America’s Arabian Superfood

- Food

- History

- Foodways

10

Written by Alia Yunis

Photographed by Stuart Palley

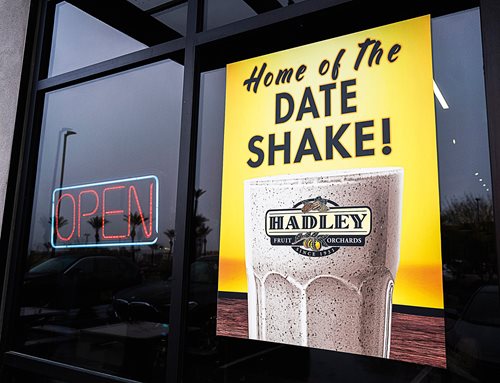

If you like an easy, sweet summer drink, perhaps try blending dates, cold milk and vanilla ice cream. The drink is known as the “California Date Shake” and has been associated with the state’s Coachella Valley for decades.

In the US over the past few years, dates have been trending as a superfood, often promoted in the recipes of energy smoothies or nutrition bars. As medical institutions such as the Cleveland Clinic note on their websites, numerous studies show that dates provide long-lasting, easily transportable energy, are rich in minerals like iron and potassium, and may help reduce cholesterol, keep blood-sugar levels steady and aid digestive health.

“People really know about dates now, and the health-food market has led the way in increasing interest,” says Mark Tadros, co-owner with his father of Aziz Farms, an independent date-producing and -packing facility in Coachella Valley.

Tadros says that close to 90 percent of the dates grown in the United States are from Coachella Valley with the Yuma, Arizona area accounting for much of the other 10 percent. Yet date palm trees are not native to the US. Rather, they were imported from the Arab world in the 1800s. Over the years, they have become a part of the Coachella agricultural industry—and sprouted Arab-linked pop culture.

The valley’s signature milkshake treat has been popular since the 1920s and is a tourist attraction itself. Shields Date Garden, one of the initial shops, has beckoned passing travelers for 100 years to try its date shake. A café and date shop surrounded by date palms, Shields’ bustling aisles are packed with curious shoppers who struggle to pronounce the different types of dates for sale, especially the Barhi, Zahidi and Halawa varieties, which all originated in Iraq.

“The temperature and climate of Basra, Iraq, was very similar to the valley,” says Robert Krueger, horticulturist and research leader at the United States Agriculture Department’s Agricultural Research Service National Clonal Germplasm Repository for Citrus and Dates in Riverside, California. He says this explains why American agricultural explorers, sent out by USDA in the late 1800s to acquire crops for the US’ newly acquired California and Arizona deserts, saw the potential of planting date palms, particularly in the Coachella Valley. The explorers, he says, would bring offshoots from some 70 varieties from the Middle East and North Africa, especially Oman, Morocco and Algeria, to the US for experimentation.

Over the years US farmers have cultivated a number of new date varieties. Floyd Shields, founder of the store, was one of the pioneer date farmers in the valley.

“Like all the early growers, Mr. Shields did a lot of date experimentation,” says Heather Raumin, co-owner of Shields today. “Every date has its own unique flavor and texture,” says Raumin, “and everyone has their own taste preference.”

Raumin is most fond of the story behind the “Blonde” variety named by Shields for his wife, Bess. “The Blonde variety is the basis of Shields’ signature date powder,” she says, and it can be activated into a paste with the addition of liquid. It was one of the first successful American experiments in preserving dates beyond their natural shelf life and the building block for Shields’ date shake.

Much of California’s date history was recorded in the late 1990s and early 2000s by Pat Laflin, whose family once owned Oasis Date Gardens, one of the largest date growers. Her research shaped the Coachella Valley Date Museum, located in the city of Indio in a former school library. Managed by volunteers, the dimly lit museum’s simple displays show the evolution of tools for cultivating dates as well as photos of the early US date explorers and farmers.

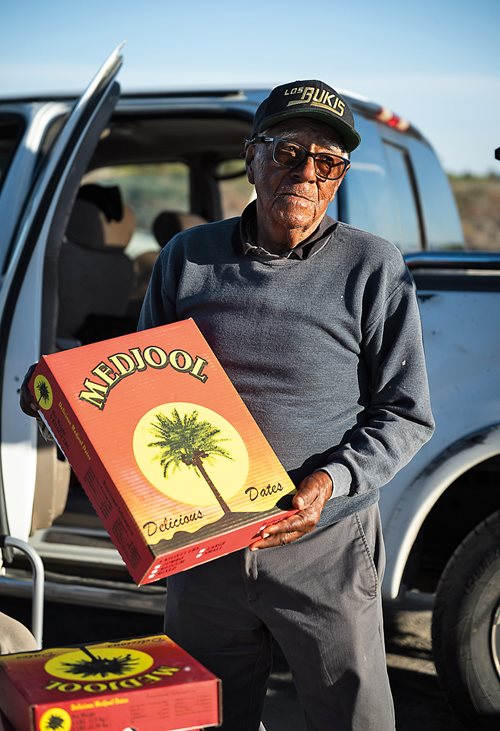

The museum also tells the story of the two most important dates in the valley. In 1903, independent farmer and explorer Bernard G. Johnson brought back 129 “Deglet Noor” offshoots from Algeria. The cultivar would become known as the “queen of dates” because of its ease of growth and dry texture, which makes it easy for pitting for baking. In 1927, the USDA’s Walter T. Swingle brought back what would become known as the “king of dates”: 11 offshoots of the Medjool, a soft, jammy Moroccan variety threatened by disease at home.

