The World’s First Oils

- History

- Science & Nature

- Health

Written and photographed by Ken Chitwood

Petite, iridescent bottles and bulk household products filled with or using pungent, concentrated, natural “essential” oils have become so common on retail shelves and websites that they are almost unremarkable features of the modern consumer landscape. Essential oils are increasingly part of a lifestyle—like yoga or organic foods—that appeals to young and old, men and women. As recently as a decade ago, anything infused with the sweet-smelling fragrances of essential oils may have been associated more with patchouli-redolent bohemians. But today, buying, wearing and diffusing essential oils is nearly as commonplace as the online shopping that has helped popularize them.

According to market research firm Statista, the global market value for essential oils is projected to reach $27 billion by 2022, based on estimates done before the covid-19 outbreak. The market in the us alone is currently worth $4 billion, and essential oils now help scent perfumes, soaps, cosmetics, flavorings, cleaning products, lotions, candles, aromatherapy products and even aerosols such as “Sleep Serenity Moonlit Lavender,” a “bedroom mist” by Febreze. Mixed with jujube bark extract, they are also found in Sephora’s Christophe Robin shampoos. The list could go on.

The growing popularity of essential oils is the latest chapter in a history of use and fascination that dates back more than 3,000 years. Used through the centuries for staying healthy, worshipping, sleeping well, de-stressing, making dinner and just smelling nice, what were known in classical Greece and Rome as “odiferous oils and ointments of the Orient”—as the late organic chemist A. J. Haagen-Smit alliterated in 1961—have wafted west. Along the way they have infused not only scents but also dollars into major retail chains such as Carrefour and Walmart, as well as independent specialty companies, from boutiques to multilevel marketers that now rank nearly alongside Avon and Mary Kay Cosmetics. The passage of essential oils from East to West is a story of encounter and exchange, invention and inquiry, trade and transcendence that continues today.

Bethany Brubaker, a mother of three from Los Angeles, says she attended a class on essential oils in 2013 when she was pregnant with her second child. The class was sponsored by Utah-based doTERRA, one of the largest essential oils companies in the world. As of 2015 doTerra had surpassed $1 billion in sales.

“I was desperate for natural remedies to help me combat migraines induced by a prescription of mine,” she says, adding that she also was seeking to provide a healthy environment for her children and natural ways to relieve regular aches and pains.

In oils, Brubaker says, she found not only a remedy for her migraines but also relief for her daughter’s allergies and “answers for joint pain and natural ways to support my little family through so many situations.”

“It’s not surprising to me that more and more people are using essential oils,” says Lisa Bollinger, a homemaker in Michigan who sells oils for one of doTerra’s competitors, Young Living. Founded in 1994, Young Living imports many of its oils from the Middle East and Asia, especially Oman, the Philippines and China, and it sells mainly across Europe and North America.

“They’re gaining more positive attention,” says Bollinger. “People have incredible testimonies of how they have helped them overcome huge sicknesses and health issues.”

The us Food and Drug Administration (fda), while not contesting the appeal of oils for their scents of beauty, has cast a skeptical eye on medicinal claims that remain debated among medical and pharmaceutical communities.

Bollinger invokes history.

“It’s what we used to use before pharmaceuticals took over,” she says, “and if that’s what we always used for centuries and it works, we should keep doing it.”

In all their varieties of scent, origin and use, essential oils all have this in common: They are naturally distilled by either steam or cold pressure from plants, and this includes combinations of seeds, stems, roots, leaves and blossoms.

Trygve Harris, originally from California, now lives in Oman, home to Boswellia sacra, the frankincense tree whose resin and oil once brought centuries of riches to the southern Arabian Peninsula. Founder of New York-based essential oils boutique Enfleurage, Harris says her distillery in Oman’s capital of Muscat allows local shoppers to experience the natural method of making and using essential oils.

“When you buy an essential oil, you are buying beauty, serenity, posterity,” she says, noting that in particular, Frank—that is her affectionate nickname for it— allows buyers to connect with Oman—its history, its people, its geography, its national soul. “That’s why people are drawn to it,” she says. “That’s why people come on pilgrimage to Dhofar. They go out and sit with the trees.”

It was only after traveling through the Middle East, Southeast Asia and Africa and studying aromatherapy in Australia, Harris says, that she decided to launch Enfleurage in 1997 in New York’s SoHo. In her company’s early years, Harris sold a variety of wellness products and essential oils, her own and those made by others. She found that frankincense in particular, already among the best known among a family of oils that include lavender, cedar, eucalyptus, orange, peppermint and dozens of others—offers many uses in each of its drops and earns many claims of wellness among those who use it. While each oil offers unique benefits, Harris says that over time, she began to lean more passionately toward Frank—so much so that she now even offers frankincense ice cream.

