A Vocal Appeal To Safeguard Albania’s Iso-Polyphony

- Arts

- Music

11

Written by Tristan Rutherford

Photographed by Ilir Tsouko

As dusk begins to settle into the night, Arian Shehu dons his gold-trimmed waistcoat and century-old iron belt, minutes before taking the stage and kicking off his country’s largest folk festival. With everything in place, Shehu, known as the godfather of iso-polyphonic singing, strides onto the stage to a wave of applause from the mostly Albanian opening-night audience. Shehu opens with the thunderous notes of a folk song that he later says can be traced back more than 2,500 years. Soon, eight other singers clustered around him join in. The ensuing group chant is captured and shared by a thousand smartphones held aloft in Gjirokastër’s 13th-century fortress.

“When I sing with my soul and it goes well, I tear up,” Shehu says.

More than 1,200 artists and thousands of folk-music lovers travel across the globe to attend the 2023 National Folklore Festival, an eight-day celebration of Albanian iso-polyphony and other folk music that is held in Gjirokastër, the ancient “stone city” in southern Albania, every five years. Due to COVID-19, it has been eight years since the last festival. The audience buzzes with excitement.

Yet backstage a threat hangs in the air. This music that records Albania’s history is being forgotten by younger generations who continue to leave the country in record numbers or who show little interest in learning from Shehu and other celebrated artists, even if they do stay in Albania.

This must change, says Vasil Tole, an Albanian composer and ethnomusicologist who doubles as head of Albania’s Department of Cultural Heritage in the Ministry of Culture. Otherwise, these societal songs that have been “the autobiography of a nation” may pass into oblivion, he warns.

Shehu and other musicians share Tole’s concern.

The interest is there, Tole says. The challenge is getting the younger generations to not only enjoy the music but to engage with it and learn its history. “Our songs record profound things in life like lamentation, respect for the dead, love, emigration and heroes,” says Tole. “Polyphony is vital to Albanian culture.”

Backstage, a festival organizer yells “pesë minuta!”—five minutes—as a young female group of about 20 races to pull on gold-trimmed boots, blood-red headscarves and floral petticoats that took 12 months to embroider. When the women gather on the stage, they, too, are greeted by hundreds of cellphones held aloft. These recordings will soon be uploaded, shared and even remixed by Albanian enthusiasts here and around the world.

This unique singing style consists of a lead singer calling out a sort of recitative and two-, three- and four-part harmonizing around him. Historians believe this tradition dates back to the Illyrians, an Iron Age society that inhabited the western Balkan Peninsula for more than a thousand years. “The hypothesis is that iso-polyphony predates the Romans or any other of Albania’s many invaders,” Tole says.

Thirteen-year-old Orion Demirxhiu is taking up the mantle of iso-polyphony for the next generation; Ilir Loku, 40, wears a traditional costume and carries a broadsword; young women, both singers and dancers from the Albanian minority in Montenegro, take part in the traditional pastime; and dancer Flavio Xhafer, 22, is performing at his third festival as part of the Albanian National Ensemble. “It’s my passion to present my nation,” he says.

Over the centuries, Illyrian shepherds and farmers, from whom Albanians descend, honed the craft. They would holler across valleys of the eastern Balkans, covering much of present-day Albania and bordering Greece, North Macedonia, Kosovo and Montenegro. The group’s iso-polyphonic chant is initiated by the “starter,” or ia merr, who passes her tune to a second singer known as a “turner,” creating a harmonious polyphony. She “turns” her solo to a third “thrower,” or a fourth or fifth shepherd who would join in the iso, or drone, which completes a pitch-perfect note struck by a backing ensemble.

Nature evolved the music further. Harmonies mirrored gushing rivers. Iso drones mimicked thunder. Cowbells copied the sound of grazing animals. Although iso-polyphony predates musical instruments and uses a pentatonic scale, the simplest five-note schema, their slow introduction—including bagpipes, accordion and violin—added extra “voices” to the mix over the centuries. “The instruments generally imitate sounds from nature,” explains Tole.

Albania’s lofty topography served to protect the art form from the cultural impacts of lowland invaders, while further influencing the style. For example, singers from mountainous areas like Gjirokastër tend to influence the style with louder and deeper tones that help the melody carry farther. And vocalists from seaside destinations like Vlorë, Albania’s third-largest city, tend to sing at a quieter yet higher pitch.

Before Albanian written history, a recent occurrence, iso-polyphony became a millennia-old chronicle as the songs were vital to weddings, funerals, harvests, festivals and other social events. “It served as a means for the preservation and transmission of different stories, tales, narratives,” Tole says. “For example, some Muslims sing the history of their religion in polyphonic songs.”

