, they will not find it ..."

Thesiger left the desert soon after to return to England and write Arabian Sands. But driven by an inescapable restlessness he was soon off again, this time to climb and ride through peaks of the Karakoram and the Hindu Kush mountains. From there he moved on to the oaken forests and deep gorges of Iraq's Kurdistan. Then, in 1951, he rode south to the Marshes of Iraq.

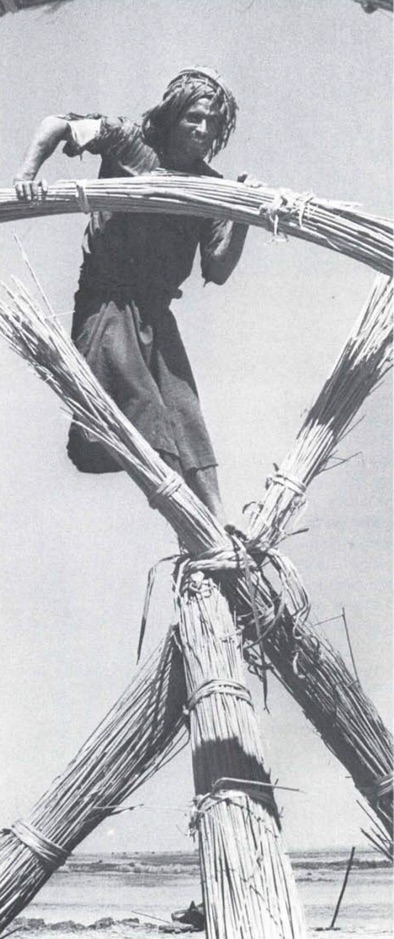

The Marshes of Iraq comprise one of the most interesting areas in the world. Drenched for centuries in the spring overflows of the historic Tigris and Euphrates rivers, they consist of some 6,000 square miles of reedbeds, lakes, bulrushes, canals and sedge. On the fringes of these Marshes, in historic and prehistoric Mesopotamia, civilization after civilization rose and fell like castles of sand on a turbulent shore: Sumerian, Assyrian, Chaldean, Persian, Greek, Roman and Arab. With each wave of conquerors, thousands of refugees fled into the trackless Marshes. It became, for a time, a sort of no man's land and a center of rebellion from which warriors sallied forth to battle whatever ruler then held sway in the Euphrates region. But as Iraq itself dwindled in importance—after the final devastation of the Mongols—so did the Marshes.

Eventually there remained a curious mixture of Occidental and Oriental peoples. Some traced their lineage back to Alexander the Great, some to the Romans, others to Genghis Khan, and the Arabs. And of them all it was the Arab conquerors who left the deepest imprint on the Marshes. Shrugging off the glories of Parthian and Persian power, ignoring the fame of Rome and Greece, the Marsh people adopted Arabic as their tongue, Islam as their religion and the Bedouins as their heroes. Thus, hundreds of miles away from the sands of Arabia, in a land as alien to the Bedouin as the tundras of Canada, there grew up a culture based almost entirely on the ideals and beliefs of the peoples who inhabit the Empty Quarter.

