Marseille’s Migrant Cuisine

- Food

Written by Tristan Rutherford

Photographs and video by Rebecca Marshall

THE MODERNIST BOX OF MARSEILLE’S MUSEUM OF EUROPEAN AND MEDITERRANEAN CIVILIZATIONS (mucem) SITS ASTRIDE THE MOUTH OF THE CITY’S OLD PORT, NOT FAR FROM THE PLACE GREEK SAILORS SET UP A TRADING POST 2,600 YEARS AGO. THE CITY MINTED ITS OWN MONEY THEN, AND IT INTRODUCED OLIVE TREES FROM LANDS AROUND THE AEGEAN AND GRAPEVINES FROM AROUND THE ADRIATIC.

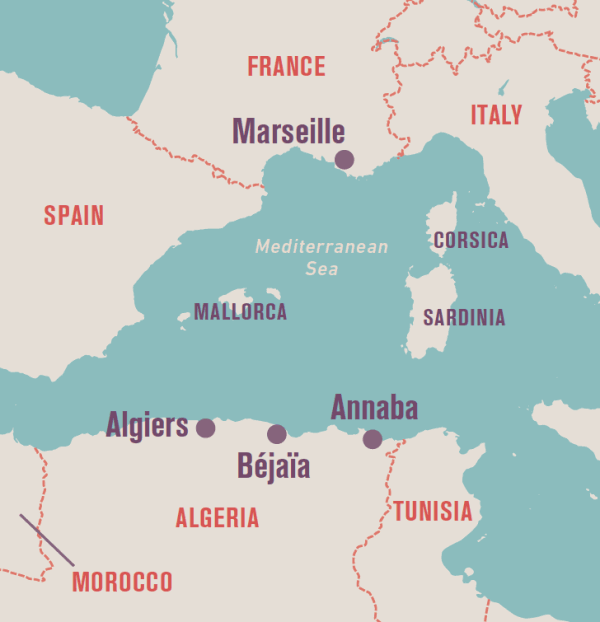

Atop the museum, Emmanuel Perrodin, Marseille’s leading culinary historian, sips black coffee. The panorama over France’s third-largest city takes in the seemingly limitless sea, ramparts of 17th-century forts and a few cereal silos from the 1920s. Passenger ferries chug to and from the modern successors of the Roman trading ports of Béjaïa and Annaba in Algeria, as well as the Mediterranean islands of Corsica and Sardinia.

“Our city has a particular geography,” says Perrodin. “My favorite Marseillais saying is, ‘First you have the sea, then the city, and beyond that is another country called France.’”

Perrodin explains that, like Alexandria, Egypt, Marseille was a “lighthouse city.” A key commercial gateway, a port city that has attracted all comers, it thrived as a polyglot trading colony while Paris was still just a village. Believed to have been established around 600 bce by Greeks from Phocaea (now Foca) on the west coast of Turkey, the city’s more recent arrivals have included Russians, Armenians, and Berbers from Algeria—among the latter the parents of France’s greatest soccer player, Marseille-born Zinedine Zidane. Most recently, in the decades following independence, families from former French colonies have come here, along with many more.

With human traffic came food, and with food came recipes. Dates entered Europe here, says Perrodin, and “arguably” tomatoes and bananas.

“Safeguarding your favorite foods is perhaps the most important cultural act,” he says. “Three times per day you reinforce your cultural identity in your heart—and your stomach.” Most curiously of all, the recipes that came first to Marseille—take North African merguez lamb sausage, for example—would now be eaten by a Cypriot French family in Paris, or by a Congolese French family in Normandy.

“Our national dish is couscous. Tajine [from North Africa] is served in French schools. If you imagine French cuisine as a tree, the leaves are in Paris, but the roots reside in Marseille.”

Seeds of the city’s culinary evolution can be found a few blocks north in the district of Noailles. On the corner of Rue d’Aubagne, one can see a Tunisian leblebi soup store. An Ivorian snack bar sells alocco fish with grilled plantain—and nearby is Marseille’s last remaining ricotta cheese creamery. A young woman with her smartphone tucked into the elastic of her headscarf continues a phone conversation as she shops for fruit. A young boy warns “yalla!” as he weaves his bike down the street, fishing rod in one hand. The roars of scooters and the calls of hawkers render the street a maelstrom of multiculturalism, a 21st-century Babel where one could conceivably order lunch in English, Spanish, Arabic or French.

Such telegenic scenes are backed up by tales of economic necessity. The story of 37-year-old Jiji Azizi, who manages the spice emporium La Palme d’Or, also on Rue d’Aubagne, is a mirror of migration into Marseille. “No one of my generation consciously moved here. We were born here instead.”

