Lives in Clay: A Conversation with R. Neil Hewison

- Arts & Culture

5

Written by Kyle Pakka

He never planned on Egypt. Having learned Swahili while studying linguistics at University of York, United Kingdom, R. Neil Hewison expected his first assignment with the international charity organization Voluntary Service Overseas would be in East Africa.

Instead, in 1979 he found himself teaching English in Fayoum City, a quiet town of horse-drawn buggies about 100 kilometers southwest of Cairo and a fertile oasis west of the Nile. “Almost immediately I was invited into people’s homes in little villages,” Hewison remembers. “It was a great introduction to the culture. I loved it and wanted to stay.”

Intrigued by the Fayoum oasis, Hewison published his first book, The Fayoum: History and Guide, in 1984. Although he spent the following decades working for the American University in Cairo Press, Hewison built a home in Tunis, Egypt, a Fayoum village famous for modern pottery.

After his 2017 retirement, Hewison zeroed in on Fayoum pottery as exemplified by modern pieces in Tunis, as well as pottery traditions in the villages al-Nazla, just southeast of Tunis, and Kom Oshim, less than an hour east.

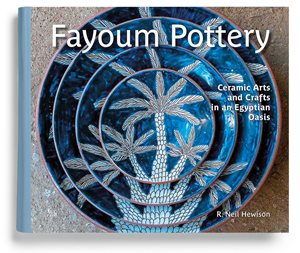

AramcoWorld recently spoke with Hewison about the resulting book, Fayoum Pottery, Tunis life and the changing fortunes of Fayoum’s ceramic artisans.

Why is Fayoum pottery—both traditional and modern—worth documenting?

Pottery is produced all over Egypt—in Old Cairo, in the Delta, in Upper Egypt—so in that sense, Fayoum is not special. But Tunis pottery is special because it has become a new way to sustain and bring prosperity to a previously impoverished rural community, and also because it has found such an eager market for handcrafted folk-art products, first in Cairo and then around the world. Kom Oshim is keeping alive a long tradition of crafting enormous pots, while al-Nazla pottery is special because the primeval hammer-and-anvil technique perpetuated there is now not found anywhere else in Egypt or, as far as I have been able to discover, in the world.

What were you surprised to learn?

I already knew Tunis pottery pretty well, but the size of the kilns at Kom Oshim—some 4 meters square [in surface] and 4 meters in height—was a shock. The first time I visited the workshops, in 2020, they were building up the fire in the pit below the kiln, and it was like those old movies where they shovel coal into the engine on a steam train. They can get hundreds of these tall pots into these kilns at a time.

The other village, al-Nazla, was more of a rediscovery. After 40 years of visiting this place, I still find it fascinating to watch the potters start with a ball of clay and hammer it into a sphere. There’s nowhere else in Egypt where they make pottery like that.

While Tunis is known for modern pottery from the Tunis Pottery School founded by the late Swiss ceramicist Evelyne Porret in 1990, the al-Nazla and Kom Oshim pottery traditions have been handed down for centuries. Is the craft still being preserved this way today?

Some of today’s potters can trace the craft back through nine generations, but it’s not being passed down as regularly from generation to generation now. Potters in al-Nazla and Kom Oshim love what they do, but their children are being educated, they go to school, they go to university, and the potters want them to have a better life.

What do you think the future holds for these pottery villages?

There’s reason for concern for traditional pottery. When I first moved to Fayoum, everybody had a Kom Oshim pot or an al-Nazla bukla, a big round pot for storing water and keeping it cool, in their house because there weren’t a lot of refrigerators. I had a bukla in my flat. Now everybody has fridges and freezers, and demand has dropped, and that’s obviously a problem.

In Tunis, things are looking up. People started coming for pottery, but now you can go horseback riding, take a boat ride on the lake, and people have opened coffee shops and restaurants. The Tunis Pottery School is still going, and the youngest generation is trying new techniques and designs. I have less hope for the future of al-Nazla and Kom Oshim because they are not as commercial. They’ve got tougher challenges.

After living in Tunis for decades, what does this book mean to you?

Looking back, I was incredibly lucky to be sent to Fayoum. I’ve had so much fulfillment from living here. It’s really nice to present something that gives a sense of what, to me, is a very special place.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for length and clarity.

You may also be interested in...

The Resilience of Craft - Three Exhibitions at Venice Biennale Uphold Legacy of Traditional Arts

Arts & Culture

The Venice Biennale sheds light on lesser-known narratives outside of the international art world.

The Bridge of Meanings

History

Arts & Culture

There is no truer symbol of Mostar, Bosnia-Herzegovina, than its Old Bridge. The magnificent icon of Balkan Islamic architecture was destroyed during the 1992–’95 war—but not for long. Like the multicultural workforce that produced the original hundreds of years earlier, a broad team of architects, engineers and others came together immediately to plan its reconstruction. This summer marked the 20th anniversary of the bridge’s reopening.

Vibrant Portraits: A Conversation With Maliha Abidi

Arts & Culture

History

After growing up in Karachi, Pakistan, and moving to California as a teenager, artist and author Maliha Abidi found it difficult to find stories of women who looked like her or with whom she felt she could identify.