After Europe’s strictest form of communism took hold in Albania, with a communist government ruling the country from 1946 to 1991, iso-polyphony became even more popular. Authorities deemed singing folk music a positive national pastime while banning foreign music—alongside beards, long hair, overseas travel and Western movies. For decades the capital’s music station, Radio Tirana, played only traditional Albanian music. In a land devoid of The Rolling Stones and Bon Jovi, iso-polyphony thrived.

Shehu made his performing debut at the Gjirokastër National Folklore Festival in 1978 at age 16. Born in Gjirokastër, Shehu was inspired to take up singing by his mother and father (his father was also a singer of some repute). The experience of standing onstage that day transformed the then-teen’s life, when all the hours of listening and harmonizing with other singers in his community really paid off. “At the castle of Gjirokastër, for me, it was a special moment,” Shehu recalls. “Since then, I never missed any festival.”

“There was a bit of a gap where youngsters didn’t understand or care about iso-polyphony.”

— Edit Pula

Communism collapsed in Albania in 1992, sparking a cataclysmic revolution. The effect on iso-polyphony was twofold. “Teenagers could suddenly listen to any pop music,” remembers Edit Pula, a music producer and artistic director who grew up under communist rule. Though iso-polyphony had been used for two millennia, it vanished from [Albanians’] ears. “We even danced to Arabian music—anything that was different,” she says.

In post-communist Albania, the youngest of Albania’s three million population went abroad to find work. According to the United Nations International Organization for Migration, by the following decade, more than 700,000 Albanians had emigrated.

At the same time, long-standing singing ensembles separated, music schools shut down and even teaching methods started to be forgotten. “Our system broke along with all our industries,” Pula says. “There was a bit of a gap where youngsters didn’t understand or care about iso-polyphony.”

The fight to safeguard iso-polyphony began in the mid-2000s. Realizing the form was in decline, Tole prepared a dossier comprising every facet of the music style, from its techniques to its history, helping secure a place for Albanian iso-polyphony on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list by 2008. He compares it to jazz in America. “Both are communal forms of improvisatory music,” he says.

The UNESCO status raised the music’s profile, and soon tourists began showing up in towns specializing in iso-polyphony. “When foreign tourists come and visit Butrint or Gjirokastër,” only an hour’s drive apart, explains Tole, “what do they ask to see? A group of polyphonic singers.”

At the same time, the advent of YouTube, smartphones and other technological innovations made it possible for anyone to begin preserving the music. Streaming has evolved the art electronically, with Albanian deejays like RDN mixing ambient dance beats to help modernize and popularize iso-polyphony tracks for a lost generation. This practice is not without controversy, however. “Iso-polyphony is the voice of our ancestors,” warns Tole, “so you can’t kick it too much.”

While deejays are remixing, others like septuagenarian singer Shkelqim Beshiraj have begun uploading YouTube videos of themselves bellowing from rural mountaintops, with some logging as many as 1 million views. He traveled from Italy, where he is based, to join the 2023 Gjirokastër festival. “This year is the biggest festival yet,” he says.

Orion Demirxhiu, aged 13, also records videos of himself performing and looks forward to his own performance at the festival later in the evening. “This tradition is important,” asserts Demirxhiu, who claims that iso-polyphony beats Netflix any day. “Every time we go on a family gathering, in a car or a cafe, we always sing the most beautiful songs you’ve ever heard.”

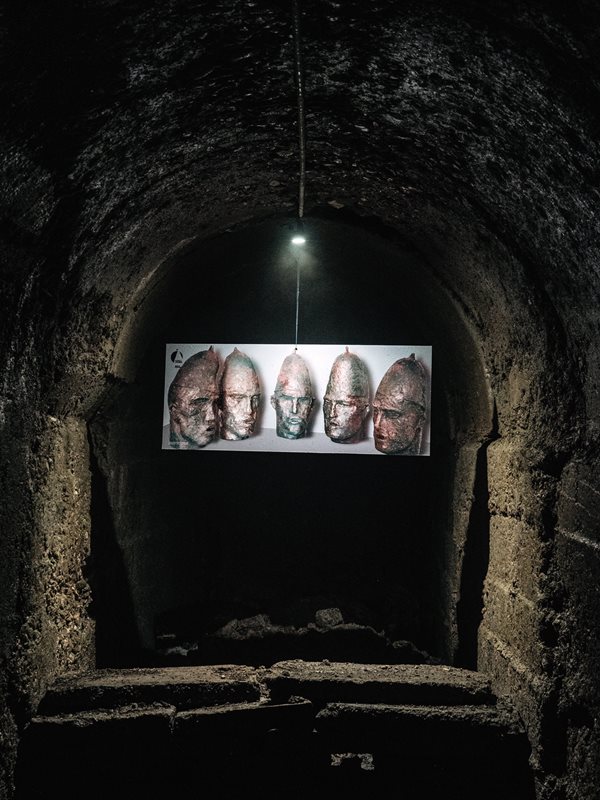

Pula, the music producer, presides over the most recent beacon of hope. In 2022, she opened an iso-polyphony museum beneath Gjirokastër’s Bazaar Mosque, an 18th-century mosque that sits directly below the castle alongside a network of subterranean Cold War-era bunkers. One section has been turned into a sound tunnel that streams iso-polyphonic tunes into a dark, dank chamber. The museum and its tunnels are all part of her quest to spark people’s interest by making music more accessible.

