Building Cultural Connections

- Arts

- Architecture

12

Written by J. Trevor Williams

Photographed by Ryan Huddle

After becoming a specialist in the architectural history of India in the 1960s, Attilio Petruccioli encountered a paradoxical problem.

The more the Italian architect learned about design sensibilities east of the Mediterranean and the confluence of cultures that led to their emergence, the fewer resources he realized existed to educate those in the West interested in Islamic architecture.

Captivated by its images, in 1968 he began collecting print issues of AramcoWorld and would continue for a quarter century, using them as teaching tools in classes as he became an established academic.

Before the magazine Mimar appeared in 1981, he says, AramcoWorld was the only international magazine with a sustained focus on architecture in the Middle East and the Islamic world.

“All that period, there was nothing. Of course, you could relate to archaeology, and there were books here and there, but essentially, it was the only magazine,” Petruccioli says.

But AramcoWorld did something else that esoteric publications did not; the magazine added human context to a discipline that often focused on the form of buildings with little regard for the people who used them, he says.

“I found interesting the idea of introducing interdisciplinarity for the first time, to my knowledge—the idea that architecture could be connected with cuisine and other aspects of life,” says Petruccioli, who went on to found his own magazine, Environmental Design, and study urban design and gardens in the Islamic world.

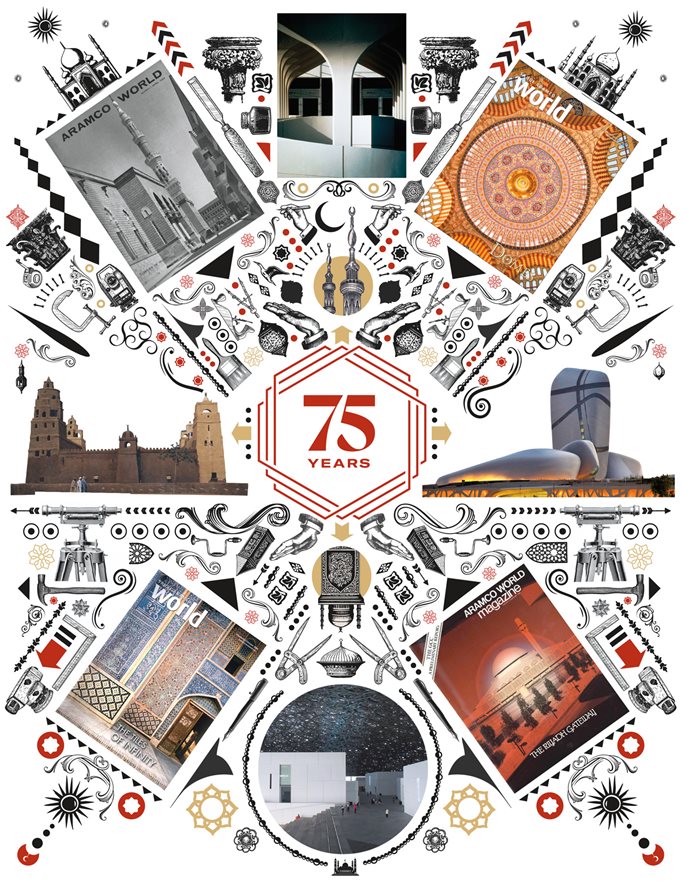

While AramcoWorld has never had a formal section devoted to architecture, since its beginnings 75 years ago the magazine’s editors have viewed the discipline as an essential lens on history and a crucible for cultural connections.

“Architecture is an excellent one for crossing both geography and time because so much of it endures, unlike, say, music or food recipes or even clothing designs, all of which do not survive centuries as well,” says Richard Doughty, a photojournalist and longtime AramcoWorld editor.

During his nearly 30-year tenure starting in the 1990s, Doughty tried to keep a sharp focus on the sciences and architecture, using them to tell stories of global interconnection.

