America's Music of the Nile

- Arts

- Music

11

Written by Jonathan Friedlander

Art courtesy of Jonathan Friedlander

Of the world’s great rivers, there are perhaps none as iconic, even celebrated, as the Nile.

This 6,650-kilometer natural wonder has acquired universal recognition particularly through its association with the pyramids, temples and tombs Egyptians built along and near its banks. Beginning in the mid-19th century, as “Egyptomania” swept popular culture in both Europe and the United States, no country outside of Egypt itself has paid so much attention to the river Nile—glorifying it, mythologizing it, exoticizing it—as the US. And nowhere was this more apparent than in popular music, where nearly 100 musical compositions, produced over some 125 years, have used the Nile as a motif, a metaphor or both. These compositions fall into nearly every category of music of their times, but the most notable uses of the Nile arose during the jazz period, peaking in the second half of the 20th century and continues to this day.

Egyptomania—as it was called at the time—was a form of Orientalism that was both sincere fascination and colonialist exploitation. Stimulated by the advent of the steamship and epitomized by French Emperor Napoleon’s 1799 invasion of Egypt, whose forces included not only soldiers but also scholars, the popularization of all things Egyptian—both real and imagined—fed the rising consumerism of the new Industrial Age. Vivid, often lurid images of the far-away and the ancient, appeared on Egypt-themed trading cards, coffee cans, beef jars, chocolates, cosmetics, Camel cigarettes and much more.

Hey, come along with me …

Take my hand and see …

Creations planned along the old black Nile

My ancestry, history is calling me.

—Gregory Porter, 2009

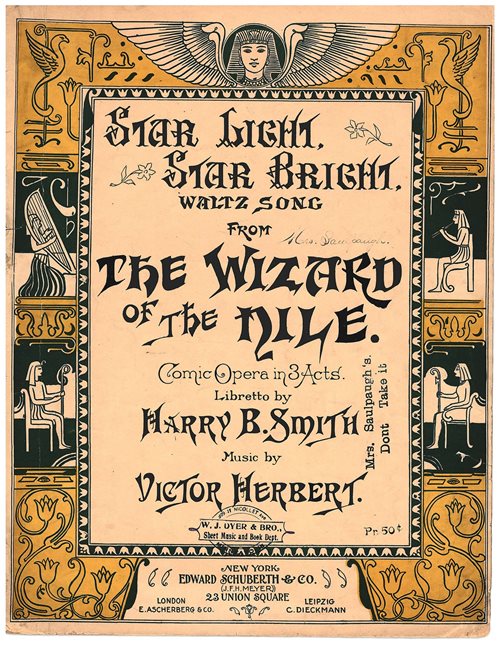

No less was true in music, from Broadway to neighborhood music stores. In 1885 the highly successful run of The Wizard of the Nile, scored for Broadway by Victor Herbert, was so successful it jumpstarted the composer’s career, who went on to become one of America’s most prolific artists of musical theater. The three-act comic operetta opened with the refrain, “Father Nile, keep us in thy care,” sung by actors portraying boatmen and water carriers whose pleas came from a hymn written more than 40 centuries ago in the hieroglyphs of Middle Egypt.

Left Song sheet titled “Star Light Star Bright, Waltz Song From The Wizard of the Nile, Comic Opera in 3 Acts,” by Harry B. Smith and Victor Herbert. At that time there were no records. Right “The Nile Bride, Egypt.” Trading Card from the Holidays series that were issued in 1890.

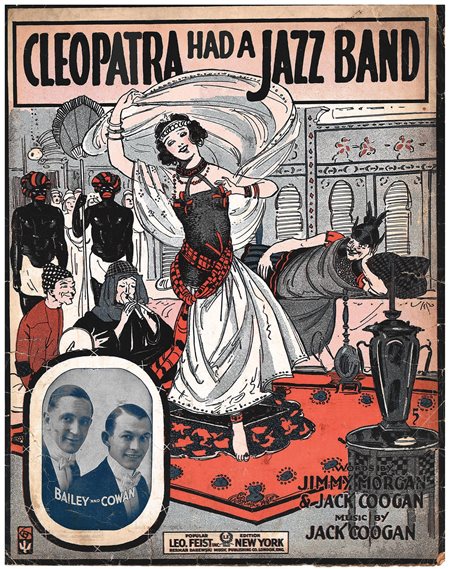

On the shelves of music stores, some 50 novelty love songs appeared using the Nile in titles and lyrics, published in colorful sheet-music form and later also sold as 10-inch, 78-rpm, shellac records for Victrola record players for homes, night clubs and dance halls. Variety shows, revues and cabarets used the songs too, including the lavish Ziegfeld Follies of 1916 that featured among its sketches a song by the eminent composer Jerome Kern titled “My Lady of the Nile.” The following year “Cleopatra Had a Jazz Band” (“in her castle on the Nile / ev’ry night she gave a jazz dance in her queer Egyptian style”) hit music stores nationwide and sold thousands. Thus did the Nile flow into the American musical scene.

