Histories on a Plate: Reflections on Food and Migration

- Food

- History

12

By J. Trevor Williams

As we celebrate our 75th anniversary this year, AramcoWorld has launched a six-part series that reflects on the connections and impact the publication has generated over the decades. AramcoWorld’s approach to intercultural bridge-building has been integral to its mission since its founding. In the sixth and the final part of the series, we have focused on food, a topic that has been integral to the publication and a powerful tool in connecting global cultures. In it we hear from contributors who have written about diverse cuisines, the origins of our everyday ingredients and historical ties between food and societies around the world.

—AramcoWorld Editorial team

Read more from our 75th anniversary series.

Part 1: Reflections on Connections

Part 2: Reflections on Journeys

Part 3: Reflections of Knowledge

Part 4: Building Cultural Connections

Part 5: Reflections on People

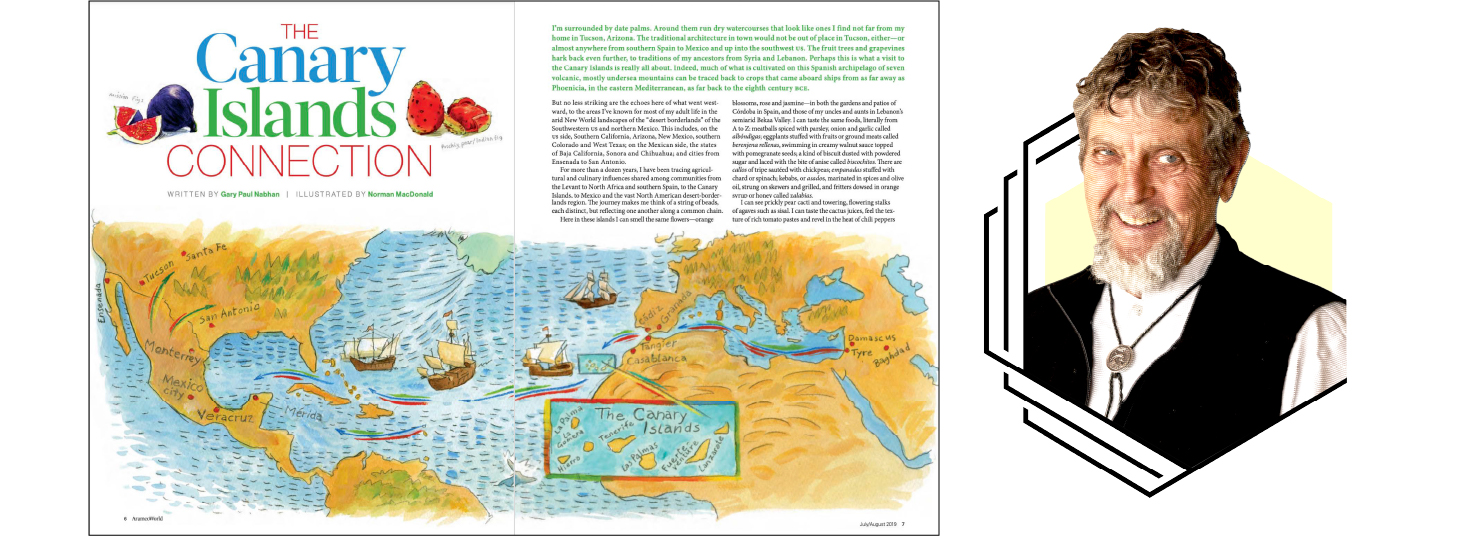

Lebanese American writer Gary Paul Nabhan’s 2019 article “The Canary Islands Connection” traced the archipelago’s breadcrumbs of culinary provenance.

When Gary Paul Nabhan decided to take a sabbatical in 2018, he traveled from the southern United States to Beirut to spend time with cousins, a common pastime as the Lebanese American writer and ethnobotanist gained a deeper connection to his roots.

