Historian William Dalrymple titled his 1998 review of The Travels of Dean Mahomet: An Eighteenth-Century Journey through India, “An Indian with a Triple First.” It was an apt choice: The Travels was the first book ever published by an Indian writer in English, and the author was also the founder of London’s first Indian restaurant. To complete his hat trick, Mahomed—the spelling he used later in life—made a lasting name for himself in the English seaside resort of Brighton by bathing the royal, rich and famous.

Mahomed’s Travels would have remained confined to the rare-book sections of the few great libraries that hold an original copy if it were not for Michael H. Fisher, a professor of history at Oberlin College in Ohio. He persuaded the University of California Press and Oxford India Press to republish Mahomed’s memoir in 1996 complete with his own biographical sketch of Mahomed.

Last spring I spent a week in London and Brighton tracing the footsteps of Dean Mahomed, which is an Anglicized version of his given name, Din Muhammad. I sought out first Rozina Visram, whose 1986 book Ayahs, Lascars and Princes: The Story of Indians in Britain 1700–1947 discovered Sake Dean Mahomed for our contemporary era. We met at the British Library. My first question to her was why she had featured Mahomed in her book. Her answer: “I wanted to rescue him from obscurity.” She explained it was she who had inspired Fisher to republish Travels.

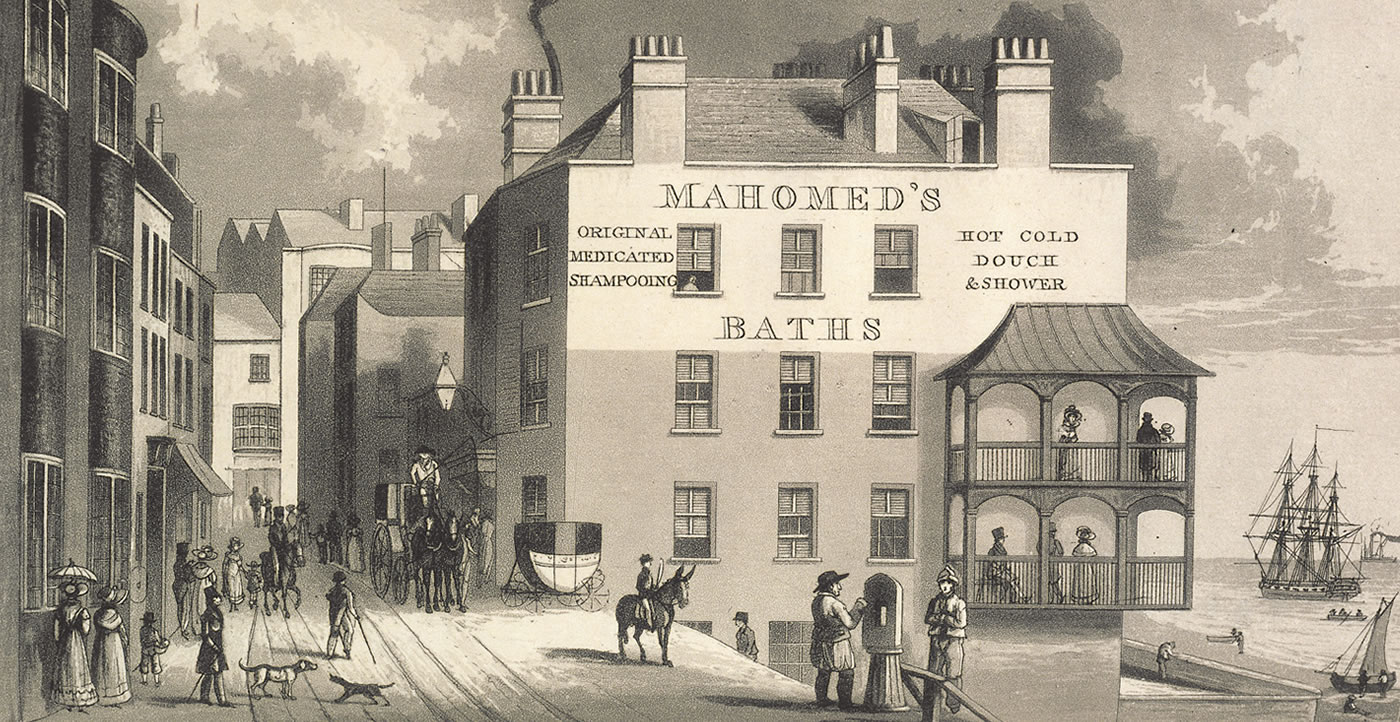

The next day I took a 57-minute train ride to Brighton. Within minutes of arrival, to my great surprise, I spotted, on the side of a number 822 city bus, the name “Sake Dean Mahomed.” (He adopted “Sake” as an Anglicization of shaykh in the 1820s.) I soon learned this bus sign was part of a civic campaign to honor notable citizens, and that there are today more traces of Mahomed in Brighton than one might expect. A formal portrait of Mahomed, attired as a Georgian gentleman, hangs in the Brighton Museum, painted by English artist Thomas Mann Baynes. Along the sea, the Queen’s Hotel stands on the site that was once Mahomed’s Baths. At 32 Grand Parade is the house where he died, aged 92.

Dean Mahomed was born in 1759 in Patna, today the capital of India’s eastern state of Bihar, about 600 kilometers from Kolkata. According to Mahomed’s autobiographical sketch, his father was a subedar, a military rank roughly equal to lieutenant, the second highest permitted to Indians under British colonial rule. He served in a battalion of sepoys (Indian and Bengali soldiers) in the Bengal Army of the East India Company. Mahomed was 11 when his father was killed in battle.

