2016 Calendar: Mosaics

- Arts

- History

Introductions by Hamdan Taha, Donald Whitcomb and Paul Lunde

Video by George Azar / The Department of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage of Palestine

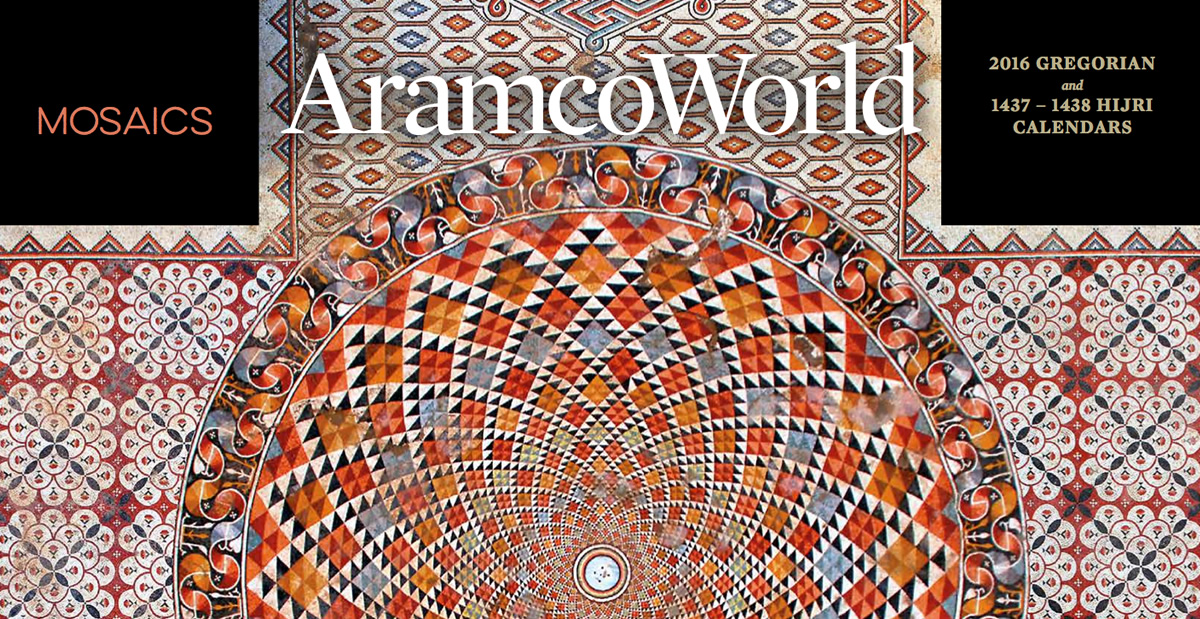

The Mosaics of Khirbat al-Mafjar

A few kilometers north of Jericho, at more than 12,000 years old one of the oldest cities in the world, lie the ruins of a palace with the largest and most artistically accomplished mosaic floor to survive from the ancient world. Composed of 38 intricate panels covering a space over 30 by 30 meters square, the mosaics of the audience hall and bath at Khirbat al-Mafjar (“Ruins of Flowing Waters”; also called “Qasr Hisham” or “Hisham’s Palace”) are masterpieces of early Islamic artistic design.

Dating from the first half of the eighth century, the time of the Umayyad caliphate, about a century after the death of the Prophet Muhammad, the patterns are mostly abstract, but a few use pictorial elements. Drawing from both Byzantine and Sasanian (Persian) traditions, the artists at Khirbat al-Mafjar created a new, exuberant esthetic of intricate geometric and floral motifs. Many are based on infinitely repeatable patterns, a technique that later came to be characteristic of geometric art across the Islamic world; others are based on textile arts and fresco painting.

Until recently, few of these patterns had been published. In 2010 the Palestinian Department of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage uncovered, cleaned and assessed the state of conservation of these mosaics. The floor was comprehensively photographed for the first time. A small museum opened last year, in partnership with the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute.

