Latino Muslims - Reclaiming a New World

- Arts

- Migrations

12

Written and photographed by Joe Center

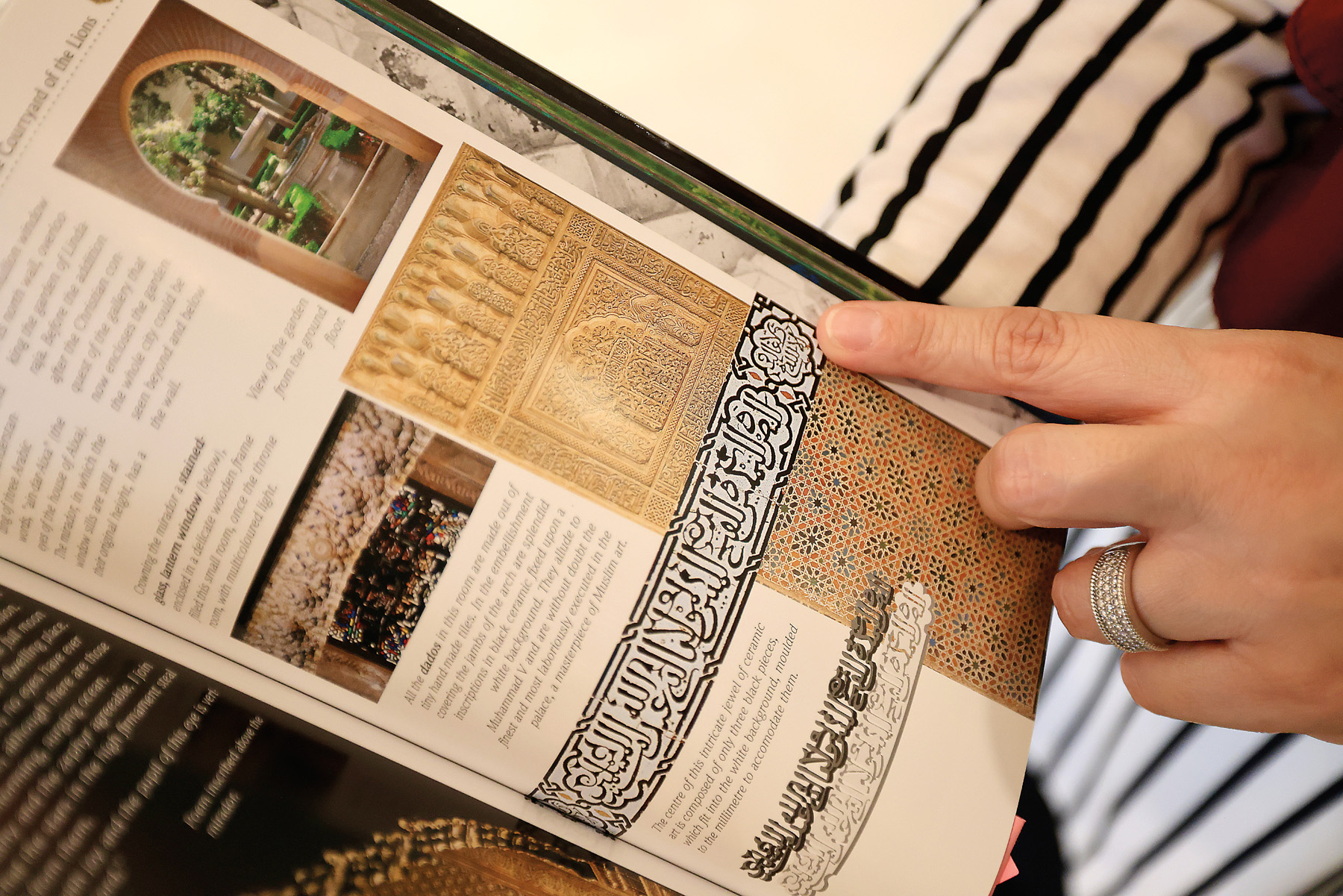

Elements from the mosque will be incorporated in the prayer room’s design.

When ‘Abd al-Rahman built the Great Mosque of Córdoba in what is modern-day Spain around 785 CE, he could never have known its distinctive red-and-white, two-tiered arches would reach from al-Andalus across an ocean.

The arches spanned the columns and capitals borrowed from earlier Roman and Visigoth stonemasons, but their broader architectural influence would stretch across the Atlantic to a continent yet unknown to the Muslim world. They bridged centuries, the ebb and flow of dynasties, cultural identities and languages, and a wholesale change in how the world communicated.

‘Abd al-Rahman’s arches today extend to a home for Latino Muslims in Texas, where they appear in an entry hall that leads to a prayer room oriented toward Makkah as well as an audio-visual production space.