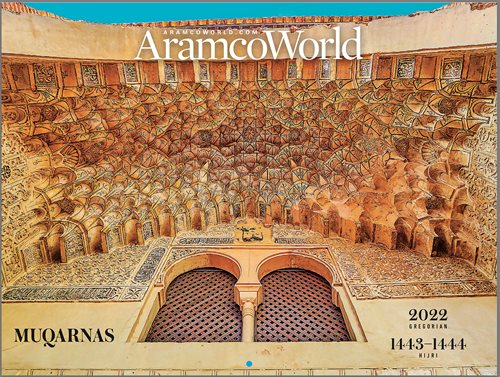

Sometimes those highlighted design elements in mosques and palaces, drawing out how stylistic elements and practical innovations shaped the arc of history. One of Doughty’s favorite motifs is the muqarnas, a three-dimensional, tessellated geometric pattern often found above doorways and in the negative space created in the corners of domes.

“It’s a metaphor for an infinite cosmos, and it’s also the most complex pattern mathematically,” says Doughty, who inspired AramcoWorld to produce a calendar featuring nothing but muqarnas. “It creates a sense of wonderment when you realize the people did this with analog instruments in the classical Islamic ages.”

Muqarnas, Petruccioli says, provides an example of why it’s so dangerous to refer to Islamic architecture as a “style.” The pattern emerged as a solution to a problem rooted in the blending of designs that occurred over centuries as Islamic conquerors encountered Roman forms, particularly during the Ottoman Empire. Muqarnas was an Islamic riff on the squinch, an element that bridged the structural gap between domes, which have a circular base and cubic structures beneath them.

Numerous stories, however, have been inspired more by what the adoption of a certain style says about the evolution of world history than the architectural elements themselves.

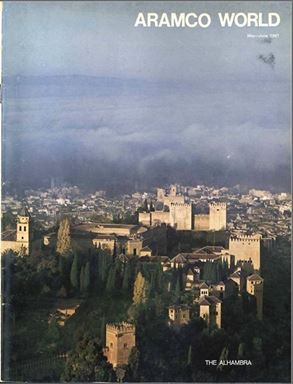

One memorable story for Doughty was the “Alhambras of Latin America (2021),” whose idea came from seeing a building marked “Alhambra” on Google Maps during his stroll through Santiago, Chile.

The iconic Moorish building in Granada, Spain, he thought, must have inspired designs across Latin America, even as the Spanish sought to stamp out the influence of Islam from their colonies in the New World. When he brought the idea to his friend and AramcoWorld contributor Ana Carreño, a Granada-based writer specializing in Arab Mediterranean cultures, he learned that an exhibition focused on “Alhambrismo” was already underway. The two partnered with University of Granada art-history professor Rafael López Guzmán to craft an article.

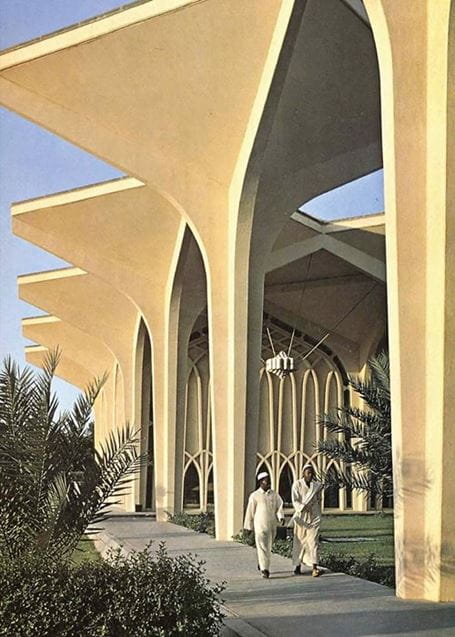

In 1979 innovations in medical care at the King Faisal Specialist Hospital were reflected in a story about its architecture, top left. Even earlier in 1971’s “Building on Tradition,” top center and lower left, photographer B.H. Moody took a non-traditional look at modern architecture with Arab influences in the story “Building on Tradition.” The Alhambra Palace’s architectural influence is undeniable and has been highlighted in AramcoWorld numerous times over the years, including in 1976’s “Architecture in Arabia” and 1967’s “The Alhambra,” bottom left and right.