“When people ask me, ‘What can this oil do for me?’ I am at a loss at what to say!” she says, because to view them in only utilitarian ways can overlook the sensual pleasure of their delightful, evocative scents which are, well, their essences. “I try to help them recognize the beauty of the oils themselves.”

“Miraculous,” Harris calls them, noting that like many other essential-oil enthusiasts, on a typical day she might use oils for sleep, headache, a burn or a cold.

This year, as the world faces the pandemic of covid-19, such wellness concerns and interest in the purported healing properties of oils have sharply increased. Some representatives of Young Living and doTERRA have been active on social media claiming that blends containing clove, cinnamon bark, eucalyptus, rosemary and lemon—all traditional medicinal plants—could help “boost immune and respiratory function” and that a range of oils could help “balance emotions” and “keep your family healthy and strong” in a time of stress and uncertainty.

And looking back, it turns out that if one follows the history of essential oils and their journeys, uses and prestige as they traveled west, it is apparent they have been deemed valuable—indeed essential—elements and accoutrements of comfort, wellness and belief in their efficacy.

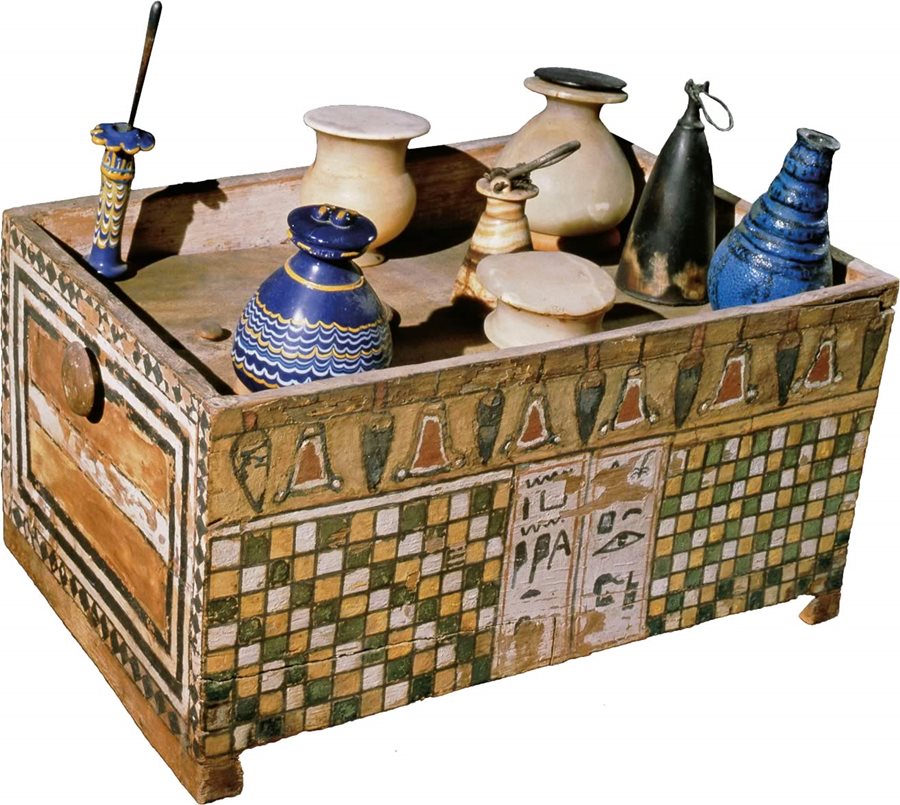

The earliest records of essential oils point to around 3000 bce when botanists and physicians in Egypt, China and India were using essences and oils for perfumes and medicines. Actual human practice, however, probably began far, far earlier. When oils crossed into classical Greece and Rome, Greek physician Hippocrates of Kos, of “Hippocratic Oath” fame in the fourth century bce, drew on sources from Egypt and India to document the effects of lathering patients and research subjects in oils and essences from more than 300 different plants. Hippocrates and his contemporaries believed the pungent smell of the oils had effects beyond powerful perfumery. Theophrastus, born a year before Hippocrates passed away, in 371 bce, became the successor of Aristotle, and he wrote that “It is to be expected the perfumes should have medicinal properties in view of the virtues of their spices.”

