Kanga’s Woven Voices

Photographed by Samantha Reinders

Written by Amanda Leigh Lichtenstein

“It opens the channels for women to express themselves, to clap back, to be heard, to love, to laugh, to pray, to return a gaze to the world. It becomes to a woman whatever she wants it to be: a voice that she wears around her, a message to the world, poetry, a shield.” —Ndinda Kioko

Multifunctional, vibrantly colorful and affordable, kanga permeates the fashion landscape, especially on the semi-autonomous, predominantly Muslim island of Zanzibar, off the coast of Tanzania, where it is said to have originated. From sun-drenched rural fishing villages to the city streets of Stone Town, a historical district in Zanzibar City, Zanzibar’s capital, women and girls do more than merely wear the kanga: They weave it into daily life, from birth to death and in between, as East Africa’s original “social media,” worn and traded both for the dazzle of the designs and for the surprise of the messages.

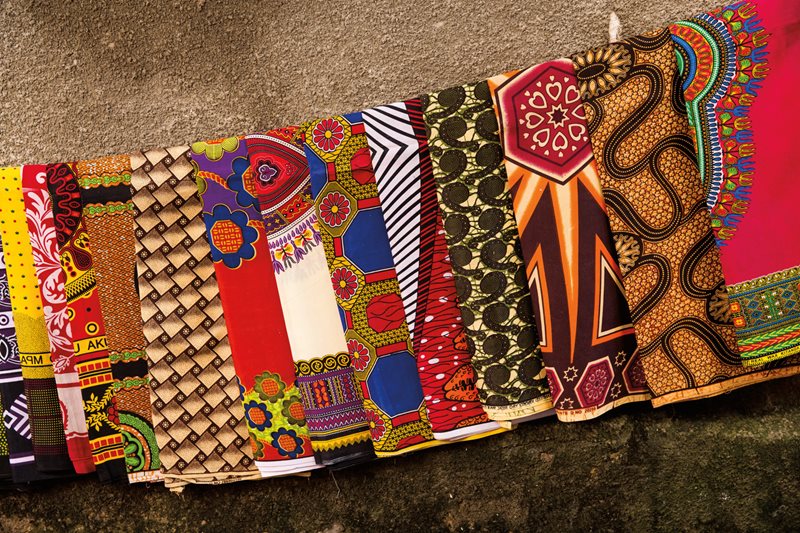

By definition, a kanga is a rectangle of cotton cloth comprised of a mji, or central design motif; a pindo, or patterned border; and a jina, or “name,” which is a Swahili proverb, aphorism or contemporary statement, usually printed in black bold capital letters against a white background along the edge between the motif and border. Kanga are machine-printed and sold in 1½ x 1-meter pairs. Women usually cut and separate the pair at the center, hemming the edges, and then they wear one piece as a head covering or shawl while the other cloth is wrapped around the waist.

Wrapped up in the kanga is also the history of Zanzibar itself. As far back as the first century ce, Yemeni and Persian traders used monsoon winds to sail the Indian Ocean. By the 12th century, trading posts, villages and mosques became well established both on the islands as well as along the coast from as far north as Mogadishu, now in Somalia, to as far south as Kilwa, now in Tanzania. When the Portuguese arrived in the early 1500s, they forced colonial rule and influenced trade in the region for more than 200 years. Among their legacies: a colorful square kerchief, known as leso.

As Zanzibar grew, hundreds of lateen-sailed dhows connected it with the African coast, Arabia, India, Persia and China. Traders brought iron, sugar and cloth; they left with shells, cloves, coconuts, ivory—and slaves. In 1698 Saif bin Sultan, the Imam of Oman, defeated the Portuguese in Mombasa, Kenya, and established an Omani stronghold on the coast. By the 1830s, Omani Sultan Said bin Sultan had established Stone Town, Zanzibar, as the official seat of Omani power.

The sultans of Oman ruled in the region for more than two centuries, creating a complex and highly stratified social system, with positions signified in part by clothing. Legend has it that women who sought to elevate their status abandoned plain black cotton kaniki cloth in favor of looks that would distinguish themselves as both upwardly mobile and free. (Slavery ended in Zanzibar in 1897.) They purchased leso in lengths of six meters, and then cut the six into two lengths of three, breaking them down further into three square shapes of 3 x 2 meters. These squares were then mixed-and-matched and stitched together to form unique designs. Although this new style was also called leso, the most common cloth for it by that time was white calico from India.