“Nine shoots survived by the time they reached the USDA Experiment Station,” says Diane Laflin Burke, the daughter of Pat Laflin. “They were nurtured into 72 shoots, and of the 72, my grandfather got 24. And from there, we ended up with 200-some acres of dates.”

Compared to the Arab world, where in desert areas dates were the most important source of sustenance, the fruit has not been a significant part of the American diet. Nor are they imbued with religious significance, as they are for many Muslims during Ramadan. Coffee importers first brought dates from the Arabian Gulf in the mid-19th century, most notably Hills Bros., the largest coffee importer. Hills Bros. fostered the country’s appetite for this exotic fruit by marketing dates with camel-caravan illustrations.

“A hundred years ago, when the date industry began, America was in a pop-cultural relationship with the greater Middle East, but traveling there was not feasible for most Americans,” says Sarah Seekatz, a professor of US history at San Joaquin Delta College, who has researched the culture around the date industry. “Americans had no language for the desert, except religious texts, The Arabian Nights and Hollywood films and shows like ‘The Sheik’ and ‘I Dream of Jeannie,’ so the community made those connections.”

While Coachella Valley is known today mostly for music festivals and golf resorts and the campy love of Arabia faded away in the 1970s, the remainders of that history can still be found. Coachella Valley High’s mascot is still the Mighty Arab. Pageant winners at the Riverside County Fair & National Date Festival have been crowned Queen Scheherazade and Princess Jasmine since 1947 at a fairgrounds anchored by Disney-like minarets. The town of Walters became Mecca in 1904, when the state’s first USDA Date Experiment Station was located there.

The California date industry today has benefited from a decades-long wave of immigration from the Middle East and North Africa. For Tadros, the growth in the Muslim population has been a great boost for business and is the market on which he focuses. But California dates face stiff competition from other countries and with other crops that are much easier to grow, like vegetables and citrus. “Dates are not a short-term investment” he says. “I’m lucky if I am harvesting from that offshoot in 10 years’ time.”

One of the greatest challenges is the spring pollination season. Date pollination is the highest-paid farm labor in the valley because it takes special training and involves risks. Date-trunk thorns and scales can pierce skin. “Date trees cannot pollinate by themselves,” Tadros says, explaining the precise cutting and binding required. “You have to bring the male to the female if you want a good yield, which can be 200 or more pounds from one tree.”

Today, date pollinators, called palmeros in Coachella, ride on mechanical lifts to reach the tops of trees, one of the many innovations that have developed the date industry. Tadros is well-versed in the contributions US growers have made to the industry. Prime among them are mechanized cleaning and freezing methods that allow dates to last far longer than the few weeks they did when they used to arrive on boats from the Arab world. Many California growers have shared their techniques with growers in the Middle East. Tadros has also been impressed with inventions coming out of the Middle East, like a new lift and some unique grading equipment.

“The date-growing region here wouldn’t exist without the date-growing region in the Middle East. We were fortunate to get the trees from there—and initial knowledge,” says Tadros. The future of date production is set to continue to be an exchange of knowledge and innovation between the Arab world and the US, as the appetite for the fruit grows beyond its original homeland.

About the Author

Alia Yunis

Alia Yunis, a writer and filmmaker based in Abu Dhabi, recently completed the documentary The Golden Harvest.

Stuart Palley

Stuart Palley is a photographer based in Southern California focusing on documenting climate change, environmental issues, and infrastructure in the American West. He is a contributor to National Geographic magazine among other publications. His memoir Into the Inferno: A Photographer’s Journey Through California’s Megafires and Fallout was published in 2022.

You may also be interested in...

Of Spice, Home and Biryani

Food

Slow-cooked with meats, vegetables and spices that vary all across the subcontinent of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, biryani “speaks to love, time and patience” for those who grow up with it, and to dazzling, addictive blasts of flavor to everyone else. No wonder it’s a rising global food star.

Cooking Food For the Body, Mind and Soul: A Conversation With Chef and Restaurateur Asma Khan

Food

Asma Khan introduced her blend of South Asian food to England in 2017 when she founded the Darjeerling Express, a brick-and-mortar restaurant in London that started off as a supper club.

Nourishing Hope: A Conversation With Barbara Abdeni Massaad

Food

Forever Beirut—a collection of 100 traditional Lebanese dishes, each accompanied by a personal story—is her way of processing her own grief in the wake of the explosion while preserving cherished customs and recipes and helping in recovery efforts.