When the Mountains Trust You: The Photographic Life of Peter Sanders

- Arts

- Photography

Written by Matthew Teller

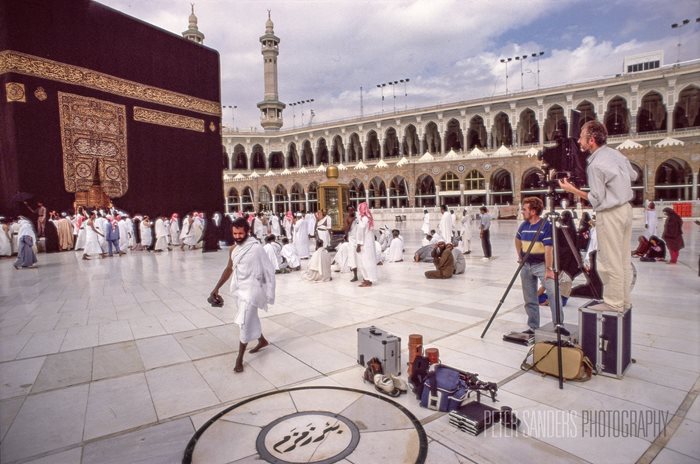

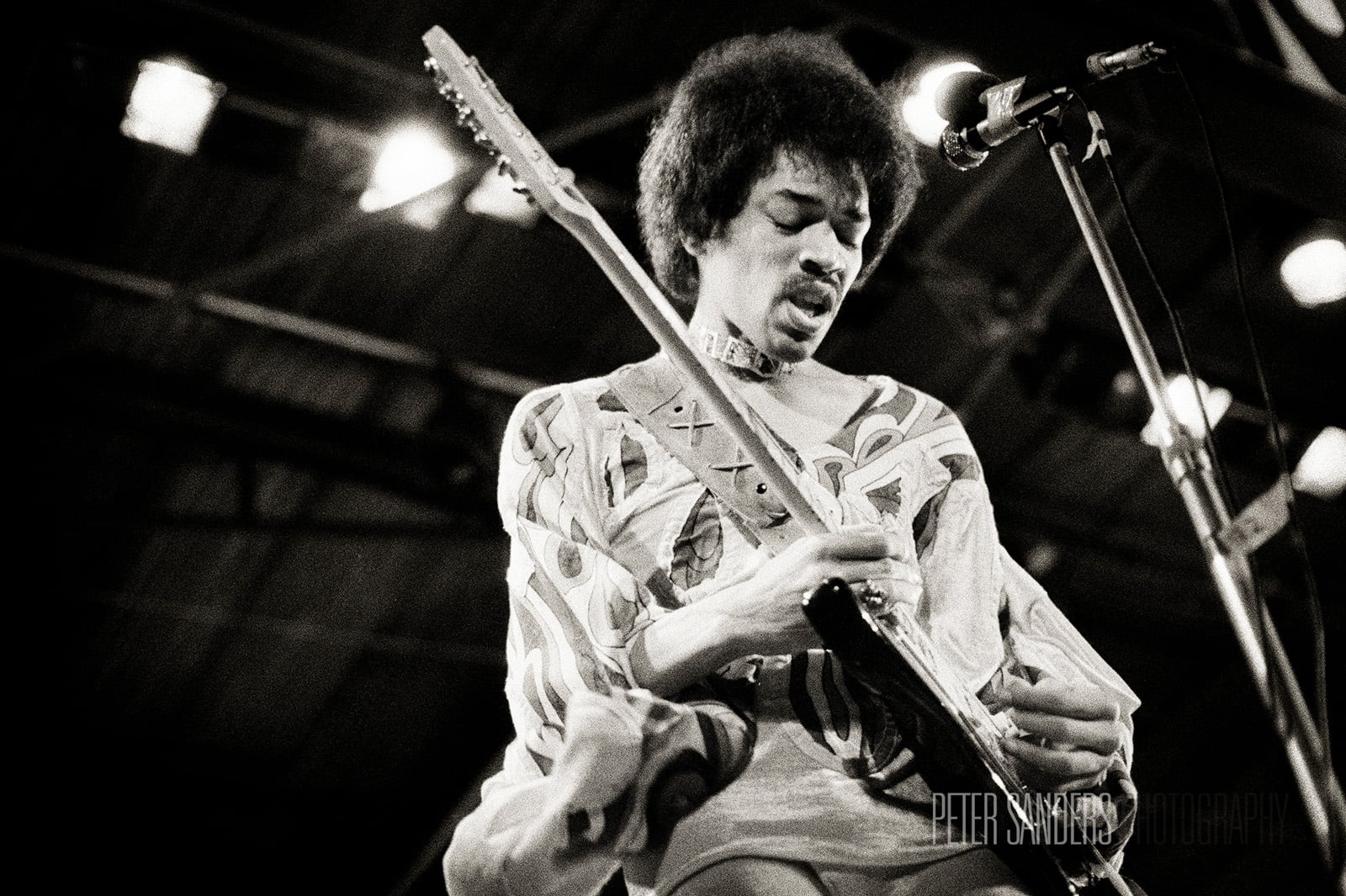

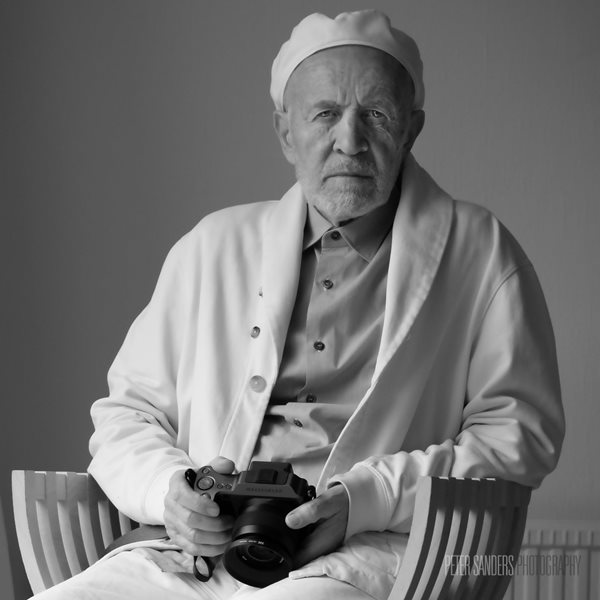

British photographer Peter Sanders was born in 1946. He rose to prominence in the “Swinging London” of the late 1960s, when he photographed rock musicians including Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, The Who and the Grateful Dead. He became a Muslim in 1971, and was one of the first Westerners to be granted permission to photograph the Hajj pilgrimage in Makkah, where only Muslims are allowed to enter. More than 40 years of travel followed, as Sanders photographed communities across the Islamic world. He has exhibited widely and published several books, including In The Shade of the Tree (2007), The Art of Integration (2008)—which The Guardian praised—Meetings With Mountains (2019) and the nine-book box set Exemplars for Our Time (2022). Arab News called his work “a breath of fresh air,” and in 2013 he was awarded a prize in Islamic art by Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, ruler of Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Sanders directs the Art of Seeing collective, which runs photographic workshops around the world, and in June, Sanders presented a retrospective of his career during the Bradford Literature Festival in England.

AramcoWorld spoke with Sanders in Chesham, outside London, where he lives with his family, about his impactful career. Answers have been edited for clarity.

What was your childhood like?

We were a generation born just after World War II. There was a spiritual fog—Britain was very gray, and people were anxious that World War III might happen. My parents were believers, in their own way, and I realize now, looking back, that my grandfather was nurturing me. He would sit me down and show me his collection of stamps from around the world, introducing me to the wonder of travel, and the wonder of images. I was always putting a frame around things with my fingers: Excluding everything outside the frame let me see the object inside for what it really is.