The ruins at Khirbat al-Mafjar were discovered in 1894 and first excavated in the 1930s and ’40s by the Palestinian Department of Antiquities under Dimitri Baramki and Robert Hamilton. Baramki identified the patron of the site as Umayyad Caliph Hisham ibn ‘Abd al-Malik, who ruled from 724 until 743 ce. This elaborate complex stood for only a few years, however, until the audience hall and bath were largely ruined by an earthquake in 131 ah (748 or 749 ce). In the 1950s and ’60s, further archeological work and some restoration were carried out under Jordanian rule, but the site was abandoned under Israeli occupation from 1967 to 1994. Beginning in 1996 the Palestinian Department of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage revived conservation and archeological efforts.

In addition to the audience hall, Khirbat al-Mafjar included within its 60-hectare complex a large, two-story palace, a multi-room bath, a mosque, a monumental fountain, a perimeter wall and residences. It served as an occasional winter residence for the caliph, and it was part of an array of such palaces (qusur) throughout Syria, Jordan and Palestine that served variously as caravan stations, royal or elite residences, trading posts and security outposts. Like Khirbat al-Mafjar, many developed irrigation systems that allowed them to continue as agricultural estates.

Among its ruins, the audience hall and bath of Khirbat al-Mafjar is the best-preserved and the most striking monument. The exterior walls have 11 semicircular mosaic-tiled apses (or exedra); these half-domed structures echo the interior’s larger and higher domes supported by 16 massive piers. This structure is unique for late Byzantine and early Islamic architecture. The walls and apses were richly covered with carved stone and stucco panels—the earliest known use of stucco in the region—and there may well have been panels of glass mosaics as well.

While the earliest examples of mosaics found in the Jericho region date to the Hellenistic, early Roman and Byzantine periods, the art of mosaic flourished particularly during the Umayyad period. Some of the finest Umayyad wall mosaics, sometimes made of glass tesserae, survive in the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and the Great Mosque in Damascus. Khirbat al-Mafjar shows that the mosaic tradition continued with white mosaic paving into the subsequent Abbasid and Fatimid periods.

The entire floor of the audience hall is paved with colored mosaics. The carpets—as the floor panels are called—divide the hall into circular and rectangular spaces that appear to reflect the architectural superstructure, especially the majestic circular carpet under the central dome. It is likely that the hall served several purposes, from an audience or reception area (majlis) to a room for social events, including musical performances, to an extravagant frigidarium, or cool room, attached to the smaller heated rooms of the bath along its north wall.

Although many Umayyad mosaics are now known in the region, none surpass the mastery of art and craft at Khirbat al-Mafjar. Here, brilliant colors were woven into common motifs to fuse into a new fashion, one that was complemented by no-less-intricate wall coverings of colored stone and stucco carvings in paneled surfaces, columns and other architectural elements; above, there is evidence of painted frescos on upper floors.

When photography, film and conservation studies of the floor were completed, the mosaics were covered with Geotextile and sand for conservation until a permanent, protective shelter can be built over them. Meanwhile, excavations and research continue at other places in the Khirbat al-Mafjar complex. It is hoped that with suitable protection and conservation, the mosaics may one day be uncovered for public viewing, making Khirbat al-Mafjar a prime destination for tourists and historians.

www.jerichomafjarproject.org

To request a free 9”x12” wall calendar, email [email protected], subject line “Calendar”. Be sure to include your full, correct postal mailing address. Calendars are available while our supply lasts. Requests from the USA will be sent by first class mail; all other requests will be sent by airmail. Multiple copy requests (i.e., for a group of classrooms, etc.): Tell us how you plan to use them, and we will be pleased to send them to you, as long as our supply holds out.

January

Rabi` i 1437–rabi` ii

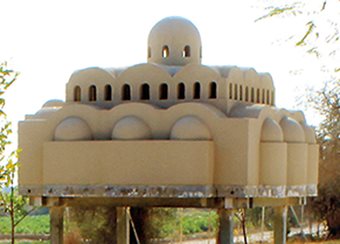

This speculative model of the audience hall shows a clerestory that would have admitted light. There are no contemporary depictions or descriptions of the hall, which was built in the first half of the eighth century and ruined soon afterward by an earthquake in 748 or 749 ce.

