I have never had real biryani. I have been told this by a Pakistani cab driver, an Afghani baker, an Indian writer, an Emirati student and other self-proclaimed authorities on the relationship of rice, meat, vegetables and spices. I concede that in one sense they are right.

I didn’t grow up with biryani, and for those who have, the only real biryani is the one made in his or her own city, neighborhood or, more likely, family kitchen. Biryani’s power lies not only in its wildly diverse, complex flavors that make first-timers wonder what they have been missing all their lives, but also in its connection to place, perhaps even more so in an era when so many of us live far from where we grew up.

Case in point: Bilal Lakhani, a columnist for Pakistan’s Express Tribune, grew up in Karachi, on the coast, and he went to business school at age 18 in Lahore, in the northeast. He recalls how at the time he and his Karachi buddies were really missing biryani. Having little money, they thought they would find a wedding to crash because weddings, he says, is where you can always find biryani. Pretending, as needed, to be friends of one family or the other, they staked out a wedding and got in the food line.

“Our daring plan was a disaster,” Lakhani recalls. “The biryani didn’t have aloo (potatoes)! How can you have biryani without aloo? That’s an abomination.”

He speaks like a poet of the savory spices that infuse aloo in a good biryani, yet in other places—such as Lahore—the very presence of aloo is, well, anti-biryani. The feelings run deep.

A common biryani origin story begins in the early 1600s with Mumtaz Mahal, wife of Mughal emperor Shahab-ud-din Muhammad Khurram, better known as Shah Jahan. While visiting soldiers at their barracks and seeing them underfed, the story goes, she ordered the cooks to prepare a dish of rice and meat, which they prepared over a wood fire with aromatic spices. “Soldiers had to have their stomachs filled to have the energy to fight,” says Chef Raman Khanna, who learned to cook biryani in the 1980s at the Oberoi Hotel in New Delhi alongside the Oberoi family’s personal chef, Baba Lul. The way the legends go, he says, “at night, military cooks would prepare a big pot of meat and rice and bury it and place coals on top. The next day, the soldiers who survived would come back and dig out the pot and eat.”

The general speculation about the dish’s origins among chefs and food historians includes a belief that Ottoman allies of the Mughals brought pilaf (rice with meat and other ingredients) to the subcontinent, where chefs infused it with local spices and experimented with its method of cooking. Others maintain that a more sophisticated version of the soldiers’ cooking was already popular with the the Mughals themselves when they came from Persia to what is now Afghanistan and that the spice trade that so enriched India’s ports also gave birth to biryani’s flavors. From the imperial palace to the estates of local landowners, those who could afford it employed cooks who refined and even personalized the dish with combinations of saffron, cardamom, rosewater and a host of other spices and aromatics.

When I think of making it or even eating it, the fundamental thing about biryani is that it speaks to love, time, patience. ... That is why it is such a celebratory dish.

—Sumayya Usmani

“That’s why there is always this feeling of something royal in eating biryani,” says Khanna.

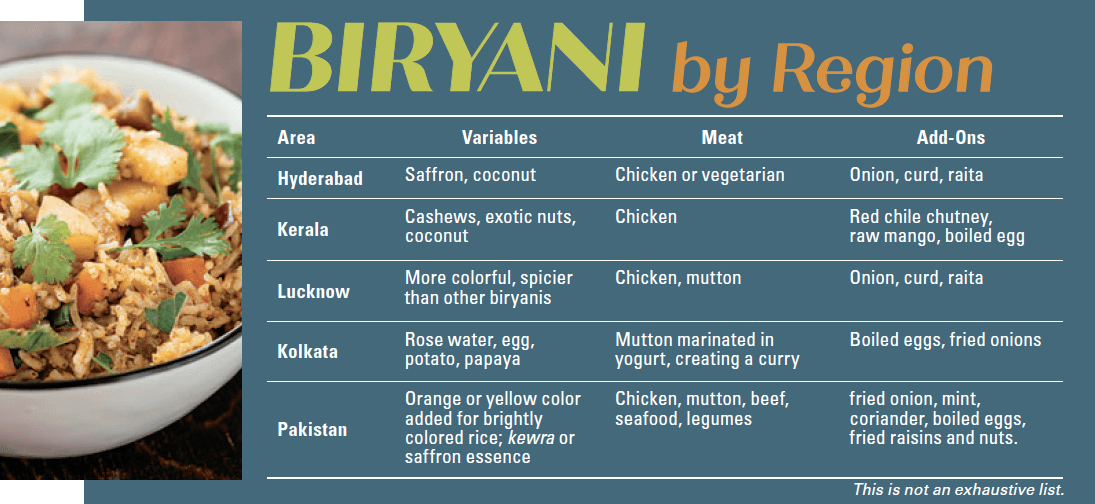

Two fundamental cooking methods for biryani emerged from the palaces of two regions of India.

The first is Kucchi biryani, which is considered Hyderabad-style, he explains. Here, raw meat is marinated for hours, placed in a dum (pot), “layered with rice in varying degrees of doneness” and then steamed.

“The flavors rise and impregnate the rice,” says Kripal Amanna, host of the YouTube show, Food Lovers TV.

The second is Pukki biryani, which is considered Lucknow-style. “Meat and spices are cooked separately until almost done, then layered with rice that is almost cooked, then placed on the dum.”

In both, the biryani is made with equal parts meat and rice, and in the case of potato biryani, 25 percent meat and 25 percent potato, according to Lakhani’s mother, Najma Rafiq. Traditionally, the top of the dum is lined with dough before ingredients are placed inside, and then the biryani takes a half hour to an hour to cook, depending on the size of the pot and biryani type, she says.