Zanzibar fashion designer Farouque Abdela believes it likely that women who liked this new “linked leso” began using the larger bolts of calico as a base for woodblock-printed patterns made with indigo, henna and other tree dyes. Colorful and affordable, the style caught on. One of its more popular border patterns, white spots on a dark background, resembled the plumage of the noisy, sociable guinea fowl called kanga.

Messages written on kanga today often derive from Swahili methali (proverbs), mafumbo (ambiguous meanings) and misemo (popular sayings) inspired by folklore, riddles, children’s songs and quotes from the Qur’an as well as popular culture.

![<p>Long a form of social media, a kanga communicates through design, color and especially the <em>jina</em> (“message”) that generally appears at the bottom of each <em>mji</em>, or central panel. <em>Left six, clockwise from top left</em>, and translated colloquially, these kanga say: “Don’t see [your beauty or success] as something achieved alone; it’s been made possible by others”; “A person doesn’t have this, but they have that”; “There is no one like mom”; “Better to be poor like me than to be rich like my friend”; “That which loves your heart is medicine”; and “May the best of all blessings come to you.”</p>

<p>Right six, clockwise from top left: “A respectable person is not troubled”; “The one who plays at home is rewarded”; “A liar never takes a break; they’re at work 24/7”; “Let them talk”; “A person is not their color; they are loved for their character”; and “I won’t eat in the darkness for fear of my neighbor (I do what I want!).”</p>](https://prodcms.aramcoworld.com/-/media/aramco-world/articles/2017/kanga-s-woven-voices-images/image-5.jpg)

Long a form of social media, a kanga communicates through design, color and especially the jina (“message”) that generally appears at the bottom of each mji, or central panel. Left six, clockwise from top left, and translated colloquially, these kanga say: “Don’t see [your beauty or success] as something achieved alone; it’s been made possible by others”; “A person doesn’t have this, but they have that”; “There is no one like mom”; “Better to be poor like me than to be rich like my friend”; “That which loves your heart is medicine”; and “May the best of all blessings come to you.”

Right six, clockwise from top left: “A respectable person is not troubled”; “The one who plays at home is rewarded”; “A liar never takes a break; they’re at work 24/7”; “Let them talk”; “A person is not their color; they are loved for their character”; and “I won’t eat in the darkness for fear of my neighbor (I do what I want!).”

Thus kanga, hand-printed on Indian calico, became popular within an increasingly cosmopolitan social scene, as Stone Town became one of the wealthiest cities in all of East Africa. Its docks attracted ships from as far away as the newly independent United States, which in 1837 established a consulate in the region and, by the 1850s, had largely replaced Indian calico with unbleached American cotton referred to as merikani cloth. All the while, kanga continued to gain momentum among Zanzibari women establishing themselves in higher social strata.

By the 1860s, the demand for kanga had grown all along the coast, from Lamu in Kenya to Madagascar. Early designs were inspired by nature, fertility symbols, geometric lines and shapes, as well as fruits and animals. Designs also incorporated cultural influences from the Rajasthani resist-dye technique called bandhani to Omani stripes to the Persian and Kashmiri teardrop-shaped boteh, and to Bantu-inspired motifs like the Siwa horn and the cashew nut. Still, some kanga have retained what became traditional, original color schemes: The kanga ya kisutu, or wedding kanga, for example, has been printed in red, black and white for more than 150 years.

Although women created the first kanga patterns and designs, it didn’t take long before male traders commanded both production and trade. This roughly coincided with the Industrial Revolution, which radically shifted modes of textile production worldwide, and in the early 1900s kanga designers began exporting their designs to India and Europe for mass production, taking advantage of advances in both weaving and printing technologies. Abdela believes that the first machine-printed kanga actually came out of Germany, thanks to Emily Ruete, who was born in Zanzibar as Sayyida Salme, the youngest of Sultan Said bin Sultan’s 36 children. Princess Salme fell in love with her neighbor, Rudolph Heinrich Ruete, a German merchant, and accompanied him to Hamburg, where she lived out her days. Others, he admits, believe the first mass-produced kanga came from England, or perhaps India.