Above: This semicircular apse on the east end of the audience hall’s north wall measures about 4½ meters in diameter—the same as the hall’s 10 other apses, which together present one of the hall’s most distinctive architectural features. Each apse is tiled in a unique mosaic pattern: Here, a simple, flat floral pattern, bordered with multicolored diamonds, appears kin to Palestinian textile embroidery motifs that endure today. In front of the apse, the tightly interwoven, curvilinear “runner” uses multiple colors to give the elements in its pattern shape and depth. Along the partially restored back wall, six niches were likely filled with statuary; six of the 10 other apses show similar niches.

February

Rabi` ii–Jumada i

The full design of Panel 8 is shown here edged by its four surrounding panels.

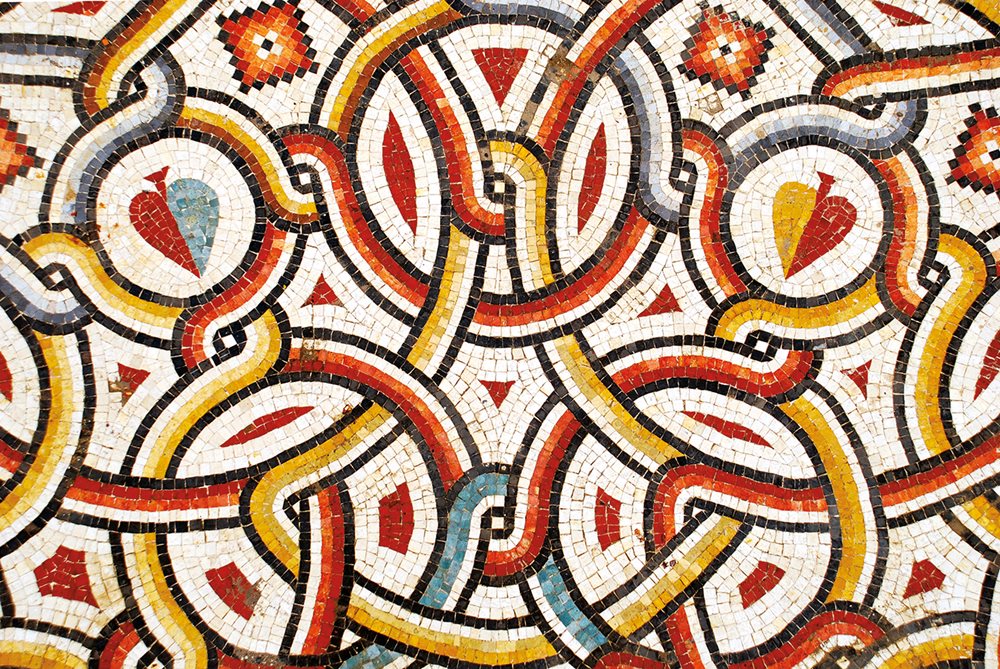

Above: Interaction among smooth curves, static squares, hub-like circles and lines that intertwine among them like thorny vines gives this detail of floor Panel 8, in the west-central part of the hall, an almost living tension. The intricacy of this and other patterns in the hall pushed the boundaries of the mosaic artist’s ability to render complex symmetry with precision; as a result, the slight deviations from mathematical perfection tend to reinforce the organic effect.

March

Jumada i–Jumada ii

This wider view of Apse v shows its relationship to the axial nave, top left. Its original back wall would have been much higher and surmounted, like the others, with a half dome.

Above: Facing east to what was once a grand entryway some 30 meters at the other end of the audience hall’s main axial nave, the design of what has been designated Apse v is the most complex and visually prominent of the 11 apse mosaics. It shows one of only two purely representational images in the hall’s mosaic floor: a central panel with a sprout, ethrog (citron) and knife—a motif common at the time also in Christian and Jewish structures. The radial, basket-like motif, shown here in the foreground, visually links the apse to the much larger, central basket motif under the main dome.