Stopping at an Armenian restaurant in Beirut, he ordered moussaka, a traditionally Greek eggplant casserole, not expecting a culinary breakthrough.

What arrived, however, was a revelation—a stunning facsimile, with some key tweaks, of a dish he knew well from the US-Mexico borderlands.

“I thought they’d brought me the wrong dish because it looked like chile peppers in walnut sauce,” Nabhan says, referencing chiles en nogada.

But the color and complexity that Mexicans achieved with achiote and annatto the Armenian chefs had accomplished with turmeric and sumac in a cream sauce over, yes, a stuffed eggplant.

“In every way it was identical, and that was so powerful—an aha moment—that when people move to new countries they may not get the exact same ingredients, but they’re using the same script.”

The occurrence crystallized what Nabhan had noticed since settling in the US borderlands in his 20s—that desert cuisines of the New World were inextricably linked with the Old.

That realization undergirded Nabhan’s 2019 AramcoWorld piece: “The Canary Islands Connection,” in which he explores how the archipelago off the coast of Africa became a point of departure for plants and produce, first carried to Al-Andalus by Islamic rulers, then brought across the Atlantic by Spanish colonists to the semiarid lands they would occupy.

Even while hiding their identities, forcibly converted Muslim Moriscos, as well as Jews known as Conversos, didn’t forget where they—or their food—came from, and that’s evident from the fruits, livestock and even the surnames in the region today.

The Canaries, Nabhan writes, were beads in a “necklace of history strung across a hemisphere,” providing breadcrumbs of culinary provenance for the curious observer to trace.

