Creating Harmony Through Tradition in Japan

- Arts

- Migrations

- Foodways

- Architecture

14

Written by Matthew Teller

Photographed by Naoki Miyashita

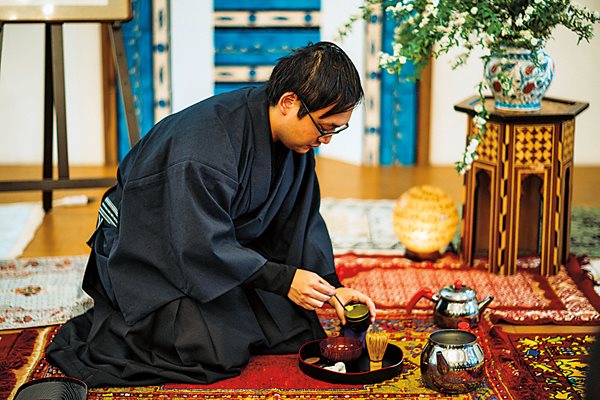

With the precise, measured actions of a Japanese ceremonial master, Qayyim Naoki Yamamoto carefully turns a small bowl of freshly made tea twice through 90 degrees. He then presents it to a kneeling recipient who takes the bowl in both hands and, with a bow of the head in respect, retreats to sip it thoughtfully.

Yet despite his skill, Yamamoto is not a tea master. A professor of Islamic studies at Marmara University in Istanbul, Turkey, he is an influential figure shaping Japanese Muslim society. His tea ceremony is taking place not in a traditional tea house but before a seated audience ranging from students to elders in Tokyo’s main congregational mosque. At the age of only 33, Yamamoto has developed what he calls an “Islamic tea ceremony” as an experiment, an innovative public workshop in which new links of understanding can be forged between Japan’s roughly 0.1-percent Muslim population and the rest of the country’s people, almost all of whom follow Buddhism and Japan’s homegrown religion, Shinto.“The point is to help people acquire the power of interpretation, the intellectual muscles of critical thinking and critical understanding of this world,” Yamamoto says. “We, as Muslims, can contribute to the prosperity and diversity of Japanese society.”

In a Zen Buddhist tea ceremony, he continues, the tea master will ask guests to contemplate a hanging scroll decorated with a character or phrase drawn from ancient Chinese poetry. But Yamamoto contends that the same device can be interpreted in other ways: In this tea ceremony, he displays a scroll in Chinese characters showing the word muga (nothingness), which refers to the annihilation of ego, alongside another scroll with a beautifully fluid example of Ottoman Turkish calligraphy forming the word hiç, which also means nothingness. The visual and philosophical interplay between the two is striking.

Yamamoto says that by using an Islamic hanging scroll, he “wants to show a harmony between Japanese traditional culture and Turkish traditional culture.” He is wearing a kimono—a traditional loose, wrap-around robe—and he relates it to similar garments worn in Arab societies. He carries a fan, a highly symbolic item usually printed with a Zen poem used in a tea ceremony to define respect between master and disciple and to mark a division between the natural and the supernatural—but Yamamoto’s fan instead features classical Islamic poetry, drawn from the 18th-century Chinese Han Kitab tradition. One object synthesizes multiple cultures.

Islam’s history in Japan is almost entirely recent, although there are records of contacts between Muslim cultures and the peoples of what is now called East Asia over more than a millennium. Early Muslim sources mention Waq Waq, an island located near China that, according to ninth-century Persian geographer Ibn Khordadbeh, was wealthy enough to export gold and ebony. Some scholars have theorized that Waq Waq may have been Japan, though Java or Sumatra—or another of the islands making up modern Indonesia—may be more reliable candidates.

Stronger evidence of contact is provided by a map produced in Baghdad around 1074 CE by Turkic scholar Mahmud al-Kashgari, which depicts an island named Japarqa lying to the east of China. Sporadic encounters over the following centuries ended in 1603 when Japan’s rulers effectively sealed the country off due to factors such as the expansion of trade and internal domestic political shifts, barring Japanese people from leaving and permitting very few non-Japanese people to enter.

