“A fellow with a red bag … for a coat; with two red bags … for trousers, with an embroidered and braided bag for a vest, with a cap like a red woolen saucepan; with yellow boots like the fourth robber in a stage play; with a mustache like two half-pound paint brushes, and … a sword-gun for a weapon, that looks like the result of a love affair between an amorous broadsword and a lonely musket; discreet and tender—that is a Zouave.

“A fellow who can pull up a hundred and ten pound dumbbell; who can climb up an eighty foot rope, hand over hand, with a barrel of flour hanging to his heels; … who can jump seventeen feet four inches high without a spring board; who can tie his legs in a double bow knot round his neck without previously softening his shin bones in a steam bath; … who can take a five shooting revolver in each hand and knock the spots off the ten of diamonds at eighty paces, turning somersaults all the time and firing every shot in the air—that is a Zouave.”

So wrote a western Virginia newspaper reporter, tongue firmly planted in cheek, describing a strange and unprecedented military phenomenon sweeping America in the months leading up to the Civil War in 1861. Americans were going nuts over a new kind of fighting force: Zouaves, Algerian-style fighters introduced to the Western world by the French during the Crimean War.

The Zouaves’ heritage was North African, running back to the indigenous Berber fighters who served the Arab dey, or ruler, of Algiers prior to the French occupation of 1830. Initially recruited into the French military, by the time of the Crimean conflict in the mid-1850s almost all of the Zouave troopers were French.

In 1855 us Army Captain George McClellan, who was stationed in Europe as an official observer of the Crimean War, had witnessed the Siege of Sevastopol and observed the French Zouaves in action against Russian troops. McClellan, who would later command the Union Army of the Potomac in the Civil War, praised the Zouaves “as the finest light infantry that Europe can produce; the beau-ideal of a soldier.” Other us officers and the American press shared his admiration for the unconventional troops.

Not long after that, Zouave units were springing up all over northern and southern states. As reporters put it, their drill performances were acrobatic, and their battle cries of “zoo-zoo-zoo!” had men cheering and women swooning.

By the early 1860s, when North and South took to the battlefield, about a hundred Zouave volunteer regiments entered the fray—more than 70 for the Union and about 25 smaller units, mostly companies, for the Confederacy. (A regiment was comprised of about 1,000 men, divided into 10 companies.)

“Zoo-zoos” fought throughout the war, from First Bull Run to Antietam, and from Gettysburg to Appomattox. The first Union officer to die in action was a Zouave. So was the first Union soldier to win the Medal of Honor. And the last Union trooper to die before the war ended in 1865 was a Zouave. Fans of the Zouaves thought of them as superheroes; critics dismissed them as showboaters.

Today some continue to make light of the Zouave units that served in that bloody and divisive conflict, suggesting they were little more than acrobats in Orientalist dress—a fashion fad that came and went in a few decades. The Zouave uniform was indeed colorful by American standards, with bright red baggy trousers, short braided jacket, vest and tasseled fez. The outfit was designed for warm climates and rugged terrain. (It occasionally proved to be a fatal drawback, too, as the vivid colors made Zouaves easy targets on a battlefield.)

But those who study the Zouaves’ role in the Civil War realize they were about much more than style. America’s interest in the French Zouaves was fundamentally military: us officers were impressed by the fast-moving, agile fighting style inspired by the Algerian Berbers who developed it. On July 20, 1860, The New York Times burbled:

If the Zouaves should be deprived by siege of their ammunition, they would fight with the butt end of their guns; if by stratagem they should lose their guns, they would throw stones; if there were no stones, they would indulge in fistiana, and if their hands and feet were cut off, they would “butt” with their heads and pummel with their stumps.

Zouaves won admiration also for their compassion for victims of war. The Atlantic Monthly in August 1859 described how French Zouaves escorted a large group of “prisoners, wounded, and helpless women, old men and children” across the Algerian desert to their home villages. The troopers “behaved like very Sisters of Charity, rather than rough bearded soldiers,” sharing their food and water, feeding orphaned babies with ewes’ milk and carrying the infants to their destination. Zouaves developed remarkable unit cohesion and morale, modeled on the close relationships of the French family. It was common for soldiers to refer to their commander as “Father.”

