Going Pirogue, the Boats Feeding a Nation

- Arts

- Culture

10

Written by Tristan Rutherford

Photographed by Samantha Reinders

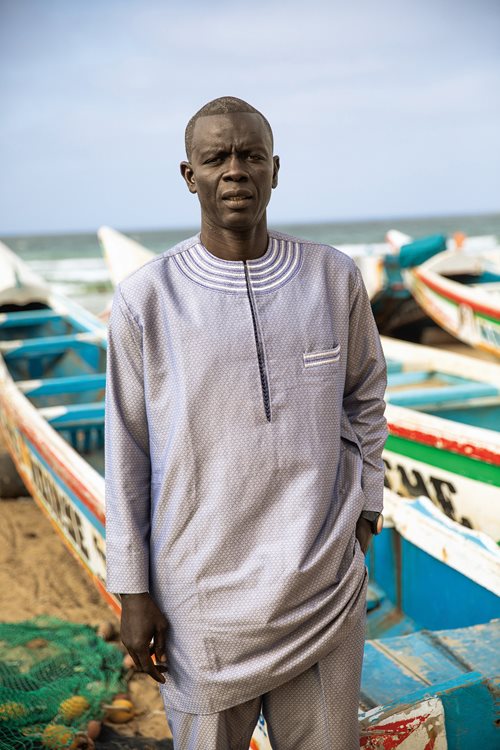

On the white sands of the Ouakam beaches, just beyond Senegal’s famed white-and-red Mosque of Divinity and its two towering minarets, rows of narrow, canoe-like pirogues line up. The boats are present every morning on the beach and begin to come alive in the early morning hours of daybreak. Senegalese fishermen from across the Dakar region, as they have done for hundreds of years, ready their multicolored pirogues for launch into the Atlantic, where they will spend hours or days at a time, catching giant trevally and marlin as they traverse the West African shoreline.

For more than a decade, pirogue designer Mor Diouf has crafted a range of pirogues in the chantier, or construction site, of Soumbédioune’s horseshoe bay. The chantier is the main boatyard in the region and known for its pirogue-building. Loose and half-constructed wood is strewn across the yard as dozens of boatbuilders work on various boat projects. They take only short breaks between hammering and sanding to rest under nearby mango trees or pause for a quick tea or coffee.

Diouf is currently building a new, 6-meter pirogue with a 6-person capacity, which is considered a small to midsized vessel. When complete in about four days, the pirogue will sell for CAF 900,000, or US $1,500. Fishing is serious business in Senegal, Diouf says amid the banging, whirring and electric sanding across the boatyard. So serious is it that even the country’s name reflects fishing and boating culture: It comes from Sunu gaal, which in the national Wolof language means “our pirogue.” (French is Senegal’s other national language, along with several regional languages.)

Along Senegal’s 530 kilometers of coast, small-scale fishing, also known as artisanal fishing, provides up to 75 percent of the consumed animal protein for its 17 million residents. Many local dishes feature fish, such as thieboudienne, a favorite fish recipe served with rice, peppers and sweet potatoes. Senegal’s national fish, the white grouper, or thiof, also appears in many dishes throughout the region. Just over a half a million fishermen, mongers and shipwrights comprise Senegal’s fishing industry and provide meat for its citizens.

Once a pirogue is complete and sold, Diouf says, the boats are immediately launched in the water. There is no ceremony or celebration of the pirogue’s completion, only the expectation the vessel will produce ample catch and return to shore with enough catch to feed the famlies of the fishermen, and sell the remaining supply at local markets.

Sometimes this business “has benefits, and sometimes people don’t buy” the boats, says Diouf, describing the pirogue-building industry in Senegal. How quickly a pirogue sells depends on its size, how much weight it can withstand, how long it takes to build and how many fishermen can use it at one time.

Some 20,000 pirogues have been crafted at the chantier, just a 20-minute drive south from Ouakam, and while many new boats are always under construction, many older boats remain at the boatyard for repair, while others are being retired and prepared for disassembly.

Senegal, or Sunu gaal, in the national Wolof language, means “our pirogue.”

Diouf began his career as a net fisherman using a paddle-powered pirogue made for a single person. He soon transitioned to boatbuilding, however, and today his pirogues are known for being faster and sturdier than others in the region. The recent completion of one of his 20-meter pirogues, designed to be at sea for a week at a time, took 15 days to build and a crew of 10 men to heave it into the water.

It took “two days work, two days rest,” to complete the large boat, says Diouf, who earned about $10,000 from the sale. With so much energy and time poured into each pirogue build, the boatbuilders depend on the shade of the nearby trees and the brewing stations stocked with hot water, tea and Nescafe instant coffee for short breaks.