Some years later he took service under an Anglo-Irish officer named Captain Godfrey Baker and, like his father, rose through the ranks. In 1782 Captain Baker decided to return to Ireland, and he invited Mahomed to accompany him. “Convinced that I should suffer much uneasiness of mind, in the absence of my best friend,” Mahomed resigned his commission and left India—never to return. Twenty-five years old, Mahomed settled in 1784 in the small Irish port city of Cork, where he worked for the Baker family on their estate for the next 22 years.

He also went to school to master English, which he did successfully enough, because it was from Cork in 1794 that he published his historic two-volume Travels. His work, says Fisher, shows an “elegant command over the high English literary conventions of the day.” To market the book, Mahomed took out a series of newspaper advertisements, and he published Travels by subscription, as was common at the time. “Testifying to his acceptance as a literary figure,” says Fisher, “a total of 320 people entrusted him with a deposit … long in advance of the book’s delivery.”

In 1806, at age 47, Mahomed moved to London and married again. He headed for fashionable Portman Square, home and haunt to former East India Company employees referred to—pejoratively, at times—as nabobs, an Anglicization of the Mughal title nawab. He found employment with the richest nabob of them all, Sir Basil Cochrane, who had made a fortune in India on supply contracts with the British Navy. Cochrane had published several tracts promoting the use of “vapor” (steam) baths to relieve medical complaints, and he had even installed one at his home. Mahomed is believed to have added an Indian treatment of therapeutic massage to Cochrane’s vapor treatment, thus creating the salubrious formula that later was to become the sensation in Brighton.

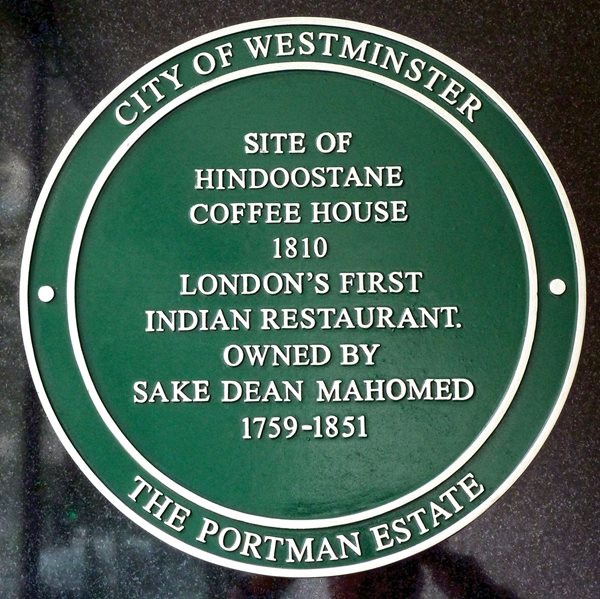

In 1810, around the corner from Portman Square at 34 George Street, Mahomed opened London’s first Indian restaurant, called the Hindoostane Coffee House. The Epicure’s Almanack—London’s first restaurant guide—described it as a place “for the Nobility and Gentry where they might enjoy the Hookha with real Chilm tobacco and Indian dishes of the highest perfection.… All the dishes were dressed with curry powder, rice, cayenne and the best spices.” Despite the raves, Mahomed was unable make it a success. He declared bankruptcy two years later.