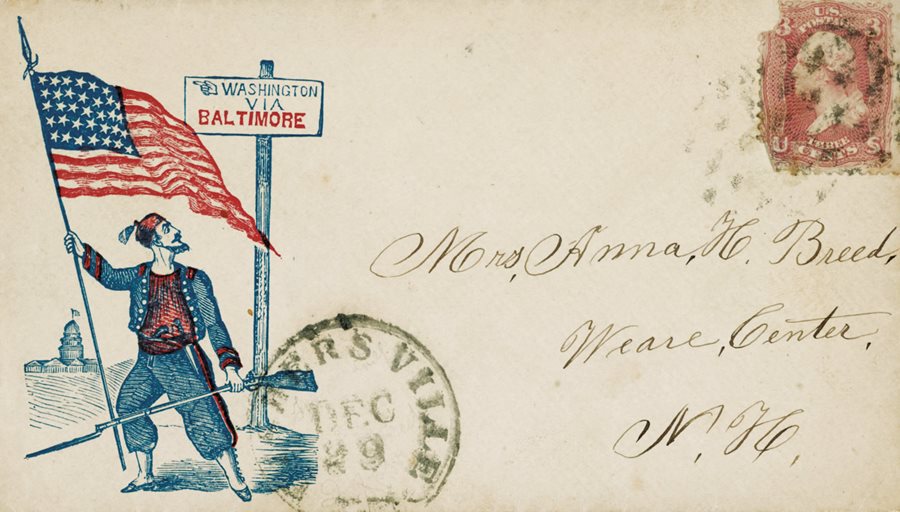

Newspaper coverage of the Crimean War and other European conflicts, backed up by engraved illustrations in magazines like Harper’s Weekly, had given Americans ample exposure to the Zouaves. As the North and South readied for war, it was only natural that each side would look to them for potential advantage in the field.

The first Zouave unit to capture the national imagination was a cadet drilling company formed in 1859 in Chicago by a bright young New York law clerk named Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth. While studying law in Illinois, Ellsworth spent much of his spare time on another pursuit: military drill teams. He was fascinated by military science but had failed to qualify for the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. Undeterred and captivated by the Zouave craze like many of his generation, he threw himself into training drill teams and introducing them to Zouave methods.

Ellsworth pursued two career tracks. On the one side, he studied legal practice by working as a law clerk. On the other, he worked during his free time as a drill instructor with cadets in Rockford, Illinois, and Madison, Wisconsin—and eventually in Chicago.

Ellsworth’s interest in the Zouaves intensified under the instruction of his fencing instructor, a former Zouave physician and expert swordsman named Charles DeVilliers, who had served in the Crimean War. From the Frenchman, Ellsworth learned the ins and outs of Zouave drill and tactics. He took command of a local military drill team called the Rockford City Greys, and in time his reputation as an effective drillmaster spread.

An eyewitness recalled the Greys’ performance:

They would fall to the ground, load their guns, fire, turn over on their backs, fire again, jump up, run a few steps, fall, then crawl on their hands and feet as silent and quick as cats, climb high stone walls by stepping on each other’s shoulders, making a human ladder.

Members of the National Guard Cadets of Chicago, a bankrupt and dispirited militia company, saw Ellsworth’s Greys perform this new system of drill that combined movements prescribed in the military manuals of American officers Winfield Scott and William Hardee with the athleticism and flamboyance of the French Zouaves.

It was not long before Ellsworth was offered command of the National Guard Cadets. At first he declined because he had just become engaged to marry the daughter of a Rockford businessman. When his putative father-in-law expressed concern that Ellsworth would not be able to provide for his daughter, Ellsworth assured him he would return to his law studies in Chicago. But then he told his fiancée in a letter that he had a plan:

I have changed my mind and have taken command of the Cadets for a limited time. I did not do so for the mere pleasure of commanding them, but I have an object in view which would justify me even in laying aside my studies entirely until after the Fourth of July. It was no idle move on my part I assure you and it throws a great additional labor upon me.

