Record, Remix, Repeat

- Arts

- Music

Written by Kay Hardy Campbell

Photographed by David H. Wells

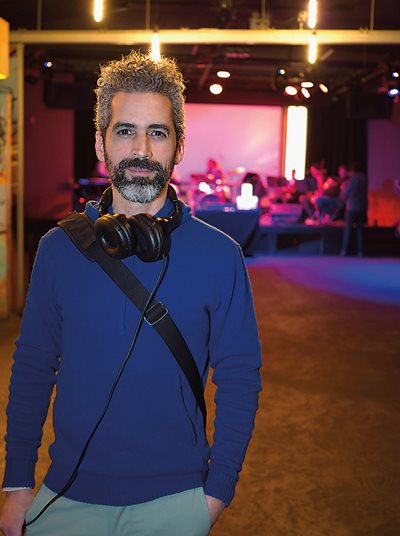

Hatim Belyamani is grinning as he and nine other musical artists take their places on the small stage to the applause of a sellout, standing-room-only audience of some 200 people at Public Records, a state-of-the-art music hall in Brooklyn. Shaking off nerves, Belyamani slides behind his digital mixing board, grips the mic and introduces his fellow performers for the musical journey they have prepared and called Tanfis, an Arabic word describing a spiritual release and renewal akin to releasing a long-held breath. All has been made possible by the nonprofit Remix⟷Culture, which he founded to record, film, digitally remix and disseminate the sounds of musicians playing within underrepresented acoustic traditions around the world.

“After three months of working together, we collectively designed what tonight’s experience is going to be,” he says.

He pauses, the slightest hesitation. If all goes well, this collaboration among acoustic musicians, DJs and remix artists drawing on music from Southwest Asia and North Africa will yield a compelling blend of live music, electronic dance and immersive videos that will envelope the room, triggering catharsis. Or this work, a culmination of sorts for Remix⟷Culture’s years spent collecting and remixing overlooked folk music for shows just like this one, could lead to himself and nine players alone by the end of the night. A deep breath, another smile. “This is really a co-creation of all 10 of us and we really hope you stay for the full three hours,” he tells the crowd.

As the music grows more energetic, Belyamani watches people’s reactions. Although this is a far cry from the traditional Gnawa music (described by some as Moroccan blues) that first inspired Belyamani’s work, if the audience connects with Tanfis (the show title is an Arabic word describing a spiritual process of release and renewal akin to releasing a long-held breath), the end-result will be the same as that experienced at a Gnawa lila, a night of communal prayer, healing and release through rhythmic chant, music and dance. In the audience, the music begins to take hold. People, rapt, begin to dance, bodies pulsing along as the beat grows more intense and slowing when the rhythm grows faint.

This show is a direct correlation to Remix⟷Culture’s ongoing mission to “explore the ties between acoustic and electronic music, between the ancient, the past and the future, between the deep ancestral wisdom and the future of all possibilities,” Belyamani says.

It has been more than 10 years since Belyamani started what would eventually become Remix⟷Culture, his New York-based nonprofit organization focused on creating awareness of under-represented musical genres and subgenres from around the world.

Now, as both founder and executive director of the organization, in many ways Belyamani is Remix⟷Culture.

It all goes back to his childhood in Casablanca, he explains, when he was growing up in a music-loving family. He was as likely to come home to his parents spinning the smooth tones of famed Egyptian singer Abdel Halim Hafez as he was to wake up to the orchestral fury of Rachmaninov, the pop harmonies of The Beatles or the swinging rhythms of Duke Ellington’s jazz. “My ear and my brain were exposed to all of that from an early age,” he says. “We also listened to Moroccan music, but it was a small, narrow spectrum,” he said in a 2019 interview with The Cedar.