The story picks up again in the late 19th century, soon after Japan had reopened to the outside world. In 1887 Japanese diplomat Akihito Komatsu visited the Ottoman capital, Constantinople. Three years later, the Ottoman Sultan Abdülhamid II returned the compliment, sending the naval frigate Ertuğrul to Japan to consolidate relations—but on its return journey the vessel foundered in a storm off the coast of southern Japan. Hundreds of crew and passengers died. The 69 survivors were supported by Japanese communities and then escorted home by the Japanese navy.

With them traveled Shotaro Noda, 23, a journalist who stayed in Constantinople to teach Japanese to Ottoman military officers. He lived there almost two years, and it is believed he was the first Japanese person to become a Muslim, taking the name Abdulhalim in a ceremony on May 21, 1891. Noda later abandoned his faith, and the first Japanese pilgrim to Makkah seems to have been scholar Kotaro Yamaoka, who took the name Omar after becoming a Muslim in 1909 and went on Hajj the same year.

But the early Japanese Muslims “were nationalists first of all, and that they all devoted themselves, even spiritually, to the cause of the Japanese Emperor,” writes Tokyo University professor Kojiro Nakamura. Yamaoka was in fact working on behalf of Japan’s imperial government to gather “intelligence on the Islamic world,” says sociologist Akiko Komura, even though Yamaoka’s acceptance of Islam seems to have been genuine and lasted to the end of his life.

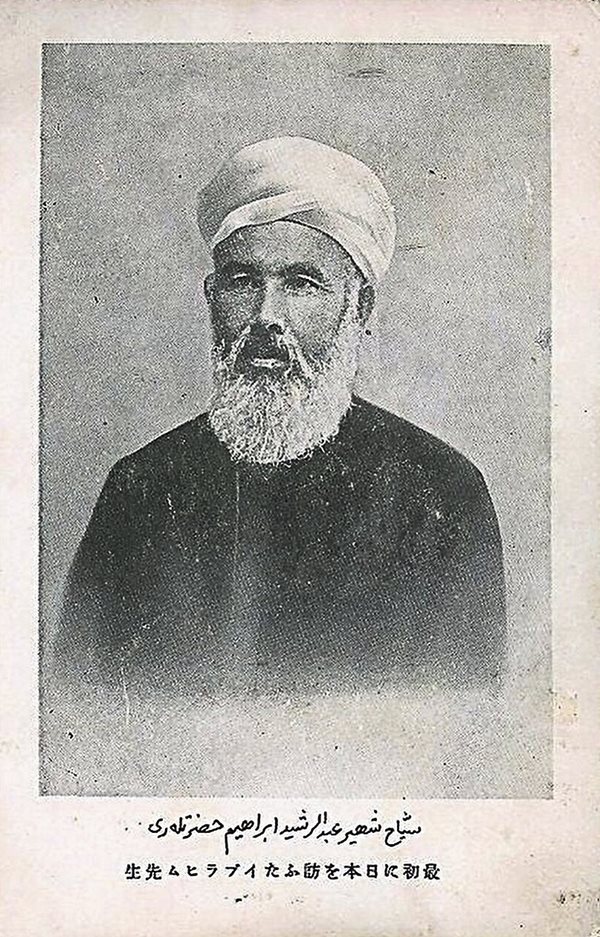

Yamaoka’s inspiration and spiritual guide—who also worked closely with the Japanese authorities—was the Tatar writer and activist Gabdrashit Ibrahim, born in Russia in 1857. Ibrahim traveled widely to Europe, Arabia, around the Ottoman Empire and across Central Asia to China and Japan, speaking publicly and publishing newspaper pieces campaigning for pan-Islamic solidarity and Muslim liberation from Russian imperial rule.

