Art of Islamic Patterns: A Southeast Asian Rosette

- Arts

5

Written by Adam Williamson

In this final study of Islamic patterns from around the world, we travel to Southeast Asia to draw a radial pattern and experience the long tradition of architectural floral patterns carved in wood.

From Thailand to Malaysia and Indonesia, there is less focus on geometric, star rosettes like those found elsewhere in the Islamic world. Instead, designs here are generally cursive and vegetive. Many traditional houses feature window grills, brackets, architraves, doors and paneling intricately carved with floral biomorphic patterns, each one a formal, cohesive representation of forms and movements found in the surrounding jungle. The patterns have both practical and spiritual significance. Many utilitarian objects, too, from spoons to quail traps, are decorated and honored with these reverent designs.

Central to the designs is the spiral, from which the motifs and leaves sprout. This representation of continual growth and movement is called awan larat (moving cloud). The spiral or batang (stem) progresses from the benih (seed) or punca (source) like a plant growing toward the light.

This creates a centrifugal movement that reflects the progression of creation from the creator to infinity, sprouting daun (leaves) and bunga (flowers). Artisans stress that these motifs should coil back as if bowing in humility to the source or creator.

The development of motifs in this regional style is due to a convergence of influences. It is common that at the center of a composition sits the bunga teratai, or lotus, a form rooted in Hindu-Buddhist traditions. It is a representation of purity, rising through swampy waters and remaining pristine to surface and reveal its splendor.

Some leaves that sprout from the vines are reminiscent of Greco-Roman acanthus in the classic lobed and folded form. Other motifs originate locally, such as the daun lancasuka motif from Patani in south Thailand that is recognizable by characteristics like uptilted ends of the tendrils or ulir (volute). The kelopak dewa (deity leaf) can by sourced back to the sixth century as a motif that symbolizes earth’s natural, elemental energy.

Central to the Malay artisanal practice is the concept of semangat, which represents vital force or primal energy that is invested in things that are created. It is most relatable in the grain of wood and the growth movement of plants, yet it is a quality found everywhere. To align with Semangat before working, an artisan should ensure the workplace is clean and personal quarrels are settled. Then through meditation and prayer the artisan can be free of nafsu (personal needs). This will allow connection to the Guru Asal (Primordial Teacher), which will in turn enable the manifestation of the archetypal forms that have been passed down through the generations.

This excerpt from a Malay poem describes the approach to a composition:

Tumbuh berpunca,

Punca penuh rahsia,

Tumbuh tidak manenjak kawan,

Memanjat tidak memaut lawan,

Tetapi melingkar penuh mesra.

Growing from a source,

A source full of secrets,

Growing without piercing a friend,

Climbing without clinging to a rival,

But intertwining with grace and friendliness.

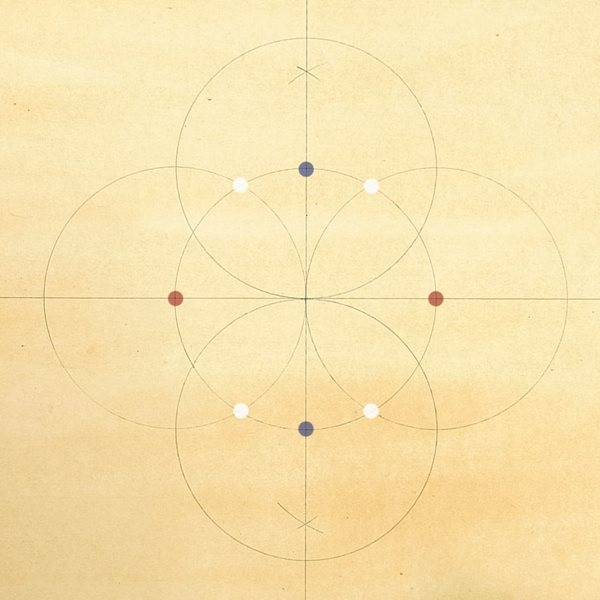

1.

• Across the midpoints of the page, draw a horizontal line. Measure its midpoint and, using the compass, inscribe a circle to fill the page.

• Retaining the same radius, place the compass where the circle intersects the horizontal line on the right (red). Draw a semicircle. Do the same on the left side.

• Place the compass on each of the four points where the semicircles meet the circle. Use the intersecting points of the top and bottom arcs (white) to find the points that define the vertical axis. Note these will be above and below your paper, so make sure you allow for space. Draw the vertical axis across the circle.