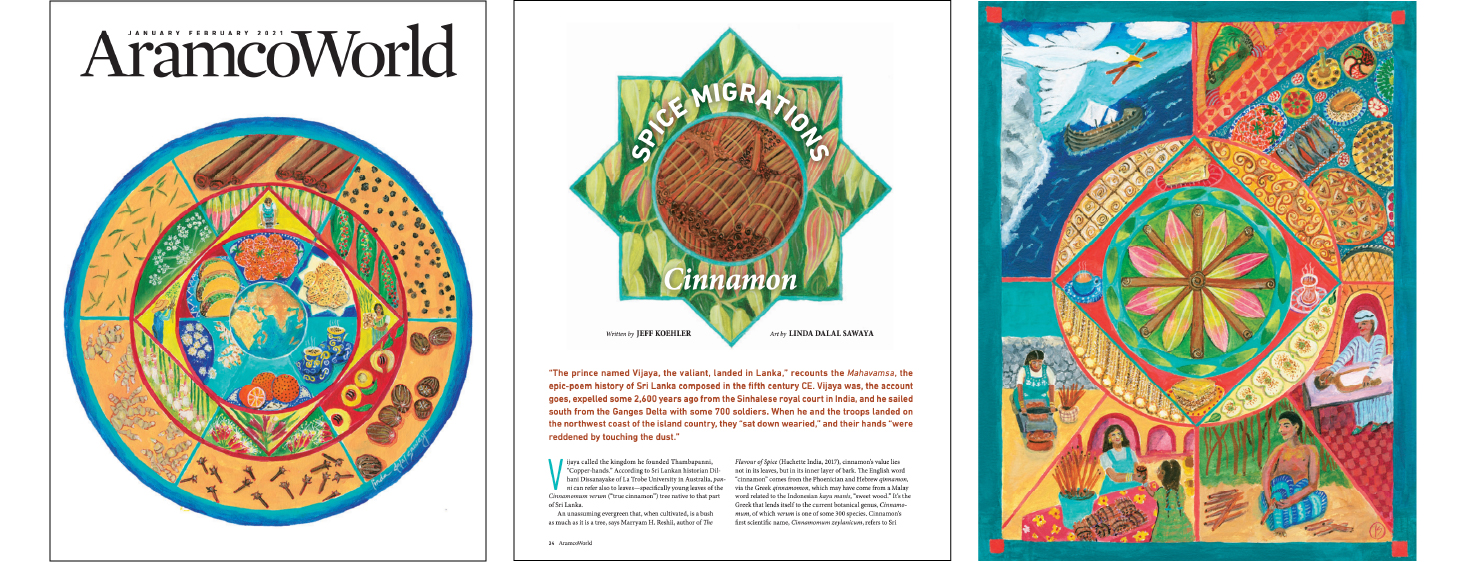

AramcoWorld’s 2021 “Spice Migrations” series, by cookbook author and journalist Jeff Koehler, looked at food as a “mosaic of culture.”

For much of its 75-year history, AramcoWorld has published stories about food, employing it as an unrivaled means of revealing the world’s interconnectedness. While it’s possible to twist cuisines into the basis for jingoistic rivalries, trace recipes back far enough, and the flow of flavors invariably brings out shared lineages, like a cultural DNA test.

“To write about food is to write about people, politics, history, geography, religion—all wrapped up into the mosaic of culture. Food is such a fundamental expression of culture that it is impossible to separate,” says Jeff Koehler, an accomplished cookbook author and journalist who undertook the Spice Migrations series for AramcoWorld in 2021, in the midst of the pandemic. “What is on our plates is always changing. It is never static. It is a reflection of us—as a people—at the moment. But also of our pasts.”

Diving into the seemingly mundane world of spices like ginger, pepper, cloves and cinnamon was a godsend for Koehler, and not just because he was able to stay connected to the world through virtual interviews.

The exercise also challenged prevailing historical narratives largely gleaned from Western sources, enriching his later work like The North African Cookbook.

“The key was to find a balance between the historical material, often by early Arab historians, and contemporary sources in the countries producing the spices as well as cooks and others who were using them. I was interviewing people in a dozen different countries, often for the same story.”

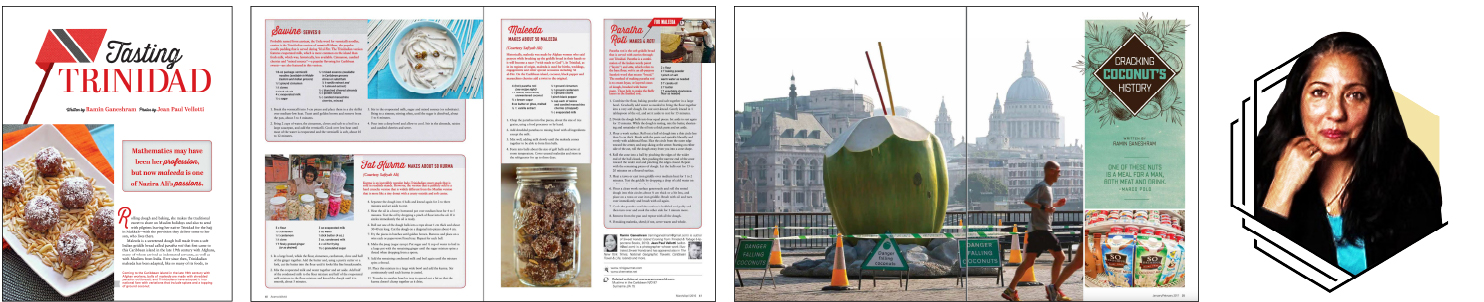

Ramin Ganeshram’s articles “Tasting Trinidad” from 2016 and “Cracking Coconut’s History” from 2017 used food to elucidate Muslim influences on coastal communities.

Ramin Ganeshram, who runs a history museum in her day job, has made a career using food to stir the pot on thorny historical issues that may otherwise be off limits for conversation.

“It is easier to say to somebody: The reason we have barbecue is because of colonization of the Caribbean where barbecue was created” than to pointedly discuss slavery, says Ganeshram, whose novel The General’s Cook is based on a historical chef for George Washington who was renowned for his cooking but remained enslaved.