![In Ireland Mahomed perfected his English, and in 1794 his two-volume <i>Travels</i> became the first book in English by an Indian-born author. In it he describes “champing”—shampooing—in which the client “lies, at full length, on a couch or sopha [sic], on which the operator chafes or rubs his limbs, and cracks the joints of the wrist and fingers.”](https://prodcms.aramcoworld.com/-/media/aramco-world/articles/2018/the-shampooing-surgeon-of-brighton-images/image-4.jpg)

At the age of 55, Mahomed moved to Brighton. It was 1814, the year after the publication of Jane Austen’s most popular book, Pride and Prejudice, in which 15-year-old Lydia is consumed by a youthful infatuation with fast-growing, fashionable Brighton—sentiments that could offer a man like Mahomed an opportunity for a new start:

In Lydia’s imagination, a visit to Brighton comprised every possibility of human happiness. She saw, with the creative eye of fancy, the streets of that gay bathing-place.

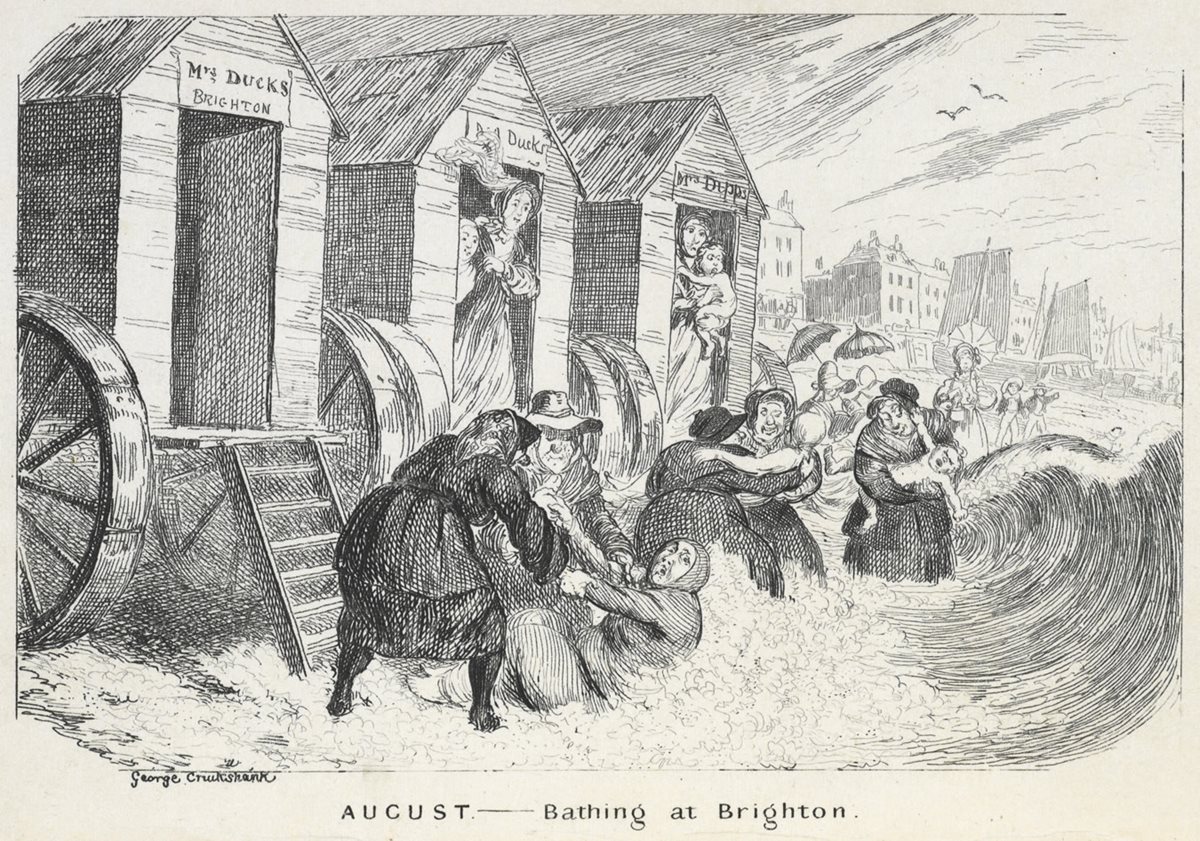

Brighton’s fame as a health resort began in the 1750s with the dissertation by Richard Russell, M.D., asserting the curative benefits of seawater. There was, however, one problem: Most people couldn’t swim. This led to the development of a bathing apparatus: a small wooden room, fitted with carriage wheels, drawn into the sea by horse. After having disrobed the bather, a professional “dipper” would dunk the patient in the sea one or more times, depending on wave conditions, weather and the client’s fitness. Once the “cure” was complete, the client changed back into street clothes and the horse made the return ashore.

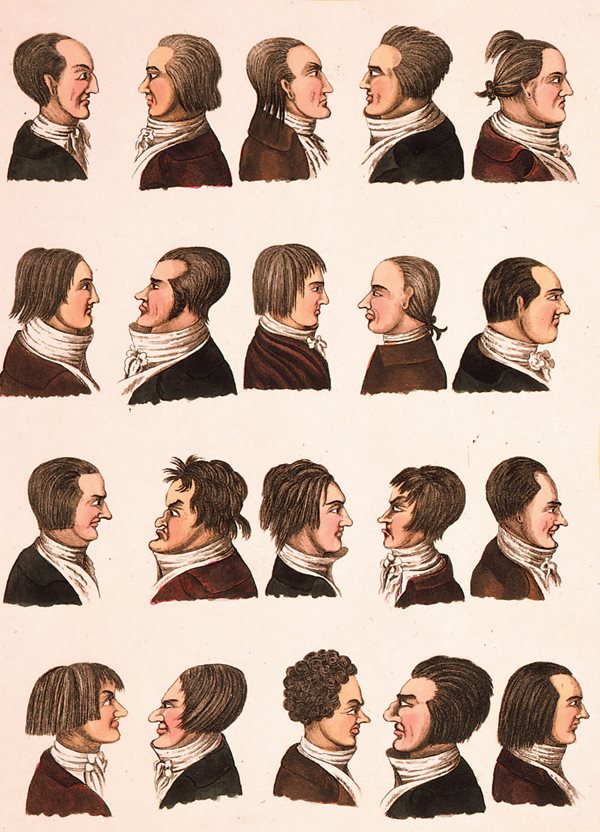