His clan also gravitated toward performance. Belyamani’s father, a radiologist, regularly pulled out the ’ud at parties and family gatherings. Belyamani and his two brothers, who all started learning piano as children at Casablanca’s Conservatoire de Musique, became skilled enough to compete in classical piano playing contests. As a teenager Belyamani won prizes for his classical playing while also learning to play jazz and guitar—but he casually dismissed most Moroccan music. It took seeing a video of former Led Zeppelin lead singer Robert Plant in Marrakesh singing a Gnawa tune to get teenaged Belyamani to start thinking about his own culture’s music and how it fit in with the music he was raised with. “Even in high school I was writing about creating some new form of universal music where you could recognize the different traditions somehow, but together they would create something new, something unifying,” he says.

A top student at the Casablanca American School, Belyamani graduated as valedictorian and was accepted to Harvard University in 1995. Once he started college, Belyamani was pursuing a bachelor’s degree in social studies, but he gravitated toward music, taking classes in jazz, ethnomusicology and composition. Composing music thrilled him—until his sophomore composition class where, after writing and scoring a piece for a full orchestra for the final project of the semester, the performance was cancelled because of a snowstorm. Realizing that writing for orchestras meant needing to have orchestras at his disposal, Belyamani left the class discouraged.

At around the same time, however, his roommate introduced him to electronic music, compositions created on a computer using a MIDI interface and banks of sound samples. “I realized I could hear my music without needing an orchestra at all,” he says. “This kind of music was like having a conversation with the orchestra that never played my composition. I didn’t have to ask, ‘Can you play that? Can you make that louder?’ I could just do it.”

But electronic pop left him cold. Until, that is, like many college students of the era, he first heard Icelandic singer Bjork’s heavily electronic 1997 album, Homogenous. “For me, music needed to have more breath. It’s more about humanity, about imperfections,” he says. Bjork’s use of computers to create “rhythms that were alive and that blended seamlessly with string sections and with live vocals so the electronic and acoustic were harmonious. I’d never heard anything like it.”

Remix-Culture exists to “explore the ties between acoustic and electronic music, between the ancient, the past and the future.”

—Hatim Belyamani

Once he was in Casablanca, he borrowed his mom’s car, grabbed a couple of microphones and a camera he’d brought with him and set out for Khenifra, a northern central city surrounded by the Atlas Mountains. The destination was not random. His younger brother, Amino, a professional musician who plays in a Gnawa band, had been issued an invitation to meet famed Amazigh singer Mohamed Rouicha. Rouicha had died earlier in 2012, but family members furnished Belyamani with contact info for the people who could put him in touch with other folk musicians in the region. In Khenifra, Belyamani started with a local music shop owner. He’d hoped the man would simply point him toward the musicians Belyamani hoped to record, but this was out of the question, the man told him. Instead, he gave Belyamani a crash course, not only on the music but also the Amazigh culture that had created it. Once the shop owner was certain Belyamani knew enough to begin to understand it, he introduced Belyamani to a local group of players to film and record.

Upon returning from Morocco, Belyamani landed in New York City and impulsively applied for a small grant to create an art installation at Priceless, an annual multi-day music and arts festival held in Belden, a small town tucked into the Sierra Nevada foothills of Northern California. He was shocked to discover he’d won the grant. Tasked with creating something that would engage passersby for the 2012 festival, Belyamani drew on his Khenifra recordings and photos to design an interactive music and image program that allowed people to play with the recordings and images to create their own remixes of the original songs. The concept was a hit with the festival crowd, and suddenly the germ of an idea was planted.

“I am so grateful for their commitment to ... providing artists like myself with the tools to create and express ourselves in new and exciting ways.”

—Khalil Mounji

Soon he was back in Morocco seeking out more musicians around the country to film and record. “I realized I left Apple to do this, to follow my heart, to be who I want to be,” he says. “If I’m not going to do it now when I have the resources and I have made the time, then when?” So he committed, bringing along a small recording and video team that he paid by drawing on his savings.

Tyler Wood, a college friend who worked as a sound engineer on that trip, says he was amazed by how open people were to being recorded and filmed, but they had to be ready to start at any time. “No one wanted to do a second take,” Wood says. “We didn’t ever really do a sound check. Even when we went to check the mics a group would start up and do a 20-minute, mind-blowing performance, and you had to just capture that. They weren’t going to do it again.”

