Mathematics may have been her profession, but now maleeda is one of Nazira Ali’s passions.

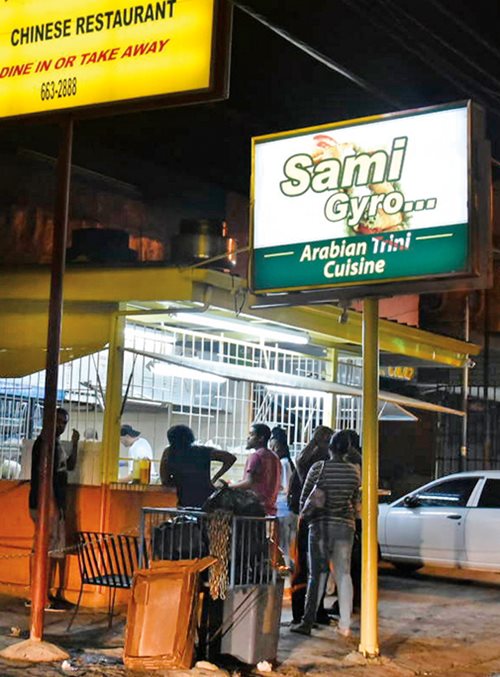

Middle Eastern fast food is the latest culinary arrival to Trinidad, where it has become a new favorite with the late-night crowd. Vendor Zuher Dukhen says that “mostly we serve chicken because that is okay for most everybody—Hindu or Muslim.”

Rolling dough and baking, she makes the traditional sweet to share on Muslim holidays and also to send with pilgrims leaving her native Trinidad for the hajj in Makkah—with the provision they deliver some to her son, who lives there.

Maleeda is a sweetened dough ball made from a soft Indian griddle bread called paratha roti that first came to this Caribbean island in the late 19th century with Afghans, many of whom arrived as indentured servants, as well as with Muslims from India. Ever since then, Trinidadian maleeda has been adapted, like so many of its foods, to local tastes and ingredients such as coconut, cinnamon and clove, which are ubiquitous in Caribbean sweets—the latter two originally hailing from Southeast Asia. Although maleeda is to Muslims a special dessert for Muslims during Ramadan, the month of sunrise-to-sunset fasting, non-Muslim Trinidadians welcome it, too.

Zalayhar Hassanali served as the island nation’s first lady from 1987 to 1997. She is widely credited with the betterment of social relations among Muslims and non-Muslims—an accomplishment in which food and cooking played a part. “When I became First Lady, I served East Indian, Chinese, Creole and Syrian foods at state dinners to demonstrate our nation’s diversity,” she says.

“It’s a usual thing for neighbors to share sweets and foods with each other,” says Ali, now retired and living near Point Lisas, an oil-industry town in the central part of the island. She is part of Trinidad’s Muslim community, which comprises mostly people of African, East Indian, Afghan and Syrian roots. “People will ask for and look forward to sweets like maleeda or sawine—the vermicelli pudding—that we normally make to bring to the mosque.”

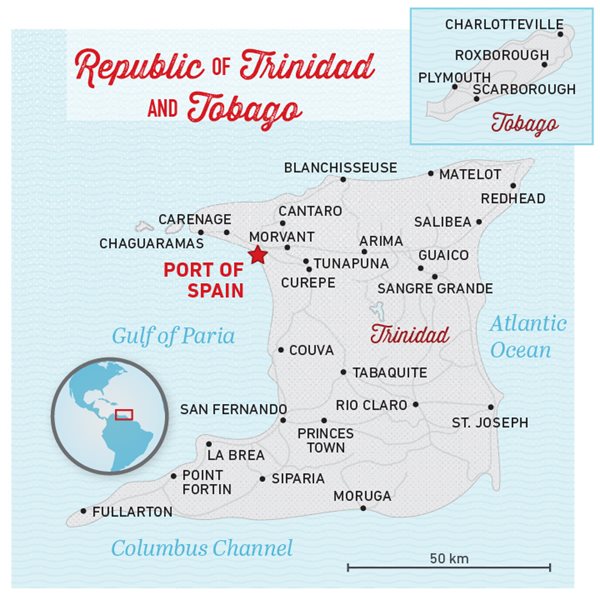

The two-island country of Trinidad and Tobago, the southernmost islands in the Caribbean chain, is a nation of many cultures. Just 13 kilometers off the coast of Venezuela, Trinidad was among the few places Christopher Columbus actually dropped anchor, and it quickly became a prize in the colonial battles for the New World. Initially colonized by Spain, it was taken by France and, for its longest period, England.