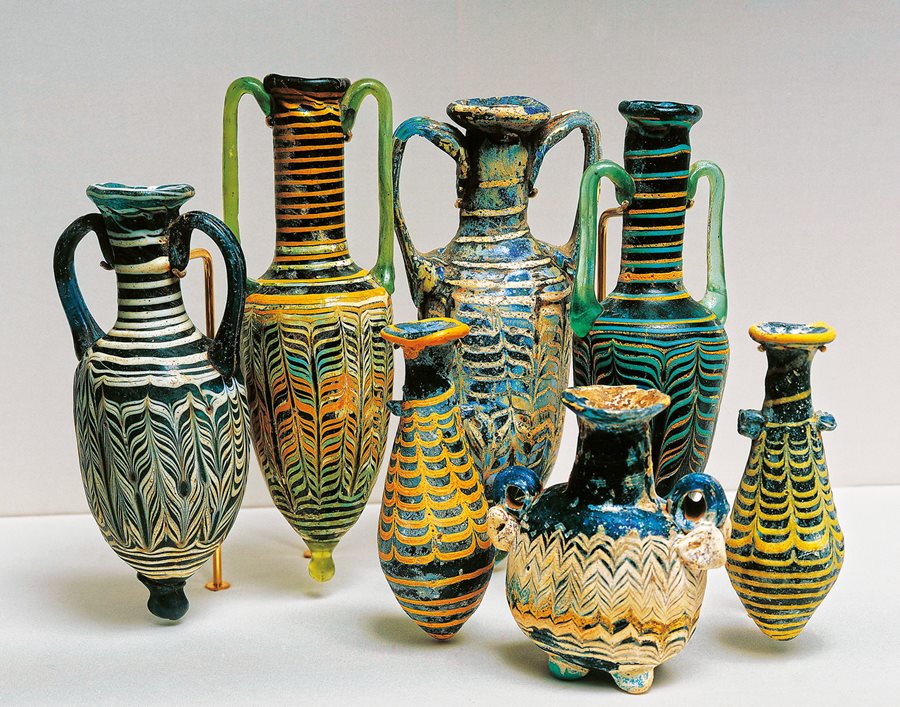

Later, other Greeks produced materials on plant oils and essences, including Dioscorides who, in 70 ce, wrote De Materia Medica, whose insights informed Romans, including Galen in the second century ce, as well as later Byzantine and Arab physicians. The Romans built upon Greek aromatic practices and expanded their application of the uses of oils, bathing in them, perfuming their beds and bodies and using them in massage. One of the Roman favorites was frankincense, and the trade from the southern Arabian Peninsula was so great the path from there to the Mediterranean ports became “the Frankincense Road.”