The text messages on kanga began to appear in the early 1900s. Kaderdina Hajee “Abdulla” Essak of Mombasa, Kenya, started the trend when his wife encouraged him to distinguish the kanga he designed by adding a clever inscription. The text, first written in Swahili with Arabic script, added another layer of interest to the kanga, and it was not long until textile merchants followed Abdulla’s lead with their own sayings. When political power shifted from Omani to British administrative rule in the early 20th century, the script switched as well, as the British demanded the use of Roman letters. In the long run, this proved popular, as it wasn’t common for those in lower social strata to read and write their Swahili in Arabic script, and merchants were often asked to read the kanga out loud to help women select the best message.

According to Fatma Soud Nassor, professor of Swahili language and literature at the State University of Zanzibar, kanga messages speak to Swahili joy, love and sorrow. Messages today often derive from Swahili methali (proverbs), mafumbo (ambiguous meanings) and misemo (popular sayings) inspired by folklore, riddles, children’s songs and quotes from the Qur’an as well as popular culture. Still others come out of song lyrics from the coast’s unique Taarab style of music, inspired by Egyptian, Indian and Yemeni rhythms. Rooted in the long history of cultural exchange between Zanzibar and Egypt, it is said to have began in the early 1900s when Sultan Barghash ibn Said invited an Egyptian ensemble to play at the palace in Zanzibar. Male musicians singing in Arabic dominated the form until the 1920s, when the talented and fearless Siti Binti Saad rose up from an impoverished childhood to stun audiences with her Swahili lyrics that ventured into social issues of class, domestic violence and women’s rights.

Mariam Hamdani, director of the Tausi Women’s Taarab group in Zanzibar, carries on Siti Binti Saad’s spirit, and now, as she has reached 70 years old, her kanga collection is a chronicle of her life as a journalist, cultural activist and women’s advocate. Hamdani remembers as a child in the 1950s purchasing kanga with her mother at Darajani Market, where the limited supply meant having to gather around a merchant displaying a sample and submitting a name to a list in the hope of securing one of the limited editions. Today Hamdani treasures hundreds of neatly folded kanga pairs in her closet, each marking a memory or moment, from weddings to funerals, political victories to tender personal experiences.

Some of her kanga carry Taarab songs, like “Mpenzi Nipepe” (“Lover, Cool Me Down”): “Mpenzi nipepee / Nina usingizi nataka kulala / Mpenzi nipoze kwa yako hisani / Na unibembeze niwe na furahani” (“Lover, cool me down / I’m tired and I want to sleep / Lover, heal me with your kindness / And soothe me so I can rejoice”).

Others in her collection feature older designs, styles and names, and some have even become classics, making their way back to the market due to enduring popularity—for example, the kanga ya mkeka (kanga of the woven mat) features bold red, black and white stripes that resemble a traditional mat. The border boasts fat red and black droplets that are echoed as a pair dropped inside a large circle and placed in the kanga’s center. This kanga, printed using 100 percent soft cotton, might be valued for its quality and design alone, but a sharp message takes its intrigue to another level: “Nashangaa kunichukia nimpata kwa juhudi zangu” (“I’m surprised you’re angry with me; I’ve gotten this using my own efforts”).

Pointing to a green and orange kanga with two doves perched on branches facing each other, Hamdani explains that “you can tell from its pattern and its quality, this is a much older design, like this other one here.” Carefully unfolding the kanga, Hamdani says, “This one, this one is also very old. Kanga ya ndege wawili, the kanga of the two birds. Ah! I remember this one from a long time ago. It’s very old, but it’s a design back again on the market. This one will never go out of fashion.” A dizzying mix of polka dots, hearts and flowers that has not changed since its original print, the “Two Birds” kanga carries a tender message of love and guards against jealousy: “Wawili wakipendena adui hana nafasi” (“If two people love one another, enemies don’t have a chance”).

In Hamdani’s collection, threads from the Arab world, too, are woven into her kanga designs. Kanga ya marashi (rosewater kanga) features the symbol of a rosewater sprinkler, which was used to waft aromas of pressed rose oil as far back as the 10th century, and later wove its way from Yemen and Oman to Zanzibar. This particular kanga, in red and white, features a message warning against street gossip that threatens the love between two people: “Wapenzi Hawagombani, pasi na fitina mtaani” (“It’s not the lovers who quarrel, it’s all that street gossip and negativity”). In this context, the rosewater image speaks to the notion it can help heal a lover’s quarrel.