“This tradition is important. Every time we go on a family gathering, in a car or a cafe, we always sing the most beautiful songs you’ve ever heard.”

— Orion Demirxhiu

Pula admits that preserving the traditional musical style remains a challenge. “Twenty-year-olds are streaming what’s in fashion like Dua Lipa,” the British-Albanian pop star whose Kosovo Albanian parents fled the Balkans in 1992. Meanwhile, the songs of Shehu and other master singers are on a few youngsters’ playlists. Pula hopes at least her visitors “come out of the museum knowing an Iso-polyphony for Dummies.”

Of course, not everyone is positive about the music’s digital evolution. One of the principal themes of iso-polyphony is expressing lamentations for times gone by. For some, even the videos proliferating online signal something has already been lost.

As Gjirokastër prepares for night two of the festival, Shehu is in a lamentable mood. Sitting on his balcony terrace looking across to the Gjirokastër fortress, he explains the sorrowful expression of iso-polyphony comes out of life experiences. “Perhaps you’re at a wedding,” he says. But instead of lyricizing happy thoughts, “you see a mother crying as her daughter moves to a new home. Everyone who feels their soul can write verses.”

The pairing of modern music with iso-polyphony distresses Shehu. In 2023, the grand master came across a TikTok video through one of his daughters (two of his other children have emigrated to the US) that spliced his songs with contemporary beats. “The new generation hears remixes and copies things,” he says. “I dedicated my life to creating 500 new pieces of music. This next generation is copying, not creating.”

So, the art, as Shehu sees it, cannot develop via technology alone. But it continues on in other ways.

In the Gjirokastër fortress, Ilir Loku is warming up for night two of the festival. He is dressed like a handsome brigand from Hollywood’s central casting and carries a broadsword and a bow. Aged 40, Loku is part of the roughly 30,000-strong Albanian diaspora in Montenegro, where his ethnic group once faced discrimination. This only made Loku and the other performers in his troupe more determined to preserve the tradition. “We could only sing these songs at home,” he says. “People fought for us to wear these costumes.”

Kristaq Gerveni, a 64-year-old submariner from the city of Vlorë, some 130 kilometers northwest of Gjirokastër, has experienced firsthand how this music survives in the Albanian diaspora. His family originated in the Korçë region, along the Albania-Greece border, he says, before his Aromanian-speaking community was deported during a Balkan conflict over two centuries ago. Twenty family members are present this evening, with several about to go onstage. The reason is simple: “Our iso-polyphonic songs are in the language of our ancestors.”

Near midnight an impromptu group unites in song outside Gjirokastër mosque. After the starter and turner sing the polyphonic verses, anyone can join in the chorus, even if they don’t know the words. “The magic of iso-polyphony is that it doesn’t have a lot of verses,” Tole says.

For Shehu, the magic resides in the very timelessness of this age-old art form. He has a theory that tradition comes from a place everyone understands. Maybe it started with a single Albanian walking alone at night, he imagines. When others joined in, that first person would know they had an entire community at their back. “You’d sing when you’re scared,” he says. “And your song was reassured by a second person.”

Although Shehu worries about the future of iso-polyphony, he tries to focus on the music. “For the next generations it’s difficult,” he explains. “But it is part of me, and as long as I have my eyes open, inshallah, I will do it.”

About the Author

You may also be interested in...

America's Music of the Nile

Arts

The Nile river has been used as motif, a metaphor or both in popular culture, most prolifically in music in the United States for more than 125 years. The most notable uses of the Nile arose during the jazz period, which peaked in the second half of the 20th century and continues to this day.

Tinariwen's Sahara Blues

Arts

Coming out of the struggles of post colonial desert Africa, Tuareg band Tinariwen adapted blues rock ‘n‘ roll guitars to North African traditions. The result has been nearly four decades of a sound that has inspired an entire genre of “desert blues,” in which themes of loss, home, hope and unity transcend language for audiences around the world.

Record, Remix, Repeat

Arts

For more than 10 years, Moroccan native and New York resident Hatim Belyamani has focused his non-profit Remix⟷Culture on offering digital sample and remix tools that give exposure and preserve access for traditional acoustic music around the world.