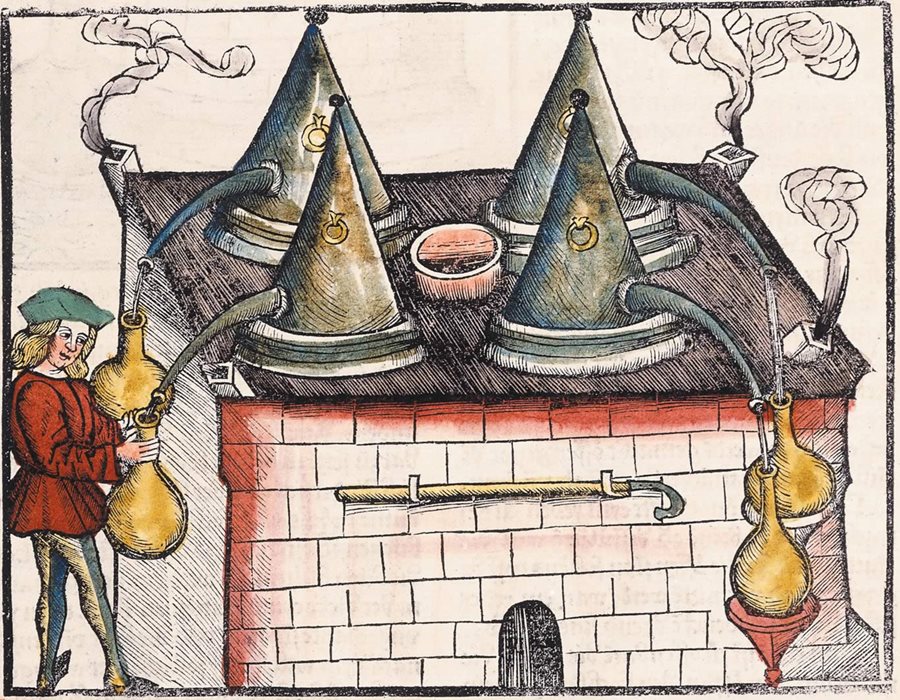

Following the fall of the Roman Empire in 476 ce, the oils continued to be distilled and widely used from Constantinople (now Istanbul) to Damascus, Cairo, Baghdad and across North Africa to Córdoba. Preeminent among the scholars of the scientific flourishing of the 10th century was Abu-‘Ali al-Husayn ibn-‘Abdallah ibn Sina, who was called Avicenna in the West. Born near Bukhara, in modern-day Uzbekistan, Ibn Sina was a polymath—philosopher, poet, physician and more—with a wide grasp of his Greek, Indian and Persian predecessors. Part of his oeuvre included detailed commentary on the therapeutic applications of more than 800 plants, and he is often credited with the discovery of the distillation process by which essential oils are extracted still today.

In the early 13th century, Ibn al-Baytar of Damascus, author of Kitab al-jami‘ li-mufradat al-adwiyah wa-al-aghdhiyah (Compendium on simple medicaments and food) expanded to various applications for 1,400 plants and oils, with a particular focus on the popular orange and rose waters of his day.

It was from these scholars that much knowledge of plant-based medicines, essences and oils emanated to Europe, where often it was monks who tended to the sick with herbal extractions. Oils were burned in attempts to ward off pestilence, such as when frankincense and pine were burned in the streets against bubonic plague, whose first wave appeared in 542 ce and killed more than 25 million people. In the later Middle Ages, perfumes and oils were carried back to Europe by returning soldiers of the Crusades, and later, Renaissance European herbalists, alchemists and spiritual leaders, such as Hildegard von Bingen, Nicholas Culpepper, Hieronymus Braunschweig and Paracelsus, all borrowed from the knowledge of Islamic forbears to begin dabbling in distilling oils such as lavender, rosemary, nutmeg and clove.