How did that early interest in images develop?

I always knew I would work with pictures. I was a music DJ, I did a bit of modeling and acting, then I was lucky to get a tax refund, which meant I could buy a camera. By chance, I also inherited darkroom equipment and just started taking pictures. I knew a lot of people in the music industry, so that was the next step. I went to them and they commissioned me to shoot gigs. It happened very organically. I’ve never studied photography. Everything I do is by intuition.

What was London like in the 1960s?

It was a really interesting time, quite spiritual. As the sixties progressed into a cultural revolution of peace and love, the fog began to clear. We’d seen the effects of war and wanted no part of it. We just wanted to be free, to escape the heaviness. That set me off on my own quest.

Around 1967, I was sharing a house with the legendary radio DJ John Peel. There were always people coming and going, and one day this guy—Artie Ripp, the head of Buddah Records—turned up, handed me a silver box full of lenses and cameras and said, “I don’t need this right now. You keep it and give it back to me later.” That’s when my work started seriously.

A few years ago, I did a retrospective show in Istanbul, which forced me to make sense of my journey from music photography to photographing the Islamic world. Back then, Bob Dylan and The Beatles were heroes, the poets and sages of the time. Photographing them was a way for me to see them one to one. When you put a lens on someone, you see them as they really are; you’re stripping away all extraneous details, and you’re just concentrating on this one person in front of you. Then I realized it’s the exact same process photographing the sages of Islam. They are teaching the culture in the same way musicians in the sixties were teaching us the culture. Spirituality is what links it together.

After a while, as I got more successful, I met Artie Ripp again and was able to thank him and give him his box of cameras back.