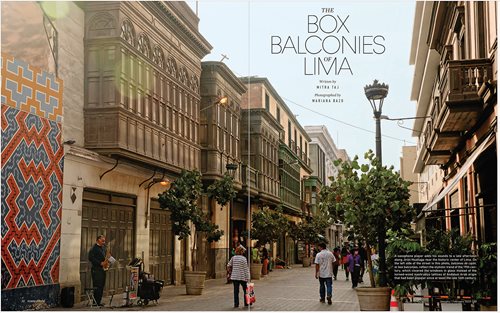

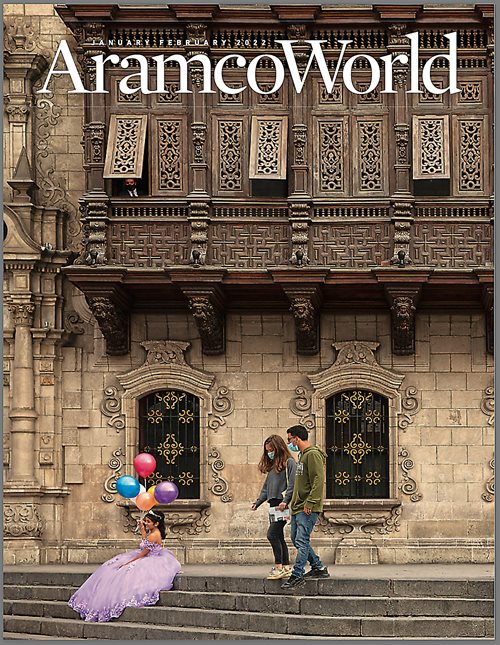

Mitra Taj, a Peru-based journalist, built on that foundation with “The Box Balconies of Lima (2022),” a story that helped her see her adoptive home in a new way.

Taj, an American who had spent time studying in Spain, noticed what looked like traditionally Islamic elements in the older sections of the Peruvian capital, Lima, but, like many locals, had not delved into their origins.

She learned that these balcones de cajón originated in Egypt and were carried to Spain through Muslim conquest, with craftsmen learning them over time. Cantilevered over the narrow streets of old Lima, they presented a way for residents, especially women, to observe street life without being seen, their eyes peering through ornate panels that found inspiration in mashrabiyah, elaborate screens often used for shade and concealment in buildings in the Middle East.

After her article synthesized the views of academic specialists, everyday people began to reach out to her in person and online, some offering their observations of the balconies and others reminiscing about their families’ Arab origins.

“Peruvians are very interested in learning about themselves through the eyes of foreigners,” Taj says. “They were super into it. They didn’t know that there was this sort of history there.”

Taj now sees cultural fusion where she once saw only decoration. While these balconies were likely not built by so-called moriscos, converts to Islam who were expelled from Spain following the Catholic conquest in the 15th century, the persistence of the style as a status symbol pointed to their lasting influence in the colonies.

“Architecturally, downtown Lima looks completely different to me now,” Taj says.

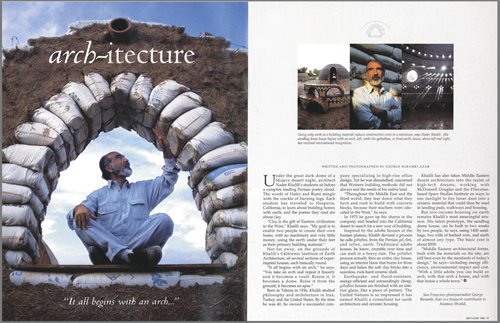

Perhaps more than most, George Azar understands how working on an AramcoWorld story can change perspectives on design, both for the reader and the contributor.

The prominent photojournalist got his start documenting the Lebanese civil war in the 1980s. But in its aftermath, he landed an assignment for AramcoWorld about the restoration of Beirut to its earlier grandeur.

“If you go to the downtown Beirut, it’s absolutely gorgeous; it’s not built in a modern style. It’s built in a classical Lebanese architectural heritage. They rebuilt it to a T,” says Azar.

Walking the streets of Beirut, where he now lives, Azar sometimes experiences a “double exposure,” recalling still images of the war’s devastation even while viewing the fruits of the city’s contemporary renovation.

As his tenure with the magazine grew, it became a font of memorable (and challenging) pieces, giving him time and space to dwell with stories like “Amedi: Citadel of Culture (2019),” where he persisted through days of rain to capture modern life on an ancient mountain fortress in Iraq’s Kurdish region.