Khanna adds that regional biryani chefs may top the pots with coal, wood embers, charcoal or coconut husk, creating additional flavors specific to each region.

“The beauty of this in the Nizam and Nawab Palaces was that when the biryani was ready, the dough was lifted off and the whole dining room was filled with the aroma of the spices. That revelation is what made it into a signature item of India,” Khanna says.

In Lucknow, some versions cook the rice in milk, says Amanna, which makes it “subtler in their flavor notes.”

“The Hyderabad biryani is a brash, grab-your-palate biryani, whereas the Lucknow biryani is shy and more demure. You have to make more of an effort to know it,” Amanna says, explaining also how the Lucknow versions include essences like pandan extract that enhance aroma. “They are like a lady splashing on some perfume, as opposed to that robust Hyderabad biryani with its aggressive onion, garlic and ginger, which let the other spices play second fiddle.”

The variations of these two methods have expanded across the subcontinent. Amanna has filmed 25 shows that revolve around biryani, but that’s not nearly enough, he says.

“Biryani travels every 100 kilometers that you travel. I could easily do 200 episodes on biryani across India and not repeat a particular style,” he says.

He finds the best way to encounter new biryani culinary styles is when he’s traveling by motorcycle.

DB IMAGES / ALAMY

“You have to take a break every 100 or 150 kilometers. So, you stop and take in the sights and the aromas. You smell some rice and you follow it,” he says, pointing out how this method has allowed him to access hundreds of biryani establishments and recipe variations.

Amanna favors family-owned restaurants that have been making biryani for decades, if not more than a century, including the Rahamaniya Briyani Hotel in Ambur in the state of Tamil Nadu, which adds homemade curd to the meat and spices. He also highlights the Shivaji Military Hotel in Bangalore, where every day about 200-300 kilograms of meat are turned into donner (boat) biryani, which is served in a banana leaf basket that softens to flavor the dish.

Long before the motorcycle, there were ships, and that is how spices came to the Indian subcontinent, often via Arab traders. Pakistani cookbook author Sumayya Usmani spent much of her childhood on the ship her father captained, and her first memory of biryani is her mother stirring together the ingredients in an electric frying pan in the boat’s galley kitchen. Traveling by sea, Usmani’s mother took short cuts with the dish to preserve the limited number of ingredients that could survive the long journeys. Preparing biryani at sea also offered opportunities to add squid, mussels and prawns. Seafood variations often include a green masala of mint, coriander and chilis.

“When I think of making it or even eating it, the fundamental thing about biryani is that it speaks to love, time, patience,” Usmani tells me. “That is why it is such a celebratory dish.”

Usmani now lives in Scotland, where she teaches others to make biryani, including her 11-year-old daughter. Her own mother, Usmani says, taught her to use only basmati rice aged one to two years, because it fluffs, separates and tastes better.

“My mother has drilled this in my head. Unless your rice, after cooking, isn’t as long as one segment of your finger, it’s not worth cooking,” she says, laughing.

Khanna, too, agrees the best biryani cooking class is in a family kitchen.

“Indian chefs do not like to share their recipes,” Khanna says, remembering his early cheffing days at the Oberoi Hotel working for chef Lul. “I had to peel up to 60 kilos of onions every day and pound pastes until my knuckles actually bled in order to get his trust.”

Meat also varies by region. Goat—often called mutton in India—is the most traditional for biryani, but lamb and chicken are also used. In India’s south, in the state of Kerala, beef biryani is also a specialty. Kerala’s biryani was also much influenced by centuries of trade with the Arabian Gulf.

I asked Khanna, who has catered biryanis for royal weddings and vip events in the uae for a decade, including cooking the dish in the middle of the desert for 2,500 people during the first World Cup of Horse Racing, why so many people in the Gulf think of biriyani as a local dish.

“The spices and rice came to India through the Arabian trade routes, and we brought them back as biryani,” he says, noting that many chefs throughout the Arabian Peninsula hail from Kerala.

The dish continues to vary through time and across regions depending on environment, culture and availability (or lack) of ingredients. With some 30 percent of India eating vegetarian diets—and the popularity of meatless recipes in restaurants worldwide—meatless biryani is increasingly acceptable to biryani purists. But it comes with challenges: Vegetables, Ammana says, struggle to survive the heat of the dum. There are solutions though, like frying the vegetables first or adding them in at the end.

“The beautiful thing about biryani is that everyone can stake claim to it,” he says. “Biryani is one of the very few dishes in which people across the world can say, ‘This is our biryani.’ Everyone can make it their own.”

You may also be interested in...

Albania’s Resurging Cuisine

Food

After decades of decline under communist rule, food enthusiasts—including brother chef and baker Bledar and Nikolin Kola—are pioneering the return of the country’s traditional dishes. Chefs and other culinary aficionados are drawing on Albania’s 500-plus years of culinary heritage to reinterpret the foods of their ancestors. Their efforts are re-establishing traditions that were feared lost.

Tastes of Azerbaijan

Food

Azerbaijan has sat at a crossroads of Eastern Europe, the Middle East and Western Asia for centuries as a Silk Road hub and a gateway that empires routinely fought to control. That intersection also has manifested itself in the nation’s food—a complex and enticing stew of Turkic, Persian, Eastern European and other regional influences. This food diary explores the unique cuisines of each region.

America’s Arabian Superfood

Food

History

In recent years in the United States, dates have been trending as a nutrient-dense, easily transportable source of energy. Nearly 90 percent of US-grown dates are from California’s Coachella Valley. Yet the date palm trees from which they are harvested each year aren’t native; they were imported from the Arab world in the 1800s. Over the years, they have become a part of Coachella’s agricultural industry—and sprouted Arab-linked pop culture.