Skate Parks in the Abstract: Analyzing the Alternative World of Abstract Photography

Art

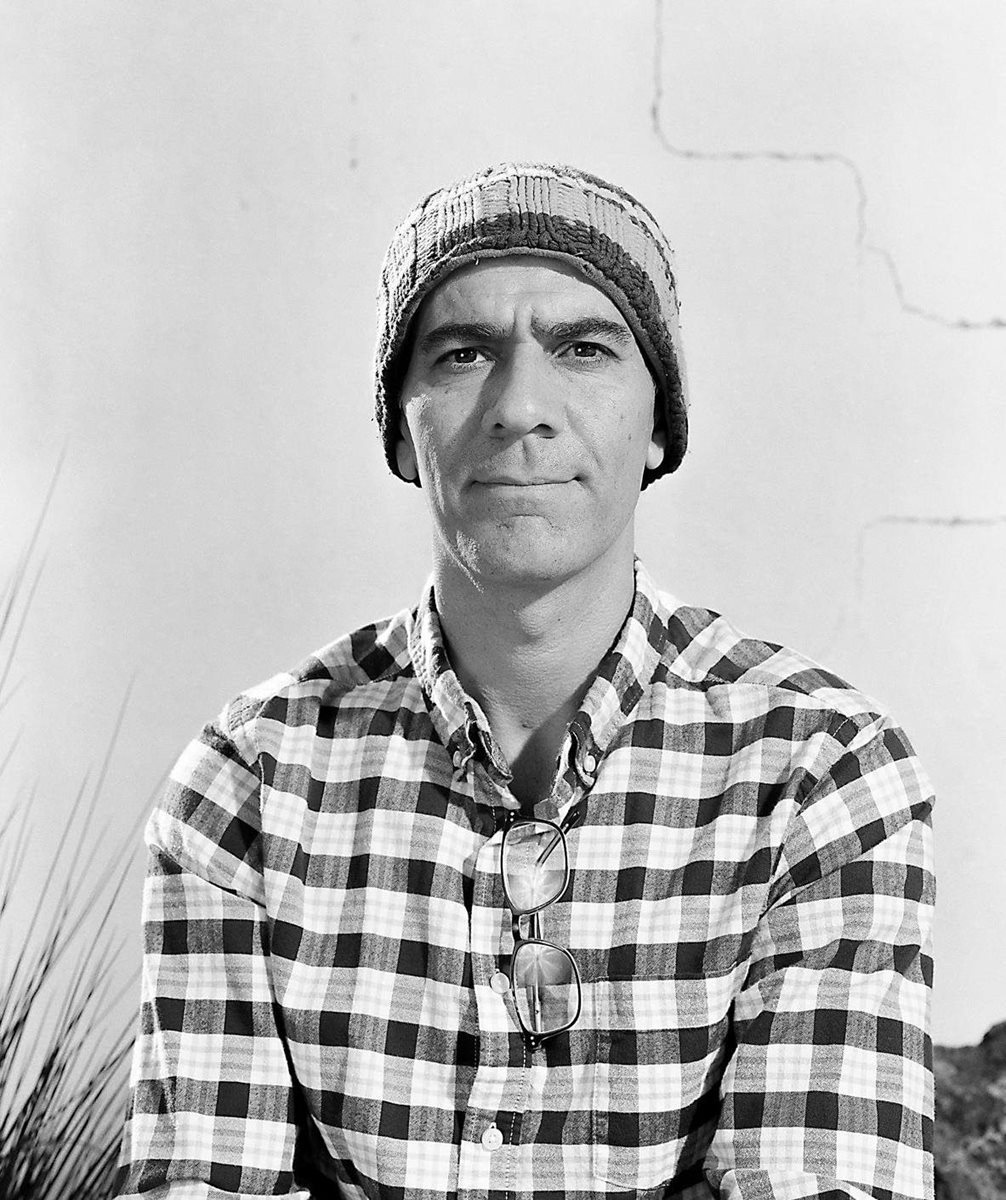

Written by Brian E. Clark and photos courtesy of Amir Zaki.

The following activities and abridged text build off Amir Zaki's Sculpture of Skateparks

WARM UP

Warm up by completing prereading activities.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 15 MINUTES ...

Compare a realistic photograph and an abstract photograph.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 30 MINUTES ...

Watch the video “Empty Vessels,” and respond to three of its key ideas, either in discussion or in writing.

VISUAL ANALYSIS

Compare a realistic and an abstract photograph, and then take your own realistic and abstract photos.

Directions: As you read, you will notice certain words are highlighted. See if you can figure out what these words mean based on the context. Then click the word to see if you’re right.

Amir Zaki's Sculpture of Skateparks

When 46-year-old Amir Zaki looks at a skatepark, he sees more than a place to do tricks. He sees a geography in concrete—a landscape of hummocks, valleys, cornices, bowls, twisting riverbeds and waves. He has skateboarded on and off over the course of his life. Now a professor of photography and digital technology at University of California, Riverside, Zaki has embarked on a project to photograph the beauty and mystery of skateboard parks.

Zaki’s ample body of photography have appeared in museums and galleries throughout the US and abroad. Many of his shots transform everyday landscape objects—houses, vehicles, towers, rocks, bushes, or trees—into carefully observed, often austere, graphic compositions. Zaki’s images are unique for their focus on the empty, curvaceous, weathered concrete canvases upon which skaters carve their expressive, ephemeral lines.

Question: How does Amir Zaki’s photographs of skateboard parks compare to the photography of magazines such as Thrasher?