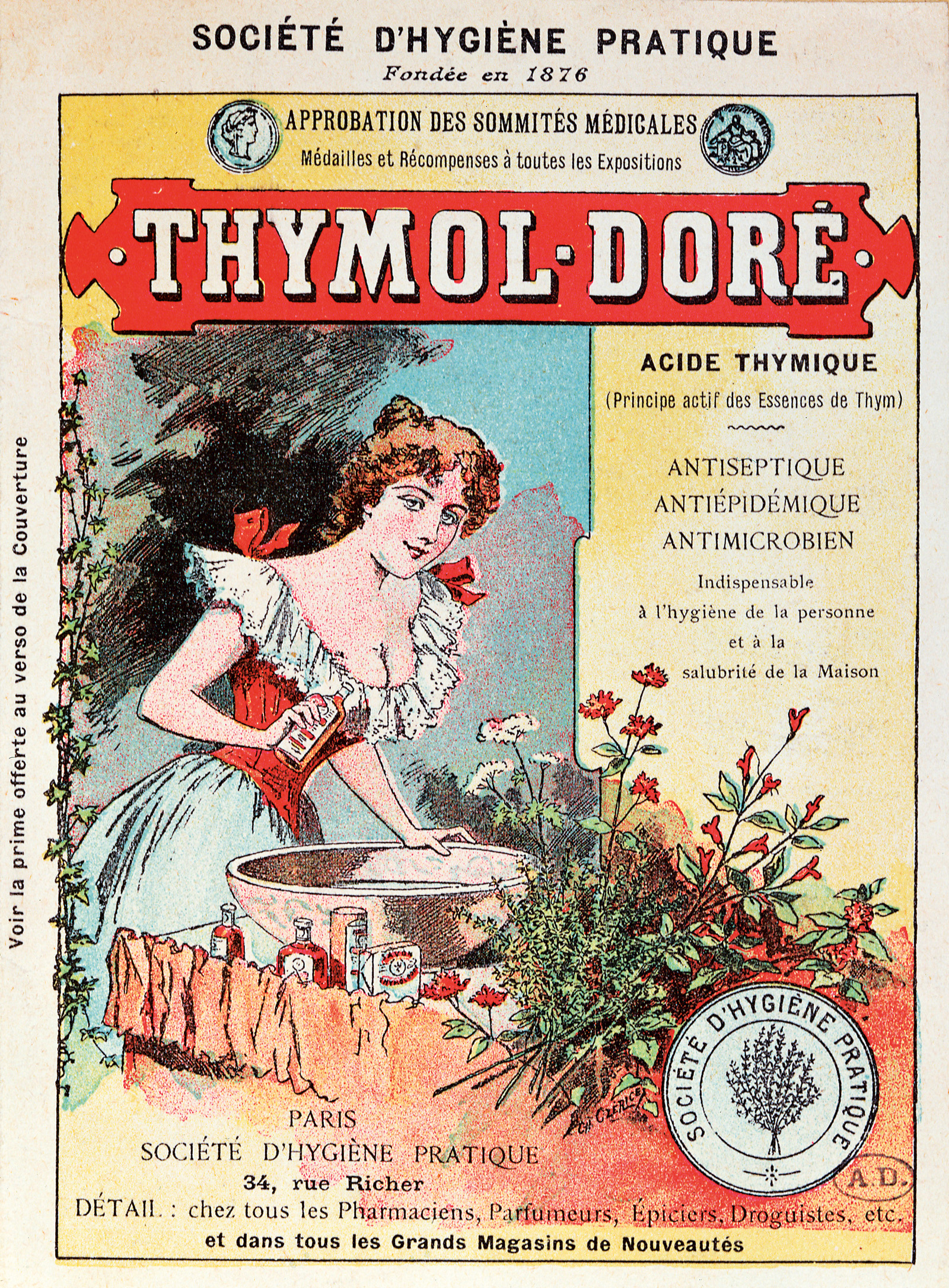

This set the stage for the Western fascination with using essential oils for aromatherapy in the early 20th century, widely credited to René-Maurice Gattefossé of France. Alongside his brothers, Gattefossé inherited an essential-oil business from his father in 1907, where they produced oils for the popular French perfume and medicinal industries. It was during the First World War that Gattefossé developed his method of using essential oils to aid injured soldiers, and modern aromatherapy was born.

Of the more than 90 types of essential oils on the market worldwide, frankincense remains among the top five, and among them it is the most historically referenced. Sourced from Boswellia sacra trees not only in the southern Arabian Peninsula, frankincense can also be found in the Horn of Africa. Its sap is still tapped, collected and sold on to global markets. Valued for its fragrance, taste and remedial effects, frankincense once was worth more per pound than gold throughout the Middle East, and it was sold as far as India, other areas in Asia and throughout Europe. Rather than being sold as resin, it is now most often distributed in the form of essential oil.

“The trade in frankincense has been going on since before the time of [the Great Pyramids], and people from outside Oman have long prized it,” says Ashad Chaudry, co-owner of Salalah Frankincense Oil, llc, which is one of doTERRA’s suppliers. Chaudry has been in the business for more than 40 years.

In Oman itself, says Chaudry, frankincense remains most popular in its resin form, which is burned for insect repellant and relaxation. It is also used as a base for oudh, pure perfumes, or blended in attar (aromatic sprays). Chaudry’s wholesale customers in the us and Europe “use them for a variety of purposes,” he says, including blending, reselling, cooking, cosmetics, perfumes and more.

“The uses of essential oils are endless,” says Chaudry, and despite mixed reviews from science, the mythos of essential oils only continues to move around the world and deepen its appeal. On blogs and social media, in pamphlets and advertisements from companies, the historical uses of these oils—factual and semilegendary—are being told and retold. Yet the science on essential oils remains mixed at best. A few have shown some antifungal or antibacterial properties, but evidence that essential oils can do all that some claim is anecdotal and lacks in clinical evidence.

But science does not deny that of our senses, the most powerfully memorable is that of scent. In that may be a clue to the enduring perception, the personal and often very individual experience that there’s much more to essential oils than what they do for one’s ailments.

Bollinger says she often shares the history of oils with her clients as they peruse the oil selections or oil combinations. She notes her own enthusiasm for the oils grew when she began noticing that “there are hundreds of essential oil references [in early religious writings], and we don’t even realize it.”

Brubaker had a similar experience.

“They’re not just old accounts of random plants,” she says, but “plants with specific purposes in mind for our well-being.”

Companies see this too. DoTERRA spokesperson Timothy Valentiner says it is “extremely important” to provide historical education to both salespeople and consumers. This education, he says, includes both “historical uses and benefits” as well as “scientific research and evidence.”

That potent promise—venerable wisdom and research-based results—explicitly advocated by leading essential oils companies, makes oils a kind of “soft science” for anyone today looking for natural paths to wellness.

It might come pure in an iridescent, apothecary-sized, hand-labeled bottle in a boutique, or it might come mixed as an ingredient in a family-sized bottle of what-have-you in a hypermarket. Either way, they come from one of the world’s oldest traditions for good living, one that still thrives where it began, and that still moves not only west, but to the world.