April

Jumada ii–Rajab

This wider view of Apse v shows its relationship to the axial nave, top left. Its original back wall would have been much higher and surmounted, like the others, with a half dome.

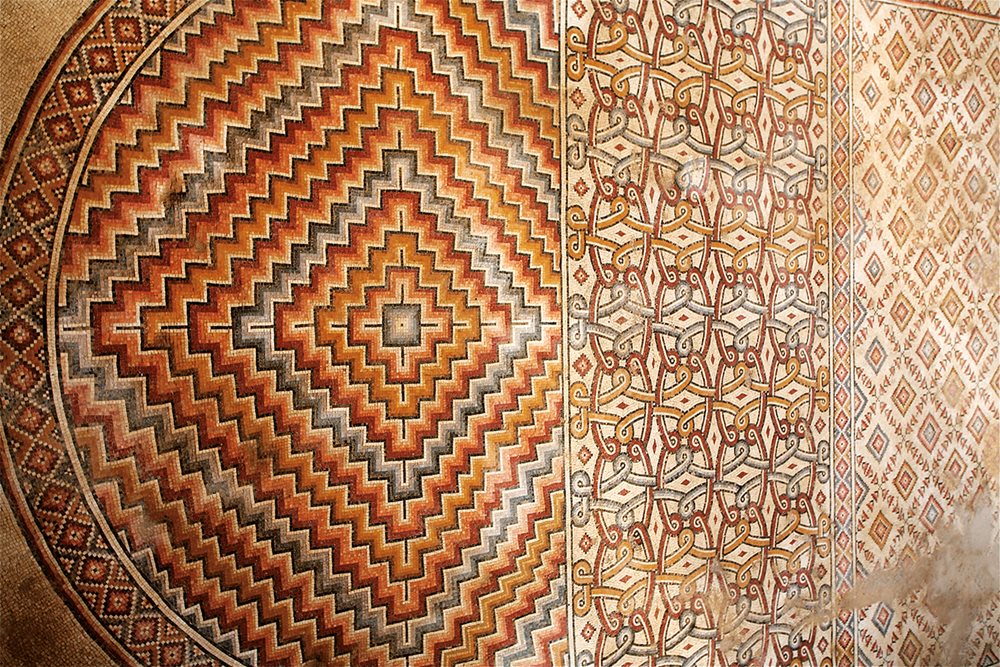

Above: The “basket-weave mosaic” at the center of the hall is one of the most complex and visually hypnotic pattern designs known from the period. Each of its tessera is the same size, and the artisans produced their effect by gradually increasing the number of tesserae in each design element. At the center is a circular marble drain cover.

May

Rajab–Sha`aban

From 1935 to 1948, the first excavations at Khirbat al-Mafjar were carried out by Dimitri Baramki, who is shown here, seated, posed with workers.

Above: In this detail photo, Panel 15, located in the northeast quadrant of the hall, shows a vibrant, four-point pattern of squares, crosses and octagons whose hard lines are softened by thin, flower-like bands. The effect resembles embroidery and other textile patterns; its structure is a four-point pattern of tessellation that would in later centuries be developed in greater complexity in homes, palaces, mosques and madrassahs (schools) throughout the Islamic world.

June

Sha`aban–Ramadan

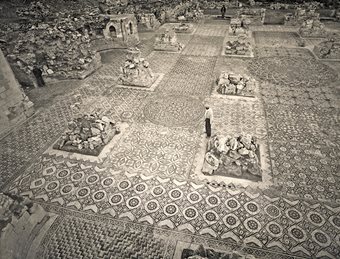

This photo from Baramki’s excavations in the 1930s shows the extent of preservation of the mosaic floor despite the ruin of the building around it. Many of the original stones used for the walls and columns were removed over the centuries for use in other buildings. Recently, the columns have been partially reconstructed in order to help restore a sense of the grandeur of the hall.