But then you turned away from popular culture. What happened?

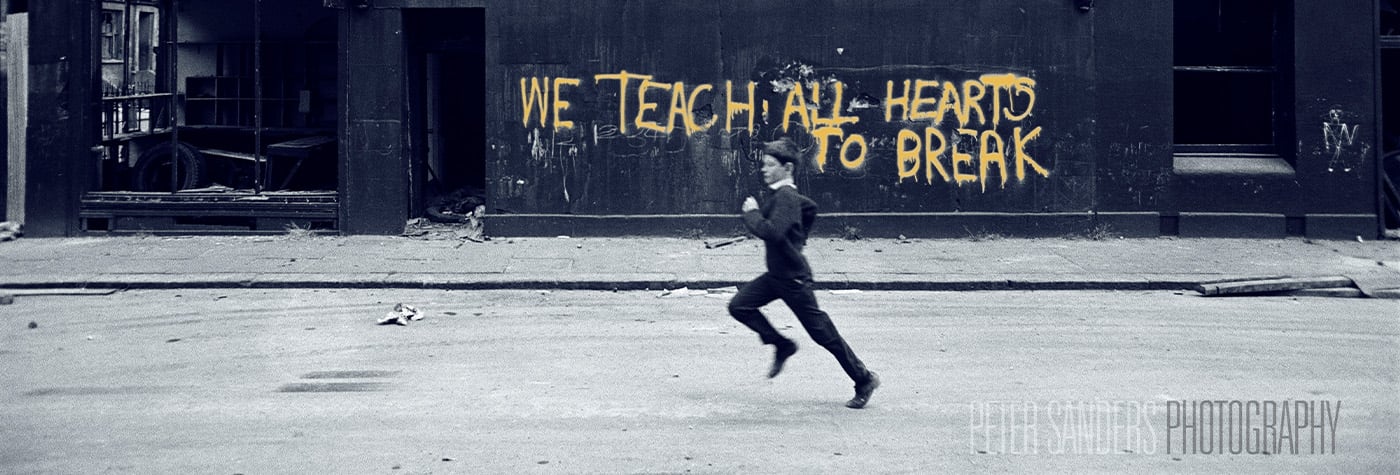

I can explain it through one of my pictures. In 1969, I discovered a street of derelict houses in London that had been painted black, where someone had graffitied “We Teach All Hearts to Break.” While I wondered what it meant, I lifted my camera and took the shot, just as a boy ran in front. From then, for the next two years, my life completely changed.

I started reading Emerson, and then I found Autobiography of a Yogi by Paramahansa Yogananda, an Indian spiritual master who brought meditation to America. Not long afterward, I photographed Jimi Hendrix a week or two before he died. Selling those pictures meant I could travel to India. I accepted Islam, I spent Ramadan in Morocco learning from Sheikh Muhammad ibn al-Habib, then I arrived in Makkah for the Hajj in January 1972.

Looking back, that slogan was a sign to me that I was going to go through some huge upheaval, that my heart was going to break open to accept bigger things. Sometimes you are shown signs and you don’t register the deeper meaning until later.

Now the world has changed, and everyone has a camera. Photography has become a universal language, like music was a universal language in the sixties.

Since then you’ve traveled widely and have been called the pre-eminent photographer of the Muslim world. What does that mean to you?

