Gahwa Renaissance

- Food

- Arts

- Foodways

Written by Shaistha Khan

Illustrated by Teresa Abboud

As Zayed al-Tamimi’s brass pestle hits the mortar, its rhythmic clink resounds with the crunch of coffee beans through the hall of the Abu Dhabi National Exhibition Centre. On a display screen above him, closeups of his motions attract the eyes of coffee professionals and enthusiasts. Watching most closely is the panel of four judges.

Al-Tamimi has traveled from Iraq to the capital of the United Arab Emirates (uae) to compete in the first-ever Gahwa Championships, held in December. He is preparing a signature pot of gahwa—the Arabic word for coffee—as he vies for honors in the category of Sane’ Al Gahwa, (literally, “Maker of the Coffee”). As he drops thick pods of cardamom and delicate threads of saffron into the mortar to crush with the beans, he fuses all he has learned about centuries-old Arab coffee-making.

A later competition includes Dubai barista Louie Alaba, who offers the judges his cold-brew “gahwaccino” that uses fig, chili and cinnamon. As the competitions hit a stride, attendees discuss the importance of coffee-making across the whole of the Arab world, and how it is not just a matter of a dark- or light-roast beverage served with optional sugar and milk. Arab gahwa is a ceremonial affair, each pour symbolic of the historical and social significance of coffee drinking and an embodiment of hospitality. Coffee is synonymous with Arab hospitality.

In the uae, 1-dirham coins pay homage to coffee culture by showing gahwa’s most time-honored symbol, the dalah, or the traditional Arab coffee pot, with its wide, stable bottom, elongated handle, finial lid and gracefully thin, beak-like spout. Across the Arabian Peninsula, it is not unusual to see a giant-sized dalah erected as public art in the middle of a traffic roundabout.

In his 1982 poem “Memory for Forgetfulness,” the late, celebrated Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish described the first cup of morning coffee as the “mirror of the hand.” He continued: “And the hand that makes the coffee reveals the person that stirs it. Therefore, coffee is the public reading of the open book of the soul. And it is the enchantress that reveals whatever secrets the day will bring.”

Eid Bin Saleh Al Rashid of Saudi Arabia’s Royal Hospitality House Group, and one of the supporters for the unesco designation, emphasized coffee’s importance for the future of culture in his country, “given its symbolic meaning for national identity and in order to preserve and pass this element to younger generations.”

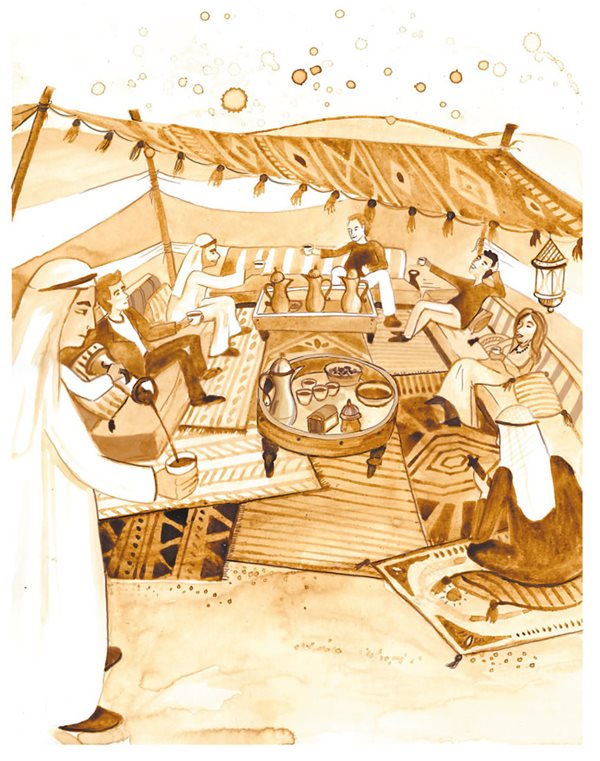

In the desert at the eastern edge of the vast Rub’ al-Khali, heritage guides Waesam Fathalla and Ali al-Baloushy are doing just that. They share centuries-old coffee traditions with tourists, in much the same way their tribes shared with visitors centuries ago: out under the stars, sheltered by a tent, sitting with friends on floor cushions.