Mahomed offered a far more convenient, private and certainly less chilly “cure.” First came a kind of early form of aromatherapy: The client lay in a heated aromatic vapor or steam bath infused with Indian oils and herbs. After the client started perspiring freely, he or she was then placed inside a kind of flannel tent with sleeves protruding inwards that would allow the operator, from outside the tent, to massage the bather vigorously.

Mahomed described this process using the Hindi word chámpná, to knead or vigorously massage, eventually adopting an Anglicized version of it and billing himself as a “shampooing surgeon.” (Only later did “shampoo” come to mean hair-washing and hair soap.) It was around this time Mahomed added the title “Sake” to his name.

Former Royal Pavilion Director Clifford Musgrave wrote in his 1970 Life in Brighton:

The fashionable invalids were eager for some fresh way of whiling away their time, and the highly scented steam baths were found by many to be far more agreeable than sea-water baths, whether hot or cold, and to sufferers from rheumatism and kindred ailments the massage was soothing and relaxing. There was, moreover, the intriguing sensation that one was enjoying something of the voluptuous indulgences of the East.

In 1820 Mahomed’s opulent, bathhouse opened on the Brighton seafront. Visitors entered through a splendid vestibule where graphic testimonials were kept in the form of abandoned crutches, spine-stretchers, leg-irons, club-foot reformers and other paraphernalia from patients Mahomed had cured. The clientele amused themselves in reading rooms beautifully painted with Indian landscapes before moving to private marble baths. (Unseen by patients in the basement was the technology that pumped all seawater and freshwater the bathhouse required: a steam engine.)