Zouave-inspired children’s clothing became widely popular, and boys such as this unidentified Union drummer served the military in Zouave dress.

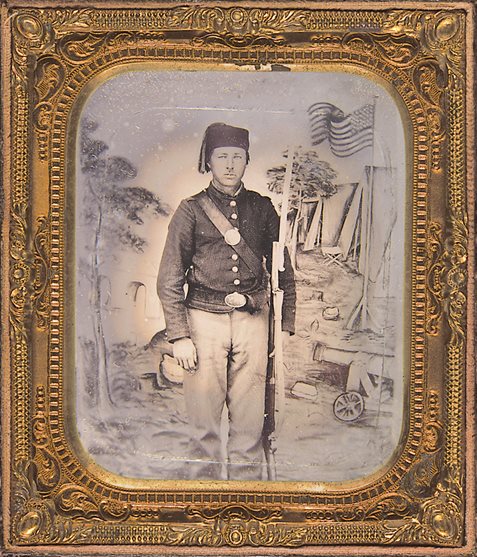

Outfitted with a Zouave fez and equipped with an 1862 Zouave-style sword bayonet, this unidentified Union soldier posed for a portrait against a backdrop depicting a Union military camp

Ellsworth quickly transformed the moribund militia company into the United States Zouave Cadets. He began developing dramatic exercises, and under his training, in 1859 the Zouave Cadets won the national military drilling competition in Chicago.

Ellsworth advocated more than military discipline: He advocated also an unbending work ethic, the highest level of physical skills, and exemplary morality that renounced alcohol, pool halls, bawdy houses and any hint of scandal. This instilled a powerful sense of loyalty among his men, and Ellsworth booted out 12 cadets for failure to uphold his standards.

The 50 who followed his rules became a smash hit. They traveled throughout the country, visiting major cities of the Midwest and Northeast performing acrobatic drill demonstrations at fairs, parades and other events. They wore uniforms designed by Ellsworth: a dark blue jacket trimmed in orange and red, a red sash, loose red trousers and a bright red chasseur cap or a flat-topped, short-visored kepi with gold braid.

On July 4, 1859, the cadets staged a parade in Chicago before Tremont House for the mayor and city council. Ellsworth, in his personal journal, described their reception: “The Chicago Tribune and Press … after giving the company a long but flattering notice concluded by saying, ‘We express the opinion of all who saw the drill yesterday morning when we say the company cannot be surpassed this side of West Point.’”

One journalist commented: “Even their most sanguine friends were surprised at the wonderful precision, rapidity, and difficulty of their drill…. Major Ellsworth has done nobly and received well-merited applause.”

One of those who witnessed a drilling performance that summer in Springfield, Illinois, was a lawyer named Abraham Lincoln. He was greatly impressed by Ellsworth’s leadership and organizational skills, and when he discovered the young man was studying law as well, he acted. At this point, Ellsworth’s two career tracks converged. In 1860 Lincoln offered him a job as a clerk in his law office in Springfield.

And so Ellsworth joined the team of a man many believed was destined for the presidency. John Hay, Lincoln’s personal secretary, became close with Ellsworth and in July 1861 wrote in The Atlantic Monthly about this pre-election period:

Ellsworth found himself for his brief hour the most talked-of man in the country. His pictures sold like wildfire in every city of the land. School-girls dreamed over the graceful wave of curls, and shop-boys tried to reproduce the Grand Seigneur air of his attitude. Zouave corps, brilliant in crimson and gold, sprang up, phosphorescently, in his wake, making bright the track of his journey.