“I’m very interested in the movement of people, how food was both deliberately and accidentally part of those movements—how that food was combined into something new,” Ganeshram says..

She encountered this dynamic in two AramcoWorld stories she wrote. The first one, “Tasting Trinidad,” where her father grew up, used food to elucidate Muslim influences on the island’s cuisine—and to tell a more complete story of its diversity.

Foods now considered local, she wrote, carry in their names and modes of preparation the “cultural memory” of the societies where they originated. Biryanis from the mosques of Mughal India became meaty rice pelau of today. Similarly, maleeda, sweet dough balls made from roti, originated in Afghanistan but were adapted to local tastes through the use of coconut, clove and cinnamon. Eaten traditionally during Ramada n, the dessert now brings people together across religious lines.

Ganeshram mined a similar vein in her exploration of what she calls “the vanilla of the Caribbean.”

Coconut made its way to coastal communities around the world from its origins in India and Southeast Asia, arriving in the Caribbean by way of slavery and colonialism. It continually elbowed its way into recipes like those Ganeshram was compiling in Cooking Coconut, a cookbook she was working on while producing the AramcoWorld story. Writing for the magazine gave her the time to delve into why, despite its longtime popularity within her multicultural New York community, the US and other countries took longer to more broadly embrace what had become “the global ‘it’ ingredient.”

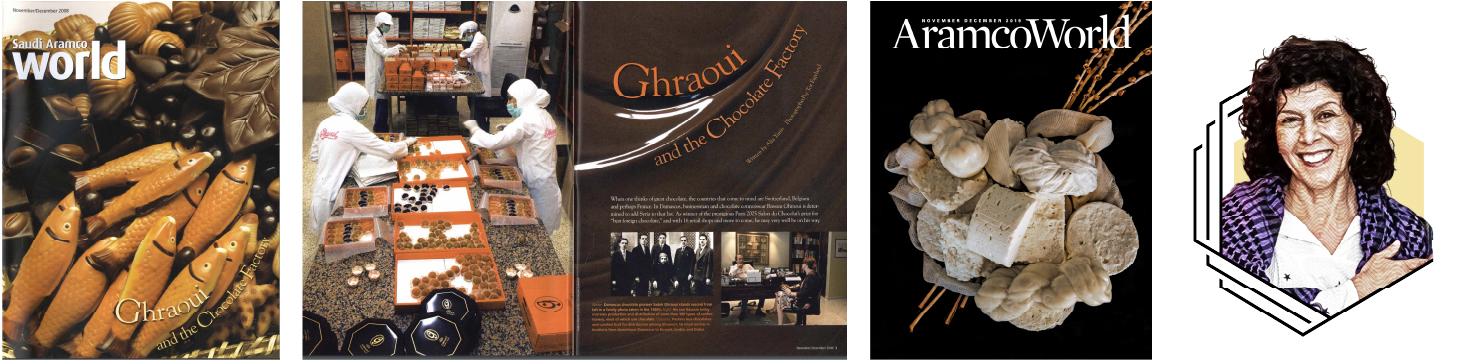

Over 15 years’ worth of stories, food has been “such a large part of the conversation. It was [sources’] way of welcoming me,” says contributor Alia Yunis.

Alia Yunis has tackled similar subjects in the 15 years since she started writing for the magazine with a 2008 cover story on Bassam Ghraoui, an award-winning chocolatier from Syria. Her looks at the mangoes of India, US-grown dates in California and cheesemaking in the Arab world repeatedly underscored why she’d loved AramcoWorld even as a young girl frequenting the library in Beirut: its unabashed depth and relentless focus on underrepresented perspectives.

But Yunis, now a professor and filmmaker at New York University’s Abu Dhabi campus, also found food to be central even to nonfood stories. When covering the world’s most northerly mosque in Norway, locals (non-Muslims) shared with her reindeer and seal meat. In Kyrgyzstan, she bonded with her hosts over maksym, a nonalcoholic fermented grain drink.