The colonial powers brought enslaved Africans here and, later, indentured Chinese and Indians of Buddhist, Hindu and Muslim faiths, all to work on the sugar and cocoa plantations that built Trinidad’s first fortunes. (Today nearly half the island’s economy relies on oil and gas.) Cocoa laborers were recruited also from Venezuela, and, later, refugees from Syria and Lebanon found their way to these shores in an ongoing immigration that began in the late 19th century and continues today.

Spread below mountainous northern Trinidad lies the Caroni plain, and beyond its towns and cities stretch the once-vast plantations of sugar and cocoa that made Trinidad a contested prize among rival Spanish, French and British colonial powers. Each brought enslaved and indentured peoples variously from Africa, Asia and South America, leading to today’s shared palate of tastes that is as varied as the island’s history.

Second to Christianity, Islam is the longest-practiced religion in Trinidad. The first known and, later, most prominent Muslim was Yunas Mohammed Bath, an enslaved West African from the area between the Senegal and Gambia rivers. Literate in Arabic, he arrived in Trinidad around 1805, and he quickly became a leader among fellow enslaved Mandingo (Muslim) Africans.

A decade later Africans who were originally enslaved in Georgia and the Chesapeake region of the us arrived in Trinidad, where they were granted their liberty and some land along the eastern shore as payment for military service to Britain during the War of 1812.

Adam Abboud’s family-owned pastry shop in Port of Spain attracts a loyal clientele that comes for herbs and spices imported from Syria and Lebanon as well as uniquely local family recipes like Adam’s pepper sauce, which he tuned to Trinidadian tastes.

Today eastern Trinidad remains a largely Muslim and mixed-race enclave, bolstered in the mid-19th century by indentured servants hailing from what is now Pakistan and northern India. As with all of the faiths, ethnicities and cultures that make up Trinidad today, it is food that most often provides opportunities for fellowship and understanding.

“Growing up, I remember that it was always the men who would make the paratha roti for big Islamic functions—weddings or holy days. They were the experts, so when anyone had a function—even if they were Hindu or Christian—the Muslim men were called upon as the best paratha roti-makers,” says Ali’s daughter Safiya, an attorney with Caricom, the Caribbean Community Secretariat, which promotes policy and development among 15 Caribbean nations. Safiya blogs about Trinidadian food on “Life-span of A Chennette,” and her mother tests recipes after reducing them from the large volumes used to prepare food for crowds at the mosque.

In the same vein, notes Safiya, whenever there was a large function in the village that required the help of women—perhaps for the ceremony beginning a Hindu wedding, or the celebration of Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights—all the ladies in town were called upon, and her mother, Nazira, especially was asked to join in making sweets.

“We didn’t participate in the fetes or dancing, but when there was a village ceremony, we participated in the cooking because we were part of the community,” says Safiya. She adds that she, her mother and sisters could help all the more easily at Hindu functions because they were vegetarian affairs, thus mooting any question about Islamic halal dietary codes concerning meat.

Many point to the presidency from 1987 to 1997 of Noor Hassanali, the country’s first Indian president and the first Muslim head of state in the Americas, as a watershed in the history of social relations among Muslims and non-Muslims in Trinidad. It was the efforts of his wife, First Lady Zalayhar Hassanali, often made through food, that perhaps provided the most tangible opportunities for cultural and culinary cross-pollination.

“When I became First Lady, I served East Indian, Chinese, Creole and Syrian foods at state dinners to demonstrate our nation’s diversity,” she says. “But one thing we never served was liquor or pork because we are Muslims.”