Like all good gahwa, they begin with green, unroasted Arabica or robusta beans. Over a makeshift pit of hot coals and sand, Fathalla roasts the beans in a shallow, circular pan with a handle long enough to keep his hands safely away from the fire. The beans bounce back and forth revealing a golden-brown shade and a faint floral aroma. Fathalla explains that while Saudi tradition favors light, blonde roasts, Emirati purists favor darker roasts. Once the beans are ready, they’re removed from the fire and ground into powder using a mortar and pestle. Water boils in a dalah, and nutmeg, clove or cinnamon is added before the coffee.

“Emiratis don’t use too many spices in their gahwa. That way, the natural flavor of the coffee can really come through,” Fathalla says as he grinds the coffee beans.

Throughout the centuries, coffee has been a unifying drink, something to do with family and friends old and new. The spices and flavoring in it can signal one’s economic status, level of respect for a guest, or both. Coffee recipes with saffron and rose water demonstrated wealth and regard for a guest most clearly.

He adds the coffee powder to boiling water and leaves it to bubble for a few minutes. Then he removes the dalah from the heat and allows it to rest, so the coffee grinds settle at the bottom. He then pours from it into another dalah with a filter, and then again into a smaller, ornate serving dalah.

Coffee Cultures

Al-Baloushy begins to explain the role of the gahwaji or server of the coffee, as his assistant begins pouring. The gahwaji holds the dalah in his left hand and balances in his right hand a stack of finajin (handless cups; one cup is a finjan). He gently clinks the cups together to signal the coffee is ready.

Although there are regional preferences and variations in both the preparation and serving of gahwa, the basics of the ceremony remain much the same from place to place.

Al-Baloushy tries the first cup to determine if the coffee is suitably tasty. Then he begins serving the first of three rounds. The first guest cup is al-dhaif, and it cannot be refused without risking insult to the hosts. The coffee is a gift, the men explain, and it establishes trust. To each guest as the gahwaji hands out the cups, al-Baloushy says, “You are welcome.”

The heart of the ceremony, he says, is hospitality, a cherished Bedouin value. As nomads, Bedouins often lived in harsh conditions with scarce resources. They relied on reciprocal generosity among the communities and tribes they encountered. Still today, any traveler or visitor, as was the custom of their older tribesmen, is always hosted, sheltered and fed for three days and three nights with no questions asked. All visitors receive a welcoming cup of coffee; simply placing a dalah atop a fire pit is invitation enough for anyone to join.

The second cup he serves is al-kaif, for enjoyment and pleasure. Finally, al-saif—literally the cup of the sword—is served, traditionally when the parties have established a protection deal between them—a promise to defend one another in the event of threats against their people.

It is also significant that the gahwaji first serves the most important person in the majlis, or social seated assembly. Usually, al-Baloushy says, this is the eldest person or a guest of honor. Then he serves the remaining guests, beginning with those on the right of the guest of honor.

“There are many hidden messages in the way we prepare and serve coffee,” al-Baloushy explains.

As guests sip, they can politely communicate a message without offending or embarrassing others in the group. For example, he says that filling a guest’s cup two-thirds full means you are welcome to stay. If, however, if it is served full to the brim, this indicates the guest may not be so welcome.

“So you drink and leave,” he says.

Placing his own finjan on the ground, al-Baloushy demonstrates that this gesture communicates the guest has an important matter to discuss or a request to make of the host.

“If the time is right, I will talk to him and give him my full attention. If he is satisfied with my reply, he will drink the coffee. If not, he will leave the majlis,” al-Baloushy says.

The gahwaji remains standing to keep an attentive watch on everyone’s cup. Shaking the finjan sideways is the acceptable way of declining another cup.

Abdullah Khalfan al-Yammahi, a heritage expert and author of Etiquette of Gahwa Serving in the uae, explains how coffee brings together people of different ages, social classes and tribes.

“We sit together to discuss and debate. We talk about anything and everything,” says al-Yammahi, who is one of the four judges at the Gahwa Championships. “A dalah is seen as a living entity because it is present in our happy occasions and in sad ones.”