“Even though I wasn’t writing about food, it was just such a large part of the conversation,” Yunis says. “It was their way of welcoming me. It was their pride.”

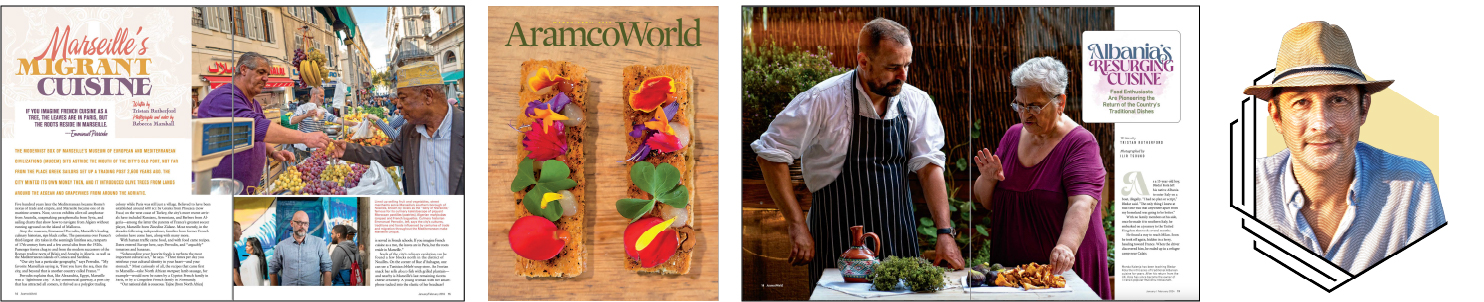

Travel and food writer Tristan Rutherford has given readers a taste of food’s role in rooting people to a place and maintaining their cultural identity.

Perhaps that’s because food plays such a strong role in rooting people to a place and creating—or retaining—an identity, says Tristan Rutherford, a travel and food writer who crafted a category-defining story on the migrant cuisine of Marseille, France, for AramcoWorld.

“In places like Marseille, food has given people a belonging to a new place by carrying their recipes with them. Safeguarding your favorite foods is perhaps people's most important cultural act,” Rutherford says. "This has created a sense of place when you've been uprooted, a refugee, or you're a migrant, or you've been displaced by war, or fall in love with someone, or got a job in a new place. Bringing that food gives you a tangible link to your heritage and your past, something to give to your children.”

That’s what happened with Albania, where in the 1960s the communist government outlawed expressions of religion. People sourced ingredients for foods like halva, a Ramadan staple, months in advance and made it behind closed doors. Many who left the country after the fall of communism in the 1990s eventually came back. They include the Kola brothers, profiled in Rutherford’s “Albania’s Resurging Cuisine.” The pair worked their way to London and ascended the city’s culinary ranks, working in kitchens helmed by Michelin-starred chefs. Now they’re back in Albania preserving the country’s culinary traditions.

Meanwhile, some countries have adopted the dishes of their immigrant communities. Rutherford points out how his native Britain embraced a South Asian dish, chicken tikka masala, as an example.

“This is a hackneyed Bangladeshi dish. It doesn't really exist back in India, Bangladesh and Pakistan, where Britain’s had huge migration from, but it was like a curry made for the British plate. It's now our national dish, even more than fish and chips.”

