For centuries across much of the globe, it has been the custom for women to bring with them on marriage not only money, but also linen, personal clothes and jewelry.

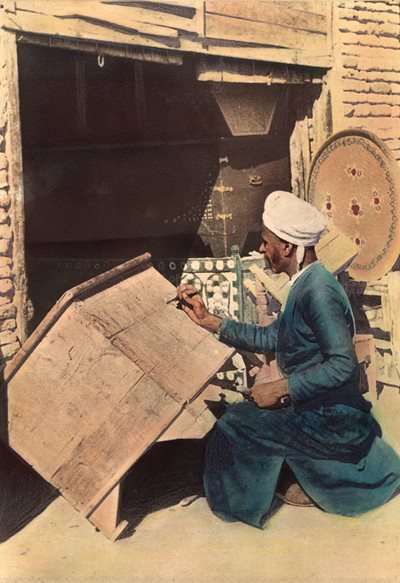

Shown working near the Euphrates River in Iraq in 1922 in this hand-colored photo, a craftsman is decorating a wooden chest. Although demand today is greatly diminished, the tradition of making chests continues, from ornate, handcrafted chests to mass-produced metal boxes.

Almost all but the most impoverished women would bring with them the basics needed to set up house. Giving money to enable girls to marry has been a charitable act in much of the Muslim as well as the Christian worlds, and, indeed, the custom of Santa Claus and Christmas gift-giving is thought to have originated with St. Nicholas of Myra (modern Demre in Turkey), who secretly provided money to dowry-less girls.

The value and significance of dowry items have varied greatly, from the sheets and household linen in the bottom drawer traditional in the uk to the “hope chests” of North America, to elaborate trousseaux of jewels, embroidery and weavings intended to show off the family’s wealth or the young woman’s skill.

In many parts of the world, gifts passed to a newly formed household for the new bride—the dowry, whether it may be called that or not—often set a course for a marriage, and sometimes affect its success. Often in times past—and in some places still today—these goods were packed into a chest, traditionally made of wood and typically decorated as richly as means would allow, the better to show it off as a status symbol when the bride arrived at her new home. Across the Middle East, where houses were traditionally sparsely furnished, such a dowry chest would often be placed in the woman’s area, where it could quietly continue to announce its status and serve as an item of practical furniture.

The basic form of most of these chests is large and rectangular. Usually they are flat on top (though some are curved), so that they could be used as a bench or small table; sometimes they were built with drawers below the main compartment and, often, there was a smaller compartment inside the lid for holding valuables.

It can be difficult, even impossible, to determine whether a given chest was in fact intended to serve for a dowry or whether it was commissioned for some other purpose. However, it is probable that the most richly decorated pieces were marriage chests, particularly those decorated with good luck symbols and signs of red paint—the color of celebration, fertility and blood.

This ivory casket, shown here about 2/3 life-sized, was carved in about 961 ce near Córdoba for the daughter of Abd al-Rahman iii.

Along with one or more large chests, the young bride would often bring a smaller box for her jewelry and makeup. Some of the earliest surviving examples of these are also some of the finest known: for example, the ivory one from Madinat al-Zahra near Córdoba in al-Andalus, a modest-sized box that belonged to the daughter of Abd al-Rahman iii and is dated to shortly after 961 ce, is beautifully and richly carved. Around the edge of the cover, the Arabic inscription translates: “In the Name of God, this is what was made for the Noble Daughter, daughter of ‘Abd al-Rahman, may God’s mercy and goodwill be upon him.”

Small jewel boxes to accompany the bride continued to be popular well into the 20th century. A hardwood type with a “house roof” lid made of four flat, sloping slabs of wood with decorative brass hinges and locks was widely exported from India; another model, often made in Damascus using camel bone or mother-of-pearl inlay, has historically been favored by wealthy Bedouin. There are also the chests from the Iran-Pakistan border region called makran with heavy brass decoration, which also seem to have been made for export, especially to East Africa.

Red paint under brass studs and appliqué plates of this 19th-century “Zanzibar” chest indicates that it likely was used for a dowry.

Large chests for dowries and other uses of course also existed, but relatively few have survived. There are numerous mentions of them in Arabic literature, and they also appear among documents in the Cairo Genizah. (See sidebar) The 14th-century Mamluk-era historian Al-Maqrizi describes the chests available at the specialized market in Cairo. Some combined chest and taht, or a daybed (like those still being made in Java during the early 20th century), while others, also called muqaddimah, were made of leather or sometimes bamboo, and they seem to have been in use as cosmetics boxes.