An informal café sells three serving sizes of pelau, the Trinidadian favorite that plays off Indian biryani but is browned in syrup in an African style and seasoned with Trinidadian “green seasoning,” hot pepper and coconut milk.

While there was at first some concern about how dignitaries both at home and from abroad would accept this, Hassanali says people respected the couple’s decision—including Great Britain’s Princess Anne, whom Hassanali recalls enjoying the First Lady’s freshly pressed juices from fruits grown on the presidential estate.

“Even though it was shocking to many for a head of state to create a restriction about things that are so integral to Western diplomatic etiquette and there were those who frowned on it, in the end people respected the Hassanalis’ decision,” says hotelier Gerard Ramsawak, who is also a founding member of a multicultural outreach association the works with the office of the president of Trinidad and Tobago.

As manager of Pax Hotel, a historic building on the grounds of Mt. St. Benedict, one of the island’s oldest monasteries, Ramsawak regularly attended state dinners that included diplomats, artists and business people throughout President and First Lady Hassanali’s tenure.

“Mrs. Hassanali’s secret was that she embraced the larger culture of Trinidad and Tobago—a culture that is a melting pot where we’ve learned to appreciate each other’s differences,” he says.

Today food continues to represent mutually influential exchanges among Muslim and non-Muslim Trinidadians. While in the past most non-Muslim Trinidadians enjoyed Muslim foods, largely thanks to the generosity of Muslim neighbors and friends, some foods have become such a common part of daily life they are readily available to all.

The sawine that is a must-have for Muslims at ‘Id al-Fitr has become so popular that major Trinidadian food manufacturing brands such as Chief and Sheik Lisha sell packaged, toasted vermicelli with premeasured spices so that anyone can make the dessert at home.

“Sawine is something we all like even though it’s an Islamic food,” says Ramsawak. “Chinese, Hindu, Christian—we all make it at home.”

The presence of halal meat shops and restaurants throughout the country, frequented by people of all faiths and ethnicities, are another example.

Sarina Nicole Bland is part of the island’s extremely small Jewish community. She, too, blogs about the diversity of the cuisine in her homeland. She says she appreciates the ubiquity of halal restaurants, ranging from Chinese to burgers, Indian, barbecue, Arab and more.

“I keep kosher, and the laws of halal are extremely similar,” says Bland. “It makes things a lot easier for me.” Among her favorite Muslim Trinidadian foods is “fat kurma,” another sweet dish that is often brought to mosques for Friday prayers. It is one of the many dishes that demonstrate the subtle difference between foods that are considered Muslim versus Hindu or simply Trinidadian. A crispy fried treat that is coated in sugar, the Muslim version of kurma is more like a tiny doughnut with a crisp crust.

“I’m not sure how or why the two versions came about, or why one became associated with Muslims or the other Hindu,” says Safiya. “But that could be said about a lot of our foods.”

Nazira says that paratha roti, which is the forebear to the overwhelmingly popular “buss up shut”—in which the paratha is torn or shredded and has become the default standard to eat with curries—was considered Muslim while dalpuri—in which the paratha is stuffed with ground lentils—was largely thought to be Hindu, and was once only made for special occasions. “Now both are eaten by everyone interchangeably,” she says.

Also widely popular is pelau, the Trinidadian version of biryani, a Persian rice dish brought to India by the Mughal emperors. It is an excellent example of the influence, adaptation and evolution of Muslim dishes within Trinidadian cuisine. The layered rice dish is made with meat that is “browned” in caramel syrup in the African style and seasoned with “green seasoning,” a local mixed herb paste, hot pepper and coconut milk.

Like the biryanis that are often served in mosques in India, Trinidadian pelau is an incredibly popular one-pot dish that is also often made in mosque kitchens, particularly after 'Id al-Adha (Feast of the Sacrifice), in which cows, sheep and sometimes goats are sacrificed and the meat cooked immediately, while fresh. At the same time, pelau made from chicken or beef is a pan-Trinidadian dish often made for large gatherings and, especially, Sunday lunch with the family.