Though Russia’s monarchy fell in the Revolution of 1917, Muslim liberation did not follow, and subsequent hostility to religious observance prompted an exodus of Turkic Tatar Muslims. Within a few years, several thousand had settled in Tokyo and port cities including Nagoya and Kobe, where they added to the small communities of Muslim Indians, Arabs and others. News of their positive reception traveled fast: Accounts of Japanese society in Persian, Turkish, Urdu, Malay and Arabic circulated widely, scholars traveled to exchange knowledge, and import/export merchants did lively business. Under the charismatic guidance of the Tatar rebel commander Muhammad Abdulhayy Qurban Ali, who led a group of followers east to escape Russian persecution, Tokyo’s nascent Muslim community established a school and prayer room in 1927, and the city’s first purpose-built mosque in 1938, where Gabdrashit Ibrahim served as its first imam.

But Tokyo Camii was not the first mosque in Japan.

Less than three hours from Tokyo by high-speed bullet train, Kobe is today a cosmopolitan waterfront city of 1.5 million, known as a major manufacturing center and the home of one of the most flavorful varieties of Japan’s marbled Wagyu beef. Its reputation for openness originates in the decades either side of 1900, when Kobe pioneered global links of trade and culture fostered by expatriate communities of Indians, Chinese, Europeans, Americans and others. The foreigners tended to concentrate themselves in Kobe’s international quarter of Kitano, which was characterized by terraces of ornamented red brick villas gazing down on the port below.

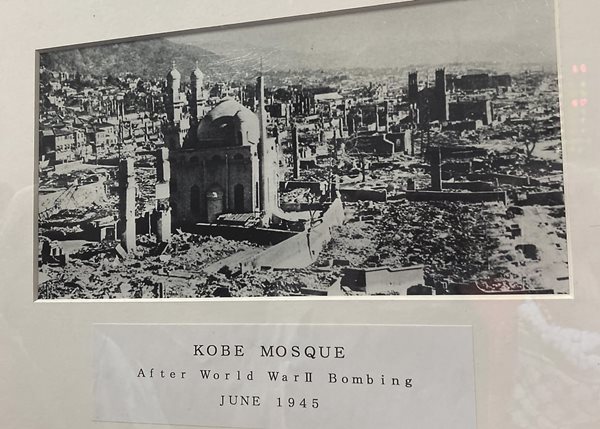

That architectural eclecticism is still on display on a stroll through Kitano’s steep streets. The minarets of Kobe Mosque, established in 1935 shortly before Tokyo’s mosque, still reach above the Kitano skyline of modern apartment buildings, within walking distance of churches, Buddhist temples, Shinto shrines, and a synagogue.

“At that time, Islam was barely known here,” says Mohammed Jaafar, 33, the Pakistan-born imam of the mosque. As he pads, shoeless, along the mosque’s corridors, his shalwar kameez illuminated by sunbeams filtering through yellow frosted windows framed by pointed arches, he describes how the building withstood bombing in 1945 and an earthquake in 1995: Framed photos on one wall show the mosque rising undamaged amid fields of rubble following both catastrophes. Jaafar relates the building’s miraculous survival to the city’s name: One meaning of “Kobe” is “The Door of God”—although the phrase references the city’s 1,800-year-old Shinto shrine Ikuta Jinja.

On a rainy Friday in February, Jaafar stands at the door of the mosque greeting worshippers as they arrive for the midday prayer. The congregation numbers perhaps two hundred, with community origins ranging from Japanese, Malaysian and Pakistani to Nigerian, Uzbek and Uyghur. Several men are each wearing chef’s hats and aprons, having negotiated a brief window of time off work in nearby restaurants.

Reyna Arifin, 19, of mixed Indonesian and Chinese background, has come to pray with her family from the nearby city of Osaka, where she lives in an “open community of Japanese people who are curious about Islam.” As she and her mother, who wears the hijab, discuss their sense of Muslim identity—“strong!” she laughs—her brother Reyhan, 18, joins the conversation. He is studying at a university in Oita, a small city around 500 kilometers west of Kobe, where he speaks of “a sense of treading on eggshells around religious observance—you have to be careful not to overstep social bounds,” he says, because mainstream Japanese society “does not hold to any religion.”

