“I used to see them in the 1970s when I’d go swimming as a little girl. l can still see one of them in my mind’s eye. It was low tide, so you could walk far out. It was sandy with lots of green grass in the water. Then right at the edge where the water dipped down into the deep again, I jumped in. And there was this big thing under the water—it was slow and fat and had big sad eyes. I swam up to it—and it to me—and we looked at each other. Then I remember coming up for air and my mother shouting, ‘Giselle, Giselle, come here,’ from the shore where she had waded in after me. I went back under, and it was already gone. But I sat there for a long time playing with the seahorses thinking it would come back.”

The other day when I mentioned to my friend Giselle, who had spent part of her childhood along the east coast of Saudi Arabia, that I was working on a story about the dugong, I expected her to say “the du-what?” like most people. (Even me, until I started reading about them.) Instead, she surprised me with her beautiful recollection from her childhood of an unforgettably gentle, eye-to-eye encounter.

It is a story, it turns out, that people have told in various ways for thousands of years. Dugongs likely inspired the original mermaid tales. Aboriginal rock artists in Western Australia drew a dugong as part of a “great fish chase” some 8,000 years ago. Stories specifically mentioning mermaids began circulating in the South Pacific and Indian Ocean about 3,000 years ago. Assyrians, whose empire was based far inland in what is today Iraq, wrote about mermaids. Italian explorer Christopher Columbus recorded three mermaids sighted near what is now the Dominican Republic. The most famous collection of Middle Eastern folk tales, Alf layla wa layla, (One Thousand and One Nights) mentions mermaids at least twice.

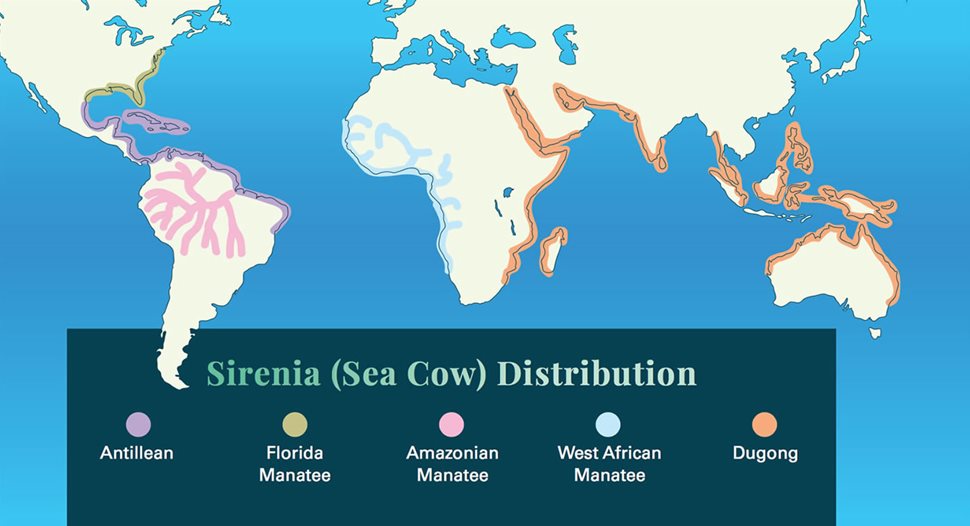

To most people today—even those living along the warm-water coasts of the Indian and Pacific oceans and the Red Sea—mythical mermaids feel more familiar than, for example, the actual 5,000 to 6,000 dugongs that inhabit the waters off the coast of Abu Dhabi alone. But in Abu Dhabi, as everywhere else dugongs live, as the human population has surged, dugongs have dwindled. The reasons are many: coastal development, boats and warming waters are a few, and all of these affect the dugong’s food: seagrass. Dugongs are also known in Arabic as baqarah al-bahr (sea cow), because they spend all day in shallow waters grazing on the seagrass.

A two-hour boat trip takes me from Abu Dhabi to meet people who once lived and worked among dugongs. Tiny Delma Island was once a key port for both fishing and pearling. Although fishing is no longer a necessity and pearling long defunct, the most common expression here is “ al-bahr kulshee”—“the sea is everything.” Retired fishermen gather every morning to play dominos in a dusty café called Angry Birds. It overlooks the harbor, where families still have their wooden dhows anchored. The fishermen and sailors remember the marine mammal as docile and weighing 250 to 400 kilograms.