In the 1950s and 1960s, she says, the Mediterranean was a more open sea. Azizi’s father was one of seven brothers and sisters sharing a home in Africa’s northernmost city, the Tunisian port of Bizerte. “In that position you just moved to France,” Azizi says. Fortunately, his fragrant store was a success. “Armenians, Algerians, Greeks—we all eat the same halvah, dolma and all the rest.” Azizi proudly claims she is Marseillaise, before being of Tunisian roots or French citizenship. “Perhaps it’s like Italians in New York. Despite being there for one century, some people are Sicilian first, then American second.”

Such stories are commonplace. Bêline Sy arrived in Marseille aged 18 months in 1979. Her parents lived in Vietnam’s southern colonial resort of Dalat, a leafy town that, once part of French Cochinchina, was base for soldiers of Arabian and African origins serving in the French Army. “When I return there, I get laughed at because I speak Vietnamese with a Marseillaise accent,” she says. In the mid-1960s waves of American soldiers came to her family’s town. A decade later Sy’s parents fled from communist authorities with their nine children.

The family’s Marseille fruit stall grew to become Tam-Ky, now the area’s largest international food emporium, on the bustling Rue Halle Delacroix. Sy’s checkout now rings orders of Mauritian piments, Madagascan kumbawa citrus and Indonesian pepper to patrons from Senegal, Cambodia, Mali and much of the rest of the world. A final novelty is the curious circumflex above Sy’s forename, Bêline. “In Vietnam we wear conical hats,” she explains, “so I put one on the ê of my name. When you move to a new country, you can do anything you want.”

Other recently settled residents are plying their wares through France, like Mediterranean traders of two and half millennia before. Around the corner from Azizi and Sy, down past a sweet-smelling shop selling mahjouba—crepes, North African-style—another with flipflops and a couple of halal butchers, Joseph Azzi set up his Le Cedre du Liban (Cedar of Lebanon) bakery in 1995. “Lebanese are everywhere,” says Azzi. “Saudi, Africa, London, Brazil.”

He walks past crates of pomegranate molasses to fire up his flatbread machine. With a whirr and a clunk, the timeless, round Arab loaves bake and then cool along a 15-meter conveyor that snakes underneath the flour-dusted ceiling. Stacks of flatbreads are sealed into plastic bags before being couriered along former Roman roads—now fast autoroutes—to Nice in the east and Béziers in the west. The fact they are eaten with restaurant falafil or supermarket couscous is testament to Marseille’s status as France’s ville carre-four—its crossroads city.

Yet now, as it has been for centuries, arrival also often means struggle. Some of Marseille’s most recent newcomers arrive with more recipes than official papers or networks of helpful friends. Some learn quickly they can rely on Fatima Rhazi, a grandmother originally from Morocco who acts as a kind of great aunt to Marseille’s migrant women. Her organization, Femmes d’Ici et d’Ailleurs Marseille (Marseille Women from Here and Elsewhere) was formed in 1994 to foster dialogue through food.

“Some new ladies are timid for all sorts of reasons, but when cooking in our communal kitchen they open up. Believe me, women have the same problems all over the world,” says Rhazi. By sharing recipes, they learn food preparation, hygiene and language skills useful for both household management and employment. And it works: 1,257 previously unemployed people who have passed through Rhazi’s workshop are now in paid work.

Rhazi’s backstreet office-kitchen includes a 500-book library with (titles such as La Cuisine du Monde and Délices du Maroc) that serves as a recipe vault for almost every Mediterranean, Arabic and African dish. Some hand-me-down methods remain handwritten in Arabic. Others reside on the hard drive of the association’s creaking computer. “I’m from Morocco, which has three couscous recipes, but our association regularly makes 11 different varieties,” Rhazi says.

This culinary archive at Femmes d’Ici et d’Ailleurs Marseille is important also because, as an entirely self-financed organization, it is a database that helps support large-scale catering for weddings, birthdays and other events, all of which help pay for the organization’s many services. When mucem hosts 300 guests for an exhibition opening, they often call Rhazi first. At such times, she then calls upon volunteers who hail anywhere from the steppes of Mongolia to the golden sands of Ghana to work the 20 gargantuan cooking pots and countless tajines in the adjoining kitchen. “Customers can also dine in the upstairs restaurant. We call our cuisine oriental. The term is meaningless,” Rhazi says with a smile, “but it pushes all the right buttons.” Dishes can include light-as-air black-eyed pea accara fritters from Senegal and herbed Moroccan chicken with a lemon confit sauce.

Rhazi’s own early travels influenced her palate, too. Raised a few miles from the Algerian border in Oujda, around four decades ago she was Morocco’s 200-meter and 400-meter women’s running champion, and this took her to competitions throughout the Mediterranean. She speaks, for example, about a Sephardi dish from the Tunisian island of Djerba called skhina. For religious reasons, Tunisia’s Jewish community required a Saturday feast but could not prepare food on the Friday Sabbath. So the recipe of eggs, rice, spices and meat is slowcooked overnight into a state of delicious caramelization.