As al-Tamimi replicates the coffee ceremony during the Sane’ Al Gahwa competition, the judges also quiz him on etiquette.

“There are more than 44 adab [etiquette rules] of serving gahwa and more than 22 rules of receiving gahwa,” al-Yammahi explains. This is why it is important that younger generations learn how to interact with others through exposure to the majlis and its rituals. “Something as simple as bending forward to serve is an act of respect and demonstrates morals,” he says.

Khalid Al Mulla is owner of the Dubai Coffee Museum, national coordinator for the country’s chapter of the Specialty Coffee Association, and a promoter of regional and international coffee-culture preservation.

“The coffee business is all about education, whether that is bringing gahwa to the forefront of the global coffee industry and making it a mainstream beverage, or preserving culture by serving gahwa at formal events, or educating local customers on fair trade and ethically sourced coffee,” he says.

Al Mulla’s small, private museum in Dubai’s heritage-oriented al-Bastakiya district is one way young people and visitors can glimpse the spectrum of Arab coffee, from its origins to its ceremonies, artifacts, tools and early modern technology.

Mohamed Ali Madfai owns the cafe Emirati Coffee Co, and he observes that everywhere “the coffee bean is the same, yet the culture of brewing and serving is different.” He likens the Arab dalah to the Turkish ibrik, with its iconically wide bottom and slanted handle.

“Just like Vietnamese-style coffee gained popularity in [the Arabian Peninsula] as much as a Spanish latte, with education and promotion, gahwa could become a mainstream drink in cafes around the world,” he says, noting cafes offering traditional Arab coffee report high demand. Modernizing “gahwa culture,” he adds, will not strip away tradition because “tradition lasts longer than gimmick.”

Zainab Al Mousawi, 31, serves cold-brewed traditional Arab coffee in her Dubai cafe, To the Moon & Back.

“I find gahwa incomparable to specialty coffee. As it is brewed with spices, it makes for a special drink,” she says. “Gahwa and specialty drinks each have their own audience, how and when to be served, and consumed.”

Her gahwa uses single-origin beans and a spice mix, and she brews it over ice using a slow-drip method, another way young coffee innovators are fusing past and present as well as regional and international influences.

“Although young people may be influenced by foreign culture or trends, they always come back to their roots,” says heritage expert and author al-Yammahi. “They recognize their heritage and traditions. It makes me proud to see their involvement and investment in this intangible heritage.”

About the Author

Shaistha Khan

Shaistha Khan is a public relations and freelance writer based in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. She writes on travel, food, culture and topics that resonate with multicultural millennials like herself.

Teresa Abboud

Lebanon-born and Atlanta-based, artist, entrepreneur and coffee aficionado Teresa Abboud produced her illustrations for this article using coffee, a spoon and brushes. She is the creator of her “Coffee Time” and “Teresa Afternoon” collections of art, household items and clothing. Follow @teresa_afternoon, and visit www.teresaafternoon.com.

You may also be interested in...

America’s Arabian Superfood

Food

History

In recent years in the United States, dates have been trending as a nutrient-dense, easily transportable source of energy. Nearly 90 percent of US-grown dates are from California’s Coachella Valley. Yet the date palm trees from which they are harvested each year aren’t native; they were imported from the Arab world in the 1800s. Over the years, they have become a part of Coachella’s agricultural industry—and sprouted Arab-linked pop culture.

Of Spice, Home and Biryani

Food

Slow-cooked with meats, vegetables and spices that vary all across the subcontinent of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, biryani “speaks to love, time and patience” for those who grow up with it, and to dazzling, addictive blasts of flavor to everyone else. No wonder it’s a rising global food star.

Albania’s Resurging Cuisine

Food

After decades of decline under communist rule, food enthusiasts—including brother chef and baker Bledar and Nikolin Kola—are pioneering the return of the country’s traditional dishes. Chefs and other culinary aficionados are drawing on Albania’s 500-plus years of culinary heritage to reinterpret the foods of their ancestors. Their efforts are re-establishing traditions that were feared lost.