Word spread, and quickly a visit to Mahomed’s Baths was de rigueur for English ladies and gentlemen as well as commoners plagued by gout, rheumatism and other maladies. Prominent figures such as Lord Castlereagh, Lord Canning, Lady Cornwallis and Sir Robert Peel frequented the establishment. So did the niece of the king of Poland, Princess Poniatowsky, who in gratitude presented Mahomed with an engraved silver cup that is now on display at the Brighton Museum. Mahomed became known simply as “Dr. Brighton.”

On my own first full day in Brighton, I went to see David Beevers, keeper of the Royal Pavilion. He explained that in another “amazing coincidence” the Royal Pavilion was being transformed by architect John Nash (designer of Buckingham Palace and much of Regency London) into a kind of Indian fantasia “just as Mahomed came to Brighton.” Nash’s client was none other than King George iv, who as prince regent had ruled for his father, George iii, during the latter’s terminal illness. “Shampooing surgeon” became a title of royal appointment. In 1825 Mahomed installed a private royal vapor bath next to the king’s bedroom in the Royal Pavilion, which Musgrave described as “a large marble plunge bath, with pulleys attached to the ceiling by means of which the Royal person could be lowered into the waters in a chair.”

Added Beevers:

When Mahomed came to the Royal Pavilion to “shampoo” the king, he wore an official costume modeled on Mughal imperial court dress now on display in the Royal Pavilion. But he would have put on something more practical whilst the massaging process took place.… Mahomed did much business with the royal household. Besides baths and shampoos, which cost one guinea each, he sold it bathing gowns of twilled calico and swanskin flannel, and other bathing gear.

The royal vapor bath was dismantled in 1850, said Beevers, which was “a great pity,” though there are hopes it might be restored because “Mahomed was a remarkable person, and there is increasing interest about him.”

After the death of King George IV in 1830, his younger brother succeeded to the throne as King William IV. The new king was as fond of Brighton—and shampooing—as his brother had been, and he kept Mahomed on as “shampooing surgeon.”

By the mid-1840s, when Charles Dickens was writing Dombey and Son, “shampooing” was sufficiently well-known to the reading public that he was able to write of his fictional character Miss Panky that she was “a mild little blue-eyed morsel of a child—who was shampooed every morning, and seemed in danger of being rubbed away altogether.”

James Smith, a frequent contributor to London literary reviews at the time, composed a poetic tribute he called

“Ode to Mahomed, The Brighton Shampooing Surgeon”:

O thou dark sage, whose vapour bath

Makes muscular as his of Gath,

Limbs erst relax’d and limber:

Whose herbs, like those of Jason’s mate,

The wither’d leg of seventy-eight

Convert to stout knee timber:

The ode continued, attributing Brighton’s growth to Mahomed’s fame:

While thus beneath thy flannel shades,

Fat dowagers and wrinkled maids

Re-bloom in adolescence,

I marvel not that friends tell friends

And Brighton every day extends

Its circuses and crescents.