“We envisioned building a place where all people are welcomed, a sort of mosque for non-Muslims. We live knowing our lives are Islam on display,” says Sandy “Sakinah” Gutierrez, a Colombian American Muslim. She is the co-founder of IslamInSpanish and the designing mind that brought the arches to Houston.

Her family is part of a distinct minority in the US. Latinos make up approximately 20% of the population, according to the US Census. As Colombians, Gutierrez says, they are a minority among Latinos (4%). As Muslims they are yet again a minority in the US. And while their numbers are growing, Latinos are a minority within Islam.

“We are four times minorities,” says Jaime “Mujahid” Fletcher, Gutierrez’s husband, also Colombian American. He is co-founder and media executive producer of IslamInSpanish. “We know what it means to be the ‘new kid,’ so we think about how we can make the first experience inviting and comfortable for people, so everyone knows they are valued here.”

Members of the diverse community at IslamInSpanish celebrate <em>Eid</em>. The space was decorated with mylar balloons spelling “Happy Eid” in Spanish.

According to Pew Research Center, the percentage of Muslim Americans identifying as Latino increased from 6% to 8% in the years between 2011 and 2017, suggesting perhaps the fastest growth segment in the American Muslim community.

But it hasn’t always been easy.

Alex Gutierrez, director of program development for IslamInSpanish, wears a ball cap that reads “Los Astros,” a reference to Houston’s beloved champion baseball team. “When I converted there was some pushback from family and friends. Finally, they had to see I’m still me. I’m still Houstonian. I’m still Latino. I’m still Colombian. We simply have different ways that we understand God.”

While firm numbers of Latino Muslims are somewhat elusive, what is clear is the dynamic interaction of Arab and Latino cultures. And this is nothing new.

Lofti Sayahi, professor of Spanish linguistics in the Department of Languages, Literatures & Cultures at the University of Albany, explains a major point of connection for Spanish and Arabic:

“The Muslim presence in the Iberian Peninsula that started in 711 CE lasted about eight centuries, during which there was a significant amount of bilingualism and language contact. Arabic was introduced as a dominant and prestigious language, which led to its adoption by peoples of different ethnic and religious backgrounds. This led, for example, to the emergence of a linguistic variety known as Mozarabic, from the Arabic word must‘arib, that was used by the Christians who remained in territories that were under Muslim control.

“If we count derivations and toponyms, there are about 4,000 loanwords from Arabic in Spanish, mostly having to do with culture, administration and agriculture.”

According to Craig Considine, a sociology professor at Houston’s Rice University, “Multiculturalism thrived on the peninsula during the al-Andalus period, with Muslim administrations promoting religious, cultural and academic freedom. Followers of Islam, Christianity and Judaism lived as their conscience and traditions dictated, and the tolerant, cooperative environment led to a golden era of science and medicine.

“Muslim scholars believed it is not enough to talk to one another. We must allow the cross-pollination of ideas to lead to new fruit,” says Considine, author of The Humanity of Muhammad: A Christian View. “Not merely tolerant, they embraced the diversity and knowledge, regardless of where it came from. It was about moving society forward.”

“Muslim scholars believed … we must allow the cross-pollination of ideas to lead to new fruit.”

— Craig Considine

Craig Considine

Speaking of Spanish expansion into the Americas after the Reconquista in 1492, he says:

“In many ways, the knowledge that the Spanish had seized or adapted—geography, astronomy, sailing seas—was Arab in nature. Muslim scholars had been working in these areas for centuries. Much of European exploration would not have been possible without Muslim scholars cultivating science.”

After 600 years of exploration and conquest, revolt and independence, the world now has “Latin America,” almost entirely speaking Spanish and Portuguese—from the two countries formed from al-Andalus. Their conversations are peppered with Arabic, their food, sweetened with azucar.

“Sugar” in English is azucar in Spanish, from the Arabic sukkar. And sugar cane is a major Colombian export crop.

For Latino Muslims Eid celebrations include taking turns hitting a piñata while blindfolded until its candy spills out for children.

Jaime “Abu Mujahid” Fletcher, father of the younger Jaime, is a retired agricultural engineer, having worked with sugar-cane plantations for much of his career in his native Colombia. Today he lives in the US and is the voice for many audio productions of Islamic material in Spanish, including a recitation of the entire Qur’an.

“People would meet me and say they recognized my voice. It had to be from recordings because this was before social media was a big thing.”

The voice is a low baritone, smooth and mellowed by eight decades. He talks about there being an order between the sky and the earth, growing orchids and all things to do with agriculture. “You can’t have Spanish rice without rice. And it was Muslim agriculture that made rice farming possible on a large scale in Spain. That was a thousand years ago.”

Arab settlers in Spain introduced other food crops: artichokes, almonds and figs, date palms, citrus trees and bananas, all important elements of Latin American cuisine today.