Ellsworth and Lincoln, too, became good friends, and in the fall, the young clerk helped the lawyer with his presidential campaign. When President-elect Lincoln moved in February 1861 to Washington, D.C., Ellsworth accompanied the First Family and stayed at the White House, charming the Lincoln children and their parents alike. The President arranged several government job interviews for Ellsworth, but the young man dreamed of heading a military regiment and had little interest in office work.

Just before the outbreak of the war, Ellsworth traveled to New York, where he put together the 11th New York Infantry Regiment. Popularly known as the Fire Zouaves because most of its soldiers were recruited from the city’s volunteer fire departments, the 11th New York proudly wore red firefighter shirts as part of their Zouave uniforms. And like French Zouaves, the troopers shaved their heads.

Ellsworth brought the newly drilled regiment to Washington, D.C., where it was sworn into federal service on May 7 at the us Capitol, in a ceremony attended by President Lincoln and his son Tad. That same day, Ellsworth was promoted from the rank of second lieutenant to colonel. Two days later, the Willard Hotel, a local landmark, caught fire, and the regiment of New York firefighters rushed to the scene. Without ladders, and sometimes resorting to standing on each other’s shoulders to get to the fire, Ellsworth’s Fire Zouaves put out the blaze and won the hearts of the city.

On May 24 the Fire Zouaves became part of the first Union force to occupy Confederate territory when they captured the river port of Alexandria, Virginia, across the Potomac River from Washington. During the fighting, Ellsworth decided to cut down the Confederate flag that flew atop Marshall House inn. The flag was an enormous two and a half by four meters—so large President Lincoln had seen it from his office in the White House. It was a fatal mistake. As Ellsworth carried the captured flag down the staircase, the inn’s owner, James Jackson, met Ellsworth with a shotgun and killed him. Fire Zouave Corporal Francis Brownell in turn fatally shot Jackson, which earned Brownell the Medal of Honor—the first in the war.

When Lincoln heard the news, eyewitnesses said he wept openly and exclaimed, “My boy! My boy! Was it necessary this sacrifice should be made?” Ellsworth’s body was brought back to the White House, and his casket lay in state in the East Room.

From there the casket was taken to New York City Hall, where thousands came to pay respects to the first man to die for the Union cause. “Remember Ellsworth!” became a Yankee rallying cry, and the 44th New York Infantry Regiment was nicknamed Ellsworth’s Avengers.

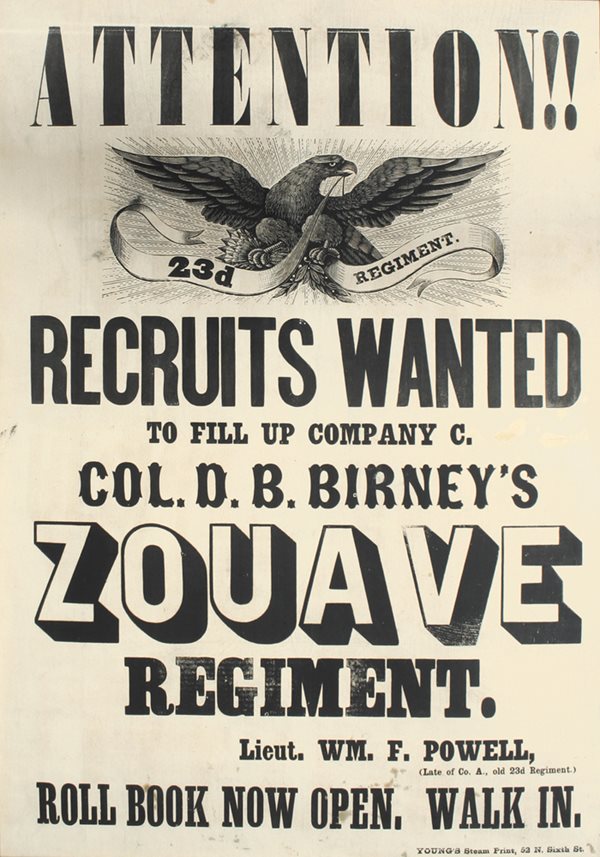

However, the first Zouave regiment to officially enter the Civil War was Hawkins’ Zouaves, the 9th New York Infantry Regiment, which mustered on April 23, 1861. Other states in the North and South also saw a rapid creation of Zouave units. A French-language newspaper in New York commented with pride, “Il pleut des Zouaves” (“It’s raining Zouaves”), as unit after unit mustered up.