Above: This pattern appears on both the east and the west sides of the hall’s center: a design of tessellated squares, each with 24 nearly semicircular petals, each petal inset with a small flower, which produces a bouquet effect. The precision of the geometry is such that the main diagonal lines, which originate at the outer corners and meet at the edge of the circular ribbon band, form a perfect isosceles triangle.

July

Ramadan–Shawwal

Khirbat al-Mafjar was discovered in the modern era in 1894, but its origin and patronage was not known until this fragment of writing, which names Caliph Hisham (724 – 743), was found and translated by archeologist Dimitri Baramki in the 1930s.

Above: Sunlight illuminates color that remains vivid in the tesserae that create this sharply zigzag pattern in Apse vii. Each mosaic piece, or tessera, measures between 13 and 16 millimeters, and most are cuboid in shape. Binding and setting the mosaic floor originally was an underlayer of compacted limestone mortar that itself lay on top of nearly a meter of three further foundation layers of ash, lime, pebbles, sand and earth mixed with rubble and shards.

August

Shawwal–Dhu al-Qa`dah

A ribbon band echoes the more complex band around the hall’s central mosaic; the panel’s central, eight-pointed star with surrounding chevrons presages wood and tile patterns of later Islamic designs.

Above: Three rings of tightly interwoven circles comprise the design of circular Panel 3, one of four such circular designs that lie at the centers of the four corner quadrants of the hall. Here, a set of large circles is inset with a ring of smaller circles of two alternating sizes; below it, an inner ring of circles surrounds and grows out of an eight-pointed star visible in the inset.

September

Dhu-al-Qa`dah – Dhu-al-Hijjah

Today, the walls of the diwan have been restored. When it was excavated, as shown in this photo, the room had to be cleared of the rubble of carved plaster that had fallen from the walls and ceiling. This photo also shows the diwan’s inner, apsidial platform, with the Tree of Life motif, which appears in full in this calendar in December.

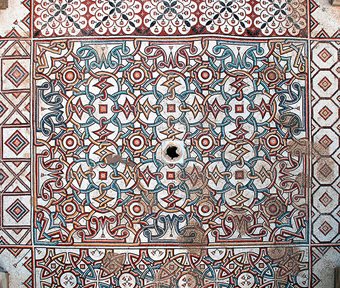

Above: One of the best-preserved mosaics lies in the diwan, a small sitting room that was entered on the northwest corner of the hall. Its mosaic design is clearly intended to resemble, if not imitate, a carpet—it even has tassels on the corners. Its diamond-pattern field is bordered by inner and outer decorative bands, much as a carpet would be; the raised seats show a further mosaic band.

October

Dhu-al-Hijjah–Muharram 1438

In addition to the unique shells, Panel 5 has typical entwined circles in the center, but the outer portion has a unique pattern based on squares with a single rope and leaves.

Above: A corner detail of the circular medallion in Panel 5, in the southeast corner, shows its best-preserved section. The scalloped shell pattern is unique among the hall’s designs, and unusual also for showing seven elements rather than four, six or a multiple of those numbers.

November

Safar–Rabi` i

Above: One of the most visually striking of all the apse panels is the electrically high-contrast, four-point pattern of Apse viii . Its seemingly premature ending, at the edge of the interwoven pattern of the floor runner mosaic of Panel 29, which adjoins on its other side the textile-like pattern of Panel 27, highlights the eclecticism of the hall’s mosaic art.

December

Rabi` i–Rabi` ii

The ruins of the audience hall are marked by the partially restored columns visible to the left. Although the mosaics were covered for conservation until a permanent, protective shelter can be built over them, excavations, research and conservation continue at other locations amid the palace, mosques, baths, residences and agricultural estate at Khirbat al-Mafjar.