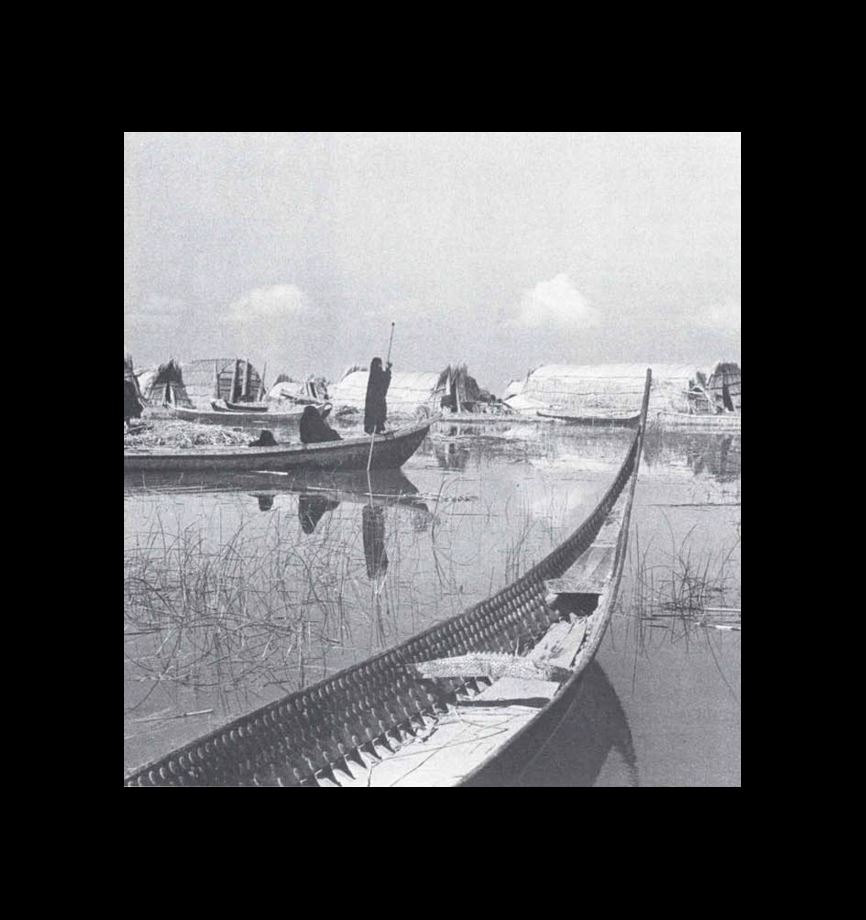

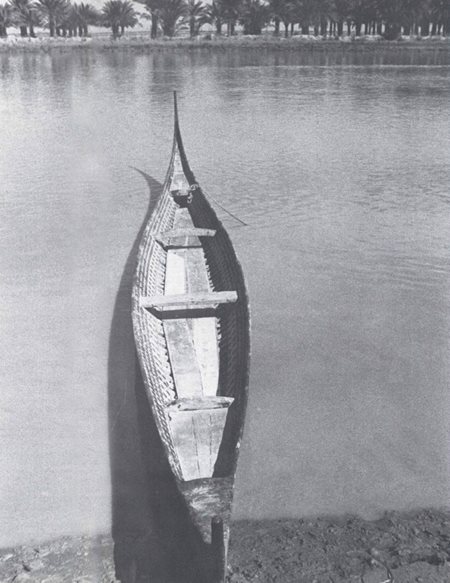

Thesiger had never visited the Marshes before and the first impact was strong and lasting. "Memories of that first visit to the Marshes," he wrote, "have never left me: firelight on a half-turned face, the crying of geese ... canoes moving in procession down a waterway, the setting sun seen crimson through the smoke of burning reedbeds, narrow waterways that wound still deeper into the Marshes ... reed houses built upon water, black dripping buffaloes ... stars reflected in dark water, the croaking of frogs, the stillness of a world that never knew an engine. Once again I experienced the longing to share this life, and to be more than a mere spectator."

"Four years later, at the height of the floods, I happened to be crossing a great sheet of flood water, twelve miles wide and six feet deep, that covered the desert along the tees tern edge of the Marshes... Ahead I could just discern a line of palms, perhaps six miles away, marking the village for which we were bound. Behind us, the reedbeds were no longer in sight ... By the time we reached the village large waves were breaking on the shore, and the palm trees were bending to the force of the gale."

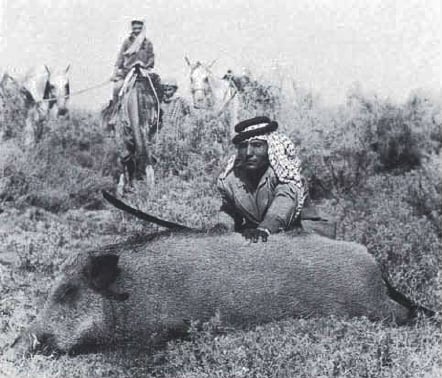

Six months later Thesiger returned to the Marshes to live. Captivated by the wild, free existence of the Marshes, as he had been by a similar life in the Empty Quarter, he wandered through this vast region off and on for seven years, staying first with this tribe, then with that, paddling his long, graceful canoe through narrow canals that curved in an eerie silence among towering reeds, hunting the huge, razor-tusked boars lurking in the reeds by the hundreds, and healing the infections and diseases of the Marsh tribesmen.

It was not a pleasant existence. He was plagued by mosquitoes. He suffered the appalling heat and humidity of the summer. He hunted constantly. He worked unceasing as a doctor. But it was what he wanted—a free life in a land where great beds of huge, pale gold reeds reached up out of calm lakes; where nearly every villager held out a welcoming hand; where ducks and cormorants and herons rose in vast flocks to the skies; where, in sum, a man could be free.

In these years Thesiger made friends and enemies, faced danger, hardship, suffocating heat and shivering cold, and got to know the Marshes as almost no one else ever has. Then one day in 1958 he had to return to Great Britain. He had planned to go back to the Marshes, but in his absence the political situation erupted. When the upheaval ended, he found himself barred from Iraq and the Marshes closed to further visitors. With little chance of ever returning there, he began, reluctantly, to sum up and set down his experiences. The result was the book The Marsh Arabs, from which these excerpts and photographs are taken.

—THE EDITORS—

You may also be interested in...

FirstLook: Ramadan’s Lanterns

Arts

In the March/April 1992 issue, writer and photographer John Feeney took AramcoWorld readers on a walk through the streets of Cairo during Ramadan.

FirstLook: Rain in Fayoum

Arts

I took this photo during a rainy day in November 2018 from the window of my family home in Fayoum, Egypt, located about 100 kilometers southwest of the capital. It hardly rains but a few times in the year in most parts of Egypt, and when it does, it is always something special, bringing Joy and happiness particularly for the local children.

FirstLook: Ramadan Picnic

Arts

On a warm June evening, people gathered at a park in Bethesda, Maryland, for a community potluck dinner welcoming the start of Ramadan.