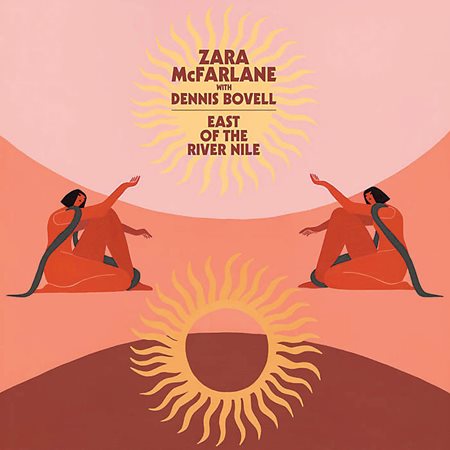

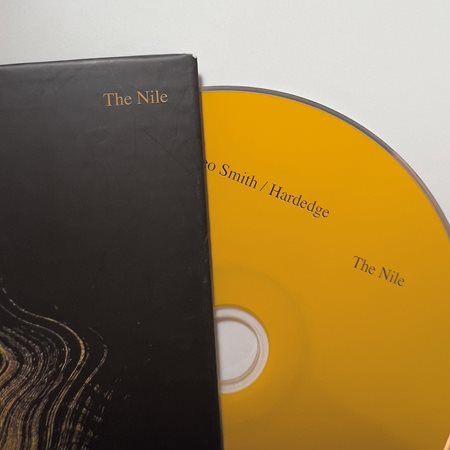

Left The influence of the Nile extended to British-born jazz singer Zara McFarlane’s 2019 single “East of the River Nile.” Center In 2014, Indie label Hardedge released a four-composition LP from American jazz trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith, who released his first album more than 40 years before in 1972. Right Released in 1966 by jazz multi-instrumentalist Yusef Lateef for Impulse! Records, A Flat, G Flat and C, which includes the track, “Nile Valley Blues,” helped the Tennessee-born artist pioneer the world-music scene.

These sounds fell on ears further primed for the novelty of exotica by the rising numbers of travelogs, newspaper accounts, and some of the first of what now might be called immersive experiences: The 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago prominently featured the enticements of Cairo Street, which drew large audiences and went on to be replicated by world’s fairs and expositions elsewhere, explains musicologist Anne Rasmussen of the College of William and Mary. These kinds of spectacles, she adds, were enlivened and bolstered by music, provided by a growing cadre of local musicians as well as immigrants and their descendants who “played Oriental”—as it was regarded at the time.

The 1930s saw the demise of the sheet music industry and record sales dwindled in the face of financial hardships of the Great Depression. By then Americans were able to hear music freely on the radio, especially tunes of the big band era. After World War II their popularity gave way to smaller groups such as the Duprees whose 1962 hit “You Belong to Me” invited listeners to imagine flying to “see the pyramids along the Nile” or “the marketplace in Old Algiers” and other tantalizingly exoticized lands. In the latter part of the century, Carlos Santana released his spiritual odyssey “The Nile” in 1982, and country singer Pam Tillis sang “Cleopatra, Queen of Denial” in 1992. All reflected and shaped a popular, and stereotype-laden, perception of the great river and Egypt. Likewise numerous musical scores accompanying Hollywood movies of the era did the same, such as Love Songs of the Nile from the 1933 cliché film The Barbarian.

Rasmussen identifies several stylistic components and conventions among these performances of yesteryear whose titles referenced the Nile. These include minor scales and bent notes “pregnant with the air of the Orient,” as well as ornamentation or embroidery of a melody that lent a touch of the exotic or made it sound “just slightly east of the Atlantic.”

“I think it’s very likely that many of these references are, if not nationalistically, then culturally, expressions of Kemet—Black ancient Egypt.”

