Are Georgia's Borchalo Carpets Making a Comeback?

- Arts

- Textiles

12

Written by Robin Forestier-Walker, Photographed by Pearly Jacob

Zemfira Kajarova was only 16 when she came to the ethnic Azerbaijani village of Kosalar in 1976, in what was then the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic. Despite hailing from a nearby town and being ethnic Azerbaijani herself, Kajarova was considered an outsider. She soon discovered a community that took great pride in its rug-weaving tradition, brought here centuries ago by its Turkic Muslim forebears.

Kajarova had to learn a new skill. “My mother-in-law taught me how to weave,” she says, smiling at the recollection. “This was how we bonded.”

Today weaving still bonds the older women of Kosalar who, like their ancestors before them, sit together at the loom in humble homesteads and produce Borchalo (or Borchaly) rugs recognized by collectors for their quality and design.

The carpets are handwoven with a luxuriously soft but thick pile, of wool dyed in a variety of natural colors extracted from plants that include juniper, walnut and madder. Their patterns use simple geometric symbols like the tree of life and medallions known as guls.

Despite antique examples fetching high prices at premier auction houses such as Christie’s, contemporary Borchalo rug-weaving faces a bleak future. All of the active weavers in the community are older than 50. Unless more young women learn the craft, it risks disappearing forever. “I’m afraid that this heritage will die,” says Kajarova. “The elderly can’t weave anymore, and the young people don’t want to take this responsibility. They say it’s difficult work.”

Regardless of the challenges, there is a growing recognition of the uniqueness of ethnic Azerbaijani rug-weaving in Georgia, and with new efforts on the way, there is hope that this tradition can be saved.