Recognition of Rhazi’s work, and by extension Marseille’s culinary mélange, came in 2009 by presidential decree. France’s then-President Nicolas Sarkozy, himself of Greek and Hungarian parentage, together with Justice Minister Rachida Dati, who is the second of 12 children of Moroccan and Algerian heritage, visited Femmes d’Ici et d’Ailleurs Marseille.

To Rhazi’s consternation, Sarkozy and Dati did not give her a check: Instead they knighted her, declaring her chevalier de la légion d‘honneur, the nation’s highest order of merit.

“I am a knight without a horse,” she jokes. Then with her characteristic self-confidence, she asked France’s president to assist 17 migrant families who were struggling without the correct paperwork. “I’m tough because I have six brothers. That’s why I fight for women.”

At a gourmet level, it is migrant and migrant-fusion recipes that can be found all across Marseille. The restaurant atop mucem serves a prime example with its culinary deconstruction of the famed city dish bouillabaisse, a “poor man’s stew” that infuses imported saffron and tomatoes with local rockfish. Then there are hipster-Maghreb patisseries such as MinaKouk that create avant-garde pigeon pastilla as well as Franco-Arabian macarons. Marseille tourism bosses sell the city by inviting food bloggers from across France, North America and Asia. An Instagram generation strolls the street snapping Tunisian favorites like wafer-thin, oozy-egg brick à l’œuf, or Turkish mantı, a ravioli topped with creamy yogurt. Marseille chefs of every background are grafting contemporary takes onto a culinary movement that first set sail in Aegean triremes 2,600 years ago.

Nowhere is this trend more compelling than at AM par Alexandre Mazzia, a restaurant a block from the Stade Vélodrome, home of the top-ranked soccer squad Olympique de Marseille. Here Michelin-starred chef Alexandre Mazzia has turned Marseille’s migrant flavors, including Turkish sumac and Nigerian manioc, into world-beating fare. “My own story is typical of Marseille,” says Mazzia. His paternal grandfather was an Italian saxophonist who made a mean saffron risotto, while his mother’s father was a Corsican fisherman. “Therefore, it was psychologically easy for my Marseille family to emigrate to Congo in the 1970s.” There, Mazzia’s father took a job selecting hardwood timber for global export from the rainforest of Mayombe.

Mazzia was born in 1976 in Pointe-Noire in the Republic of Congo. Like Marseillais of other backgrounds, he grew up eating saka-saka, a pesto made of manioc, fish and palm oil. “When I came to live in France at age 15, I felt at home in Marseille,” he says. “Indeed, my dishes are a metaphor for the influences every resident transmits.” And what fusions they are: Algae chips dotted with sweet-potato jellies, topped with bottarga roe; langoustines wrapped in balls of tapioca, a West African staple, that pop in the mouth like caviar and a frozen Franco-Maghreb gem of raspberry and harisa, whose flavor serenades like Mediterranean waves and then sears like the Sahara.

It’s a long way from beef bourguignon. As Mazzia says, “People from Paris now come to me. The restaurant is booked solid for the next two months.”

Mazzia now works on culinary projects across the city including private after-hours access to the Musée Cantini gallery of fine art, where paintings like Paul Signac’s “Entrée du Port de Marseille” show steamships delivering goods from across the globe. Mazzia takes inspiration from these canvases’ watery rhythms to create dishes for intelligentsia-based foodways road-tested for centuries by migrants.

“The staff at my restaurant l’AM come from 11 countries, from Comoros to Korea,” he says. That is as many nationalities as fielded by the current Olympique de Marseille soccer team, which has won the Coupe de France trophy a record 10 times.

“The richness of Marseille is its mix of cultures,” he says. “Together we win.”

About the Author

Rebecca Marshall

Rebecca Marshall is a British editorial photographer based in the south of France. A core member of German photo agency Laif and Global Assignment by Getty Images, she is commissioned regularly by the New York Times, Sunday Times Magazine, Stern and Der Spiegel

Tristan Rutherford

Tristan Rutherford is a 7-time award-winning journalist. His writing appears in The Sunday Times and the Atlantic.

You may also be interested in...

Histories on a Plate-Reflections on Food and Migration

Food

History

75th Anniversary Food

Food

From the ancient world to modern main courses, AramcoWorld’s vivid cover stories highlighting diverse dishes offer readers an opportunity to dig into a variety of recipes and how culinary traditions defined cultures.

Tastes of Azerbaijan

Food

Azerbaijan has sat at a crossroads of Eastern Europe, the Middle East and Western Asia for centuries as a Silk Road hub and a gateway that empires routinely fought to control. That intersection also has manifested itself in the nation’s food—a complex and enticing stew of Turkic, Persian, Eastern European and other regional influences. This food diary explores the unique cuisines of each region.