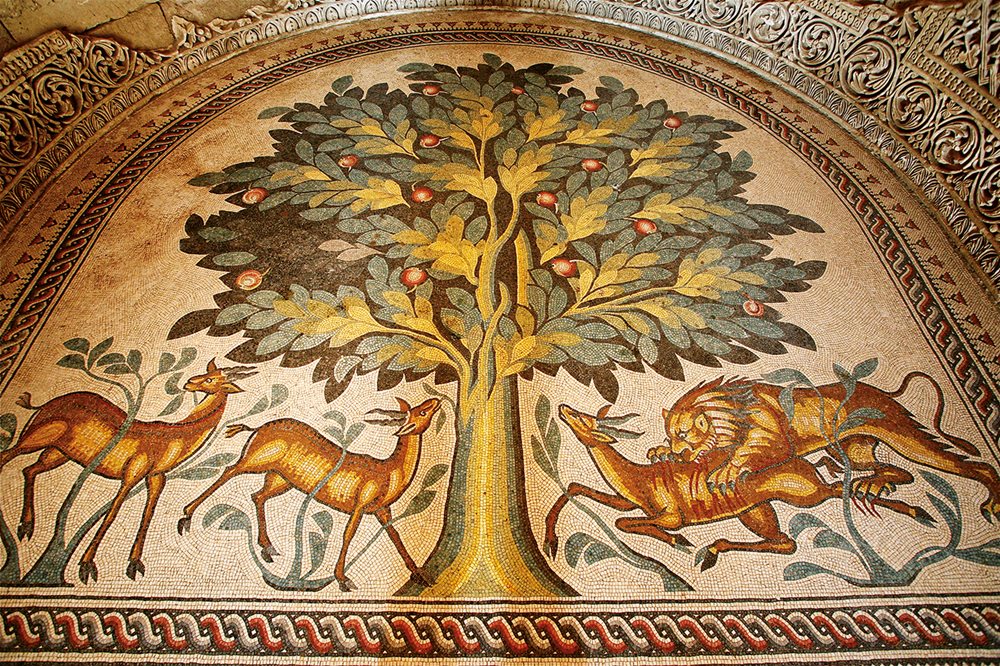

Above: Although the audience hall mosaics can be interpreted both as echoes of the past and harbingers of the geometric patterns that in later centuries became associated with the highest expressions of art in Islamic lands, one of the finest mosaics at Khirbat al-Mafjar is pictorial: The Tree of Life, which lies in an apse at the focus of the diwan. The motif harkens back to Roman and Byzantine examples, but was here executed with unique mastery. It shows a lushly fruited tree, under which two gazelles graze peacefully—a common motif in mosaics and frescoes throughout the region and southwest into Egypt—while on the right, a lion attacks a fleeing gazelle. “The composition and technical perfection of this mosaic, its range of coloring, and the intensity of its scene make this carpet the chief wonder of the arts at Khibat al-Mafjar,” wrote Taha and Whitcomb.