Zaki’s photos are unique for their focus on the empty concrete shapes of skateparks. Magazines like Thrasher were more action oriented, showing people skating on streets, sidewalk's, handrails and pools. Photographs focused on the lone skaters.

His images contrast sharply with the action-oriented skateboard photography that had helped popularize the sport in the 1970s and 1980s. Like the sport, photographs portrayed rugged renegades adapting streets, sidewalks, handrails, plazas and pools into stunt arenas. Popular magazines such as Thrasher have shown iconic action shots focused on lone skaters, often shirtless, sometimes barefoot, almost always sun bleached.

As a youth, Zaki and his friends took to zipping around streets and “catching air” off plywood backyard ramps. It was part of the culture and identity of growing up in Southern California in the 1980s. Both his parents were open-minded about Zaki’s youthful pursuits and choosing art as a career. His late father, a plant pathologist and Muslim, had come to the US from Alexandria, Egypt, and he met his mother, an educator and a Catholic, in Minnesota.

A trip at age 11 to Egypt with his father expanded Zaki’s worldview. He learned there was much more than his suburban neighborhood. By being in a foreign land and not knowing the language or customs, he learned humility and patience, which carried over to his career as a teacher. This kind of openness, it turned out, resonates within skateboard culture, where all you needed was a board to be accepted.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the first skateparks were based on bowls, much like the empty backyard pools in most California homes. These first skateparks featured fast transitions between flat bottoms and high, steep walls. Nowadays, skateparks have developed into complex, layered and infused with dimension and texture. Zaki’s photographs capture parks that have become increasingly elaborate as skateboarding has evolved toward ever-greater athleticism and technical difficulty.

His images contrast with action-oriented skateboard photography.

Question: Describe how skateparks of today differ form the first skateparks of the1980s and 1990s.

Today’s skateparks are complex, layered and infused with dimension and texture. In the past they were nothing more than empty swimming pools.

In the late 1990s, the state of California passed legislation declaring skateboarding a “hazardous recreational activity.” The law freed municipalities from liability for injuries a skater might sustain in a publicly owned skatepark and left the responsibility up to the individual. Beginning in 1998, skatepark building took off. As a result, an estimated 450 exist skateparks in California, more than 3,000 nationwide, and hundreds more worldwide, all serving as both athletic and social hubs.

Aaron Spohn, 60, founded the Los Angeles–based Spohn Ranch Skateparks, which over three decades has built more than 1,000 skateparks around the world. “The dynamic nature of skateboarding inspires artistic shapes that can look like standing waves or canyons or undulating riverbeds,” Spohn says. Skatepark builders gather input from skaters for design ideas, he adds, “then beyond the sculptural aspect to add surface texture with brick or granite or marble to create a truly architectural space.”

While in his early 30s, living in North Hollywood, Zaki was drawn to photographing a skatepark near his home. At dawn, when the shadows were long and skateparks were empty proved to be a great time to take photos. “Early in the morning when I could get down inside the skateparks, and that made the biggest difference in the kind of art I was able to achieve,” he says.

Some of his photographic influences come from contemporary landscape photographers who take photos of everyday structures like water towers, warehouses and other industrial landscapes. “I’m super interested in architecture and how different parts of the landscape are used in contemporary times,” Zaki says. “I look at buildings, and even lifeguard towers, as being sculptural.” He also photographs skateparks as a skateboarder knowing what it feels like to move through that space with his body.”

Question: What are some of Zaki’s photographic influences?

Some influences are contemporary landscape photographers, architecture and , his own skateboarding experience.

After Zaki has found the right spot, he sets up his robotic tripod, which he has calibrated to shoot 25 to 70 photos in sections. Then he downloads the images and arranges them so he can digitally stich them into a huge file that can be enlarged to several meters without losing resolution.

Early in the project, he noticed that while the camera was shooting, birds would often fly into one or more of the frames. “I liked the results,” he says. “Ultimately, I decided that every series with sky would have birds in it. Some were flying through space in the actual photos, and others were imported later.”

Zaki’s images have caught the eye of Tony Hawk, known as the world’s most accomplished skateboarder, a pioneer of the sport and one of its most prominent advocates. When Hawk first saw Zaki’s photographs of the vacant skateparks and skies punctuated by birds in flight, he recalled the “initial idyllic sense of freedom” that first drew him to the skateboard in the 1970s, back when “we wanted to fly.”

Today, Zaki has made a point to return to Egypt with his own children. While there, he learned of the White Desert, famous for its natural, dramatically wind-eroded rock formations. He hopes to photograph it one day, perhaps for a future project. “But my identity is a conglomeration of ideas and values, not a geographical location or ethnic label,” he says.

Back in California, Zaki remains drawn to the skateparks. He doesn’t mention a favorite, but he muses that one day he might like to design one. It would, he says, be one that captures the light of dawn just right.

Other lessons

Palermo’s Palimpsest Roads: A Study in Multicultural Cooperation

Architecture

Art

History

Europe

Define multiculturalism, and explore how different metaphors affect our understanding of diversity.

MC Escher’s “Extra-logical Realities”: Artistic Progression From Architecture to Mathematics

Art

History

Europe

Create a simple tessellation integrating techniques by Dutch artist M. C. Escher that relies on Islamic-inspired patterns.

The Gambia’s Groundnuts: Identifying Problems and Solutions

Environmental Studies

Anthropology

West Africa

Identify the challenges facing growers of the Gambia’s most-important product—the peanut.