Even as the cuisine of Muslim Trinidadians has crossed over into larger culture and also been influenced by the culture around it, culinary evolution continues. A new wave of “Muslim food” is, again, changing the way Trinidadians eat—mostly in the form of the shawarma stands, locally called gyro (jie-roh), that now line major boulevards in towns, from the capital of Port of Spain in the north all the way down to San Fernando, the large oil-and-gas city in the south and, seemingly, everywhere in between.

Almost exclusively the bailiwick of the newest Syrian refugee immigrants, these stands range from independent operators, like Hassan’s, Yousef’s and Original’s, all the way to franchises like Pita Pit and even Lawrence of Arabia. Gyros are rapidly overtaking “traditional” fast-foods like doubles, a curried chickpea sandwich and oyster shooters from mangrove oysters, as the go-to after-party food for the clubbing crowd.

“The people line up for gyros every night,” says Zuher Dukhen who with his brothers arrived in Trinidad within the last few years. At their takeout stand, named Sami’s Arabian, they make their meat daily, hand-forming it using traditional methods. “Mostly we serve chicken because that is okay for most everybody—Hindu or Muslim.”

While for now the fare of this new food community remains fairly true to its ethnic origins, if the history of this island is any indication of the future, then it will not be long until it, too, is adapted, assimilated and in turn influenced.

“It wasn’t easy to make pure Arabic foods when our grandfathers first came,” says Adam Abboud, a Syrian-Lebanese Trinidadian whose Christian ancestors arrived more than a century ago. “They made do using things like the local shado beni for cilantro and patchoi for spinach. We made shankleesh cheese using cow’s milk instead of sheep’s milk. Now, it’s our own Trinidadian thing, and it’s what we prefer.”

Shankleesh is a homemade cheese made from aging strained yogurt (labneh) that is then rolled in spices and herbs, most often the Lebanese thyme called za’atar. Abboud is the proprietor of Adam’s Bagels, an eatery that bakes Arab breads onsite and serves olives, olive oil, herbs and spices imported from Syria and Lebanon, as well as locally made shankleesh.

Safiya Ali agrees. “My mother’s father was a Syrian Muslim who came here in the 1940s, and my mom made plenty of kibbeh and falafel when I was growing up, but I remember having to travel to Port of Spain to get the ingredients she needed. They weren’t so common as they are now,” she says.

For Trinidadians, these cultural nuances are just part of what it means to be Trinidadian.

Nazira Ali recalls attending mosque school every evening as well as the village Sunday school while she was growing up—with children of all faiths.

“We still all identified with our own religion,” she says. “Whenever the lesson was about biblical stories—like Ibrahim or the story of Christmas—we’d share our version of what Islam says about it,” she explains. “It was just learning. We grew up together and respected each other, in practicing our faith and in sharing our food.”

About the Author

Jean Paul Vellotti

Jean Paul Vellotti is a photographer whose work illustrated Sweet Hands and has appeared also in The New York Times, National Geographic Traveler, Caribbean Travel & Life, Islands and more.

Ramin Ganeshram

Ramin Ganeshram is author of Sweet Hands: Island Cooking from Trinidad & Tobago(Hippocrene Books, 2010).

You may also be interested in...

Nourishing Hope: A Conversation With Barbara Abdeni Massaad

Food

Forever Beirut—a collection of 100 traditional Lebanese dishes, each accompanied by a personal story—is her way of processing her own grief in the wake of the explosion while preserving cherished customs and recipes and helping in recovery efforts.

Histories on a Plate-Reflections on Food and Migration

Food

History

Muhalbiyat al-sagoo - Sago and Lychee Pudding

Food

Obtained from the trunks of various palms, sago is used across Asia as a thickener for soups and stews and to make pudding. You can substitute other soft, sweet fruit like plums or pineapple, but the sweet juice of the lychee blends very well with milk. This is an exotic take on the traditional sago pudding popular in Gulf cuisine, made with sago, sugar and spices.