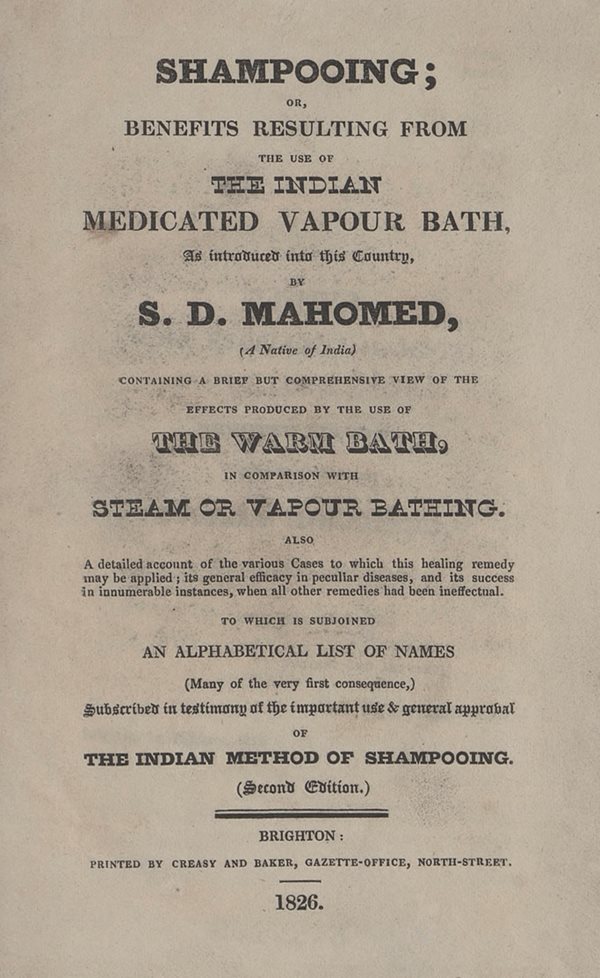

First published in The New London Magazine in 1822, these verses later appeared in Mahomed’s own self-promoting collection of testimonials. Originally titled Cases Cured by Sake Dean Mahomed, a second edition with the much longer title, Shampooing; or, Benefits Resulting from the Use of The Indian Medicated Bath, as Introduced into this Country, followed a few years later in 1826, with a third edition in 1838.

Of course, not everyone sang the praises of shampooing. Charles Molloy Westmacott, a British journalist and author who wrote humor and satire under the pseudonym Bernard Blackmantle and served as editor of The Age, the leading Sunday newspaper of the early 1830s, claimed that although shampooing “is in great repute [in Brighton],” it is “a sort of stewing alive by steam, sweetened by being forced through odoriferous herbs … dabbed all the while with pads of flannel.”

Mahomed shared his success, and he became a donor to local charities and the official steward for the Annual Charity Ball. He played a prominent role in the life of Brighton, illuminating the baths with gaslights to celebrate royal arrivals and anniversaries. “Mahomed was a generous and kind-hearted man,” says Visram, “always willing to help the poor and needy, either by giving them free treatment or by donations of money.”

Queen Victoria, after her accession to the throne in 1837, also made several visits to Brighton but, as Musgrave makes clear, quickly found the Pavilion not to her liking.

The lack of privacy at the Pavilion … made the place quite unsuitable for a couple who demanded the complete separation of their private family life from their State existence.… Writing to her aunt, the Duchess of Gloucester, from the Pavilion in February 1845, the Queen complained “the people are very indiscreet and troublesome here really, which makes this place quite a prison.” … Punch published an account entitled “The New Royal Hunt,” which protested fiercely against the fact … that “Her Majesty and her Royal Consort cannot walk abroad, like other people, without having a pack of ill-bred dogs at their heels, hunting them to the very gates of the Pavilion.”

As the pavilion lost its special standing as a royal residence, so Mahomed lost his royal patron.

Mahomed died in February 1851 at his son’s home, 32 Grand Parade, Brighton. According to Fisher, newspaper obituaries “uniformly took the tone that Dean Mahomed, once so important to the town’s development, had largely been forgotten.”

In his review, Dalrymple described Mahomed as “constantly charming and infinitely adaptable, intelligent and sharp-witted, part charlatan and part Renaissance man.” To which Visram added that “Mahomed may have been a self-publicist—and he had to be to succeed—but there is no doubt of his skill. The medical profession of the time was impressed.” In the end, Fisher asserted, “Mahomed negotiated for himself a distinguished place in British society.”

You may also be interested in...

America’s Arabian Superfood

Food

History

In recent years in the United States, dates have been trending as a nutrient-dense, easily transportable source of energy. Nearly 90 percent of US-grown dates are from California’s Coachella Valley. Yet the date palm trees from which they are harvested each year aren’t native; they were imported from the Arab world in the 1800s. Over the years, they have become a part of Coachella’s agricultural industry—and sprouted Arab-linked pop culture.

The Bridge of Meanings

History

Arts

There is no truer symbol of Mostar, Bosnia-Herzegovina, than its Old Bridge. The magnificent icon of Balkan Islamic architecture was destroyed during the 1992–’95 war—but not for long. Like the multicultural workforce that produced the original hundreds of years earlier, a broad team of architects, engineers and others came together immediately to plan its reconstruction. This summer marked the 20th anniversary of the bridge’s reopening.

Histories on a Plate-Reflections on Food and Migration

Food

History