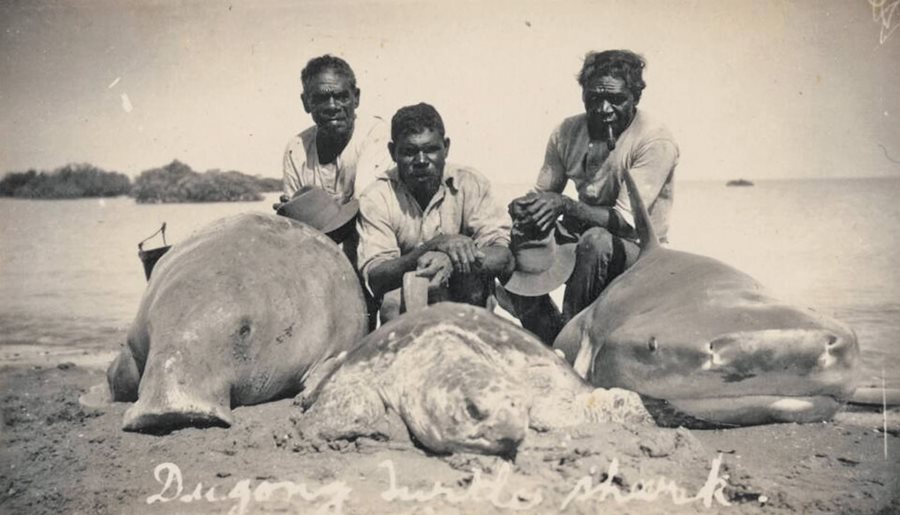

Then someone says, “We used to eat them.” One dugong, he explains, is literally big enough to feed a village.

“But we are not allowed to catch them anymore,” another fisherman emphasizes. Like most countries now, the United Arab Emirates has banned the capture of dugongs, which the International Union for the Conservation of Nature lists as “vulnerable,” depending on location.

While the swish of a dugong’s tail could sync with any Hollywood mermaid, and dugongs go about with what appears to be a permanent smile, dugong eyes are small—nothing like the ones Disney gave Ariel. And its ears tuck, unglamorously, inside. Nonetheless, it hears well, which compensates for poor eyesight.

“Sailors would be out to sea for long periods of time, and given that, the dugongs probably reminded them of women, particularly if they came across them breastfeeding,” says Helene Marsh, Distinguished Professor of Environmental Science and Dean of Graduate Research at James Cook University in Australia, home of the largest dugong population.

Although dugongs are shy, they have been personified because they sometimes (although increasingly rarely) enjoy interacting with humans, much like dolphins. In the low-lying archipelago nation of Vanuatu, in the South Pacific, where the dugong is the largest resident mammal, tourists visiting the island of Epie used to go out on boats to wait for Pontas, a dugong who would come up to the boats to say hello—until one day, after 10 years, he didn’t. Veterinarian Christina Shaw, who is also founder and ceo of the Vanuatu Environmental Science Society, says that Pontas may have perished in a fishing net, a cyclone or simply lived out his estimated 70-year lifespan.

Shaw has had her own encounters diving with dugongs. “Sometimes they stay around, and sometimes they will just stay for a minute or two and then swim off.” Sometimes this is just to breathe, she points out, as dugongs need to surface every three to 12 minutes. “It’s just very unique to have interactions with a wild animal that isn’t afraid of humans.”

In other places, encounters have stoked other legends and customs. In the Lau Lagoon region of the Solomon Islands, in Oceania, journalist Bira’au Wilson Saeni recently recorded a tribal chief telling the tale of a woman who jumped into the sea and became a dugong to escape her evil mother-in-law. The chief told him this is why his tribes do not eat dugongs.

Chelcia Gomese, who facilitates the dugong conservation project at WorldFish in the Solomon Islands adds, “We are split along two lines. While some tribes used to eat dugongs, in the village of Naro, the dugong is sacred because the tribe there believes it is descended from dugongs.”

Across the Indian Ocean, Mozambique’s Bazaruto Island has East Africa’s only remaining viable dugong population. Here Alima Taju is mapping the population for her doctorate in conservation biology. She has discovered that many people here too do not eat dugongs because of their resemblance to women. (And in northern Mozambique, with a Muslim population, people do not eat it because there it is called “sea pig.”)

“It can even be bad luck to catch one in a fishing net in Bazaruto,” Taju explains. “People used to believe catching a dugong cursed you as a fisherman. In order to be able to catch fish again, and thus make a living, a fisherman had to undergo a ceremony performed by a witch doctor.”

The names sea cow and sea pig refer to the less elegant side of the dugong—the way it eats. Dugongs are picky. That green seagrass that surrounded Giselle may have been her childhood dugong’s lunch, but not all the seagrass—only the soft, new leaves that don’t upset its tummy. Nonetheless, almost like a vacuum cleaner, a dugong can munch through 30 kilos of it a day.

But there is now, according to the Abu Dhabi-based Dugong and Seagrass Conservation Project (dscp), 29 percent less seagrass than decades ago. Every year, the world loses 110 square kilometers of it a year—an alarming rate of decline roughly equivalent to that of tropical forests.

Around 40 countries are known still to have dugong populations, and the dscp is now working with eight along the Indian Ocean and the South Pacific to create community-based programs that support seagrass, dugongs and humans.

Among them is Vanuatu, where Shaw and her team are writing the world’s first full guide to conserving the dugong. In 2015 a cyclone devastated Vanuatu’s seagrass beds, and thus, minimizing both natural as well as human-induced decline is important.

So are sustainable tourism practices. Shaw cites one such example in which fishermen take tourists on outrigger canoes to the dugong conservation area. Each tour guide then brings back money to be divided within a community pool. This system discourages competition among tour guides, which is often a cause of too much human impact in an area.