—Michael Frishkopf

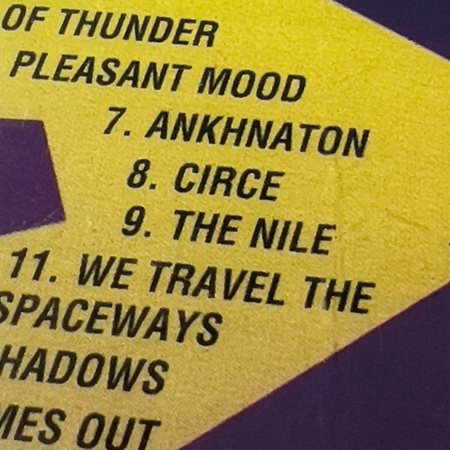

These sounds, she adds, also reached the ears of jazz players, led much by those African American musicians who in the 1950s were leading the rise of a revolutionary form of jazz called Bebop. This movement, says Richard Brent Turner, a scholar of African American religious history and music at the University of Iowa, created a fertile cultural and intellectual ground for the musician’s embrace of the Middle East in general and, for more than a few, Islam. This flourishing movement swept in others as well, creating a disparate, yet cohesive, community of instrumentalists who composed more than 30 jazz refrains evoking the Nile’s sunrises, sunsets, moonrises, upper and lower regions, the fertility of its delta, its populous banks, and even animal life along its shores. Their contributions facilitated the growth of contemporary/modern jazz forms and genres—cool, fusion, modal, free, avant garde, funk/soul, latin, astral, spiritual, and the straight-ahead jazz heard today. In 1957 Sun Ra, whose name draws on the Pharaonic sun god, wrote for his composition “Enticement”:

Imagination is a magic carpet

Upon which we may soar

To distant lands and climes…

I cordially entice you,

I diligently tempt you:

Step upon my magic carpet of sound,

And share my adventures

On the land of pleasure Hi Fi

Niles Blue, White, Black

From central Africa and the highlands of Ethiopia flow the White Nile and the larger Blue Nile, and they join in Khartoum, Sudan, to flow north as the single river Nile. In 1970 pianist and harpist Alice Coltrane, saxophonists Pharoah Sanders and Joe Henderson, bassist Ron Carter and drummer Ben Riley produced “Blue Nile,” which featured Coltrane at the helm of a musical journey propelled by her glistening harp runs and tranquil flutes underlaid by a deep and resonant bass line. Recorded on the Impulse label, it is regarded as a seminal work in the annals of spiritual jazz. In 2016 it was reinterpreted by the Atlantis Jazz Ensemble, whose up-tempo, hard-swinging version “is definitely meant to elevate the soul,” says the group’s cofounder and pianist Pierre Chretien. The Blue and White branches of the Nile also come together under African Skies, Kelan Phil Cohran’s 1993 cosmic masterpiece, considered one of his finest works, a slow build that combines East African tones and Western jazz fusions.

“I called it ‘Black Nile,’ not as a nationalistic device but to locate it,” pointed out saxophonist Wayne Shorter in a comment chronicled in jazz critic Nat Hentoff’s liner notes. “I was thinking of the Egyptian civilization which at the time of its greatest achievements was a black civilization. In the piece itself, I tried to get a feeling flowing—a depiction of the river route.” Released originally in 1964 on the Blue Note label, “Black Nile” has been re-issued more than 50 times and, in 2009, Gregory Porter set lyrics to it: “Hey come along with me / take my hand and see, Creations planned along the old black Nile, my ancestry, history is calling me.”

MaseQua Myers and Jami Ayinde take up the same theme in their soulful 1975 jazz refrain “Black Land of the Nile,” joined by saxophonist Chico Freeman. “I think it’s very likely that many of these references are, if not nationalistically, then culturally, expressions of Kemet—Black ancient Egypt,” remarks musicologist Michael Frishkopf of the University of Alberta in Canada. Moreover, it looms beyond boundaries and serves as an important connector between the continent’s coastal north and Sub-Saharan regions while also traversing the cultural spheres of Afrocentrism and Afrofuturism.

“The stately Middle Eastern theme moves like one of Cleopatra’s opulent barges.”