Hamdani also cherishes a red and yellow kanga whose Swahili is in Arabic script. It, too, warns against street gossip: “Sitomwacha mume wangu kwa mngo’ngo mtaani” (“I won’t leave my man for all that street gossip”).

More simply, an Omani kanga with a floral design states, in Arabic, “ward salalah” (“Rose of Salalah”).

And then there’s the love kanga with three simple words written in Arabic: “Layla wa Majnun” (“Layla and Majnun”), which refers to the classic 10th-century love story by poet Nizami Ganjavi.

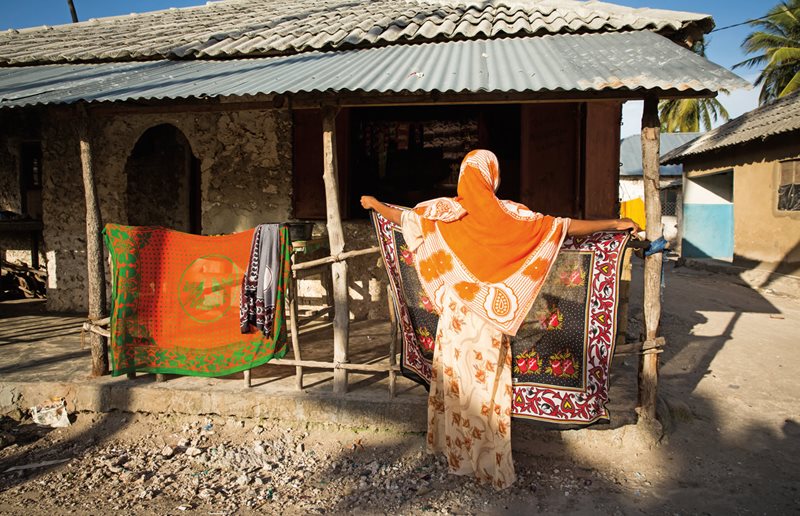

While Hamdani says she no longer wears kanga in the traditional fashion—as both a head covering and wrapped around the waist—she stills wears kanga every day at home, and she follows the tradition of wearing kanga to weddings, funerals and special events. She says that what women throughout Zanzibar and the coast have in common is that whether they live in cosmopolitan Stone Town or in small coastal fishing villages like Bwejuu, they cherish their kanga collections and use the kanga on a daily basis, one way or another.

In the small fishing village of Bwejuu, along Zanzibar’s east coast, elder Mwanahamisi, known as “Bi. Kibao,” asserts that “a Zanzibari woman is not a woman without her kanga.” She goes on to explain, “We wear kanga to cover our hair and around our hips from the time we are small children until the time we die.” Bi. Kibao insists that she loves her kanga for their patterns and designs and doesn’t pay much attention to kanga sayings.

Hidaya, a teacher in Bwejuu and mother of four, agrees. “Many of us choose the kanga because we love their colors and designs. We don’t care too much about the message. Maybe that’s something the younger women are concerned with, but we don’t have time to worry about the message. We love kanga because it is our traditional dress, and as Muslim women, we respect our culture by covering our hair when we’re out.”