These papier-mâché toy Zouave soldiers sport the red pantaloons, blue jackets with vests and dress turbans that came to characterize the Zouave uniform—even though colors and designs actually varied widely among Zouave regiments. Eye-catching on parade, such colorful outfits only made Zouaves more visible in the field.

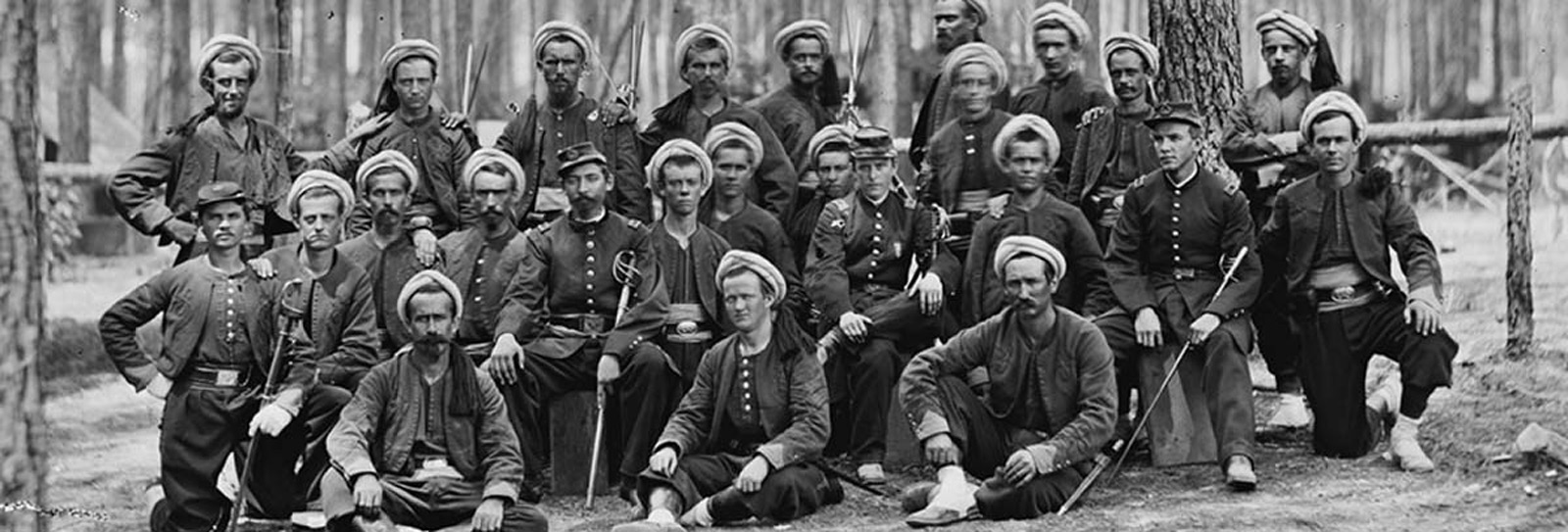

Each regiment dressed in the Oriental style, but uniforms varied widely depending on available fabrics and the whims of commanding officers. Some units featured the red balloon trousers, others dark blue or sky blue, and some wore the less baggy chasseur cut. Some regiments sported blue vests, others red. Sashes could be light or dark blue, turquoise or red. Some units were known for the tasseled fez of the original French Zouaves, with wrap-around white turbans for dress wear, and others wore a variation of the French kepi, which became popular also among conventional American military units of both the Union and the Confederacy.