Diouf says the larger pirogues are built to sustain a mounted outboard engine—or two—and for long trips store provisions such as coconuts, groundnuts, oranges and rice for when the fishermen may stay out at sea for a week or more at a time. While the fishermen are at sea, however, there is not much entertainment, Diouf says. There is no singing, storytelling or listening to music on one’s smartphone, for example. It’s all business.

It’s “just catching fish,” says Diouf, shifting between hammering nails and fitting protective rubber seals between the joins of samba wood and redwood.

Piles of the samba wood at the boatyard arrive frequently via shipping containers from Cote d’Ivoire, also located on the West African coastline, with five countries between it and Senegal. The yellow wood is light and flexible, famous for its use in crafting pirogues. Pirogue hulls, however, are made from the more durable West African redwood from Casamance, Senegal’s tropical southern region. Redwood can withstand saltwater conditions for about a decade before needing to be replaced.

Earlier this year, as a well-meaning gesture from foreign fishing enterprises who fish in Senegalese waters, 38 fiberglass fishing canoes were gifted to Senegal by a French multinational company and Japan’s International Cooperation Agency. These reinforced plastic canoes require no tree felling and offer cold-storage boxes built in the hull. While these fiberglass boats are thought to be unsinkable and longer-lasting, perhaps, they’re not made in the local boat-building tradition, nor do they feature the colorful, whimsical artwork hand-painted across the sides of the wooden pirogues.

“We wouldn’t get on a fiberglass boat,” Diouf says emphatically, almost offended by the thought. “Don’t even talk to me about it.”

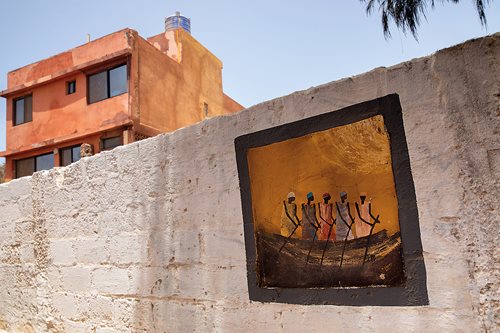

Each boat built at the chantier is painted with blue waves and gold swirls, with rising red suns and green stars to echo the Senegalese flag. Boat names honor loved ones, such as “Mama Samba Diop,” “Mansour Sy” and “Abdou Aziz.” Smaller motifs at the bow add extra élan: a US flag, or the insignia of the popular soccer club in Barcelona, or a nod to international soccer icon Cristiano Ronaldo. The current pirogue art trend is for more color than ever, but as the boats are fishing far from shore, rarely seen after launch, it begs the question: Why bother painting them at all?

“People want to decorate them because everybody wants their own unique design,” says specialist pirogue painter Demba Gaye, explaining the regional uniqueness of the motifs. “If a boat comes from Yoff,” an important Dakar fishing suburb, “the designs will show it. If a boat is from Ngor, you can also tell.”

Retired fisher and pirogue owner Ousmane has witnessed Dakar’s fishing industry expand through the years, and he has intimately known the importance of seeing the pirogue boats supply fish for a nation.

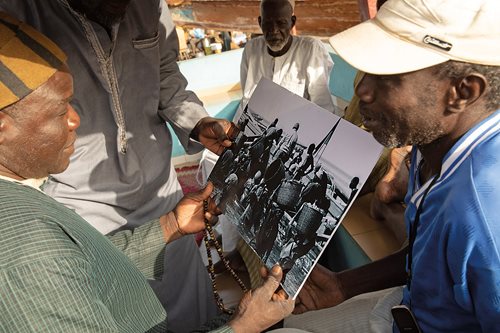

“Our grandfathers and fathers were all fishers,” says Ousmane, a well-known and respected senior among the local pirogue fishing community. “After we finished school and ate with our family, our grandfathers would talk about fishing and how it works.”

Beyond the fishing culture and its necessity for feeding a nation, fishing as an activity is also used as a method to teach children and young adults life lessons, Ousmane says. If a male student is failing at school, for example, someone takes him fishing.

“It’s better for our people to fish than doing a bad thing on land,” he says.

It’s also good exercise for the mind and body to catch large fish, he says, mentioning the largest fish he ever caught was a fighting marlin, which can weigh upwards of 226 kilograms. But one does not simply know how to catch large fish. It is a learned skill, Ousmane says.

“You have to be taught the technique to catch one,” he says.