Decoration on dowry chests varies from region to region, depending on local taste and available materials. Sheila Unwin, author of The Arab Chest, concedes it is hard to date many chests or even give them a provenance since little appears to have been written about them before the arrival of Europeans. Generically, they are known by a number of names: mandoos, sanduq and safat are three of the most common. More specific types are often referred to by a place name—Omani, Kuwaiti, Bahraini, Zanzibari, etc.—but these often refer to where they were acquired, rather than where they were made.

From the Dir Valley in northern Pakistan, this chest is carved from Himalayan cedar. Its pieces are joined, not nailed. Its legs are part of its design, and their rise above the lid is characteristic of the region’s style. The wooden tab on the right is used to pull open a front panel.

Most of the older chests used to come from India, thanks to its abundance of hardwoods, teak and rosewood especially. Scholars have argued that the Portuguese sailor’s chest—generally a plain strongbox with brass corners, hinges and a lock that served like the modern military footlocker— inspired the general idea, but the decoration was a purely local innovation. The more elaborate of the Indian chests might have had drawers at the bottom (generally three) and could be placed on a stand to protect them from damp and insects.

According to Unwin, chests imported from India could be classified into four main types. The top three were the most striking and sought after: Surat, Bombay and Shirazi. This last was not made in Shiraz (now in Iran), but found in the areas of Persian influence. All were built in long-lasting teak or other hardwoods, and they were decorated with designs of brass studs and sometimes brass plates cut into geometrical or scrolling appliqués, which became increasingly elaborate in the course of time.

A late 19th- to early 20th-century Zanzibar chest ornamented with engraved copper, alloy medallions and embedded studs.

Modern alternatives to the traditional wooden dowry chest are often mass-produced and made of galvanized steel painted in enamel.

Some of the most expensive were lined with camphor or sandalwood that protected the contents against insects and gave them a delicious scent. These chests sometimes have traces of red paint, indicating their use for holding the dowry, and they were often set on separate wooden feet painted in stripes. The carpentry of the finer chests cleverly inserts secret drawers and tuck-away compartments to hide special treasures. This is the style of chests that came to be copied around the eastern Arabian Peninsula, especially in Oman.

The Shirazi chests were particularly elaborate, as Unwin describes, with “sparse heavy cast brass plating ... [and] diamond-shaped disks.” One of the rare dated examples belonged to Sayyida Salme, the daughter of the early 19th-century Omani sultan of Zanzibar Said bin Sultan al-Said, and it is now in the Sultan’s palace. Salme married a German merchant in 1866 and fled Zanzibar, which gives a probable date for the chest. Married as Emily Ruete, her autobiography, Memoirs of an Arabian Princess, published n 1907, sheds unique light on the period.

Another less common type came from Malabar, in southwest India. The “Malabar chest” is carved, often in mahogany, rosewood, shisham or other hardwoods, and a favorite pattern uses a round central vase—lota—with trails of flowers and fruit, sometimes grapes or pomegranates. The design shows Portuguese influence, although that particular motif suggests fertility and good luck from Europe into East Asia and it is particularly appropriate for weddings.

The mixture of cultural elements is not limited to Portugal, India and the Arab world. The traditional way of securing the chest was with a hasp, often very decorative, and padlock. While locks and keys were a Portuguese and Dutch innovation, another locking device, one that uses three rings and a padlock, came from China, as did the design of some of the handles and hinges.

Other evidence of cultural tastes and traditions appears in the ornamentation. Designs of metal wire with inlays of mother-of-pearl or camel bone, for example, originated in Egypt-Syria during the ninth and 10th centuries. This style was typically produced for the well-to-do urban classes, while most of the rest of the population used plain or carved chests. Complex woodworking crafts such as intarsia and marquetry were popular throughout the Ottoman territory, and in the 19th century such chests were exported to Europe, especially to France. Chests were commissioned, as were sets of furniture in the European style, for weddings. The patterns tended to be extremely elaborate, sometimes with the entire chest covered in mother-of-pearl and lined with scented wood or silk brocade or velvet.

The manufacture of these types of inlay was a specialty of Damascus, although by the late 20th century there were far fewer craftsmen working than in the past, with commissions arriving largely from the Arabian Peninsula. Again, changing traditions, fashions and economies have led to very few traditional dowry chests being made, and instead, chests of drawers, cupboards and other more modern designs are favored.

In North Africa, fine hardwood is difficult to come by, and as a result, dowry chests are generally painted, as soft woods such as pine or palm do not lend themselves well to delicate carving. Families of modest means might have a plain coffer decorated with a simple pattern, such as the row of arches common all across the Muslim world, in two or three colors. Damages to the lids, including nicks and burns, indicate that many chests served a variety of purposes besides containing valuables.

Like many chests of softer woods from North Africa, this chest from Djerba, Tunisia, is painted rather than carved.