The “Zouave craze” was so intense that tailors began creating Zouave-style uniforms for young children, and customers included President Lincoln’s son Tad and General Ulysses S. Grant’s son Jesse. Zouave paper cut-out dolls, coloring books and other toys began appearing in the marketplace. Women’s fashions also adopted the Zouave style with embroidered jackets, short vests and other Eastern flourishes.

The Zouaves’ popularity was reinforced by the spread of Europe’s Romantic movement throughout the us in the early and mid-1800s, which exerted a strong influence on literature, the arts and popular culture. The dashing Zouaves, with their devil-may-care attitude toward combat, their moral enthusiasm, individualism and emotion, epitomized Romantic ideals. They also captured the essence of Orientalism with its vision of an exotic yet alluring East.

This jacket and fez belonged to a member of the Collis’s Zouaves, the 114th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regiment. The regiment adopted the uniform of the French Zouaves d’Afrique, and it included French soldiers who had been members of French Zouave forces.

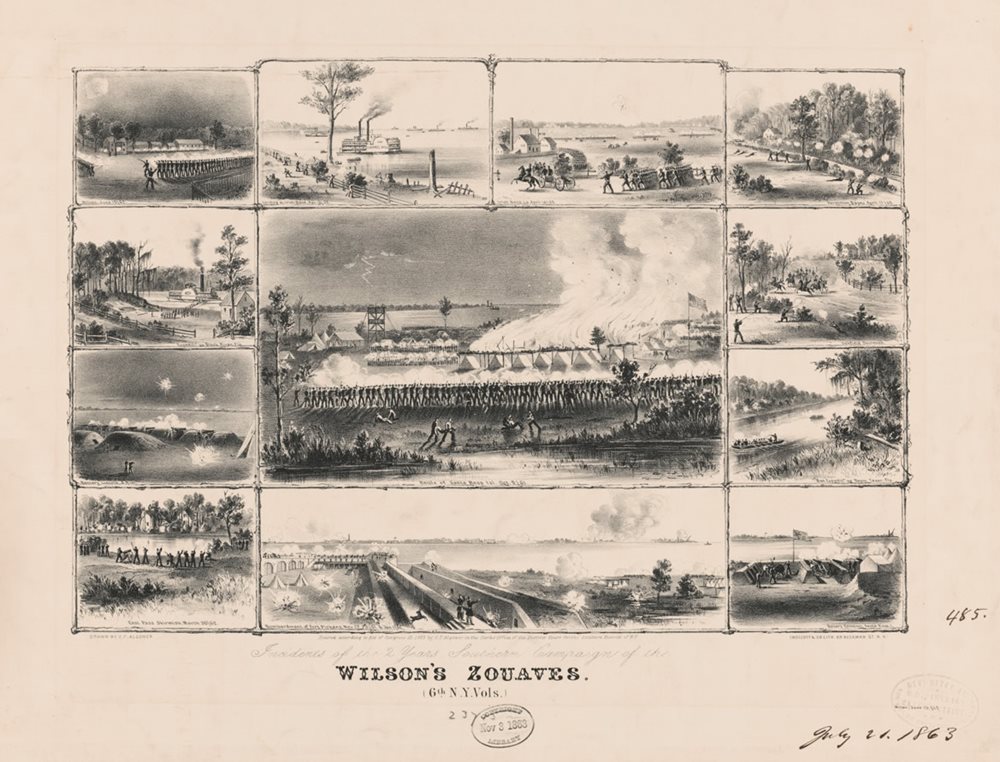

The best-known Union Zouave regiments organized out of New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Indiana. Among them were Duryée’s Zouaves (5th New York); Hawkins’ Zouaves (9th New York); McChesney’s Zouaves (10th New York); Ellsworth’s Fire Zouaves (11th New York); Collis’s Zouaves (114th Pennsylvania); Piatt’s Zouaves (34th Ohio) and Wallace’s Zouaves (11th Indiana). The most famous Confederate Zouave units, such as Wheat’s Tigers (1st Louisiana Special Battalion) and Coppens’ Zouaves (1st Louisiana Battalion), were set up, not surprisingly, in formerly French Louisiana. Though numerous—perhaps as many as 70,000 for the Union and 2,500 for the Confederacy—they served among vastly more numerous regular soldiers: some two million Union men and 750,000 Confederates.