—Ira Gitler

Pianist McCoy Tyner embraced Islam in 1955 at the age of 17, and in 1970 led a groundbreaking collaboration among himself, Coltrane, Shorter, Carter, drummer Elvin Jones and sax player Gary Bartz on “Message from the Nile,” which epitomized the cutting edge of jazz and remains influential. The history that transpired on and along the Nile evoked by the music is an “integral part of the experiences of Black people,” noted McCoy. This sentiment was mirrored in pianist Randy Weston’s 2002 composition “Roots of the Nile,” inspired by his travels to Egypt.

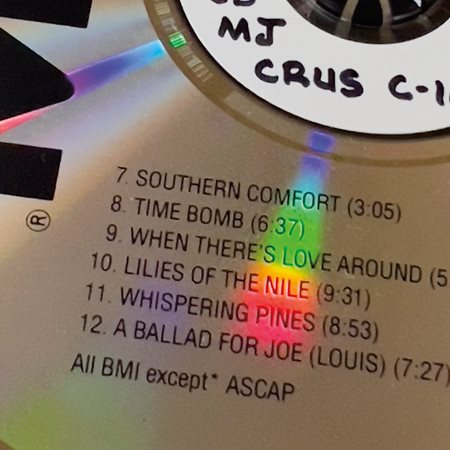

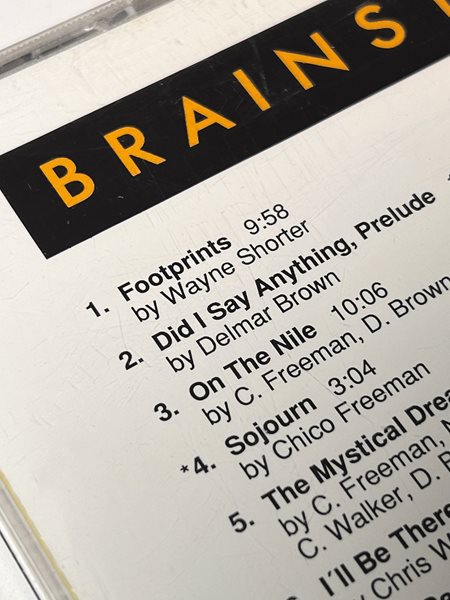

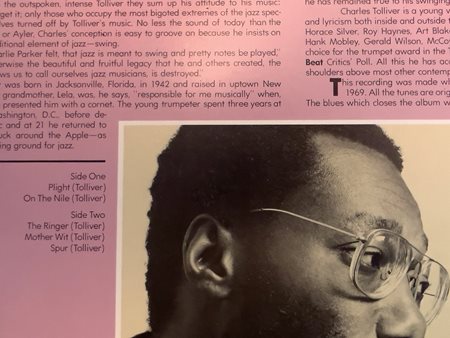

Where on the Nile?

“The stately Middle Eastern theme moves like one of Cleopatra’s opulent barges,” wrote jazz critic Ira Gitler in his liner notes to saxophonist Jackie McClean’s 1975 rendition of “On the Nile,” composed in 1969 by trumpeter Charles Tolliver and recorded by numerous artists, each a record of an encounter with a Nile that conjures a wide range of feelings and sensations dictated both by the real and the imaginary. “I like to rumble, I take the most difficult routes for improvisation ... no gimmicks, just hard-core jazz music,” Tolliver confided in a Downbeat magazine interview. Henceforth he and his fellow musicians, among them pianist Stanley Cowell, pursued a musical journey in a performance that rivals the best of any in their careers. Tolliver joined up in 2011 to revisit this number with Archie Shepp on sax in a lavish orchestral adaptation staged in Germany. Los Angeles-based pianist Horace Tapscott, founder of the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra, as well as Shari Cassity, who played in Tolliver’s Big Band, followed suit with their own adaptations of this masterwork; and saxophonist Chico Freeman’s 1990 recording is driven by a harmonious mix of Afro-Latin rhythms.

While saxophones reigned supreme at the outset of the modern jazz era, the playful and lyrical piano also affirmed its place in the repertoire, an instrument Danish pianist Maria Kannegaard used in 2008 in her gentle, hypnotic “Drifting Along the Nile,” which is set to a circularly repeated, three-chord pattern that references “minimalist classicism without sounding anything like it,” wrote John Kelman in his AllAboutJazz.com review. The place of the piano up front and center is also evident in the soulful arrangement accentuated by the striking cords of Ahmad Jamal, one of American’s most influential jazz pianists, bandleaders and educators as he charted a private space for the listener’s own river journey, “Somewhere Along the Nile” in 1974. The cruise is extended to the river’s upper dominions in a 1986 piece titled “6 A.M. / Walking on the Nile” by keyboard and synthesizer master Joe Zawinul, of Weather Report fame, which recalled the sights and sounds of daily lives “glimpsed or imagined.”