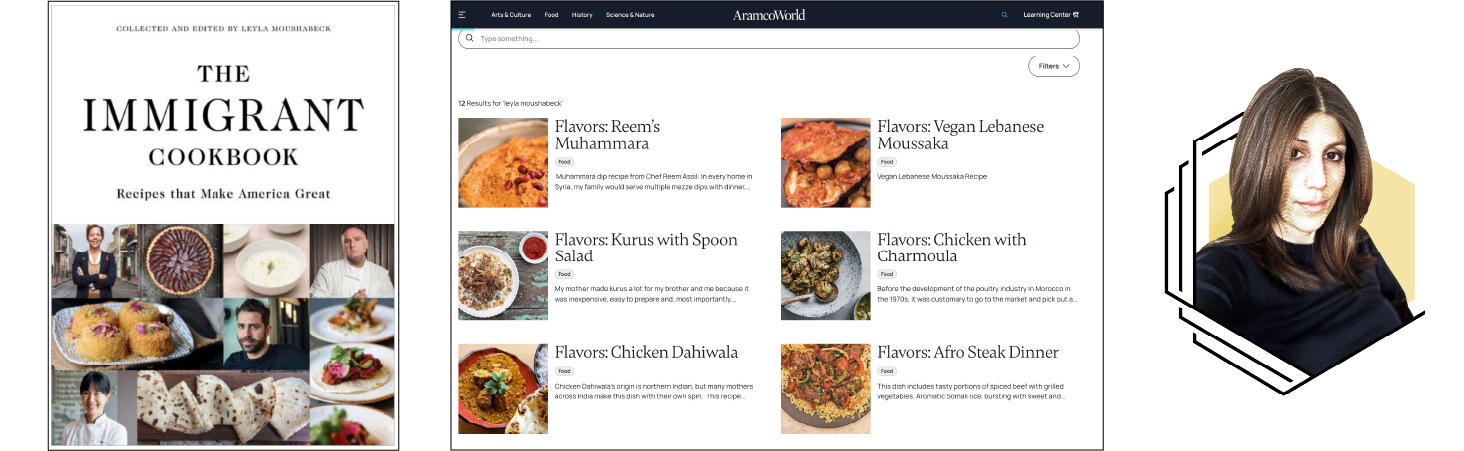

Leyla Moushabeck is a cookbook editor with Interlink Books, which initiated a partnership with AramcoWorld to publish recipes that reflect stories of empowerment.

Food can be a portal for present-day activism as well as historical reflection, says Leyla Moushabeck, cookbooks editor for Interlink Books and the author of The Immigrant Cookbook: Recipes that Make America Great.

While recipes and cookbooks seem innocuous, they tell the story of who has traditionally been empowered, which is one reason the Palestinian-owned imprint in the US initiated a collaboration with AramcoWorld to publish them in the magazine. The agreement, she believes, was hashed out over a meal at Mama Ayesha’s, a go-to institution for Middle Eastern cuisine in Washington, D.C.

“In this moment when we are all painfully aware of imbalances of power in our society, we uplift the cultures and lived experiences behind the foods we love and ask our uninitiated readers to reflect on who is given the platform to represent them, and the lens through which our stories are so often presented,” Moushabeck says.

While food has been an editorial focus of the magazine for many decades, AramcoWorld in 2018 began publishing its recipe section, Flavors, and has kept it in the front pages of the magazine since.