Most of the Zouave units, particularly in the northern states, trained hastily in the early months of the war. Because time was short, they sometimes failed to meet European standards when it came to military training, tactical coordination and discipline—factors that had been so important to Ellsworth. Some regiments, however, excelled in drilling skills and unit discipline, such as Duryée’s Zouaves, the 5th New York, which General McClellan, who had seen French Zouaves in combat, in 1862 called the best-drilled regiment in the Army of the Potomac. The popular Louisiana units—Wheat’s Tigers and Coppens’ Zouaves—were reported to be first rate in drilling but otherwise somewhat undisciplined.

This photo of a Union officer in conventional uniform and a child decked out in a Zouave uniform, taken in Brattleboro, Vermont, testifies to the Zouave craze that swept America.

American Zouaves adopted the battlefield tactics of their French counterparts: speed, mobility and surprise. “Zouave tactics” meant that the men attacked in rapid advances of 100-200 meters, dropping to the ground between each advance and firing their rifled muskets. This was a distinct shift from the prevailing Napoleonic infantry tactics of tightly closed formations, often elbow-to-elbow in double-rank battle lines comprised of thousands of troops. However, in such formations, gun smoke drastically reduced visibility. Since gun smoke tended to rise, visibility was better for those lying on the ground. The Zouaves’ desired rate of fire was three rounds per minute, but in practice it was usually less, as soldiers struggled with their muzzle-loading muskets and sought to conserve limited supplies of ammunition.

The American Zouaves were not conventional soldiers, said Thomas Higginson, a white abolitionist who served as an officer in an all-black Union regiment: “Nobody knows anything about these men who has not seen them in battle. There is a fierce energy about them beyond anything of which I have ever read, unless it be the French Zouaves. It requires the strictest discipline to hold them in hand.” (The emphasis is in the original.)

Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace—later us minister to the Ottoman Empire and author of the 1880 historical novel Ben-Hur—described Zouave tactics used in the 1862 capture of Fort Donelson, Tennessee. Writing 22 years later in The Century magazine about the assault on the Confederate fort, Wallace explained the movements of two Zouave regiments he had led personally:

As the two regiments began the climb, the Eighth Missouri slightly in the lead, a line of fire ran along the brow of the height. The flank companies cheered while deploying as skirmishers. Their Zouave practice proved of excellent service to them. Now on the ground, creeping when the fire was hottest, running when it slackened, they gained ground with astonishing rapidity, and at the same time maintained a fire that was like a sparkling of the earth.

Zouave regiments distinguished themselves, earning high honors on the battlefield. No one ever doubted their courage in the face of enemy fire. Duryée’s Zouaves conducted a ferocious charge in 1863 at the siege of Port Hudson, Louisiana, losing 108 men, more than a third of their force, in one afternoon.

At Gettysburg Ellsworth’s Avengers took part in the heroic defense of Little Round Top during a major Confederate assault, taking heavy casualties. Collis’s Zouaves lost over half their riflemen at Gettysburg’s Peach Orchard. The 2nd Fire Zouaves, fighting alongside Collis’s force, also suffered grave losses. Elsewhere on the battlefield, a single Confederate enfilade volley dropped over 80 men of the 72nd Pennsylvania Zouaves, part of the famous Philadelphia Brigade.

Two Zouave regiments, the 140th and 146th New York (the latter Garrard’s Tigers), fought at Sanders Field at the 1864 Battle of the Wilderness in Virginia, losing more than a third of their forces in the battle. That same year, the 33rd and 35th New Jersey Zouaves lost more than half their men during the Atlanta Campaign.