Yet big fish like fighting marlins are becoming harder to fish from the sea. There is an overcrowding beginning to occur on the shoreline, with foreign boats and fishermen encroaching on Senegalese waters. They’re taking more fish than can be replenished during a natural cycle.

“At night they come,” says Ousmane’s friend Assane, also a longtime fisherman. “If people just took a small amount, giving fish time to reproduce, it would be OK. But with big boats from China or Russia, they take all of them.”

Many of the local Senegalese fishermen are starting to go out and come home on their pirogues empty-handed, Assane says, and not only are fish quantities decreasing along the coastline, but now Senegalese divers are coming in at night and spearfishing the larger fish while the pirogue fishermen are sleeping and off duty.

“They dive with a (waterproof) torch so strong that it’s like daylight underwater,” Ousmane says.

Some of the older retirees are noticing the possibility that making a living on pirogues in the future may eventually become an unreliable option.

“A lot of people are going to America, or Spain, or France because they don’t have income,” says Assane, who wonders if the pirogue culture will eventually sail away too.

In the suburb of Ngor, between Oukam and Yoff, pirogues are now being used in different ways to help sustain the profession. For a $2 ride, which includes a life jacket, the boats act as tourist shuttles as they weave through the waves to Ngor Island across the bay. To ride in a pirogue is to understand why they are perfectly suited to West African waters. Their U-shaped hulls push the sea aside, allowing the boat to glide through rough waters. A raised stern tosses away spray and the pirogues’ lengthways, banana-like curve aids maneuverability. Pirogues are agile like dolphins rather than large and difficult to steer, like a whale. In other areas of Senegal, pirogues have adapted to become riverine passenger and fishing crafts, as well, made with flatter hulls and smaller sails. They also continue to evolve in size to be able to accept larger cargo.

But the pirogue community has not given up on its tradition, or future, and many in the boating community, whether fisherman or boatbuilder, are dialoguing about possible solutions to preserve pirogue fishing in Ouakam.

“The pirogue is a family friend for generations, part of a community which is very social.”

—Gaoussou Gueye

The African Confederation of Artisanal Fisheries Professional Organization president, Gaoussou Gueye, who presides over the African organization of artisanal fishers, a confederation of small-scale fisheries from 26 African states, concedes that overfishing by large, foreign fishing enterprises is “evidently a problem.” It is one they hope to resolve in the future since 80 percent of the catch in Senegal comes from artisanal fishers and landlocked West African countries, such as Mali and Burkina Faso, also rely on the fish from Senegal ports.

“Coastal communities and civil societies are asking for transparency as to which legal and illegal boats are fishing in Senegalese waters,” he says. “We propose taking initiatives to measure stocks and their durability to better regulate food security and social stability.”

Some fishermen believe it is a good idea to reserve small pelagic fish solely for artisanal fishing methods and help replenish the available fish faster. Tradition is also at stake, the president says.

“Sometimes the pirogue is like a baby. … The boat nourishes and entertains the family. That toddler will inherit the culture before doing the same work as his parents,” he says. “The pirogue is a family friend for generations, part of a community which is very social.”

Gueye says the community is so social, in fact, if fishermen come back with no fish, they are entitled to take two or three fish from another fisherman to prepare a meal and have something to eat.

It seems many are determined to keep the pirogues, and all they represent to Senegal, in tact for generations to come. With millions depending on these pirogues to come back with fish to eat and sell each day, more must be done to preserve the fish supply and maintain the tradition of pirogue fishing.

“The base of our food is fish,” says Gueye. “This is why pirogues are extremely important in the lives of Senegalese.”

About the Author

Samantha Reinders

Samantha Reinders (samreinders.com; @samreinders) is an award-winning photographer, book editor, multimedia producer and workshop leader based in Cape Town, South Africa. She holds a master’s degree in visual communication from Ohio University, and her work has been published in Time, Vogue, The New York Times and more.

Tristan Rutherford

Tristan Rutherford is a 7-time award-winning journalist. His writing appears in The Sunday Times and the Atlantic.

You may also be interested in...

The Heart-Moving Sound of Zanzibar

Arts

Like Zanzibar itself, the ensemble style of music known as taarab brings together a blend of African, Arabic, Indian and European elements. Yet it stands on its own as a distinctive art form—for over a century, it has served as the island’s signature sound.

Revival Looms

Arts

In Georgia Borchalo rugs are making a tentative comeback amid growing recognition of the uniqueness of ethnic Azerbaijani weaving. There’s hope that this tradition can be saved.

The Resilience of Craft - Three Exhibitions at Venice Biennale Uphold Legacy of Traditional Arts

Arts

The Venice Biennale sheds light on lesser-known narratives outside of the international art world.