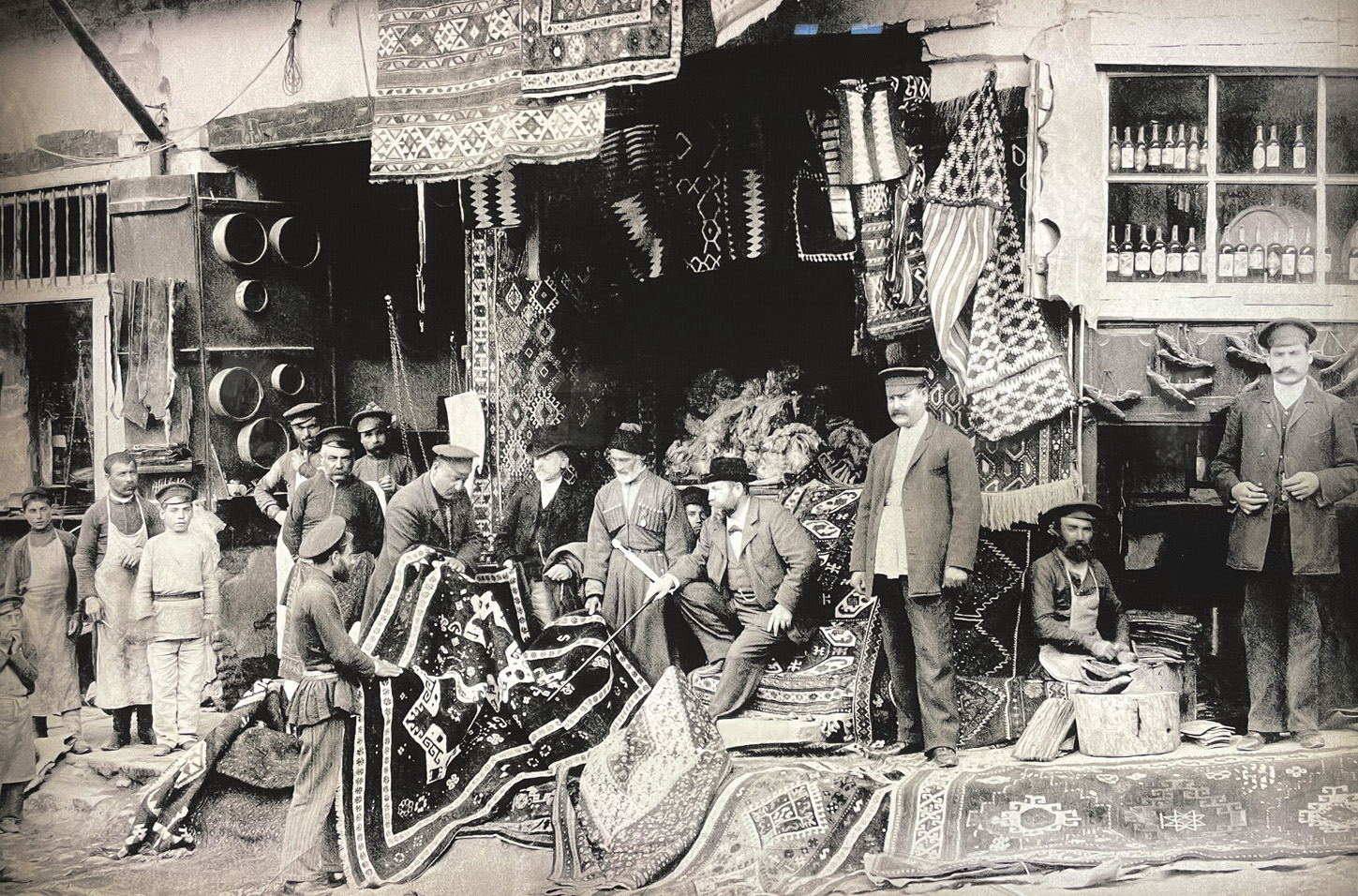

Rug sellers in the early 1900s in Tiflis (modern-day Tbilisi), Georgia.

Tradition’s history

Kosalar sits on a grassy plain in southern Georgia, at the foothills of a volcanic mountain range stretching into modern-day Armenia and Türkiye. It is close to the town of Marneuli, formerly known as Borchalo, from which the rugs take their name.

Kosalar’s community forms part of a larger Azerbaijani minority in Georgia of almost 250,000 people. At the time of Georgia’s last census in 2014, ethnic Azerbaijanis in Georgia comprised 6% of the total population. Some sources suggest that number has increased.

Irina Koshoridze, chief curator of oriental collections at the Georgian National Museum, also believes that the Borchalo weavers are direct descendants of nomadic pastoralists from northern Iran who came to what is present-day Georgia during the Safavid dynasty.

“According to legends and historical sources, they were settled by Shah Abaz the Great in the 17th century,’’ says Koshoridze. “The name ‘Borchalo’ comes from the name of a nomadic Turkmen tribe, who originally lived in the Sulduz region of Iranian Azerbaijan, distinguished by their bravery and fighting skills.”

The origins of the Borchalo weavers are still open to debate.

Other historians claim nomadic Turkic tribes brought their culture to the Caucasus as early as the fourth century CE. “They moved from Central Asia. We’re talking about a huge territory and symbols from this huge community with different ethnicities,” says Shirin Melikova, former director of the Azerbaijan National Carpet Museum. “If you research patterns and ornaments of all these communities, from Siberia, Altai, Uyghurs, from Central Asia to the Caucasus, you will see this one big picture,” she adds.

The region eventually fell into the hands of the Russian Empire and later became part of the Soviet Union. When the Russian Empire created a Caucasian Handicraft Committee in 1899, it aimed to develop weaving centers across the Caucasus to produce rugs for an international market. Steamboat and rail opened the regional rug trade to the wider world, connecting the bazaars of Tiflis (as the capital, Tbilisi, was then known) to tastemakers in New York and Paris.

According to Koshoridze, Borchalo and Karachop rugs (another regional variation) benefited not only from new looms and designs introduced during the Tsarist period but also from preserving their distinctiveness by a later quirk of fate.

Soviet planners chose to develop a carpet-weaving industry in established weaving centers around Baku, in Soviet Azerbaijan. Karachop and Borchalo, which were located in the neighboring Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic, were excluded. “They kept their traditions because they never worked for an international market during the Soviet period, and this is why they were so special,” Koshoridze says.

When Western dealers “discovered” antique Borchalo rugs in the 1990s following the breakup of the Soviet Union, “they were seen as something new, with strong, bold and very individual designs,” says Koshoridze.

By then, though, most looms had fallen silent. Once, the women had woven their bridal dowries from their wool or sold the rugs to merchants in Tbilisi. But the 1990s were desperate times. The wool industry was broken, and cheap machine-produced rugs left the weavers with little incentive to continue their work.

Those who did continue used any materials they could find, including artificial fibers and chemical dyes. Idiosyncratic prayer rugs of vivid colors were woven for local mosques. They possessed their own folk charm, but the 19th-century artistry had been abandoned. “No one supported these women, and nobody bought these carpets like they used to; that’s why many weavers stopped this tradition,” says Melikova.

Steamboat and rail opened the regional rug trade to the wider world, connecting Georgian bazaars to New York and Paris.

The mosque is the central attraction in Kosalar, one of the few villages where the ancient craft of Borchalo rug-weaving has been revived thanks to social enterprise reWoven. The very act of weaving in the southern Georgian community harks back to a slower pace of life uncommon in today’s world.

Left: Outside weaver Elmira Ceferova’s house, men get ready to drive sheep to pasture. Right: Elmira Ceferova, left, and Zemfira Kajarova, right, work together to stretch the horizontal white yarn, called warp, on a loom in preparation to start weaving a rug for social enterprise reWoven at Ceferova’s house in Kosalar.

Revival

While rug-making has been part of Azerbaijani traditions for centuries, the communities faced losing the craft in recent years.

Then a young American Christian missionary saw an opportunity to jump-start the looms of Kosalar again.

Ryan Smith fell in love with the weaving culture when he lived in Azerbaijan in the early 2000s.