Despite the tens of thousands of Buddhist and Shinto shrines around Japan, and almost universal participation in the rituals of worship, Arifin’s counter-intuitive view is borne out by others. Tokyo management consultant Manae Shimizu, 25, asserts that in general, religion is marginal in Japanese society compared with many other cultures. Ritual at shrines, she adds, is mostly “to preserve cultural tradition.”

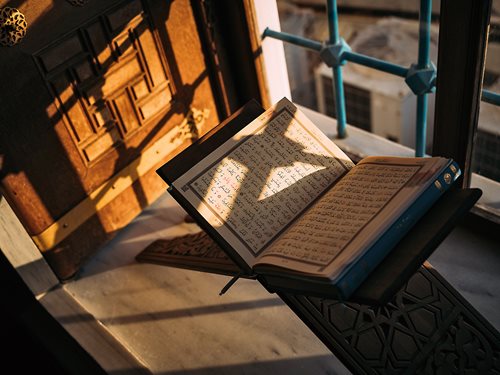

Saeed Sato, 49, director of the Japan Muslim Association, speaks instead of Japan’s “department store of religions,” from which he says people will cherry-pick appealing elements of Buddhism, Shintoism, Christianity, even humanism. “They prefer to define their worship as habit rather than religion. There is a fear that clarity of expression will raise conflict, so ambiguity is preferable,” says Sato, whose Japanese-language interpretation of the Qur’an was published in 2019.

Left Chef Toshihiro Maki shows the circular halal mark on a jar of alcohol-free vinegar that he uses in his dishes. Grocery stores supplying halal products are opening all across Tokyo, including, right, in the lively Shin-Okubo district.

“Islamic practice is often considered as breaking wa,” adds sociologist Akiko Komura, giving the example of Muslim employees negotiating time off for prayer as sometimes raising hackles for challenging staff solidarity within companies. She acknowledges that the acceptance of diversity in Japan is rising, even if it might mean the majority is merely ignoring the needs of minorities rather than accommodating them.

Nevertheless, where Islam is visible, mainstream interest in the religion and its outlooks appears buoyant.

In the lobby of the Tokyo mosque, public affairs officer Shigeru Shimoyama,

73, is raising his voice to explain the basics of Islam to a group of around a hundred visitors, all Japanese, none of them Muslim. The mosque advertises free weekend tours on its Facebook page, and every Saturday and Sunday similarly large crowds of people show up, Shimoyama says.

At the edge of the group stands Akari Fujimoto, 24. “I saw Islamic architecture in a textbook, which sparked my interest. Then I found we have this in Tokyo too—so I came to see the real thing,” she says, adding that she had never set foot in a mosque before.

Tokyo’s original 1938 mosque survived World War II but, by the 1980s, had become structurally unsound. It was demolished, and its replacement opened in 2000 under the direction of the Turkish government, renamed “Tokyo Camii” (camii, pronounced JAHM-ee, is a Turkish word of Arabic origin meaning mosque). The strikingly ornate building, which stands on an otherwise unremarkable leafy boulevard in the Yoyogi district, was designed in Ottoman style by architect Hilmi Senalp. Its slender minaret and 23-meter dome crown an ethereal prayer hall of white and turquoise marble detailed in gold. For Friday prayers, roughly 500 worshippers cram inside, with another 200 or more praying in outdoor courtyards. The service, including the weekly sermon—delivered in four languages (Japanese, Turkish, Arabic and English)—is live-streamed online.

As Shimoyama leads the visiting group upstairs to view the prayer hall, Muhammet Rifat Çinar, 40, Tokyo Camii’s immaculately groomed Turkish imam, notes that the mosque has been declared a Japanese national monument. “People come here as if to a museum. They see it as a site of cultural interest,” he says.