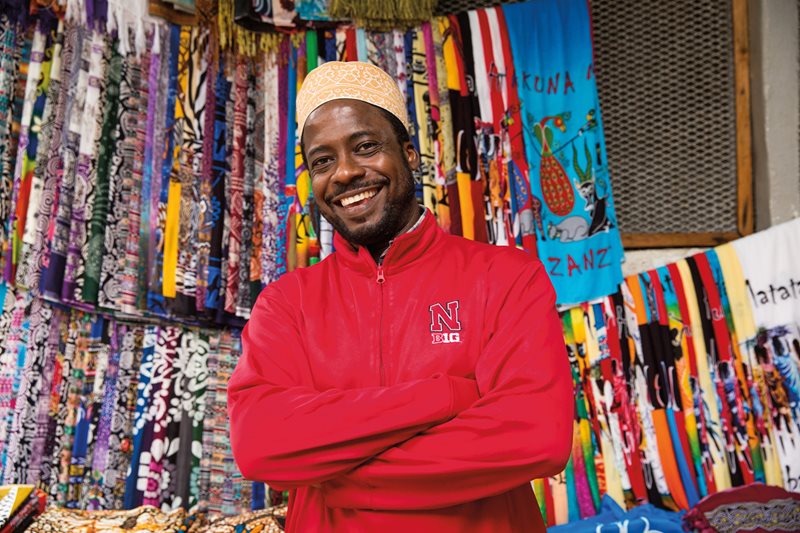

Mohammed Abdallah Moody, a kanga merchant in his 40s, chuckles when he hears that women claim they don’t pay attention to kanga sayings. With hundreds of kanga messages memorized, Moody insists “the kanga is the message.” He supports the common knowledge that Zanzibari women, steeped in gendered traditions of respectability, purchase, wear and exchange the kanga as a unique form of silent communication to relay messages that would not otherwise be socially acceptable.

“When women and even men come to me to purchase a kanga,” he says, “the first thing they look at is the message. Even if the kanga has a nice design, they may not buy it if the message isn’t right. When someone receives a kanga wrapped as a gift, what is the first thing they do when they open it? They read the message! If an elder can’t read the message, the first thing she’ll do is call someone over to read the message aloud.

“The message is everything. It has the power to increase the love and ease the pain of a broken heart. The message can ignite and provoke or soothe and heal.”

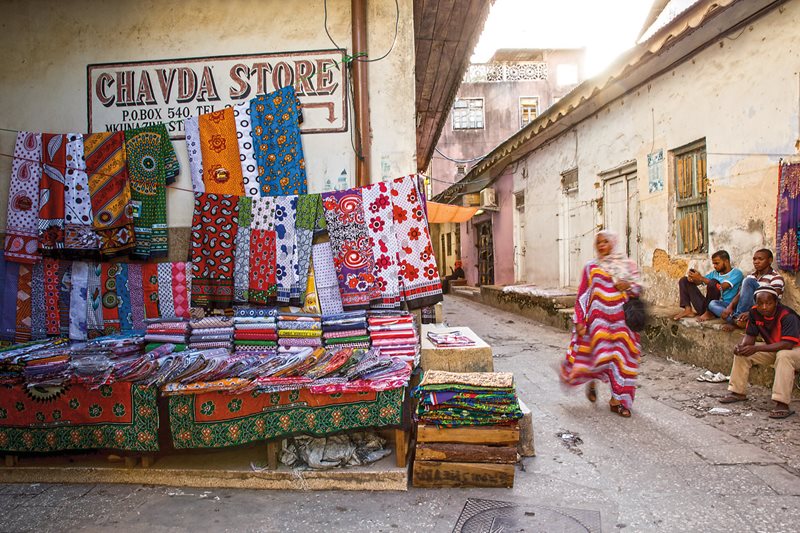

Moody sells his kanga in the textile market on the same street as the shop and showroom of Chavda Textiles, Zanzibar’s largest and oldest kanga dealership, shop and showroom. In the back office crammed with bits of old patterns and hand-drawn design boards, 24-year-old kanga designer Sabrina Ally sits with Chavda’s owners to sketch designs and compose sayings that will appeal to Chavda’s diverse market. Ally, who has worked with Chavda for three years and has designed some of the most popular kanga on the market right now, agrees that a powerful message is crucial to the overall success of the kanga.

“It really hurts my brain to come up with these sayings! My designs have been copied by other kanga dealerships,” Ally says proudly. “For example, I’m the one who wrote the kanga that says, ‘Huna presha, huna sukari, roho mbaya inakukondesha.’” (“You don’t have pressure, or diabetes, your bad spirit has made you skinny.”)

“These days in Zanzibar, there are many different kinds of people, and diversity brings differences of opinion that can sometimes lead to arguments, such as arguments about jealousy. So women these days love the kanga designs that can be exchanged to wake someone up, to surprise them and make them think.”

