Camels and Culture—A Celebration

- Arts

- Science & Nature

Written by Shaistha Khan

Photographed by Hatim Oweida

Video by Holam Entertainment

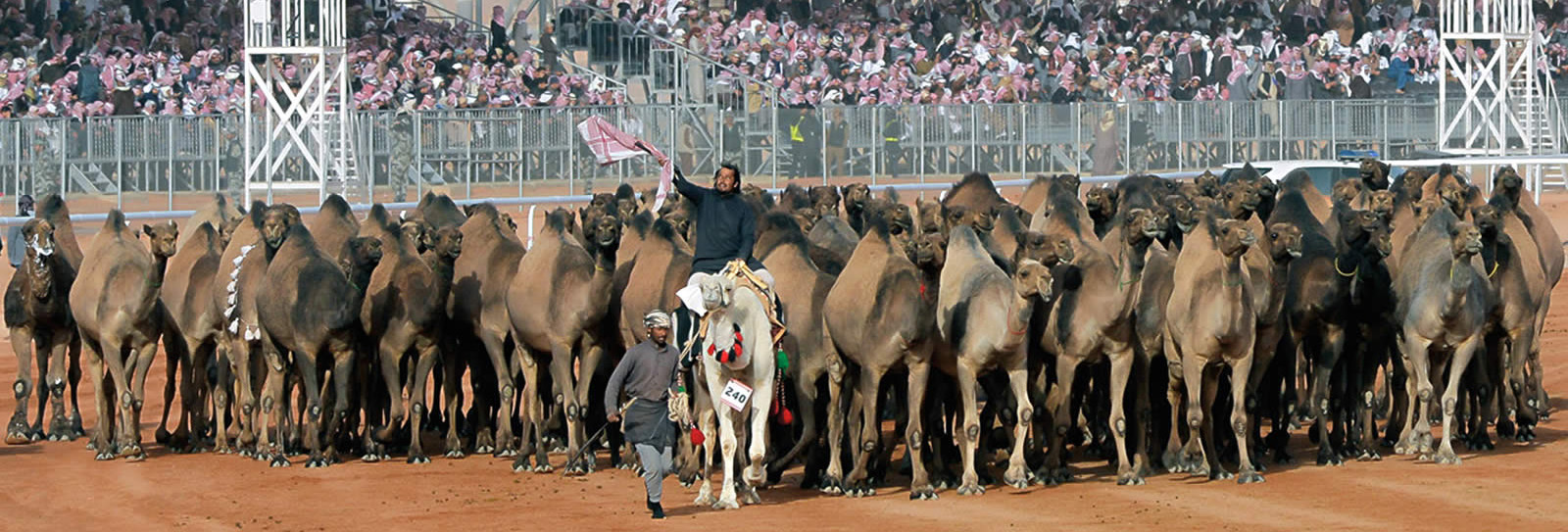

As the morning mist dissipates over the flat desert, a rider mounted on a camel bedecked with red tassels calls out and, as one, 100 camels break into a trot at the end of a long straight track. These are purebred sheqah camels, beige in color and native to ‘Ar’ar, near the northern borders of Saudi Arabia. Spectators in the stands cheer as the camels flow by, humps a-bobbing and knees a-jutting; a couple of drones whir overhead. A few hundred meters down the track, the driver beckons a second time. Barely breaking its motion, the herd turns and parades back to its starting point.

It’s the 100-camel herd competition day at the Mazayen al-ibl, the Camel Beauty Contest, which also features 10-, 20-, 30- and 50-camel events, dozens of individual competitions and an entire, separate, eight-kilometer circuit and viewing stands devoted to camel racing. What started more than two decades ago as a Bedouin festival in northern Saudi Arabia has become, over the past two years, the King Abdulaziz Camel Festival, an officially sanctioned, 28-day celebration of the national animal. This year it has drawn more than 300,000 spectators, and 1,900 owners have brought with them the main attractions: 38,000 camels.

Headed by the Riyadh-based King Abdulaziz Foundation for Research and Archives, the festival offers more than a dozen events and pavilions for exhibitions, history, crafts and more, all amid newly built, permanent fairgrounds. It’s aimed at attracting urbanites—who these days may be no more familiar with camels than their peers in Texas might be with horses.

“There is a big audience for camel-related activities,” says Fawaz al-Muhrej, a board member of the government’s newly established Camel Club, which is charged with promoting camel-related events nationwide. Last year, he explains, camel events in Saudi Arabia were “consolidated and aligned” with the kingdom’s Vision 2030, the national strategy for economic diversification.

“The festival aims to evolve into a global event, with pavilions and camels from other countries,” al-Muhrej adds, “a world-class, international affair, one that people will automatically associate with Saudi Arabia.”

Now situated just outside the city of Rumhiya, northeast of Riyadh, the festival occupies more than 10 square kilometers with dedicated areas for the beauty contest, and races; as well as auctions, markets and a central area for family entertainment showing rare camels, camel-hair art, a photography contest and cultural exhibits. As al-Muhrej explains, this is intended to be just the start of much more: Plans include camel safaris, camel-

milk factories, camel hospitals and camel-research centers.

Listening to al-Muhrej, I can’t help but wonder why, in the 21st century, put on such a traditional event? Why not something ultramodern and international, like a Grand Prix Formula 1?