Wealthy homes would often have much larger chests, some even too tall to sit on or to serve as work benches. Many were elaborately painted, with dark red being a favorite background color and designs often including stylized flowers and plants. One favorite design is a large central roundel with a bowl of fruit or vase of flowers—both universal symbols of celebration and fertility; another shows a pair of doves drinking from a fountain, perhaps copied from early-Christian sarcophagi, which in the 19th century were still to be seen in the countryside, even being used as horse troughs. In Tunisia, fish are a popular motif, sometimes shown swimming in a circle, since fish not only represent fertility, but also are considered to bring good fortune and protection against the evil eye.

This very large, elaborately carved chest, photographed on display in the Azem Palace in Damascus, would have been used by only the wealthy.

Morocco also has its own wider tradition of painted furniture, but here, geometric patterns that often match with the architectural decoration are the norm, and the arched design is particularly popular. Old pieces are rare, but there is a flourishing reproduction industry, although the colors used tend to be brighter than the originals. Traditional Moroccan chests sometimes have curved tops, a detail that is probably the result of Spanish and Portuguese influence, particularly along the coast.

In contrast to North Africa where hardwood was scarce, far to the east, in the Swat Valley of Pakistan, good-quality Himalayan cedar wood was so abundant that it was a prime material for everything that could be made out of it, from buildings to plates and bowls—and of course chests. Carving there is a highly prized skill, and chests form an important part of the furnishings of every house, although once again it is hard to establish which particular ones have been specially made for the dowry.

Many ordinary antique chests show great wear today, such as these on sale in a market in Oman.

Chests from Swat normally stand on quite high legs that continue up above the body of the chest to recall slender minarets. The top and bottom borders of the chests are often worked in a toothed or scalloped pattern. Like the fine chests found in the Arabian Peninsula, they are made with fitted joints rather than nails. The fronts of the chests often have two or more panels, and they normally open with a sliding or hinged door at the front, rather than from the top; the door is closed with a hasp and padlock instead of a key. The carving is generally geometric or with stylized garlands of leaves and flowers—which likely symbolize the sun’s disk—and the usual architectural arches. Some chests have completely different patterns on the two front panels, and some experts have suggested that these distinct designs represent bride and groom, but this is not certain.

It must be added that chests, while very widespread, were by no means a universal tradition for dowry objects throughout all the many Islamic cultures and regions of Islamic influence. For example, baskets, which are cheaper than chests though less durable, are favored in rural Yemen. Many areas of Indonesia have a strong tradition of container-making from a variety of leaves and fibers, and some dowry boxes made this way are worked in different colors and sometimes embellished with cowries. Wealthy Indonesian families would sometimes have chests of the Omani type, imported through their trade connections, or ones of the Dutch colonial type, or yet others showing Chinese influences. Village Java, in particular, produced magnificently carved hardwood chests—grobog—one style of which was designed to double as a daybed; yet again, it is rarely clear which of these were specifically intended for the dowry.

The cultural role of the dowry chest is highlighted in Al Ain, United Arab Emirates, in this public artwork in a traffic roundabout.

Fashions, traditions and social expectations change. In the us, the hope chest has long since given way to the “bridal shower.” Dowries, too, have changed and often disappeared—and so have the chests. Few of the very beautiful and elaborate ones are still being made, or, if they are, it is more for neo-traditional interior decoration than a bridal trousseau. Where they still exist, scarcity of fine wood and skilled craftsmen, and the abundant competition of inexpensive, industrial alternatives have perhaps forever changed the style of the dowry chest. When a dowry chest is still used, it now tends to be a tin or galvanized steel trunk, a footlocker, rather than a artisanal wooden chest. Better than wood against damp and insects, the metal chests are still called sanduq ‘arus, or “wedding box,” and they are still often imported to Arabian Gulf countries from India. But instead of brass studs, carving and marquetry, they are painted with enamel designs that often show mosque domes, reminiscent of the architectural designs on the older chests, although in color, red still tends to predominate.

Dowries of embroidery and weaving may be long out of fashion, but the chests themselves become more and more desirable as they become rarer, social and artisanal artifacts of a bygone era.

You may also be interested in...

At Home in the World: A Conversation with Maryam Hassan

Arts

Growing up in London, at age 13, Maryam Hassan decided she’d move to Chicago one day. The city had glittered in her imagination because she was certain that it bore no resemblance to her hometown.

On the resilience of handicrafts in Bosnia-Herzegovina

Arts

The backstreets of Sarajevo’s old town are alive with the repetitive thud of metalworking. In this European capital, with its contemporary high-rise buildings and modern brands, you can still hear the heartbeat of tradition.

Covering 75 Years of Arts & Culture

Arts

Sharing connections in the arts and cultural heritage is reflected in AramcoWorld's cover stories about architecture, visual arts, photography, music, literature and more.