Yet he is adamant that hostility is virtually non-existent. “I never experienced it here. I asked former imams and they say the same. It’s great to live in Japan as a Muslim.”

More than any other recent event, Japan’s preparations for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics have led to broader recognition for both Muslims and other minorities. Expecting to be hosting millions of fans from all parts of the world, in the years leading up to the games, public and private sector entities embarked on intensive research into halal food (meaning food that is permitted under Islamic dietary laws). Many company managers “came to the mosque to learn what halal means, and how to cater to Muslims,” says Cinar.

In the end, COVID-19 caused the Olympics first to be delayed, and then staged mostly without spectators—but the advances in understanding and logistics persisted. Tomohiro Sakuma, 58, runs the Japan Halal Business Association, a consultancy firm advising Japanese food producers on halal certification for export. He guides clients through the thicket of regulation and varying quality standards surrounding more than 400 forms of halal certification worldwide, 30 of them in Japan. Gaining certification can open new markets overseas, but a side benefit is improved labelling of ingredients and widening availability of halal food inside Japan. Sakuma is plain about his motivation: “Clients contact me precisely because I am not Muslim, because this is a commercial initiative. They understand I am doing this purely for business purposes.”

That attitude is widespread. Halal food stores are popping up around Tokyo, and are mostly low-key outlets in or near neighborhood mosques, offering basic essentials imported from Asian, African or Arab countries. Hidden away behind Tokyo’s glittering “Koreatown” district of Shin-Okubo, a narrow lane informally known as “Islamic Street” houses a handful of South Asian halal grocery stores and snack outlets. A few hotels around Japan offer halal food, gender-exclusive spaces and prayer rooms for Muslim visitors.

Yet the run-up to 2020 also saw instances of mainstream expansion. Sushi Ken, in Tokyo’s popular historic district of Asakusa, became the city’s only halal sushi restaurant in 2017. It remains so today, and proudly displays its certificates. “Every time Muslim tourists from Malaysia or Singapore visited the restaurant, I would have to explain what ingredients go into the sushi—and they would be so disappointed they couldn’t eat it,” says head chef Toshihiro Maki, 54. “I knew nothing about Islam, and this became a trigger for me to research.”

Sushi is almost all made with fish and seafood. Maki describes how his team first incorporated halal meat into their non-sushi dishes, but then chose to drop meat altogether for simplicity’s sake. Then they eliminated alcohol, by removing sake (rice liquor) from steaming methods and changing suppliers of such key ingredients as soy sauce and mirin (rice wine), which usually contain alcohol. Their gari, slices of pickled ginger served alongside sushi, is now alcohol free.

“Nobody noticed the change,” Maki grins. “I don’t want to break the trust of my long-standing Japanese regulars, and they are so surprised to learn that everything they eat here is halal. My customers are now about half and half, Muslim and non-Muslim.”

Maki acknowledges that halal certification was partly a business decision, but he also points out that chefs will routinely adjust menus for customers with food allergies or dietary restrictions. “It’s the same thing,” he says. “We are respecting and responding to our growing Muslim customer base.”

That growing acceptability of difference is easing decision-making for the small numbers of Japanese people seeking to embrace Islam. No formal count has ever been done, but estimates put the number of Muslims in Japan between 100,000 and 200,000 amid a national population of 125 million. Of them, only a few tens of thousands are Japanese, many of whom became Muslim to facilitate their marriage. For the remainder, the motivation to accept Islam often originates in positive encounters with Muslim individuals. Mosque guide Shimoyama describes how the hospitality he was shown during a stay in Sudan aged 19 overturned his stereotypes about Islam. Hasan Mamoru Hasegawa, 22, speaks of a trip to Indonesia and a homestay with a Moroccan American family in the US For Kyoichiro Sugimoto, 46, it was a university friendship and subsequent invitation to visit that friend in Bangladesh.