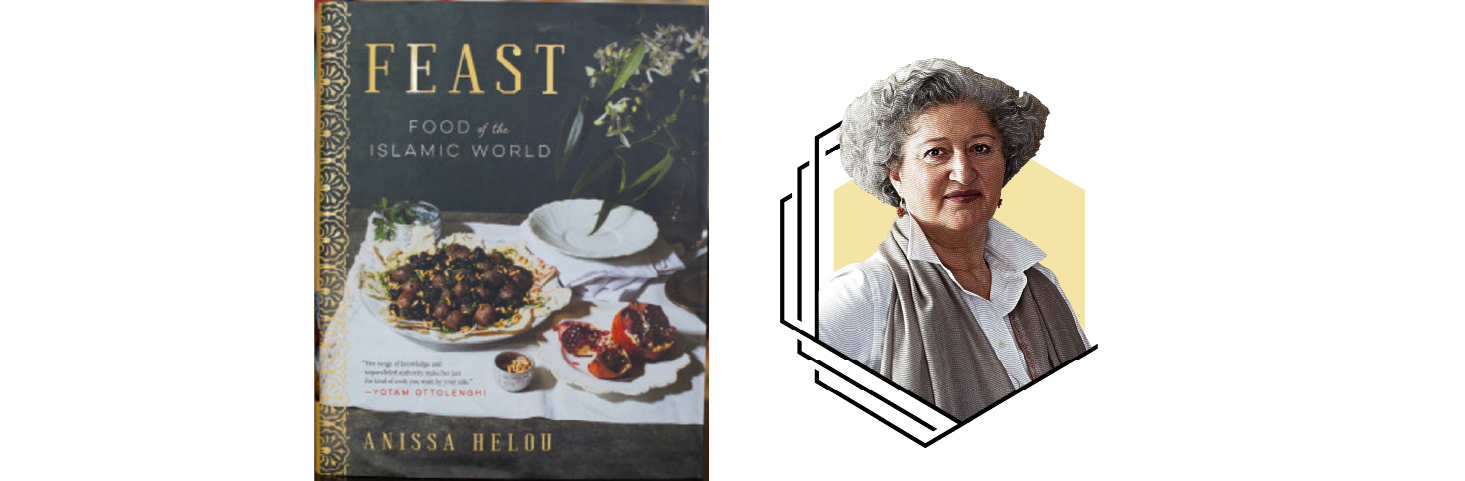

Contributor and cookbook author Anissa Helou says, “Food is culture, and through it and its rituals, you come to understand a country and its people.”

There’s still plenty of room to educate the world about the diversity of foods in the Middle East and the Islamic world, says Anissa Helou, a contributor of recipes like Flavored Camel Meatballs and the author of Feast: Food of the Islamic World, a cookbook reviewed by AramcoWorld in 2019.

“In some countries, like those across the Levant, the culinary repertoire presents similarities, in which case it makes sense to talk about while outlining the variations on the same dish from one to another,” Helou says. “The same for the [Arabian] Gulf and to a certain extent North Africa. However, when it comes to the whole Middle East, you cannot lump the Iranian culinary repertoire together with that of Lebanon or that of Turkey.”

Islam, with its dietary restrictions and common religious calendar of Ramadan and Eid, creates a semblance of unity, but it would be inaccurate to assume too many shared characteristics, given the cultural variance of majority-Muslim countries: “Indonesian food is very different from that of Senegal or that of Saudi Arabia, to name a few,” Helou says.

She adds that it’s important to continue publishing recipes in AramcoWorld—even if many readers never cook them—as they introduce nuance into the conversation the magazine is aiming to foster on broader cultural connections.

“Food is culture, and through it and its rituals you come to understand a country and its people. As such, it is important to preserve culinary lore for future generations,” Helou says.

Beyond this, circulating recipes and the human stories behind them can help fight the homogenization and dumbing-down of traditional cuisines as the world grows increasingly integrated, says Nabhan, the scholar, who just finished another of his own cookbooks: Chile, Clove and Cardamom, which tracks how desert cuisines have influenced the world’s palate.

“Resist,” Nabhan admonishes readers and cooks. “Resist with your mouth and your heart.”

You may also be interested in...

Muhalbiyat al-sagoo - Sago and Lychee Pudding

Food

Obtained from the trunks of various palms, sago is used across Asia as a thickener for soups and stews and to make pudding. You can substitute other soft, sweet fruit like plums or pineapple, but the sweet juice of the lychee blends very well with milk. This is an exotic take on the traditional sago pudding popular in Gulf cuisine, made with sago, sugar and spices.

The Bengalis are famous for their “chops,” or potato croquets eaten as snacks with tea.

Food

The Bengalis are famous for their “chops,” or potato croquets eaten as snacks with tea.

Flavors: Cracked Wheat and Tomato Kibbeh

Food

Sitting on the beach with my feet in the sand, listening to sounds of Lebanese pop music drifting through the air, watching children play in the water, eating simply cooked line-caught fish with this beautiful vegetarian tomato kibbeh. I don’t know how you could top it.