Going back even further in time, Azar faced the daunting task of portraying prehistoric architecture in “Jordan: Long Before Petra (2014),” and he observed in “Listening to the Land (2018)” how architect Ammar Khammash counterintuitively focuses on ensuring his designs’ own invisibility.

“The great thing about being a journalist is that you can throw yourself into a story and try to make yourself an expert (with a small e). I was not really someone who knew a lot about architecture, but by its very nature, it’s about design. The best architects are often very good photographers.”

Carreño, the specialist on Mediterranean cultures, found a picture-perfect blend of tradition and modernity in the Louvre Abu Dhabi, whose architecture she profiled for the magazine in 2018’s “A Museum of the World.”

Designed by Jean Nouvel, a French architect, the museum features a massive central dome that incorporates many functional aspects of Eastern design. These include recurring fractals, ventilation and cooling methods inspired by wind towers (barjeel) and irrigation channels (falaj), as well as the concept of a madina, a combination of narrow streets and wide-open plazas.

“To me, like to everybody visiting the museum, the space right under the dome was astonishing,” Carreño says. “When people entered it through a small door, they found an unexpected outbreak of fragments of light and shadow, falling like drops from under a futuristic palm tree in the middle of an oasis surrounded by the waters of the Gulf.”

One of Nouvel’s earlier works, Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris, built in 1989, won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, a prestigious prize recognizing designs that impact life in Islamic societies.

Farrokh Derakhshani, the director, has been associated with the award since 1982, when far fewer resources existed to spread knowledge globally about quality architecture.

“From the very beginning, we understood that this lack of communication, this lack of information, was the problem,” Derakhshani says.

AramcoWorld had a similar mindset, and Derakhshani remembers when John Lawton, a longtime contributor, visited him in Geneva to write about six award-winning projects in “The Changing Present (1987).” An in-depth feature, “Shaking Up Architecture” by Lee Lawrence, followed in 2001.

While it puts shortlisted projects on its own website, the Aga Khan Award disseminates other submissions through a platform at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in the US.

That’s where Petruccioli, the Italian expert, served as the Aga Khan Professor of Design for Islamic Societies in the 1990s.

It’s unclear, he says, where the field of architecture will go in the age of artificial intelligence, but he hopes that resources like AramcoWorld continue to center the way it influences cultural development.

“I cannot predict the end of the story.”

About the Author

J. Trevor Williams

J. Trevor Williams is a global business journalist based in Atlanta where he serves as publisher of the online international news site, Global Atlanta (globalatlanta.com). Follow him on Twitter @jtrevorwilliams.

Ryan Huddle

Ryan Huddle is a Boston-based graphic designer and artist whose work appears regularly in the Boston Globe and other leading publications.

You may also be interested in...

The Bridge of Meanings

History

Arts

There is no truer symbol of Mostar, Bosnia-Herzegovina, than its Old Bridge. The magnificent icon of Balkan Islamic architecture was destroyed during the 1992–’95 war—but not for long. Like the multicultural workforce that produced the original hundreds of years earlier, a broad team of architects, engineers and others came together immediately to plan its reconstruction. This summer marked the 20th anniversary of the bridge’s reopening.

Escher + Alhambra = Infinity

Arts

Visits to Spain in 1922 and 1936 led Dutch artist M.C. Escher to discover the world of designs in Granada’s 13th-century Alhambra palace, where interlocking patterns in tiles and stucco on its walls and ceilings became springboards to ideas that shaped his art for the rest of his life.

Brickwork in the Land of Palms

Arts

Along the northern edge of the Sahara, in the part of Tunisia called Bled el-Djerid—Land of the Palms—the regular pruning of vast date-palm orchards literally fuels a centuries-old brickmaking industry, and local bricklayers have taken the kiln-fired masonry to heights of artistry. Throughout the city of Tozeur and the nearby town of Nefta, bricks set in patterns decorate facades, windows, doors and arches with motifs from desert life, textiles and other traditions. The results not only dance with the changing angles of the sun, but also create just enough shade to help cool the buildings behind them.