• From the top and bottom intersections of the circle with the vertical axis, draw semicircles (blue).

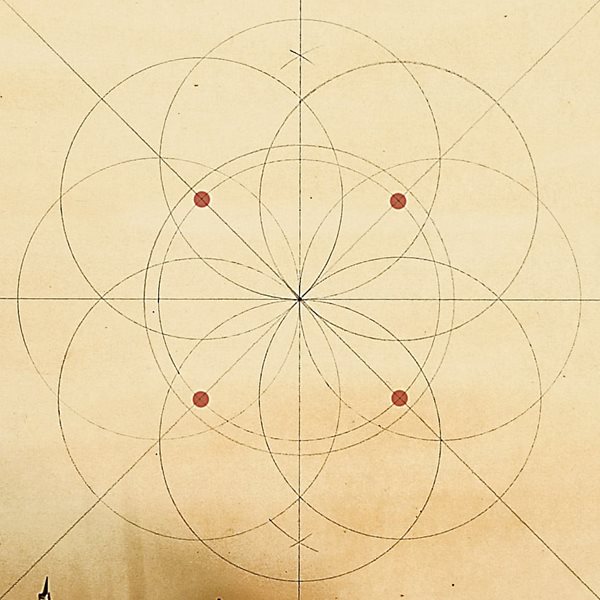

2.

• Draw the radial lines by aligning the straightedge with the tips of the petals (red), and cross the center point.

• Using these same intersections (red), draw four more circles using the same initial radius measurement.

• Place the circle in the center of the design increase the compass radius a little, and draw an additional circle, which will create a border.

3.

• Adjust the compass radius to match the length of one of the petals (white), and use this measurement to mark the distance from the central border and the outer border.

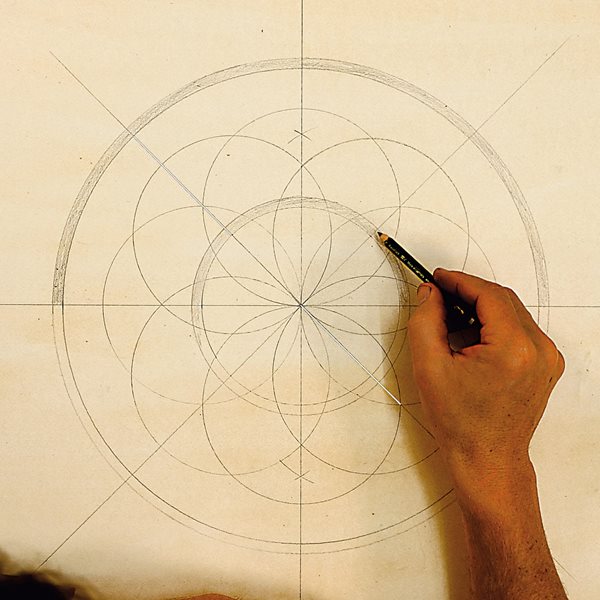

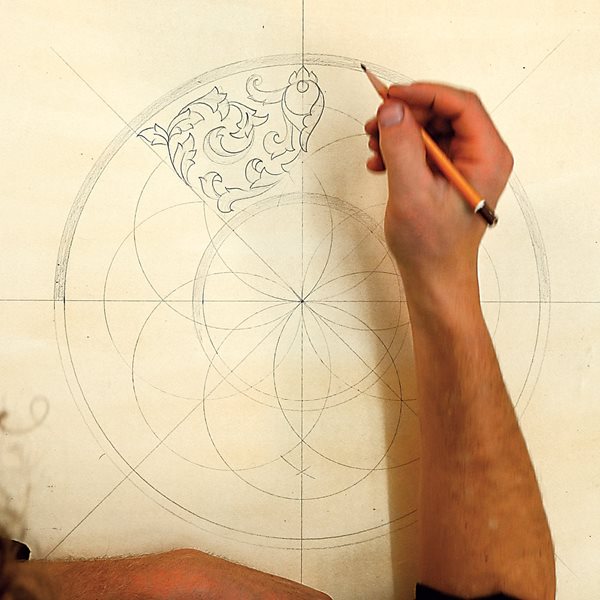

4.

• Between the two shaded border circles, inside 1/8 segment, draw the central folded motif, using a circle to help proportion the form.

• Draw a spiral that emanates from this motif.