Kyoko Nishida, 52, a translator in Tokyo Camii’s publications department, remembers feeling a sense of spirituality as a teenager but being unable to pray. “My faith was like water: I needed something to hold it, and Islam was a good vessel,” she says, while adding with a laugh that her Japanese family still ask little about her religious observance, for fear of hurting her feelings—more evidence of wa.

“Everyone here has a hole inside. As a student I began to think that maybe foreigners fill that hole with religion,” says Abdullah Kobayashi, 36, born and brought up in a traditional Japanese non-Muslim family in the Nagano mountains west of Tokyo, and now imam of Tokyo’s Dar al-Arqam mosque.

“I don’t want to create an exclusive identity. In Japan now we have Pakistani Japanese Muslims, Bengali, Malay, Arab. They are all Japanese, and they are also all Muslims.

—Qayyim Naoki Yamamoto

As Yamamoto’s tea ceremony ends and he swaps his kimono for a suit jacket, he relates how he became a Muslim at the age of 19 after stumbling across a work by one of the few Japanese Muslim women scholars, Khawla Kaori Nakata. The way she “articulated the concepts of divinity and humanity was so profound,” he says.

Yamamoto, an original thinker who sees patterns of commonality across apparently divergent cultures, discusses with enthusiasm how his spirituality “was formed by reading manga [Japanese graphic novels].” He explains how the genre’s formulaic relationships between master and disciple emphasize repentance, learning from mistakes and moral growth. “Western culture focuses on defining your identity, but that’s not enough. Definition is a moment. Japanese culture emphasizes a process. You build your identity by digesting experience with the guidance of a master. That’s the manga method.”

Yamamoto envisions the implications of this kind of cultural synthesis.

“I don’t want to create an exclusive identity. In Japan now we have Pakistani Japanese Muslims, Bengali, Malay, Arab. They are all Japanese, and they are also all Muslims. If we create a narrow definition of “Japaneseness” we cannot cherish this diversity. Academics talk about how there is no similarity between Islam, which is monotheistic, and Japanese Buddhism and Shinto, which are polytheistic. In part, yes. But Islam also has a practical aspect, focused on striving and spiritual training—and that has lots of similarities [with Japanese outlooks].”

As he packs up his gear and heads out to the subway station, Yamamoto adds reflectively: “By adding our Islamic perspective, we, as Muslims, could help preserve and interpret traditional Japanese culture. Maybe we can become best neighbors.”

—

The writer thanks Tokyo-based journalist Makiko Segawa for her help in research and interpretation.

About the Author

Matthew Teller

Matthew Teller is a UK-based writer and journalist. His latest book, Nine Quarters of Jerusalem: A New Biography of the Old City, was published last year. Follow him on X (formerly Twitter) @matthewteller and at matthewteller.com.

Naoki Miyashita

Naoki Miyashita is a Tokyo-based freelance photographer and filmmaker. He specializes in documentaries that convey traditional culture, crafts and other local attractions.

You may also be interested in...

The Bridge of Meanings

History

Arts

There is no truer symbol of Mostar, Bosnia-Herzegovina, than its Old Bridge. The magnificent icon of Balkan Islamic architecture was destroyed during the 1992–’95 war—but not for long. Like the multicultural workforce that produced the original hundreds of years earlier, a broad team of architects, engineers and others came together immediately to plan its reconstruction. This summer marked the 20th anniversary of the bridge’s reopening.

Gahwa Renaissance

Food

Arts

Preparing, serving and sipping gahwa—the Arabic word for coffee—is a ritual steeped in centuries of hospitality. In December in Abu Dhabi, the inaugural Gahwa Championships honored not only tradition but also innovation.

Meet Me at the Mudhif

History

Arts

Dozens of volunteers joined together in Houston, Texas, to construct a mudhif, a reed structure dating back 5,000 years to the Mesopotamian marshes of southern Iraq. To this day the hut serves as a town hall for Marsh Arabs to meet with their sheikh. In Houston, it also served as a meeting place--for some of the city's 4,000 Iraqis and their fellow Houstonians to share insights into an ancient society and gain a sense of community.