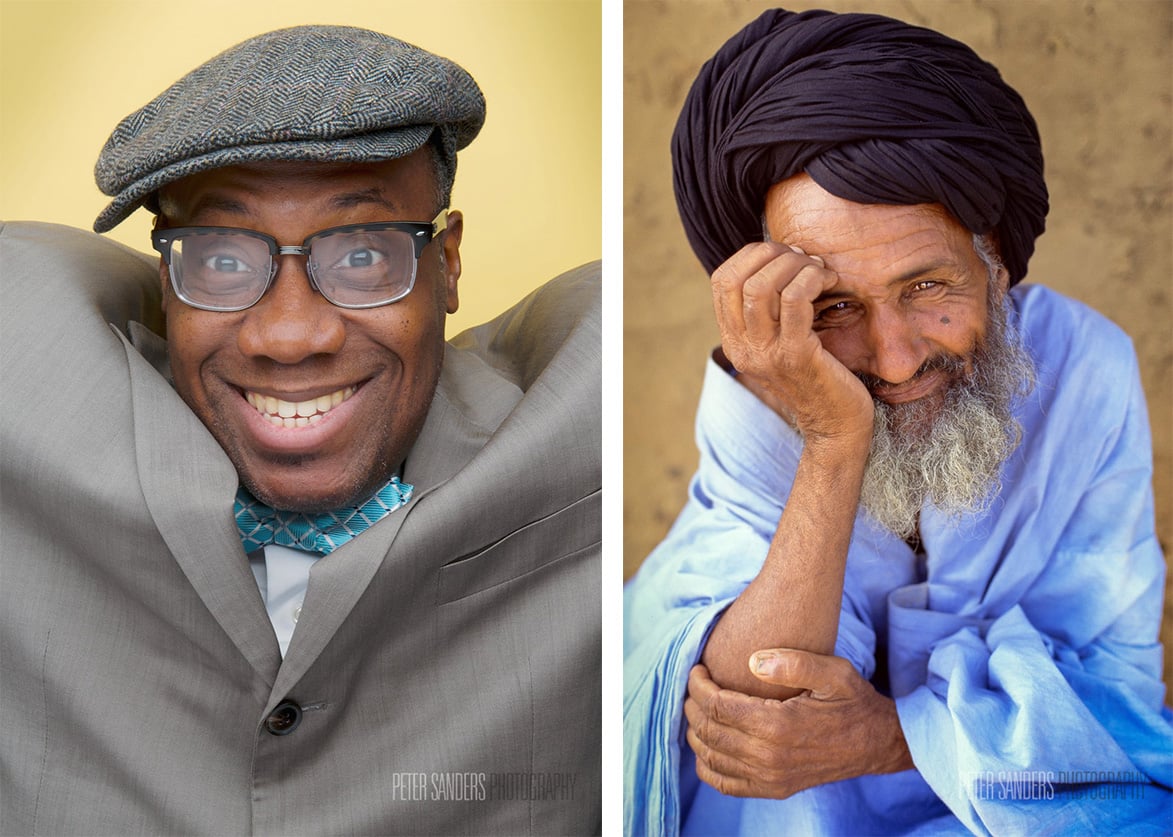

I always hoped I could be a bridge. In my early years, very little was known in the West about Muslims and Islam. I went to places that were not well known about—Mauritania, Sudan—wanting to find a pure, natural version of these traditional societies. It feels like God sent me around the world to capture pictures before the beauty vanished. Part of it was about seeking fusion. I remember being at the old mosque in Xi’an, China. The “moon gate” there has an inscription in Arabic—it’s a meeting of two worlds. Those worlds are so different, but there is fusion. That is so beautiful. It really inspires me.

My book The Art of Integration tried to do the same thing, showing ordinary Muslim people integrated into British society. That came out of respect, and respect for who’s in front of the lens is one way the great war photographer Don McCullin influenced me. I met him the first time in Iran, in 1979, and he’s taught me so much. I sent him Meetings With Mountains, my book about Muslim scholars and sages, which I’d been working on since Yogananda’s book planted the idea in my head that on a spiritual journey you need a teacher. Many of these people had never been photographed before, and Don’s first question to me when he saw it was, “Are you Muslim?” It’s so important in photography that the person needs to feel they can trust you. Don understood that and saw that trust in my pictures.

Who are some other influences?

[Henri] Cartier-Bresson was very important. Irving Penn, Platon, Jimmy Nelson. The great cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, with his philosophy of light and color influenced by Rembrandt.

But Roland Michaud was the sheikh of photography for me. He and his wife, Sabrina, both Muslims, photographed in Afghanistan before the wars. His work is so painterly. I love it. I met him not long before he died in 2020. We talked about his early realization that photography takes time. Every trip, they would spend months living very humbly with the people. One picture would take hours.

Islam definitely teaches about patience, taking your time. As a photographer, it also teaches you empathy, which I think is essential.

What do you think your legacy will be?

I have no idea! I’m waiting for someone to tell me. Meanwhile, I still feel I’m on a journey. I’ve spent decades as a loner, hiding behind my camera, trying to show people as authentically as I can. We live in a time when it’s all about selfies, but the spiritual people I’ve photographed don’t put on a second face for the camera. When they’re in front of you, there’s no ego. They are just themselves.

There’s a heron in my local park. He just sits quietly, observing everything. When anyone gets too close, he flies away. I really relate to him.

You may also be interested in...

In The Marshes Of Iraq

History

Arts

Amidst "the stillness of a world that never knew an engine... he found at last a life he longed to know and share.

FirstLook - A blistering triumph for the back-street boys

Arts

Amid the roar of racers zooming toward the finish line in London during the 1980 Grand Prix, longtime auto-racing photographer and renowned artist Michael Turner trained his lens on a Saudia-Williams FW 07.

FirstLook: Zillij in Fez

Arts

In patterns and refractions, the old city of Fez, Morocco, comes to life through the geometric tile works known as zillij. In 2001, AramcoWorld commissioned photographer Peter Sanders to tell the story of a family who for five generations has added new dimensions to art and architecture.