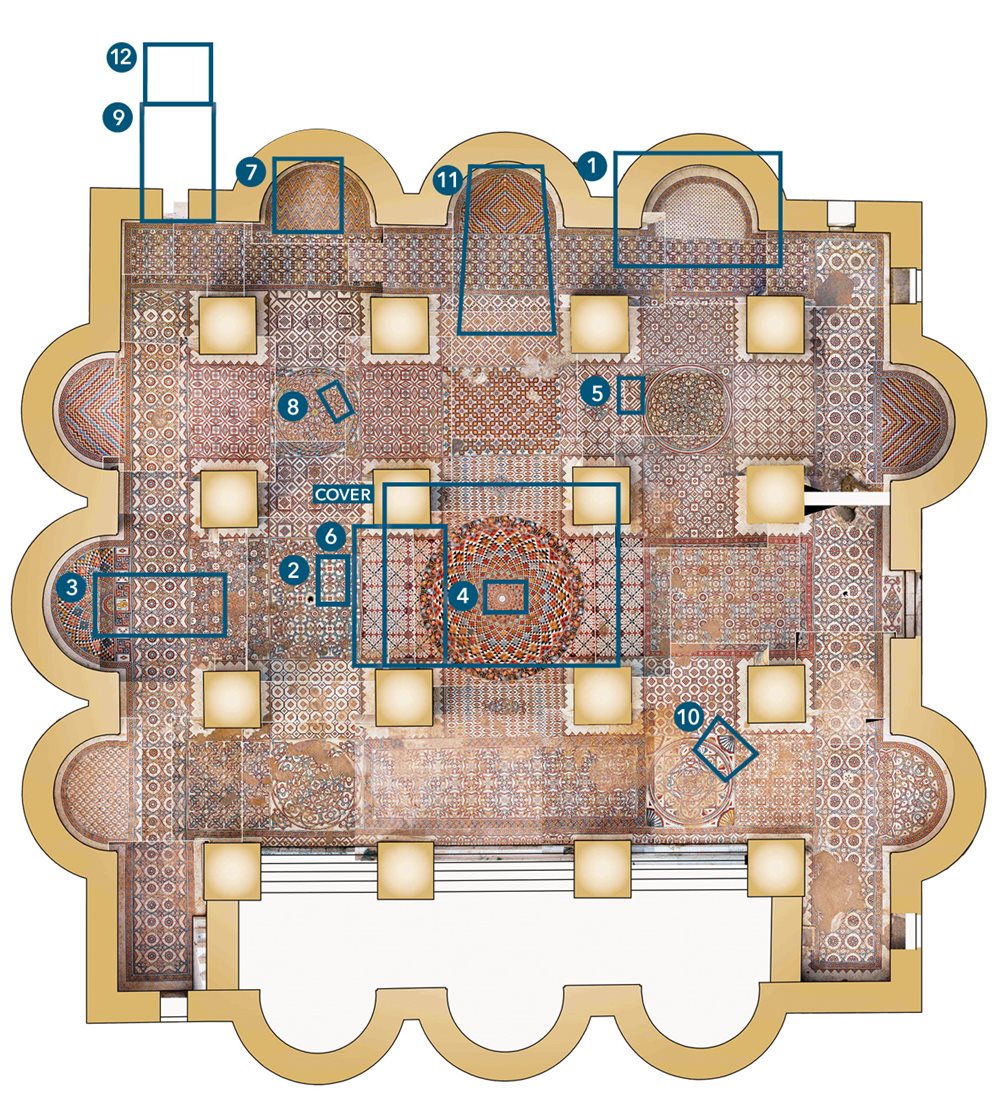

This composite floor plan offers a visual guide to the largest preserved mosaic floor from the ancient world: The early eighth-century mosaics of the audience hall at Khirbat al-Mafjar near Jericho, Palestine. Beginning with number 1 for January, each numbered box shows the location of the photograph for its corresponding Gregorian month.

About the Author

Donald Whitcomb

Donald Whitcomb is an archeologist at the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, where he specializes in Islamic archeology and the Early Islamic city. Together they co-directed the joint Palestinian-American excavation at Khirbat al-Mafjar from 2010 to 2014.Hamdan Taha

Researcher and author Hamdan Taha is a former director-general of the Department of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage in Palestine who has also directed and co-directed a series of excavations and rehabilitation projects.Paul Lunde

The late Paul Lunde authored more than 60 articles for AramcoWorld. He was a senior research associate with the Civilizations in Contact Project at Cambridge University and also co-author, with Caroline Stone, of Ibn Fadlan and the Land of Darkness: Arab Travellers in the Far North (Penguin, 2012).

You may also be interested in...

Celebrating 75 Years of Connection Stories and Culture

Arts

History

Since its origins in 1949 as a company newsletter for Aramco, AramcoWorld has evolved to focus on global cultural bridge-building across the Arab and Muslim world and beyond.

Revival Looms

Arts

In Georgia Borchalo rugs are making a tentative comeback amid growing recognition of the uniqueness of ethnic Azerbaijani weaving. There’s hope that this tradition can be saved.

Nakshi Kantha: Tradition and Identity in Every Stitch

Arts

History

A traditional form of quilting in Bangladesh in which women embroider family history, love and memory into the fabric is blanketing markets locally and beyond.