Representing smartly clad Zouaves at a re-enactment battle in 2008 in Huntington Beach, California, Civil War reenactors today help preserve the memory of the Zouave troops who fought on both the Union and Confederate sides.

Zouave units saw combat in every major battle of the war. Difficulties in maintaining their ornate uniforms meant that later in the war Zouave soldiers sometimes had to settle for articles of clothing in conventional blue or gray. They did their best to keep the Oriental flavor of their uniforms.

In the North, the government tried to standardize the Zouave uniform, with limited success. Some conventional units that performed well on the battlefield were rewarded with Zouave garb. In the South, the Zouave uniform gradually disappeared; it was difficult enough for the Confederacy to secure the gray cloth for regular uniforms, much less expensive Eastern-style fabric.

On April 9, 1865, as General Robert E. Lee formally surrendered the Confederate Army to the Union commander, General Grant, at the courthouse in Appomattox, Virginia, the Zouaves suffered the war’s last Union fatality. Seventeen-year-old William Montgomery of the 155th Pennsylvania (part of the 5th Corps’ Zouave Brigade) was mortally wounded by a Confederate artillery shell just one hour before the truce took effect.

With the end of the war, the remaining Zouave volunteer units quickly disbanded. On the Union side, where Zouave dress had persisted, thousands of uniforms were sold as surplus and later continued to appear in ceremonies and parades across America. The last Zouave regiment, a militia unit from Wisconsin, retired its garb in 1879.

Many of Ellsworth’s Chicago Zouave Cadets had gone on to important posts in the Union Army during the war, and they continued to advocate their fallen commander’s Zouave traditions and high standards of leadership. For their last reunion, held in November 1910 at Chicago’s Wellington Hotel, eight former cadets showed up; five others were still living but unable to attend.

On the field at Antietam near Sharpsburg, Maryland, an obelisk honors the sacrifices of the the 9th New York Infantry Regiment, the first official Zouave regiment, mustered in April 1861. On September 17, 1862, 370 of the 9th’s soldiers faced battle, and 240 gave their lives.

The spark ignited by the Zouaves more than a century and a half ago is kept alive today by the Civil War reenactor movement, made up of hobbyists and researchers across the country who represent numerous military units on both sides (Ellsworth’s Avengers are represented by a group in Bakersfield, California). These units commemorate the major events of the conflict and celebrate national holidays by staging encampments and mock battles throughout the area of the conflict—and even appearing in television and motion-picture productions. The recreated Duryée’s Zouaves, for example, organized in 1971, is one of the oldest and most respected “living history” units in the country.

The rapid disappearance of the Zouave units signaled their limited long-term impact on tactical theory and organization in the us military. They were widely viewed as “elite” units, modeled on the best France had to offer. At the same time, they were transitional, a “missing link” between the armies of the 18th and 20th centuries. There were doubts over the value of their fluid, Berber-influenced guerrilla-style tactics, particularly when coupled with flashy, colorful uniforms and the emphasis on formal drilling. Clearly, however, the Zouave units generally brought out the best in their soldiers. In this sense, the Zouaves influenced the course of the Civil War, and they will long be remembered for that.

You may also be interested in...

Reflections of Knowledge

History

Science & Nature

Part 3 of our series celebrating AramcoWorld’s 75th anniversary highlights the magazine’s emphasis on experts and institutions that push the boundaries of present-day knowledge while paying homage to historical figures and writings that paved their way.

America’s Arabian Superfood

Food

History

In recent years in the United States, dates have been trending as a nutrient-dense, easily transportable source of energy. Nearly 90 percent of US-grown dates are from California’s Coachella Valley. Yet the date palm trees from which they are harvested each year aren’t native; they were imported from the Arab world in the 1800s. Over the years, they have become a part of Coachella’s agricultural industry—and sprouted Arab-linked pop culture.

Celebrating 75 Years of Connection Stories and Culture

Arts

History

Since its origins in 1949 as a company newsletter for Aramco, AramcoWorld has evolved to focus on global cultural bridge-building across the Arab and Muslim world and beyond.