“The dugongs know that we use them as an attraction, so they will put their head out when they see the canoe,” says Program Director Joseph Soksok. “We want more dugongs. There are some places where we used to have seagrass. These areas used to look brown because of the sea grass, but now when we go there, we only see white, sandy beach,” he continues. “The dugongs don’t have enough food. If we want more dugongs, we need to figure out a way to increase the seagrass.”

In the Solomon Islands, where 30 percent of the population depends on fishing for income, Gomese, the WorldFish conservationist, works with programs that help this nation of 1,000 islands find paths out of poverty and environmental degradation. She estimates that only half the islands’ citizens know anything about dugongs, but seagrass monitoring programs are helping change this.

For example, on Tetpere Island, a marine protected area since 2003, scientists have trained women to record seagrass beds and how they change from place to place over time. This helps the community understand which spots are at highest risk.

In Mozambique, the civil war that lasted from 1977 to 1992 displaced many people from the interior to the coast. The new arrivals came without generations of sustainable fishing practices passed down to them, and they would catch the dugong for food. “They had different ways of respecting nature, and so they overfished,” says Taju. “But I would say those who came in the 1970s are now local, and they understand proper fishing better now. We also have programs in schools to train teachers to educate students about proper fishing and dugong conservation,” she adds. “Migrant fishermen are the problem today. They stay, for example, for two weeks—and they don’t come from a specific place—and they will catch dugongs because they don’t have the respect for them that coastal people do.”

She explains that people will go to jail and pay a fine if they intentionally catch a dugong, but if they accidentally kill one, they only pay the fine. Ultimately, she says, it’s a code of conduct. Dugong tourism plays an increasing economic role in Bazaruto too: One of the few places for tourists to stay is named Dugong Beach Lodge.

The Torres Straits in northern Australia is the only place dugongs can be hunted legally—and only by residents.

There is still one place in the world where dugongs can be hunted legally—and then only with a spear: the Torres Straits, in northern Australia near Papua New Guinea, a remote area inhabited by a population of 4,500. This is the dugong capital of the world, and here dugongs are both food and family. Along with the green turtles of the area, dugongs have been a major source of protein for some 4,000 years. Dugongs are also embedded in the culture, appearing on everything from pottery to T-shirts. Since the 1970s, the islanders have become known in art circles for their prints and linocuts that often tell the cultural history of the people. When an exhibition went on tour to various countries 10 years ago, it was called “Gelan Nguzu Kazi” (“Dugong My Son”).

For many years scientists worried that the dugongs in the Torres Straits were at risk of overhunting, but 30 years of research by Marsh demonstrated the opposite. “We think the number is around 80,000,” she says, which far exceeds the 12,000 she and other scientists had estimated before newer technology allowed them to better assess life deeper underwater.

But Marsh does not think that the Torres Strait balance can be achieved anywhere else, and captive breeding, she adds, does not work for dugongs. The problem is partly size, but mostly “taking care of a suckling dugong is a 24-hour job, like looking after a human baby.”

Back in Abu Dhabi, standing on a seemingly empty beach on Hudayriat Island, just a few kilometers away from the city center, archeologist Mark Beech points down at what he calls a “dugong midden” because of the large number of dugong bones scattered under the sand and associated with pottery dating from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. These remains, he explains, are proof of a village involved in fishing and pearling.

Farther from the city center, on Marawah Island, Beech has excavated the region’s oldest-known dugong bones, which date back almost 8,000 years. “Dugong bones found within different rooms at the settlement mean it made a valuable contribution to their diet,” he says. Bedouin, he adds, used dugong hide for sandals. “It was also used to make soldier’s helmets, shields and other protective gear by populations of the Red Sea and North East Africa. The oil from dugongs had many uses,” he adds, “including for cooking, conditioning wooden boats, fuel for lamps and medicine. It was even considered by some to be an aphrodisiac, and thus it was traded to many countries.” Beech also discovered dugong bones on some of the gravesites of the island, which locals explained indicated the deceased was a dugong hunter.

“We need to conserve cultures as well as species,” says Marsh, explaining that dugong conservation connects to other global efforts to conserve species, traditions and heritages. Then, more children might get the chance to meet these real-life mermaids, eye to eye.

You may also be interested in...

The World’s First Oils

History

Science & Nature

Pressed, extracted or distilled from any of hundreds of plants, pure “essential” oils are not just a rising multibillion-dollar global industry: They are among the world’s oldest organic wellness products, now available almost everywhere.

Pistachios' History of Graft

Food

Science & Nature

Stimulated most recently by nutrition studies and marketing, pistachios are more available worldwide than ever. But today’s efforts are possible only thanks to patient bioengineering some 3,000 years ago.

Ingenuity And Innovations 1 - Kohl Eyeliner: More Than Meets the Eye

History

Arts

Science & Nature

The black eyeliner known widely today as kohl was used much by both men and women in Egypt from around 2000 BCE—and not just for beauty or to invoke the the god Horus. It turns out kohl was also good for the health of the eyes, and the cosmetic’s manufacture relied on the world’s first known example of “wet chemistry”—the use of water to induce chemical reactions.