A snapshot of cross-cultural pollination could be found on the iftar table at a public park in Sugar Land, Texas. The potluck meal came together as members of the IslamInSpanish community brought food from each of their own traditions or personal preferences, all halal, or prepared by Islamic standards. Turkey shawarma sat next to pasta salad and fried chicken, figs and sliced fruit. Baklava competed with pink-frosted doughnuts with bright sprinkles. There was Colombian coffee along with other nonalcoholic drinks.

The community was a cross section of Latin America, with attendees hailing from Central and South America, Mexico, the Caribbean and the United States. But the gathering drew from far beyond the Western Hemisphere: All of the world’s continents were represented, except Antarctica.

Eveliz Gutierrez, left, supervises as her niece Jaliliah Fletcher works the dough to make buñuelos, traditional Colombian fried pastry balls, at a family gathering.

Alex and Eveliz Gutierrez, joined by their daughter, show off their homeland pride via their bilingual IslamInSpanish shirts.

A welcoming spirit spills over into all the activities of this community. And here the greatest cross-cultural connection between the Arab world and the Latino Muslim becomes undeniably apparent: hospitality. The culture developed over centuries of living in a harsh environment—welcoming the stranger, feeding the hungry, giving the traveler rest—finds a fresh manifestation among the minority within a minority.

Considine invites IslamInSpanish to speak with his class at Rice University each year. “These folks are cultural navigators. They can make the ‘foreign’ seem ‘familiar’ and help students learn to look with fresh eyes. For myself, when I began studying what Islam is really all about, I noticed similarities between my faith and Islam. Islam made me a better Roman Catholic. I became better by seeing the way they lived in community, with generosity and kindness.”

Dinner at the Fletcher home puts that generosity and kindness on display. Latina women wearing hijab prepare traditional Colombian food, the halal way. The family atmosphere and the aroma of rice, beans, roasted chicken, fried plantains and yucca are as inviting as the hosts themselves. And buñuelos, the traditional fried pastry balls, add the meal’s exclamation point.

IslamInSpanish’s Alex Gutierrez, left, director of program development, and Jaime “Mujahid” Fletcher, cofounder, prepare to record a Ramadan message.

It is like many Eid celebrations around the world, except this one has a piñata—a classic must-have for a Latino celebration with children—and the sermon is in Arabic, English and Spanish, and is delivered by a first-generation American and convert.

Isa Parada was born in New York after his family emigrated from El Salvador; then they headed to Houston. After converting, he attended the Islamic University of Madinah, and today he serves as imam, educational director and spiritual counselor at IslamInSpanish. Addressing the community on the morning of Eid, he asks those gathered to consider a world in need, regardless of languages spoken or foods served.

Or clothes worn, for that matter.

While people may convert when they believe they have found a “perfect fit” in Islam, Jaime “Mujahid” Fletcher says, that doesn’t erase previous expressions of cultural identity.

“It made me a better man. It didn’t change my clothes,” says Fletcher, who typically wears a polo-style shirt and khaki pants. “I don’t dress like I’m from Saudi [Arabia] or Indonesia or Nigeria—that would be cultural appropriation. The clothes that I wear are Muslim dress. Because I’m Muslim.”

Jaime “Abu Mujahid” and Heddy “Umm Mujahid” Fletcher are still sweet on each other, as their sugar bowl suggests.

Alex Gutierrez agrees but on an even broader scale. “There are many subculture Muslim groups, like South Asian or African or Arabs, and everybody has their own way of living into it,” he says. “As new Muslims, we studied from historical sources to help us establish what is culture and what is Islam. We value any opportunity to fix misconceptions, so it’s a great blessing to be able to be kind of a cultural bridge.”

The co-founders of IslamInSpanish see themselves as blessed to have found Islam. Jaime says: “My life was very troubled before becoming Muslim. Gangs, violence. It wasn’t good. Now I know what it means to have a high-level, universal product. And to really value it because I found it when I had nothing.

“Our task now is to make sure our daughters always cherish what they have. They were born into Islam. They didn’t have to find it. But even though it is their birthright, so too is their history, where they came from. And they will always honor and value both, never take them for granted.”

You may also be interested in...

A Land and a Camera: The Legend of Sami Kafati

Arts

By tackling often overlooked societal issues, Palestinian-born Sami Kafati’s body of work has shaped Honduran cinema even years after his passing.

Creating Harmony Through Tradition in Japan

Arts

In the Yoyogi district of Tokyo, Japan, stands the ornate Camii Mosque, in a location where there is a blend of cultures—educating locals and creating a harmony among traditions. Islam’s history in Japan is almost entirely recent, with estimates putting the number of Muslims in Japan close to 200,000 amid a national population of 125 million. “The point is to help people acquire the power of interpretation, the intellectual muscles of critical thinking and critical understanding of this world,” says Qayyim Naoki Yamamoto, professor of Islamic studies at Marmara University.