• Add the leaves, lightly sketch in vesica forms to represent the leaf shapes before adding their lobes and details, making sure everything is positioned evenly.

5.

• At the center of the composition, use a compass to draw a circle and then the existing radial divisions to add the petals of the lotus.

6.

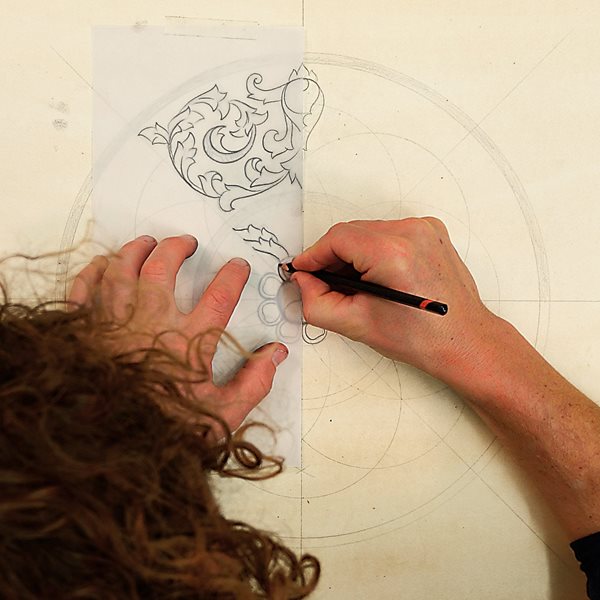

• Add half the flame petal to the central lotus motif.

• Fold a piece of tracing paper, align the fold with vertical line.

• Trace all the biomorphic elements with a 2B or 3B pencil.

7.

• Flip the folder tracing paper horizontally, pivoting on the vertical line.

• Retrace the biomorphic elements for a second time.

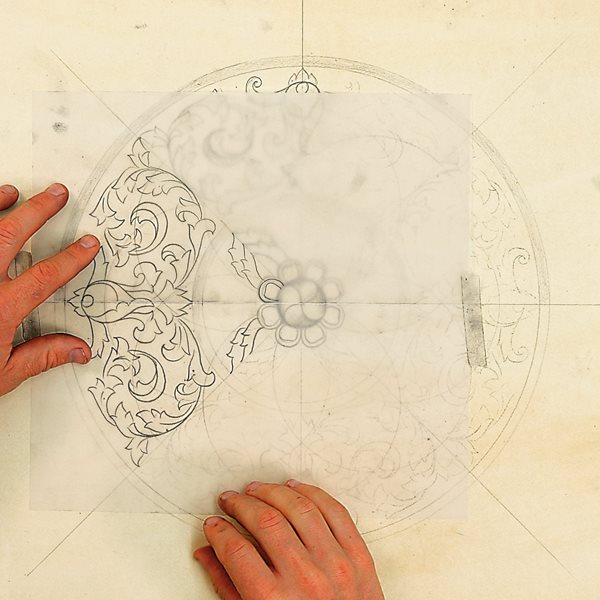

8.

• Open and flip the tracing paper so that the pencil lines are facing down.

• Align the traced unit with the empty quadrants of the rosette.

• When the tracing is in position using a polished stone or your finger nail, rub the back of the tracing paper to transfer the graphite from the tracing paper back into your design.

9.

• Rotate the tracing, and repeat the transfer process in each of the quadrants.

10.

• With a sharp 2B or 3B pencil, redraw the pattern.

• Use more pressure on the tips of the leaves and motifs, graduating your strokes.

11.

• Paint in a watery wash of walnut ink.

• Add highlights using a white conte pencil.

You may also be interested in...

A Fasting Journey Through Ramadan

Arts

What’s it like as a non-Muslim to fast during Ramadan? Writer Scott Baldauf shares his journey through the holy month where he uncovers resilience, empathy and the powerful unity found in shared traditions.

At Home in the World: A Conversation with Maryam Hassan

Arts

Growing up in London, at age 13, Maryam Hassan decided she’d move to Chicago one day. The city had glittered in her imagination because she was certain that it bore no resemblance to her hometown.

Polish Explorer's Manuscript on Arabia Helps Preserve Cultural Heritage

Arts

Nearly 200 years after his death, Polish adventurer and poet Waclaw Rzewuski’s manuscript documenting his experience in the Middle East has become important to advancing understanding of 19th-century Bedouin life and customs.