As he traveled in the region and met people, he had a vision: Create a market for new Borchalo rugs made with the luxury and motifs of the finest antiques.

A fluent speaker of Azerbaijani, Smith found buyers, sourced quality wool and natural dyes, and persuaded retired weavers to reproduce the work of their grandmothers. In 2014 he founded a local nonprofit organization, reWoven, to restore traditional rug-making.

Ryan, Melikova says, inspired a revival. “This was a big part of his life. It wasn’t just a question of business. He did a lot to revive this tradition in Georgia. And he started to work with the local women.”

reWoven ships about 30 rugs a year. Larger ones cost up to US $3,000, and the weavers receive a competitive price for their work. All the remaining revenue funds community projects.

“The margins are really thin,” says William Dunbar, “but we have been able to increase the cost per square meter, and we will continue to do so.” Dunbar took over reWoven’s management after Smith’s tragic death in 2018. His motivation is to continue Smith’s work and sustain the tradition.

Some of the looms are 100 years old and may even have made rugs that command a $125,000 price tag at Sotheby’s and Christie’s, Dunbar notes. “It’s super important for the communities in which they are woven to understand that people value this incredible cultural production,” he says.

“It’s super important for the communities in which [the rugs] are woven to understand that people value this incredible cultural production.”

Left: Older hands teach younger hands to weave at The Tea House in Marneuli. Right: 15-year-old Amina Mehdova, left, and 14-year-old Maya Ziadalieva are among the youngest students learning to weave at the center.

“We understand each other, we help each other when we fall behind, and we weave together.”

A new generation

The lack of weavers makes it challenging to keep up with demand for rugs. A solution might not be far off. The Tea House in Marneuli, an education center, provides cultural classes for young people.

Fourteen-year-old Maia Ziadalieva recently became curious about weaving while waiting for her brother to finish his dance classes, though she knew nothing about the tradition before trying it. “There is a silence here, and I feel relaxed while weaving,” Maia says. “I don’t know what will happen in the future, but I do like the process, and I think others can too. I would like to teach it.”

Twelve students are currently learning to weave. However, Tea House director Emin Akhmedov has a bolder vision: establishing weaving centers in villages where the culture is still alive. “We can see people ready to spread the knowledge,” says Akhmedov. “And we need young people’s knowledge in terms of marketing or branding to see it as a business.”

“We’re never going to be a big business,” says Dunbar. reWoven is instead focused on artistic preservation, sustaining a cottage industry rather than scaling up, though he sees opportunities for “up-skilling” the community.

A reWoven finishing station will soon complete the final cleaning and softening of rugs in Georgia. Currently, the process is outsourced to Azerbaijan. Dunbar explains that the yarn is sourced in Iran and then dyed in Baku, but that, too, could change.

“These carpets were not made with imported yarn 100 years ago. We’ve got a million sheep in Georgia; the wool value chain has collapsed. We can use Georgian wool, and we can pay the shepherds a little bit extra. We can get it dyed here.”

The Tea House is the only place that offers formal classes in Borchalo rug-weaving, the craft traditionally passed down from mother to daughter. With youth at the loom, the artform has a chance of being kept alive.

In Kosalar, the women bake their loaves of flatbread together in a small bakery, a shed with a stone oven. The fire blazes with thorny branches of brushwood, and the steaming flatbreads are filled with a local spinach variety. Their shared labor, at the loom or in the fields, ensures a continuity of tradition.

Their exquisite rugs, which can trace their lineage back to the Safavid dynasty, have evolved and adapted. They are guided both by their own aesthetic and by international demand. And though the future is still uncertain, Borchalo rugs’s existence no longer hangs by a thread.

About the Author

Pearly Jacob

Pearly Jacob is a multimedia journalist, photographer and filmmaker. She has traveled widely across Central and South Asia and Western Europe by bicycle, and has produced stories on a wide variety of environmental, sociocultural and human-interest topics for clients ranging from Al Jazeera, BBC, DW, National Geographic, Voice of America and others.

Robin Forestier-Walker

Robin Forestier-Walker is a British freelance journalist and filmmaker based in Tbilisi, Georgia. He has written and reported extensively for the Al Jazeera Network in the South Caucasus, Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

You may also be interested in...

Artists Answer COVID-19

Arts

Amid this year’s travel bans, museum and gallery closures, lockdowns, quarantines, and social distancing, visual artists are responding with fresh imagery and creative collaborations across new platforms to articulate this moment and carry culture forward into the next.

On Their Own Terms

Arts

The United Kingdom is experiencing a surge in demand for contemporary art of African origin. For artists of the African diaspora, the UK represents a new arena in which to showcase their messages through unique techniques and mediums. Interest in their work follows mounting pressure on museums, universities and other institutions to “decolonize” their curricula and collections.

Nakshi Kantha: Tradition and Identity in Every Stitch

Arts

History

A traditional form of quilting in Bangladesh in which women embroider family history, love and memory into the fabric is blanketing markets locally and beyond.