The kanga, when exchanged or worn for an intended audience, has the power to mediate conflict. Recently Ally composed the popular phrase, “Mimi ni mwangana sina muda wa kugombana” (“I am a peacemaker; I don’t have time to fight”). This came to her, she says, while she was at home thinking about the way Zanzibari women tend to handle discord. She explains, “Women usually have their fights, but they fight in secret. They don’t want others to know that there’s any issue or concern. Whether it’s about a man or a misunderstanding at work, women use kanga to make sure their position is heard while still maintaining their integrity and self-respect.” There is even a phrase for this, she adds: “Kupiga kanga” means “to hit the kanga,” by answering one kanga with another, communicating messages back and forth until the conflict is played out.

It’s all good business, too. Chavda Textiles often provides wholesale kanga to other kanga dealers for about 4,400 shillings, or about us $2.20 each. The firm sends up to 30 new designs to its factory in Mumbai each month and, at any given time, a kanga seller stocks 50 new designs and 50 designs from the past and an assortment of messages from blessings, prayers and wishes to the bolder ones. Governments, politicians and even nongovernmental organizations have also used the kanga as a messaging platform as far back as World War ii, when a commemorative kanga featuring industrial machines and boats proclaimed: “Ahsante bwana Churchill” (“Thanks Boss [Winston] Churchill”).

In contrast with Zanzibar, where women prefer very thin, light cotton kanga with Swahili proverbs, riddles and sayings, on the Tanzanian mainland women prefer kanga nztio, which is produced with heavier cotton featuring darker, deeper colors and messages related to faith and religion. On Uhuru Street in Tanzania’s former capital, Dar Es Salaam, kanga dealerships with names like Morogoro, Nida, Urafiki and Karibu Textiles all sell out of their showrooms the heavy kanga pairs for 7,000 shillings a pair, or about us $3.50. Fadhilia, a kanga seller on Uhuru Street, insists that “men and women both love to buy kanga. There’s not a man in Tanzania who has not purchased a kanga for his mother, grandmother or wife at least once in his life.”

Back in her office in the Swahili department at the State University of Zanzibar, professor Fatma Soud Nassor tears up as she recalls the day her mother passed away. “You know, we use the kanga to pray. For my mother’s funeral, her sisters looked through her collection to select a kanga to wash and wrap her body for burial…. I cried a lot to see my mother in this kanga because on it was written, ‘Nimerhidikwa na hali yangu’ [(‘I’ve been satisfied with my situation’)]. When I passed her body, what I saw was the name of her kanga, and it carried a huge and meaningful message to me, and so I wept.”

From the shores of history, echoing desires, dreams, worries, obsessions and passions of the Swahili coast, the kanga call out. From the newborn wrapped in kanga wisdom in her mother’s arms, to an anxious bride receiving her bridal kanga from her husband’s family, to an elder who rests in peace wrapped in kanga, its meaning and messages hazife—will not die.

About the Author

Amanda Leigh Lichtenstein

Amanda Leigh Lichtenstein is a poet, writer, editor, and educator who splits her time between Chicago, IL (USA) and Stone Town, Zanzibar. Her essays on arts, culture, and education appear in Selamta, Contrary Magazine, Global Voices, Teachers & Writers, Mambo Magazine and Addis Rumble, among others. She currently edits for Global Voices Online and is working on a book of essays about Zanzibar. Follow her on Twitter @travelfarnow or visit her website: travelfarnow.com.

Samantha Reinders

Samantha Reinders (samreinders.com; @samreinders) is an award-winning photographer, book editor, multimedia producer and workshop leader based in Cape Town, South Africa. She holds a master’s degree in visual communication from Ohio University, and her work has been published in Time, Vogue, The New York Times and more.

You may also be interested in...

Flavors: Cracked Wheat and Tomato Kibbeh

Food

Sitting on the beach with my feet in the sand, listening to sounds of Lebanese pop music drifting through the air, watching children play in the water, eating simply cooked line-caught fish with this beautiful vegetarian tomato kibbeh. I don’t know how you could top it.

Revival Looms

Arts

In Georgia Borchalo rugs are making a tentative comeback amid growing recognition of the uniqueness of ethnic Azerbaijani weaving. There’s hope that this tradition can be saved.

Silk Roads Exhibition Invites Viewers on Journeys of People, Objects and Ideas

Arts

An evocative soundscape envelops visitors as they enter the Silk Roads exhibition at the British Museum in London. Huge screens along one wall project images of landscapes and oceans, while visitors are invited to experience the scents of balsam, musk and incense contained in boxes around the exhibition.