That was only the first trip. Over the next few years, Belyamani footed the bill to film about a dozen groups from around the world until he established Remix⟷Culture as a nonprofit in 2016. In addition to Morocco, the team ventured to Brazil, China, Hungary, Lebanon, Albania, Reunion Island, among other places. Back in the US, Wood mastered the audio that Belyamani and other team members paired with visuals to create short clips remix artists could use for free. Eventually, they started posting these clips online.

Khalil Mounji, a Moroccan remix artist and Gnawa performer who used samples to create his 2021 fair trade remix, “Asunfu,” found himself enamored by the samples Remix⟷Culture offers. “Their website is a treasure trove of creativity,” he says. “I am so grateful for their commitment to preserving and celebrating the beauty of cultures from around the world, and for providing artists like myself with the tools to create and express ourselves in new and exciting ways.”

The pandemic curtailed Remix⟷Culture’s globetrotting beginning in 2020, but it also made Belyamani realize that Brooklyn is packed with musicians from around the world, gathering locally- based groups that play traditional and folk music in small venues and recording spaces only miles from his New York home.

Turkish violinist Eylem Basaldi participated in a recording done in a Brooklyn art space last year. “It was like a few friends coming together and just playing,” she says. Basaldi also appreciates the care that was taken in the recording session has extended through the process of getting the samples on to the website. “I really believe in what he’s trying to do, and if I can be part of it, even in little snippets, that’s great,” Basaldi says. “I think it’s important to get this music out into the world and to make it available, and they do that with these samples that are put together with a lot of thought and awareness.”

That’s also a crucial part of the intentions behind Tanfis.

As a drummer snakes his way through the crowd that November night, Belyamani grins again before plunging himself into the gyrating audience. The show has come off without a hitch, and even though he can’t determine if anyone else has experienced a spiritual release, Belyamani is ecstatic.

After all, not only has he found a way to show people the possibilities to be found in using Remix⟷Culture’s samples, he has also realized that long-held dream of finding a way to blend many different types of music into a unified experience.

Although this was the first Tanfis performance, the crowd’s reaction assures him it won’t be the last. The possible ways to use Remix⟷Culture’s sample archives keep expanding and the nonprofit is proving adept at garnering support—in May the organization won a $25,000 National Endowment for the Arts grant to fund more projects and performances. “We’ve come a really long way,” he says. “I feel like something is different now, too. For the first time, Remix⟷Culture is building something solid, and we’re poised to be able to go further and deeper into our work.”

About the Author

David H. Wells

David H. Wells is a multi-media photojournalist based in Rhode Island and a regular contributor to AramcoWorld; he also publishes a photography-education forum at www.thewellspoint.com.

Kay Hardy Campbell

A former resident of Saudi Arabia, freelancer Kay Hardy Campbell writes often about Middle Eastern culture.

You may also be interested in...

A Vocal Appeal To Safeguard Albania’s Iso-Polyphony

Arts

For centuries iso-polyphony, a style of folk singing, has chronicled Albanian life. The songs are part of a rich tradition, vital to weddings, funerals, harvests, festivals and other social events. Indeed, a Ministry of Culture official dubs it “the autobiography of a nation,” a means for the preservation and transmission of different stories. Recently, crowds gathered for the National Folklore Festival in the “stone city” of Gjirokastër, demonstrating that interest in iso-polyphony remains high. The challenge is getting younger generations to engage. But some are taking up the call.

Bridging Lyres and Lutes

Arts

History

For more than 4,000 years. people have adopted, adapted and adjusted the lute, resulting in its countless variations. Along the way. some innovations have proved both consequential and simple.

Berlin’s Transcultural Jam

Arts

Culture

A musical wave has been swelling for a decade in the German capital, which one local analyst now calls “the city of choice for a new generation of cultural talent from the Middle East and North Africa”—part of the greater demographic shift that has made people of Arab backgrounds Berlin’s fourth-largest ethnic-identity group. In street jams, clubs, studios, concert halls and online, new mixes of musicians are blending notes and ideas into genre-bending, transcultural fusions. “What we as artists in Berlin can do is tear down the borders in our head and invite others to do the same,” says musician Jamila Al-Yousef.