“I was in the Nile Valley just as a traveler, ... [I] felt a parallel between that valley and the richness of the blues form.”

—Yusef Lateef

The ruminations of two saxophonists, a trumpeter and flautist frame the Nile with references to its geographic regions, and its fertile flood plains and delta. “I was in the Nile Valley just as a traveler,” recalls Yusef Lateef, a leading reed instrumentalist of his era. “[I] felt a parallel between that valley and the richness of the blues form,” which he conveyed in 1966 in his “Nile Valley Blues,” a performance roused by breathy vocals, some spoken through the flute. Other vocals resonate in Carlos Garnett’s 1974 composition “Banks of the Nile,” as Dee Dee Bridgewater, accompanied by full-sounding horn lines, takes lead and saxophonist Garnett embarks on the soprano while “the horns also develop in gradually rising patterns,” wrote Michael Cuscuna in the LP’s liner notes. “Lower Nile” was a spirited 1977 composition by Arthur Blythe in which once again the saxophone stands supreme: Departing from his standard free jazz and avant-garde modes, Blythe settles into a Funk Jazz classic that features a steady percussive base line and melodic arabesque patterns that become even more riveting in the later 2009 rendition by cellist Erik Friedlander. Similarly the winding Middle Eastern sway that underscores Tom Harrell’s 2015 evocation “Delta of the Nile” showcases his talent as “a deft cool-tone trumpeter and extremely skilled composer” while Omer Avital played the ‘ud to give this standout number a touch of the sublime.

The Sun, Moon, River

A Nile Still Runs Through the US

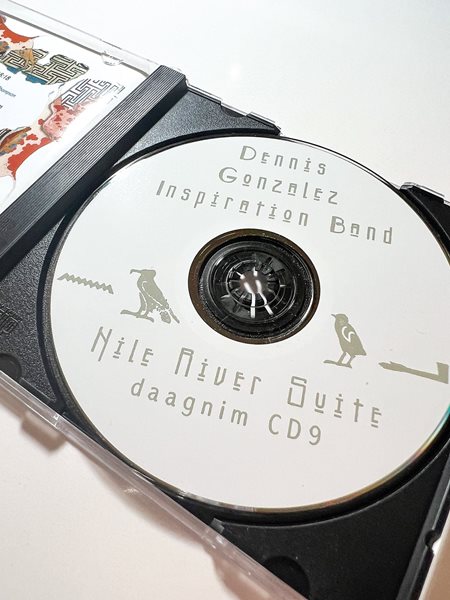

The growth and development of jazz continues, and with it, the appearance of Middle Eastern and Nile-related titles through genres, styles and conventions. Consider the vanguard trumpeter and musical theorist Wadada Leo Smith, who in 2014 teamed up with electro-sound designer Hardedge for a sizzling backdrop on “The Nile.” In 2003 Dennis González’s Inspiration Band released “The Nile River Suite,” a three-part study in tranquility and pop-up lyrical moments that segues into a heartfelt groove, one whose flow reminds musicians and audiences alike that a musical Nile continues to run through us all.

You may also be interested in...

Berlin’s Transcultural Jam

Arts

Culture

A musical wave has been swelling for a decade in the German capital, which one local analyst now calls “the city of choice for a new generation of cultural talent from the Middle East and North Africa”—part of the greater demographic shift that has made people of Arab backgrounds Berlin’s fourth-largest ethnic-identity group. In street jams, clubs, studios, concert halls and online, new mixes of musicians are blending notes and ideas into genre-bending, transcultural fusions. “What we as artists in Berlin can do is tear down the borders in our head and invite others to do the same,” says musician Jamila Al-Yousef.

Nass El Ghiwane, the Voice of Morocco

Arts

This group of five young folk musicians became the voice of Morocco in the 1960s and beyond. Martin Scorsese called them “the Rolling Stones of North Africa,” but to Moroccans they were the sound of an entire generation in a charged moment of global pop culture.

Record, Remix, Repeat

Arts

For more than 10 years, Moroccan native and New York resident Hatim Belyamani has focused his non-profit Remix⟷Culture on offering digital sample and remix tools that give exposure and preserve access for traditional acoustic music around the world.