Sultan al-Omani has been judging camels for well over 30 years, both in Saudi Arabia and in the United Arab Emirates (uae). Watching the sheqah herd, he scribbles a few numbers on a piece of paper, perhaps crossing out a previous rank-holder. Beauty here lies in the eyes of highly trained beholders: the judges. The height of the she-camel; the shape of its nose and lips; its body structure and proportion all count: “Nothing is bigger than the rest,” al-Omani explains.

“Her body should not be too fluffy and fat, nor too skinny. The hump to the back is well rounded. There is a proportional distance between the hump and the neck. The neck should be long and thin. The nose should be long and a little wide at the bridge—this is a very good sign of beauty. The ears are pert, and lips should droop. The taller the camel, the more beautiful.”

Nearby, Abdulaziz al-Musa, 18, is at the festival to present his father’s camels at the beauty contest. He’s grown up attending camel festivals, and last year, the al-Musas won a second-place prize that paid $200,000.

To breed and grow beautiful camels, he explains, the al-Musas feed their camels a diet of barley and dry hay. The herd has an exercise regimen that includes long rounds twice daily and veterinary checkups monthly. “I think it will be a tough competition between the amir’s [prince’s] camels and our camels,” he jokes.

With a total of $57 million in prize money to be handed out by the end of the festival, and some $31.8 million of that for the beauty contest alone, stringent rules are in place to ensure fair play. Electronic registration sees every camel fitted with a microchip that stores details of the camel and its owner, and camels are inspected before each event. With such rich bounty, and social prestige in owning what could be literally a million-dollar beauty or herd, the stakes are high—and emotions run strong.

Despite these incentives, though, Jasser al-Hajri agrees they are nostalgic for the simpler, at times even chaotic, old Mazayen al-ibl. They say, that was a more social gathering where camel breeding and herding families come together to appreciate beauty and finesse. “Now, everyone wants to be the best and win,” says al-Hajri.

This year there are indeed more ways to win: For the first time, there is a camel obedience contest. Fawzan al-Madi, head of the Organizing and Field Committees, has championed the new contest.

“There are several ways to test the obedience of camels: simple tests like having the owner command it to sit or stand up, or the handler serve the camel some food, and if it continues eating despite the handler calling, the camel is deemed undutiful,” says al-Madi.

More complex tests involve making two differently colored herds walk into each other. “If one camel follows the wrong herd to the other side, the herd loses. The handler will also take the camels through very tight spaces, causing some of them to get scared and back away,” he adds. At the heart of the competition is the assurance that the owner and his camels remain inseparable.

Farther away from the fairgrounds, at the camel auction, men and boys gather around a pen as the auctioneer, megaphone in hand, enters and invites bids on a golden-yellow she-camel and her calf. “What? No takers?” he asks, tossing out a stream of friendly banter and cajoling. He presses on, the rising pitch of his voice suggesting that this duo is a prized pair that will be worth a lot more than what meets the eye. One observer speculates the price might go up to $60,000.

Some 400 transactions have taken place during the first three weeks of the festival, and this has led to a nationwide increase in camel prices, says Fahad Saeed al-Diryabi, owner of the auction house. Here, he explains, buyers can take home anything from an individual camel to a whole herd. Camels can cost as much—or more—than luxury cars, pickup trucks and desert-popular 4x4s: from about $1,500 for the most ordinary dromedary all the way to more than $750,000 for a top, breeding-ready beauty or racer. People buy for all kinds of reasons too, he adds. “A camel calf will make for grand banquet dinner, a male camel for racing or procreation, or a beautiful she-camel to grow their herd and take part in future competitions.”

The most sought-after camel breeds are the yellow she‘al, the white widhah and the suffur, which are yellow with dark humps. Al-Diryabi proudly recounts a tale of a purebred camel he sold that went on to win at the races for three years in a row.

At the end of my two-day visit to the festival, speaking with camel enthusiasts, experts, contenders and others, I find an answer to the question I came with. As I watch them lovingly pet and play with their camels, ardently recite camel poetry and narrate camel tales, I am reminded how much the humble dromedary is integral to the identity of this country. It was on camels that the earliest traders helped build this region’s first civilizations, and it was on a camel that in the early 20th century King Abdulaziz Al Sa‘ud united today’s kingdom. Riding on such legacies, the festival reinforces a sense of pride more than any Grand Prix ever could.

About the Author

Hatim Oweida

Photojournalist Hatim Oweida is also based in Dhahran, where he works as a staff photographer with Saudi Aramco’s Media Production team.

Shaistha Khan

Shaistha Khan is a public relations and freelance writer based in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. She writes on travel, food, culture and topics that resonate with multicultural millennials like herself.

You may also be interested in...

A Reimagined Islamic Garden

Arts

The second Islamic Arts Biennale (Jan 24-May 25, 2025) in Jeddah explores multicultural expressions of faith, healing, regeneration and an appreciation of beauty.

Revival Looms

Arts

In Georgia Borchalo rugs are making a tentative comeback amid growing recognition of the uniqueness of ethnic Azerbaijani weaving. There’s hope that this tradition can be saved.

A Fasting Journey Through Ramadan

Arts

What’s it like as a non-Muslim to fast during Ramadan? Writer Scott Baldauf shares his journey through the holy month where he uncovers resilience, empathy and the powerful unity found in shared traditions.